What Was New about Nineteenth-Century Shopping

lthough some form of shopping has always been a part of human society, shops, shopping, and the idea of the “shopper” began to be discussed in new ways during the Victorian period as consumerism flourished. Several factors contributed to the growth of consumerism during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Along with the industrial revolution which created the means to produce more goods at cheaper rates, increased efficiency in transportation allowed for these goods to quickly reach different parts of Britain, including goods from the far reaches of the empire.

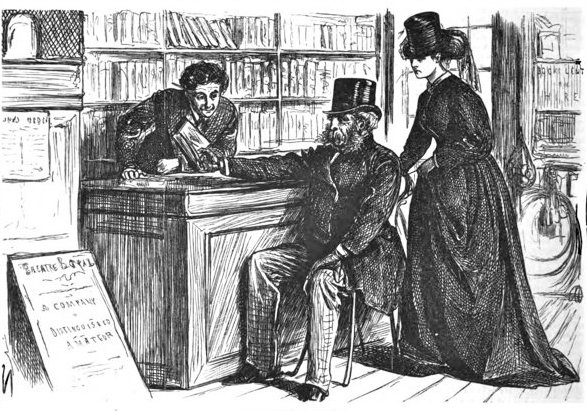

As these two Punch 1867 cartoons remind us, Enlish men and women had long frequented shops for goods as varied as meat from the butcher and books. Left: Where ignorance is bliss by Charles Keene. Right: A Novel Fact by George DuMaurier. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Credit which had always been a part of trade took a new form in Victorian Britain as several stores offered “installment” plans (Shaw 29-32, Graham 2-4). The aspects of retailing that became more pronounced in the Victorian age in included larger stores (department and cooperative), a larger consumer population, innovative techniques in advertising, and window shopping. Victorians showed conflicted positions toward this heightened consumerism: they enjoyed shopping but also expressed their concern over an activity that seemed to celebrate material possessions and their display. Increasingly, gender played a role in discussions about this burgeoning commercialism as popular conceptions in newspapers, magazines and stories cast women as avid shoppers. This image of the female shopper created anxiety and concern from several different perspectives. All of these factors make the act and concept of shopping complicated and intriguing as commercial endeavors shaped cultural norms.

The Eighteenth-Century Roots of Victorian retail practices

Many of the retail practices that became emphasized in the Victorian period had begun earlier in the eighteenth century. John Benson and Laura Ugolini cite Claire Walsh, arguing that cash sales with set prices, window displays, and interior store designs which were “usually associated with the late nineteenth-century department store were already well in evidence a century and more earlier” (2). Jon Stobart, Andrew Han, and Victoria Morgan, point out that shops in the eighteenth century demonstrated “complex retail systems, and the growing sophistication of retail practices” (14). A variety of retail options existed before the advent of the department store and continued to exist during the rise of large-scale retailing. Small shops, for instance, ranged from general goods stores to specialty stores (dressmakers, booksellers, and so on) while itinerant peddlers and street sellers offered more specialized and limited goods or services and frequently carried perishable items (Graham 23-24).

Public transportation in the form of railway trains, ominibuses, and hansom cabs made travel relatively convient and inexpensive for those not wealthy enough to own a coach and horses themselves. Here Punch, which has many cartoons making fun of London taxi men's often rude independence, here satirizes the new invention of the horse-drawn omnibus. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

The popular bazaars of the Victorian period consisted of stalls set up in a building leased to merchants (Graham 29). Although a culture of window display and window shopping had always existed, with the success of the department store and these stores’ window displays, the culture of “looking” became deeply entrenched (Graham 28, 30-31). While the display of retail items in department stores was meant to increase consumer consumption, Susan Lomax argues that during the Edwardian period these displays also demonstrated the store’s credibility and versatility (270). Retailers in general had frequently to establish credibility with respect to the quality of their goods, the fairness of prices, and accuracy of weights and measures.

Cooperative stores, which were large like department stores, actively promoted the idea that they belonged to the people and therefore were trustworthy in respect to goods and prices (Purvis 107-108). Again, while various forms of advertisement had existed before the nineteenth century, the Victorian period took advertising, sales, and bargains to new heights. Retailers advertised through signs by their shops, posters, catalogues, and newspapers (Graham 36-38). Credit offered through installment plans, likewise, revolutionized consumer spending and increased the consumer base as more goods were now affordable to a larger number of people including many from the working class.

Shopping and gender

Shops and clothing went together in many ways during Victoria's reign. Although the wealthiest men and women wore custom-made (or bespoke) clothing created by tailors and seamstresses who came to their homes, prosperous men, as we seen in the 1890 Punch cartoon, went to fashionable tailors for made-to-measure garments. By this time ready made clothing provided members of the middle and working classes the opportunity wearing other than homemade clothing. Several aspects of the Industrial Revolution made possible the scene we see on the left: the textile industry created the necessary fabrics for women's dresses canals and railroads made them available in many cities, newspapers and magazines spread the latest fashions, and the invention of both the sewing machine and paper patterns enabled women to sew their own clothing in fashionable styles. Formatting and perspective correction by — George P. Landow. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

The middle and upper classes increasingly accepted the idea of separate spheres for men and women in the Victorian period, with men of the middle and upper classes moving in the public sphere of work while women maintained the home as a place of moral sanctuary. Smaller retail establishments mixed the idea of public and private as shopkeepers often used the same building for their shop and home. With the increase in consumerism, retail establishments created additional blurring of the lines between public and private as more and more wealthy women ventured into public space to shop. Risks for any shopper, male or female, existed in the form of thieves and pickpockets and dishonest shopkeepers who might sell adulterated goods or use improper weights and measures. With female shoppers, however, concerns arose over sexual behavior; women might be mistaken as prostitutes or face different levels of sexual assault. Upper-class and middle-class women, who were also perceived as having too much time on their hands, were consequently thought to be wasting money on frivolous and materialistic things when they shopped (Graham 6-7, Steinbach 111). Yet the moral responsibility that fell on women in maintaining the home could also carry into their public ventures for the home; conduct books advised that shopping for the home carried importance and that women needed to demonstrate care in spending money and evaluating products (Graham 27).

Interestingly, many women were involved in trade by either running their own businesses or working as shop assistants. In separate studies, Margaret Hunt, Nicola Phillips, and Hannah Barker observe that women owned and ran at least ten percent of all retail businesses and that, in all likelihood, this number could be higher. Women shopkeepers further blurred the lines of separate spheres and contradicted domestic ideology. Women who worked in retail establishments as shop assistants and not owners could still find a measure of independence even while facing the risk sexual assaults from customers, fellow assistants, and storeowners. Working in retail required hard work that was less strenuous than factory labor or domestic service, and many women preferred jobs as shop assistants.

Shopping in Victorian literature

Victorian literature has numerous depictions of shops and shoppers. Children’s literature of the period, for instance, presents shops and shopping as integral features of life and adventure. In Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass (1871), for example, Alice finds herself abruptly standing in a shop run by a ewe. The shop has many familiar features such as fully stocked shelves containing a variety of goods, and Alice, like a good Victorian, chooses to look before she buys. Alice’s shopping experience, however, proves less than satisfying; every time she turns to look at a shelf, the goods on it mysteriously vanish. Shopping becomes part of the “backwards” life of the looking glass land, insubstantial and chaotic – another of Carroll’s subtle critiques of contemporary life. In The Story of the Amulet (1906), Edith Nesbit’s intrepid child protagonists, on the other hand, wander through various small stores and stalls in London and seem to have a very ordinary day before they stumble on their magical friend the Psammead who in turns leads them to a sacred Egyptian charm. Eitan Bar-Yosef compellingly argues that Nesbit introduces an element of anti-Semitism throughout the novel, one such instance being in her portrayal of the shopkeeper who sells the charm. As Carroll and Nesbit demonstrate, shopping – a common, essential activity for the Victorians – can also represent social and political anxieties.

Bibliography

Bar-Yosef, Eitan. “E. Nesbit and the Fantasy of Reverse Colonization: How Many Miles to Modern Babylon?” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920 46.1 (2003): 5-28. Project Muse. Web. 10 August 2013.

Barker, Hannah. “Women and Work.” Women’s History: Britain, 1700-1850: An Introduction. Ed. Hannah Barker and Elaine Chalus. London and NY: Routledge, 2005. Print.

Benson, John and Laura Ugolini, ed. A Nation of Shopkeepers: Five Centuries of British Retailing. London and NY: I. B. Tauris, 2003. Print.

Emery, Joy Spanabel. A History of the Paper Pattern Industry: The home Dressmaking Fashion Revolution. London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Graham, Kelley. “Gone to the Shops”: Shopping in Victorian England. Westport, CT and London: Praeger, 2008. Print.

Hunt, Margaret. The Middling Sort: Commerce, Gender, and the Family in England, 1680-1780. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996. Print.

Lomax, Susan. “The View from the Shop: Window Display, the Shopper and the Formulation Theory.” Cultures of Selling: Perspectives on Consumption and Society Since 1700. Ed. John Benson and Laura Ugolini. Aldershot and Burlington: Ashgate, 2006. Print.

Phillips, Nicola. Women in Business, 1700-1850. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2006. Print.

Purvis, Martin. The Evolution of Retail Systems, c. 1800-1914. Ed. John Benson and Gareth Shaw. Leicester, London, NY: Leicester University Press, 1992:107-134.

Shaw, Gareth. “The European Scene: Britain and Germany.” IN The Evolution of Retail Systems, c. 1800-1914. Ed. John Benson and Gareth Shaw. Leicester, London, NY: Leicester University Press, 1992: 17-34.

Steinbach, Susie. Understanding the Victorians: Politics, Culture and Society in Nineteenth-Century Britain. London, NY: Routledge, 2012. Print.

Stobart Jon, Andrew Hann and Victoria Morgan. Spaces of Consumption: Leisure and Shopping in the English Town, c. 1680-1830. London, NY: Routledge, 2007. Print.

Last modified 19 August 2014