"Many a young man starts in life with a natural gift for exaggeration which, if nurtured in congenial and sympathetic surroundings, or by imitation of the best models, might grow into something really great and wonderful."

[Introduction] — [Act One] — [Act Two] — [Act Three] — [Act Four] — [Act Five]

Introduction

Wilde, like fellow Irishman and friend Yeats, was a brilliant oral storyteller, a temporally displaced bard. When he fell from grace during scandal in later life, he earned many a meal-and arranged many a loan — after ensuring an after dinner audience's affection with a good tale. It is largely from this practice that he initially achieved notoriety, and from jotting down the essence of his speech that he made his living- for Wilde, who often found the act of writing disagreeable (yet never the act of talking) believed that writing was a necessary way of venting immense intellectual energy, but for him not an end in itself. Given that he identified himself always as a speaker-first as a bard and then, as he grew older, as Platonic guru to young Oxfordonians- it is unsurprising that he made a drama of his life. Often, as Philippe Jullian reports, he knew that his greatest role was that of "the artist triumphing over the brute" (Oscar Wilde, p.318), and in this sense certainly his literature, rather than being his definitive artistic statement, became a backdrop for his real art-life.

As the painter is drawn to warm and cool tints, Wilde was fascinated by the dichotomy between the good and evil components of life. Like an actor, he is more taken with beauty than content-asserting that if there was an afterlife that he should like to return as a flower, utterly without soul but entirely beautiful. In statements throughout his life-often paradoxical and of which Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young (1894) is quite representative-he apparently propones beauty over soul. In a letter to his mother he cries: "I'm unable to write a line or a sentence so long as I'm not in complete possession of myself. I should like very submissively to follow nature-which is within myself and must be true." (Delay, Andre Gide, p.396) Yet he also believed, as reported by Jonathan Dollimore in his analysis of Dorian Gray, that "anyone attempting to be natural is posing." (Sexual Dissidence, p.10) The distinction between the two uses of "natural" explains a good deal about why more conservative peers misunderstood Wilde. He favored nature when it was construed as an internal individualistic impulse (think Whitman), but not when it was considered as it was by most people: as society's norm. Similarly, when he suggests that beauty is the greatest good and in so doing diminishes the role of the soul, he does so not out of shallowness, but out of a half-facetious, half-earnest pursuit of that which is more genuine, less socially constructed (and therefore less hypocritical).

This search for uncorrupted nature led Wilde to a ferocious individualism, ironically attained by means that in the nineteenth century were considered criminal: sexual deviancy. Dollimore relates Wilde's homosexuality to the search for self-identity, suggesting that he creates a natural self only by casting down "a Protestant ethic and high bourgeois moral rigor and repression that generated a kind of conformity which Wilde scorned." (p.3) Wilde brought about this internal upheaval, or recreation as Dollimore puts it, in many young disciples (significantly Gide, who is most vocal about reporting the chaos it threw into his life). This practice, somewhat of a game to Wilde, calls to mind The Picture of Dorian Gray, in which young Dorian is seduced and corrupted by the older Lord Henry, who attempts to both free the beautiful boy from convention and entertain himself.

This parallel between life and literature is not the least reason to believe that Dorian Gray provides insight into Wilde's life when read as an autobiography. Mutlu Konuk Blasing writes in The Art of Life that "autobiographical writing necessarily involves a splitting or doubling of the self. In the act of writing about oneself, the author becomes narrator and hero, observer and observed, subject and object, and the two selves are like mirror images of each other." (p.27) This is clearly read in Dorian Gray, where the disjunction between self-image and public image are captured in superficial allure of Dorian's face and the repellant, withering soul that the painting represents. It has been suggested that in most of Wilde's works-in which the same cast of characters is paraded before the reader repeatedly-most characters are an expression of the author in different moods. In Dorian Gray, Lord Henry represents the perverted, elder Wilde, and the gorgeous but soulless Dorian (distinct from his concrete conscience, stored in the painting) is that part of Wilde which has been itself corrupted. The text becomes Wilde's way of reintegrating the his "self", in the same manner, Blasing suggests, as Whitman's "Song of Myself", in which the poet "unites the self by defining consciousness-the self as subject-as literal self-consciousness on consciousness of the self as object." (p.27) In breaking up personality into at least three sections-innocence, soul, and corruption-Wilde tries to make sense of each, and test different ways of fitting them together. Watching him try to do this is an excellent study of how he fit together the conflicting units that composed his personality.

Only when Dorian attempts to live without a soul at all is he destroyed, during an inversion in which the painting-which has served as his confessional-is broken and the floodgates released to destroy the unrepentant. Only in first understanding a little of Wilde the actor, and of the complex disparities between his roles as loving tutor and corrupting presence, author and oral storyteller, and supporter of individual naturalism but foe of what was natural in the eyes of society can he be approached. The next section will explore other disparities in his life: the predicament of an Irishman in England, and the sources of discrepancy between Wilde's fierce, anarchic, individualism and his paradoxical obsession with social status.

Act One

William Wide and Lady Jane Francesca Wilde, Oscar's parents, were Dublin celebrities. William Wilde was a prominent eyatione and ear surgeon-indeed he is often credited with asserting the branch of medicine as a science. In addition to his successful practice, he wrote numerous volumes on his particular branch of medicine-several of which became standard universal textbooks for succeeding decades-as well as travel guides, histories, and poems. He was a talented conversationalist, and led a busy and active social life in the midst of Dublin's elite. Lady Wilde was a noteworthy agitator for Irish Independence (the "Green Movement"), revolutionary poetess, critic, and early advocate of women's liberation. She was a genius (self-proclaimed, also however so testified by acquaintances), and a witty talker, and Oscar Wilde would assume most of her characteristics. He later exhibited her preference for rising in the afternoon, would affect an aversion to the sun, harbor a passion for classical verse, and show skill in entertaining the literati by exaggerating truth and myth alike to produce remarkable and endless stories. Yeats said: "When one listens to [Lady Wilde] and remembers that Sir William Wilde was in his day a famous raconteur, one finds it in no way wonderful that Oscar Wilde should be the most finished talker of our time." (Davis Coakley, Oscar Wilde: The Importance of Being Irish, p.75) The foundations for Wilde's belief that his true art was life are found in one of his mother's books in which she rather dramatically suggests that "The queen regnant of a literary circle must at length become an actress there." (Men, Women, and Books, p.144) The talented and eccentric Lady Wilde, who called herself "Speranza" in order to associate herself with Dante Alighieri and the Italian aristocracy, from which she believed she was descended, also instilled in Wilde a love of paradox. Both admired Disraeli, and his approach of reversing popular axioms-Davis Coakley gives the example, partners to which would appear in so many of Oscar Wilde's works and conversations: "He was born of poor but dishonest parents."

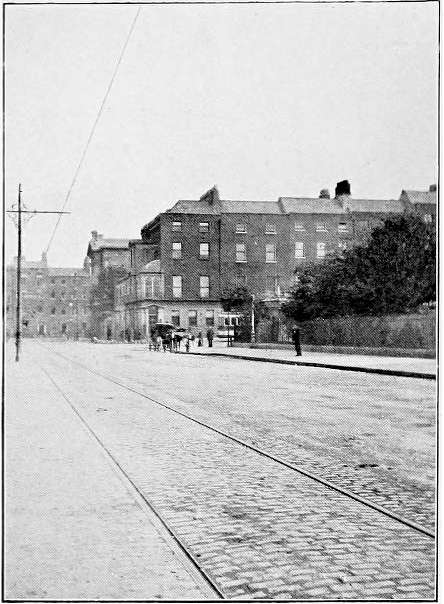

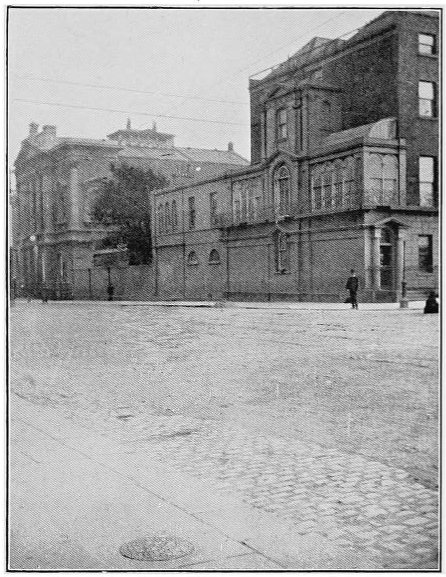

Left to right: (a) Merrion Square, Dublin, where Oscar Wilde's youth was spent. (b) House in Merrion Square, Dublin, where Oscar Wilde lived as a boy. [Click on these images to enlarge them and to obtain additional information.]

The sixteenth of October, 1854, Oscar Wilde was born into a most stimulating environment. The family, which included two year old brother Willie (Willie became a journalist in London), lived on the North Side of Merrion Square-the right part of the right neighborhood for members of those professions "fit for gentlemen" who aspired to the aristocracy. Speranza held a weekly Salon in a candle-lit (on the sunniest of afternoons) front room, which attracted the best and brightest of Dublin's artists, writers, scientists, and miscellaneous intellectuals. Oscar Wilde, at the youngest of ages, was encouraged by both parents to sit among such visitors as, perhaps, John Ruskin-later an influential teacher and friend at Oxford-and fetch books for his father, or amuse adults with his stories.

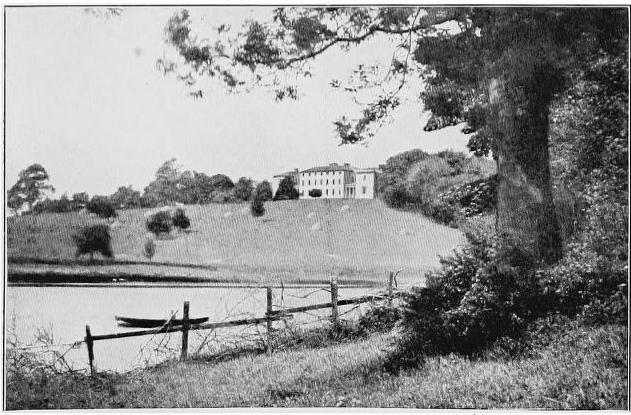

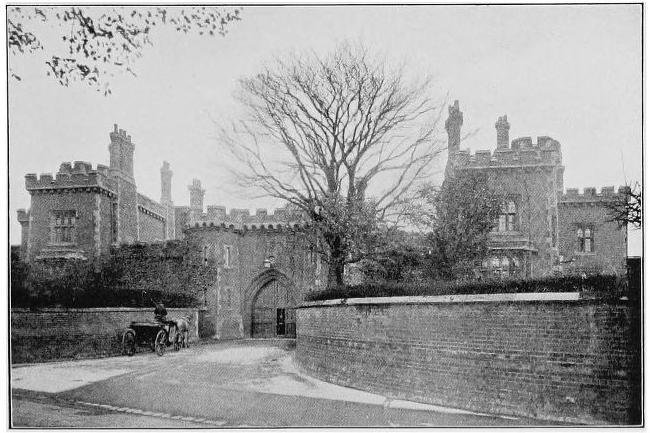

Portora Royal School, Ireland, where Oscar Wilde was educated. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

After nine years, Wilde was sent to the Portora Royal School, which some years later also cultivated Samuel Beckett, and which offered an education steeped in the classics. The institution was a favorite of Irish professionals, and the degree to which it embodied the aspirations of the rising upper middle class is noted in the hope of its headmaster-a liberal and academically celebrated Trinity College graduate named William Steele-whose ambition it was "to develop a school that would not only be the best in Ireland, but which could compete with the best schools in England." (Coakley, p.79) Around the same time, William Wilde acquired a pastoral estate around Cong, which according to Coakley "moved his family from the ranks of 'loyal professional people' into the ranks of 'country gentry', with the attendant social advantages." (p.94)

Clearly, the enlightenment of Wilde's family did not put it above the Victorian middle class trap of needing to live up to the aristocracy, an apparently universal middle class obsession. The Wildes strove to preserve their children from the rest of the middle class, and Wilde observed that he "grew up surrounded by this poverty, but he was protected from its harsh realities as he played in the garden of Merrion Square." (Coakley, p.110) Both Oscar and his mother are bluntly described in many sources, as "snobs". Although Wilde exhibited a deep sense of compassion for the victims of society (so much compassion, in fact, that he became one during many periods of his life), it remains in interesting disjunction in his life that although he championed individuality, he was ever guilty of obsessing with "getting on". Perhaps this can be attributed, like so much else, to his full-time acting role, which allowed him to not practiced what he preached, and even to not really care about whether he was a hypocrite or not. Or, perhaps it can be linked to the hardship that the family knew when William Wilde fell from grace as one of Dublin's most prominent men, financially and (to a degree) socially ruined by scandal, illness, and mental breakdown.

If Wilde's family strove to distinguish themselves in their present, they also worked to do so by rejuvenating their past, discovering links to Irish myth and heroism in a way that was very influential for Wilde. Philippe Jullian writes:

In this oppressed country intellectuals took refuge in delving into the distant past. To be able to claim former grandeur, the erudite exhumed that civilization which between the fifth and eighth centuries produced the marvelous illuminated manuscripts and sculptured crosses covered with tracery whose influence could be seen reappearing at the end of the nineteenth century in Art Nouveau. They wrote wild and poetic legends (Oscar Wilde, p.8)

Socially favored were those who could construct the most captivating stories about illustrious history, and many stories wove superstition into the formula. Wilde and his mother were very superstitious people, and Wilde claimed to have been visited by both his mother and his wife on the eve of their deaths, although on both occasions he was separated by many miles (and, in the case of Speranza's death, which occurred when Wilde was incarcerated, by formidable walls). This immersion in the supernatural had an impact on Wilde's stories, particularly Dorian Gray and Lord Arthur Savile's Crime, in which the protagonist is driven to absurd distraction by the prediction of a white-knuckled fortune- teller. He was also influenced in this stage by Speranza's memory of her uncle Charles Maturin, an early author in the horror-fantasy genre-and a source of great pride for the family-and by Bram Stoker (author of Dracula), who was a frequent guest at Merrion Square.

Irish superstition and myth not only set Wilde apart in England by fueling excellent stories, but also by leaving its mark on his dress (he always wore a scarab ring on each little finger), and in his actions (he advised friends about avoiding the "Evil Eye"). This behavior must have been-as Wilde is certain to have considered-incongruent with the English social norm, and he probably considered it to be a prop at Oxford and after. A prop which-like Lord Byron's pet bear and human skull flagon-affirmed his social status (and catered to his elitism) since, Speranza was convinced, eccentricity went hand in hand with genius. Thus we read Wilde using displaying calculated eccentric individuality in statements like "Ambition is the last refuge failure" and "Faithfulness is to the emotional life what consistency is to the life of the intellect-simply a confession of failure," fully intending that such statements should distinguish him as one whose brilliance gave him the luxury to be complacent. Cultivation of mystique worked, and through a combination of strange behavior, entertaining storytelling, and effortless academic prowess-all of which attributes were somewhat gained by his uniqueness as an Irishman steeped in domestic myth and tradition-Wilde was a star before he had really published anything at all.

Act Two

Wilde won a spot at Trinity College Dublin in 1871, departing Portora Royal School with his name engraved in guilt letters on the honors board, and having easily won an important prize in Greek-much to the surprise of all who had believed him to be brilliant but slothful. At Trinity, Wilde won all sorts of prizes for his scholarship-most significantly the coveted Berkely Gold Medal, which he pawned several times in later life to support himself. Although he had little to do with most of the College's social activities and clubs, he did contribute to the Hellenistic journal and befriended John Pentland Mahaffey, Trinity College's leading Greek scholar, a source of his interest in the "Greek ideal". Here he also began study of aesthetic theory, reading Morris, Ruskin, and Rossetti, and learning about other Pre-Raphaelites.

Magdalen College, Oxford

It must have been a jarring change to be transferred from the home of a revolutionary mother to the seat of English Imperial Education, but Wilde matriculated in Magdalen College, Oxford on scholarship, in 1874. Here, his already discussed preference for the past-not uncommon for men of the era-was sustained and furthered by his growing friendship with two great men, John Ruskin and Walter Pater. Ruskin remained in the Middle Ages, and Walter Pater justified a love of the Renaissance by arguing that, as far as he was concerned, the qualities and achievements that distinguished the former period were continued in his. The two disagreeing critics tugged Wilde in opposite directions. Wilde ever a man-in his mind at least-of eighteenth century aristocracy, he had to reach an accord between Ruskin's moral medievalism and Pater's Renaissance aesthetic, which placed beauty and subtlety highest (the latter eventually triumphed in Wilde's soul). At least both permitted unabashed, elitist yearning for the past-always the aristocracy was the model. At Oxford, Wilde was also introduced to the joys of combining Mahaffey's Greek ideal with homosexuality-the University's young men, according to several biographers, expressed delight in each other's beauty and brilliance, and Wilde later wrote of the pleasures of strolling through the grounds observing his pleasant peers. Perhaps it was these years of tranquil pleasure-for him, a Hellenistic ideal of joining love and intellectual growth-that he was trying to recapture when he established himself in middle age as Plato to young Oxford beauties. Of course in later life this harmful and unconventional practice ruined him.

Act Three

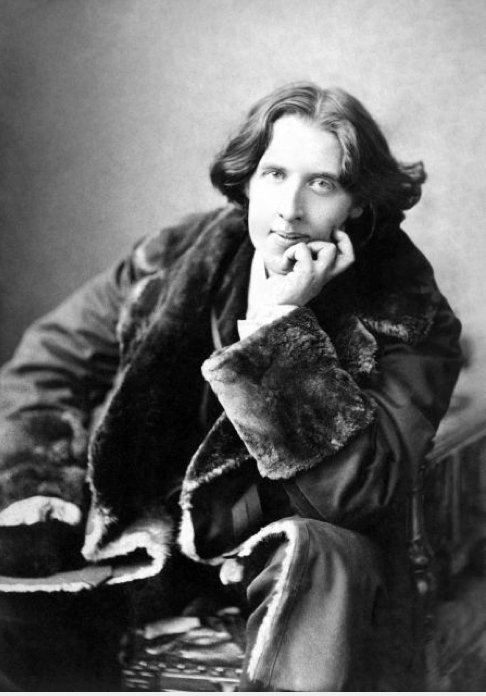

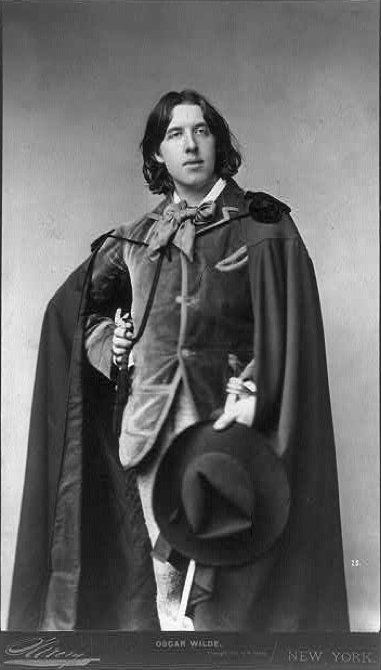

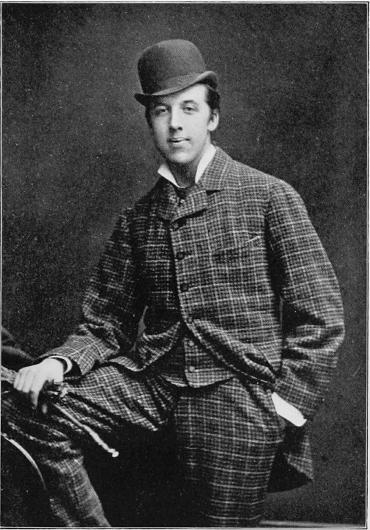

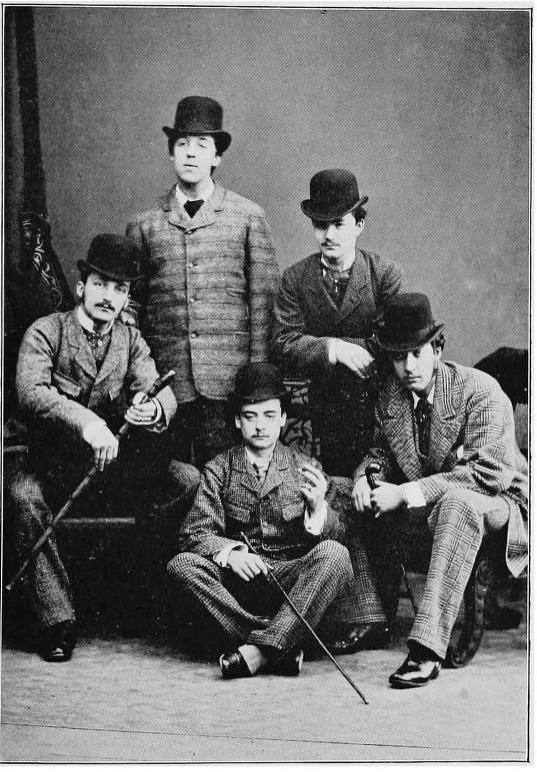

Left: Oscar Wilde (standing up) with fellow undergraduates (1878). Right: Oscar Wilde as an undergraduate (1876). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Just before he left Oxford, Wilde won the Newdigate Prize for a poem, "Ravenna". Ruskin had obtained this some years before, and it was considered by many to be an indication of certain success. Indeed, Wilde was the favored pupil of the best. Walter sought Wilde's company, and the student spent several months editing Mahaffey's books and touring Greece with him. Both of these scholars fought to preserve Wilde from Roman Catholicism during this period. Wilde-like many of his peers in Oxford and in the Aesthetic movement-was drawn to the religion because of the ritual and ceremony, opulence and imagery, because of the institution's adroit use of art to illustrate beauty and morality, and because of the complex sexual drama played out in the church. David Hunter Blair arranged a private audience with the Pope during his visit to Rome, and Wilde was sufficiently moved by the Pope's blessing and expression of hope that he would be converted that he rushed off to write sonnets about the experience. Many of his religious poems of this period were well received at British monasteries. But despite his interest in Catholicism, Wilde preferred to not attach himself to one belief system-particularly after Mahaffy "Hellenized" him (in the words of Blair) on the tour of Greece. (Coakley, p.170)

In addition to the intellectual energy Wilde was expending at the time, he endured some emotional stress as his father died and left the family with little money and greater debts. At the time he finished Oxford, his mother moved to London in an attempt to clear the slate, and established her Salon in Chelsea, quite a bohemian district of the city, and her parlor became a gathering place of great minds once more. Too add too his problems, he had recently been disappointed in love by Florence Balcombe-described by George du Maurier as one of the three most beautiful Victorian women-when she broke off a loose affair without telling him and married Bram Stoker. Wilde was, however, to know greater distress, and he indicated that he enjoyed the drama of his role as the jilted lover.

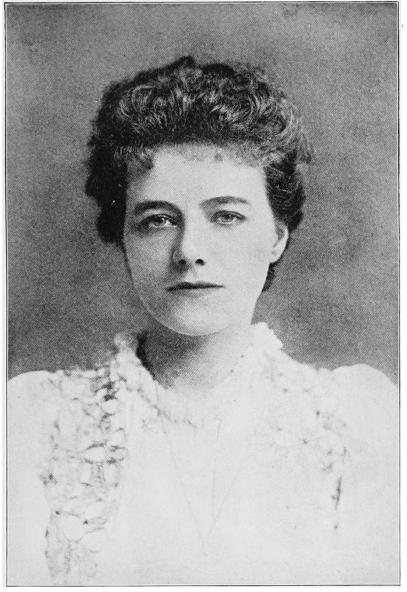

Constance Lloyd.. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Moving into Chelsea he found activity that matched all that he had known. Jullian describes how he found the Modernists divided into the older Pre-Raphaelites of Ruskin and the more amusing followers of Whistler, the latter of which attracted him far more at the time. (p.79) In 1882 Wilde, again short of funds, embarked on a lecture tour of the United States. At each stop, he preached the "Cult of the Artificial" which rejected the social conception of the natural for the reasons discussed in the Introduction. Fully playing the role of the Aesthete, he dressed the dandy to a tee. [He did not, however, reply to a Customs officer when asked what he had to declare: "I have nothing to declare except my genius." — that, alas, is apocryphal.] He appears to have valued the stories that he gained from his journey more than the experience itself, and his last statement to an American reporter, "They say that when good Americans die they go to Paris. I would add that when bad Americans die, they stay in America," seems to sum up his feelings. He spent the next couple of years in Britain and France, championing 'Art Nouveau'-essentially the Aesthetic, art for art's sake movement-before violating all of his bachelor's principles in an attempt to "settle down" and marry the attractive, love-struck, Constance Lloyd.

The marriage, in late May 1884, represented all that was to go badly with the union as a dumbfounded and unappreciative woman of quite mediocre intelligence was thrust into the resplendent world of the Aesthete Prince. Coerced by her groom to wear a cream gown with high collars and an Eastern veil, Constance witnessed a beautiful but unconventional wedding. Men dressed in matching "decadent" shades, bridesmaids wore Surah silk, "the color of a ripe gooseberry" with yellow sashes, and guests like Whistler and Sargent were in attendance. Following the wedding they moved into the marvelous 34 Tite Street, decorated with advice from Whistler, in a style that predicted the Edwardian taste. Visitors would describe the shy and doll-like bride hanging on each of Wilde's words, speaking little, an attractive prop more than a person.

Why Wilde, like many in his period, elected to attach himself to someone who could admire but not appreciate him, who was more child than adult, is a fascinating question. The first edition of Mahaffy's book about Social Life in Greece from Homer to Menander proposes that Greek men preferred beautiful Greek boys because women were not sufficiently cultivated to provide interesting company. (1874, Coakley reports that the passage was expunged from subsequent editions because it the author had received too much criticism for his defense of Classical homosexuality) Could it be that brilliant men married average women as an extension of their scholarship that led them to see the wife as the child bearer and only other men as worthwhile company? This chauvinist possibility is unlikely. Between the power issues raised by his latter play, Salome, and his close friendship with a woman he called "The Sphinx" (because of her depth and mystery), and because of his great regard for his clever mother, it is clear that Wilde's conception of women was too deep for him to fool himself into living that closely with the Greeks. Another possibility is that, as I believe was the case with John Ruskin, he saw the "little girl" figure as a link to innocence. Perhaps in his quest for a kind of naturalness that was uncorrupted by society, he sought along the way a mannequin so pure, so blank, that he might craft her into the ideal woman. Or perhaps Wilde just grew tired for a moment and decided to settle down with the first available love. At any rate, the two had a quite horrible marriage and Wilde largely ignored his two children.

This period of short-lived domestication saw Wilde become editor for Woman's World magazine, and for the middle of the decade he was less productive creatively. By 1889 he was bored with the tame life, had let the editorship of Woman's World slip away along with the substance of his marriage, and was publishing provocative essays largely dealing with the self-explanatory Art for Art's Sake. His book, Intentions, contained essays called The Decay of Lying; The Critic as Artist; Pen, Pencil and Poison; and The Truth of Masks. They were written in the form of "dialogues" between a new Plato and his young disciples, an intellectual exercise that the author would soon begin to live out. The next five or seven years saw the height of his fame as he published and produced witty and scandalous plays like The Importance of Being Earnest, An Ideal Husband, Lady Windermere's Fan, and A Woman of No Importance. Additionally he published perhaps his best work-but one that led his wife to complain that people would no longer talk to them after having read it-The Picture of Dorian Gray, which I earlier argued was his autobiography.

Act Four

Unfortunately, popular acclaim made him too cocky, and he became increasingly aboveboard about his interest in homosexuality and Platonism. He met the charming but temperamental Lord Alfred Douglas ("Bosie"), then an undergraduate at Oxford, and began a very close relationship with him. This continued for years, causing Wilde to neglect family and Douglas to forget his studies, until Bosie's father, Lord Queensberry—inventor of the boxing regulations and apparently a bit of a lunatic—began to stalk and harass our hero in search of evidence with which he could persecute him. In 1895 Wilde sued him for libel after receiving an accusatory note, and Queensberry began to turn London inside out in a search for evidence to support his claim. A number of Wilde's passionate letters to Bosie were already circulating, and they were used with several of Wilde's own works — and a list of male child prostitutes that he kept company with — to convict the poet. Why Wilde began a libel suit that he was bound to loose seems inexplicable. One suggestion is that the idea of a glorious fight against English justice was a remnant of his Irish upbringing with a revolutionary mother (Jullian, p.316). Following this disaster, Wilde was convicted on sodomy charges with the same evidence.

Reading Gaol. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

After the trial, he was given several opportunities to flee the country, but did not. Probably this was due to the high esteem in which he held Speranza who told him that if he remained, she should stand behind him, but that if he left she would disown him. He remained in prison until 1898, and the humiliation led him to produce De Profundis, which was an Apologia in the form of a bitter letter to Bosie. He also drew from his experience to produce The Ballad of Reading Gaol and several articles against the poor conditions in British prisons, one of which contributed to the passing of a law to prevent the imprisonment of children.

Act Five

After Wilde's release he at last escaped to France, where he was rejected by most of the people with whom he had consorted and who had admired him in better days. Aubrey Beardsley, who had illustrated the published version of Salome (and who was dying at an early age from consumption), would cross streets to avoid him. Old mentors like Mahaffy, if asked about Wilde, would murmur the brutal sentence, "We no longer speak of Wilde." Constance Wilde would send him an allowance, but would not see him (which he did not mind) or allow him to visit his children (which he did mind). A brief romantic reunion with Bosie cut off that little amount of income also, and Wilde waited three years to die. When death came, it came in a lonely Paris hotel room to a man stripped of all arrogance and beauty-a man not too unlike the withered cadaver that remains after the painting is violated in Dorian Gray.

Further Reading

Coakley, Davis.Oscar Wilde: The Importance of Being Irish.Dublin: Town House, 1995.

Dollimore, Jonathan.Sexual Dissidence. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995.

Ellman, Richard.Oscar Wilde. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1988.

Jullian, Philipe. Oscar Wilde. New York: The Viking Press, 1969.

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. USA: Barnes and Noble, 1995.

Last modified 8 June 2007