n April 1887, Oscar Wilde accepted the position as editor of The Lady’s World, a high-end, illustrated monthly magazine produced by Cassell and Company. Wilde expressed the opinion to poet Harriet Hamilton King that The Lady’s World was ‘a very vulgar, trivial, and stupid production’ (Complete letters, 332) and, in the face of strong opposition from Cassells, he renamed the magazine The Woman’s World. In a letter to Thomas Wemyss Reid, General Manager of Cassells, he undertook to transform the magazine into ‘the recognised organ for the expression of women’s opinions on all subjects of literature, art, and modern life’ (Complete letters, 297). He vowed that, under his editorship, The Woman’s World would: ‘take a wider range, as well as a high standpoint, and deal not merely with what women wear, but with what they think, and what they feel’ (297).

A reproduction of the magazine cover, the title-page with Wilde's name, and the binding of The Woman's World annual volume. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Wilde’s Motivation

It is often assumed that Wilde took on this editorial role simply to secure access to a regular income. Certainly, as a married man of thirty-two with a young family to provide for and exquisite tastes to gratify, he found it impossible to fund the lifestyle he desired out of his unreliable earnings as a freelance reviewer and, by then, occasional lecturer. Although his wife Constance brought a modest allowance to the household, by 1887 the couple’s resources were falling distressingly short of their outgoings and they were looking for tenants for their lovely Tite Street home. Yet, although the weekly salary of six pounds was very welcome, it does not account entirely for Wilde’s motivation in agreeing to accept Cassell’s offer.

As a committed individualist, Wilde believed that women should be allowed far more autonomy than they were afforded by patriarchal Victorian society. He also shared his mother’s opposition to gendered writing, resistance she had expressed in forthright terms when, as a young woman, she had been offered control of the ‘woman’s page’ of The Nation newspaper. Echoing his mother’s distain, Wilde quipped in a letter to Wemyss Reid: ‘artists have sex but art has none’ (Complete letters, 298).

As a regular contributor to several popular periodicals, Wilde must have realised how badly served intelligent, ambitious women were by the plethora of new magazines claiming to represent their interests. In response, he used The Woman’s World to point out the more absurd aspects of gender discrimination, and to facilitate debate on the contentious issues faced by women who were attempting to enter the public sphere. He also offered a platform to emerging women writers who displayed a style that could be considered more edgy than that adopted by their peers.

Wilde’s zeal for his new role was palpable: ‘I am resolved to throw myself into this thing,’ he told Wemyss Reid, ‘I grow very enthusiastic over our scheme’ (Complete letters, 299-300). In ‘Oscar Wilde as Editor’, an article he wrote for Harper's Weekly in 1913, Arthur Fish, the young man appointed by Cassell and Company as Wilde's sub-edito, insisted that the ‘keynote’ of The Woman’s World under Wilde’s editorship was no less than ‘the right of woman to equality of treatment with man’ (Fish, 18). Fish also testified that several of the articles on ‘women’s work and their position in politics were far in advance of the thought of the day’ (18).

Contributors

With the help of his well-connected friend Lady Mary Jeune, Wilde compiled a list of potential contributors, among them prominent social activists, literary luminaries and society women, including two princesses. Fish called them ‘a brilliant company of contributors which included the leaders of feminine thought and influence in every branch of work’ (18). Since Wilde had told Wemyss Reid that he intended to make The Woman’s World ‘a magazine that men could read with pleasure, and consider it a privilege to contribute to’ (Complete letters, 297), he also invited several men to submit articles.

The first issue of The Woman’s World appeared in November 1887. A fresh cover design featured Wilde’s name prominently with key contributors listed below. In a significant departure from convention, each article was attributed to its author by name. Wilde also increased the page count from thirty-six to forty-eight, and relegated fashion to the back while promoting literature, art, travel and social studies. Gone entirely were ‘Fashionable Marriages’, ‘Society Pleasures’, ‘Pastimes for Ladies’ and ‘Five o’clock Tea’. In his ‘Literary and Other Notes’, Wilde demonstrated unequivocal support for the greater participation of women in public life. He campaigned for them to be granted access to education and the professions, and argued that the ‘cultivation of separate sorts of virtues and separate ideals of duty in men and women has led to the whole social fabric being weaker and unhealthier than it need be’ (WW, 2 (1897): 390).

The editorial direction Wilde intended to take was signalled by the inclusion in the very first issue of ‘The Position of Women’, a lengthy article from Eveline, Countess of Portsmouth. She welcomed amendments to marriage law designed to reform an institution that, in her view, ‘might and did very often represent to a wife a hopeless and bitter slavery’ (WW, I, 8). In ‘The Fallacy of the Superiority of Man’, published the following month, Laura McLaren, founder of the Liberal Women's Suffrage Union, asked: ‘If women are inferior in any point, let the world hear the evidence on which they are to be condemned’ (WW, I, 54).

A New Slant on Fashion

Left: Scene from “The Faithful Shepherdess” — the frontispiece to the 1888 Woman's World. Right: Orlando. Both plates are illustrations to “The Woodland Gods” by Janey Sevilla Campbell. These images and those below coem from the Internet Archive version of a volume in the Stanford University Library. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Although fashion remained a key feature, a conventional round-up of the season’s trends was supplemented with articles on cross-dressing, aesthetic design and rational dress. On the first page of his first edition, Oscar published ‘The Woodland Gods’ a review by the aristocratic Janey Sevilla Campbell, more commonly known as Lady Archibald Campbell, of three cross-dressing dramas staged by her Pastoral Players at her home, Coombe House in Surrey. This article was illustrated with images of Janey dressed as a young man to play Orlando in As You Like It and embracing a woman as Perigot in Fletcher’s The Faithful Shepherdess.

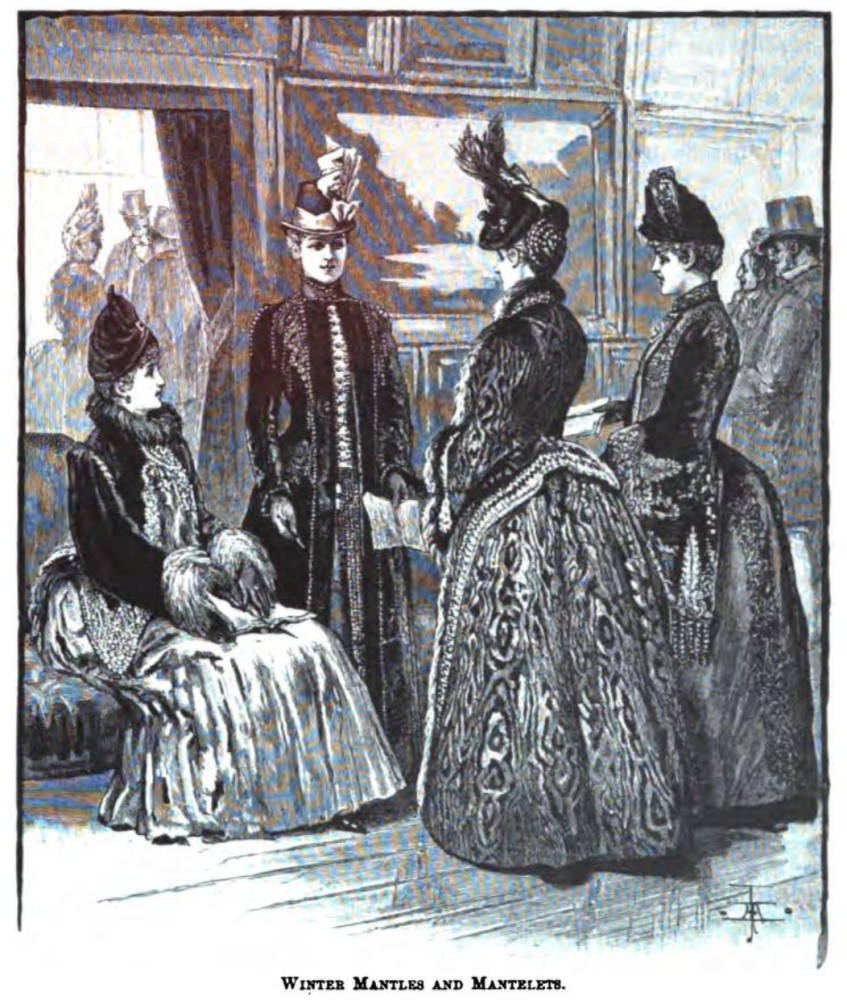

Examples of the large number of conventional illustrations of current fashion, which appeared every month — these from Mrs. Johnstone’s “November fashions.” Left: Morning Costume and Frock with Velvet Yoke — Right: Winter Mantles and Mantlets. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In ‘The Pictures of Sappho’, in April 1888, classical scholar Jane Ellen Harrison challenged several gender-based conventions while, in June 1889, ethnographer Richard Heath contributed an article titled ‘Politics in Dress’. A feature on fans as a feminine symbol pointed out that they were originally carried by men as a sign of power, while one on gloves asked why men, once such decorative dressers, had become so ‘sober’. In ‘Women Wearers of Men’s Clothes’, published in January 1889, Irish-born journalist Emily Crawford insisted that women who adopted masculine styles could accomplish ‘heroic duties’, while novelist Ella Hepworth Dixon applauded the ‘semi-masculine and completely appropriate gear’ adopted by women who rode.

Wilde joined the debate in his very first ‘Literary and Other Notes’ by declaring that, in time, ‘dress of the two sexes will be assimilated, as similarity of costume always follows similarity of pursuits’ (WW, I, 40). He also castigated the ‘absolute unsuitability of ordinary feminine attire to any sort of handicraft, or even to any occupation which necessitates a daily walk to business and back again in all kinds of weather’ (I, 40). In his opinion, restrictive clothing prevented women from taking their rightful place alongside men. Insisting that ‘the health of a nation depends very much on its mode of dress’, Wilde described how ‘from the Sixteenth Century to our own day there is hardly any form of torture that has not been inflicted on girls and endured by women, in obedience to the dictates of an unreasonable and monstrous Fashion’ (I, 40).

Education and Employment

Education too was a key focus of The Woman’s World. In January 1888, in his review of Women and Work, a collection of essays by poet and philanthropist Emily Jane Pfeiffer, Wilde quoted Daniel Defoe, who had asked ‘what has the woman done to forfeit the privilege of being taught!’ (WW, I, 135-56) He commissioned articles on the women’s colleges and on Alexandra College in Dublin, an all-girls institution of higher education. He also published a series of articles encouraging those few, fortunate women who had benefitted from access to higher education to explore opportunities opening up to them in the professions.

Several articles in The Woman’s World drew attention to the blight of poverty that afflicted women and their children. In several instances, the authors of these articles proposed solutions that went far beyond the usual ineffectual charitable works. In ‘Something About Needlewomen’, published in May 1888, trade unionist Clementina Black, who had helped establish the Woman’s Trade Union Association, highlighted the plight of impoverished needlewomen who were unable to earn a living wage from the piecework they were given. She encouraged them to combine into cooperatives. In July 1888, in one of several features dealing with Irishwomen, Irish journalist Charlotte O’Connor Eccles drew attention to the alarming conditions endured by Dublin’s women weavers, and insisted that their poverty should be alleviated through education and training. Emily Faithfull, a member of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women, wrote of the duty of teaching girls some trade, calling or profession.

It is interesting that many of these themes found their way into Wilde’s stories, most notably ‘The Happy Prince’ and ‘The Young King’. His inclusion of the impoverished match-girl in the former must surely represent a nod to the fourteen-hundred women and girls who had gone on strike at the Bryant and May match factory in 1888, refusing to work until their appalling conditions and inadequate wages were improved.

Woman and Politics

Wilde tackled the contentious issue of politics head-on and was unequivocal in his support for the greater participation of women. Reviewing David Ritchie’s Darwinism and Politics in May 1889, he praised that author’s rebuttal of Herbert Spencer’s contention that, should women be admitted to political life, they might do mischief by introducing the ethics of the family into affairs of state: ‘If something is right in a family,’ Wilde countered, ‘it is difficult to see why it is, therefore, without any further reason, wrong in the state’ (WW, II, 390). He commissioned articles on the campaign for women’s suffrage and he helped Lady Margaret Sandhurst in her controversial bid to be elected to the London City Council by publishing in full a speech she had delivered.

Literature

Naturally, literature was a key focus of The Woman’s World. One of Wilde’s most rewarding tasks was the commissioning of new works of fiction from emerging and established women writers. The best article in the December 1887 issue, he told poet Louise Chandler Moulton, would be ‘a story, one page long, by Amy Levy . . . a mere girl, but a girl of genius’ (Moulton, 123). Levy had sent the story unsolicited. In response, Wilde commissioned a second story, two poems and two articles. He also championed South-African-born radical feminist Olive Schreiner who, agitated for greater access to political life and an end to the sexual double standard.

In ‘Literary and Other Notes’, Wilde gave what he called ‘special prominence’ to books written by women. The aesthetic and new woman writers he promoted included E. Nesbit, who he described as ‘a very pure and perfect artist’ (WW, I, 36); and controversial poet Rosamund Marriot Watson, who wrote as Graham R. Tomson. When Tomson became editor of aesthetic magazine Sylvia’s Journal in 1893, it was clear that she had learned much from her association with The Woman’s World.

Reaction to The Woman’s World

So what was the reaction to The Woman’s World under Wilde’s stewardship? In Oscar Wilde and his Mother, published in 1911, Wilde’s friend Anna de Brémont declared, ‘[S]ociety began to take Oscar Wilde seriously when he became editor of The Woman’s World’ (73). She described how the magazine caused a ‘flutter in the boudoirs of Mayfair and Belgravia’. Certainly, Constance and Lady Wilde’s drawing rooms were thronged with would-be contributors. The press response was similarly positive: ‘Mr Oscar Wilde has triumphed,’ declared the Nottingham Evening Post, ‘the first number of the “Woman’s World” has already appeared, and has, I believe, been sold out’. Praising Wilde for ‘striking an original line’, the Times hailed The Woman’s World as ‘gracefully got up…in every respect’.

Rival publication Queen admired the improved appearance and impressive array of contributors. The assessment of the St James’ Gazette must have delighted Wilde. ‘The Women’s World is a capital magazine for a married man to buy,’ its reviewer declared. ‘He tells his wife he got it entirely for her sake; but he may always find some very good reading for himself.’ The Spectator decided: ‘The change is undoubtedly one for the better, in the sense of the higher’. Describing the articles as ‘extremely bright and useful’, the Irish Times recorded how, on the evening of the launch, ‘[T]here was not one in the West End to be had for love or money and impatient people could only get through the interval between Saturday and Monday by borrowing copied from friends. Perhaps the most significant reaction of all came from The Englishwoman’s Review, the organ of the suffragist movement in Britain. While refraining from praising The Woman’s World overtly, it ran notices attracting the attention of readers to more progressive articles.

Disillusionment

Under the terms of his contract, Wilde had agreed to spend two mornings a week in the offices of Cassell & Company. After a while, Arthur Fish could tell ‘by the sound of his approach along the resounding corridor whether the necessary work to be done would be met cheerfully or postponed to a more congenial period’. On a good day, there would be ‘a smiling entrance, letters would be answered with epigrammatic brightness, there would be a cheery interval of talk when the work was accomplished, and the dull room would brighten under the influence of his great personality’ (18).

Fish never doubted Wilde’s commitment to The Woman’s World and he described how hard his boss fought to retain editorial control:

Sir Wemyss Reid, then General Manager of Cassell’s, or John Williams the Chief Editor, would call in at our room and discuss them [issues] with Oscar Wilde, who would always express his entire sympathy with the views of the writers and reveal a liberality of thought with regard to the political aspirations of women that was undoubtedly sincere.

Yet, Wilde’s tenure was short-lived. Much of his disenchantment was born of frustration rather than a lack of commitment: ‘I am not allowed as free a hand as I would like’ (Complete letters, 325), he told his friend Helena Sickert in October 1887. In a letter to Scottish writer William Sharp, he complained: ‘The work of reconstruction was very difficult as the Lady’s World was a most vulgar trivial production, and the doctrine of heredity holds good in literature as in life’(Complete letters, 332).

As early as December 1887, Cassells were objecting to the ‘too literary tendencies’ (Complete letters, 337) of The Woman’s World. In October 1888, Oscar asked the board to authorise the purchase of a story from Frances Hodgson Burnett, but her name never appeared. Nor did four illustrated articles he had hoped to commission from French explorer and archaeologist Madame Jeanne Dieulafoy. Wilde’s despondence deepened when Cassell’s refused to drop the price to sixpence or seven pence in order to attract a wider readership. Fish noticed that his interest was waning: ‘After a few months,’ he remembered, ‘his arrival became later and his departure earlier until at times his visit was little more than a call’. Wilde’s ‘Literary and Other Notes’ disappeared after the fourth issue and, although it was reinstated at Cassell’s instance, he began to miss his deadlines. It may sound trivial but one of the toughest challenges Wilde faced was Cassell’s strict no smoking policy.

Fish had once described his boss as ‘Pegasus in harness’ and now he was pulling at the reigns. A typical day towards the end of his tenure went as follows: ‘He would sink with a sigh into his chair, carelessly glance at his letters, give a perfunctory look at proofs or make-up, ask “Is it necessary to settle anything to-day?” put on his hat, and, with a sad "Good-morning", depart again’ (The House of Cassell, 134). In April 1889, Wilde informed the Board of Inland Revenue that he would be leaving Cassell & Co. in August. His final ‘Literary and Other Notes’ appeared in June 1889, and by October his name was gone from the cover.

After Wilde’s departure, The Woman’s World reverted to its unadventurous roots. A renewed focus on fashion prompted The Woman’s Penny Paper to scold: ‘To dress is surely not considered the first or the only duty of women, even by their greatest enemies’. The magazine was discontinued shortly afterwards. Wilde had not neglected his own work during his two-year tenure as editor. Dozens of his poems, reviews, essays and stories were accepted by various periodicals during this time and he also published and promoted his first collection of stories, The Happy Prince and Other Tales. The break with Cassells heralded an exceptionally productive period that saw the publication of two further collections of short stories: Lord Arthur Saville’s Crime and Other Stories, and The House of Pomegranates; a collection of essays called Intentions; and The Picture of Dorian Gray, his only novel. While Wilde’s sincerity and sympathy were never in doubt, his interest in coping with the day-to-day challenges of bringing out a magazine on someone else’s behalf certainly was.

References

Chandler Moulton, Louise. The Literary World: a Monthly Review of Current Literature 20.8 (1889): 123-27.

De Brémont, Anna. Oscar Wilde and His Mother: A Memoir. London: Everett & Co. 1911.

Fish, Arthur (A). ‘Oscar Wilde as Editor’ Harper's Weekly. 58 (1913): 18-20.

Anon. The Story of the House of Cassell. London: Cassell & Co, 1922. 114-46.

Wilde, Oscar, The Complete letters of Oscar Wilde. Eds. Holland, Merlin and Rupert Hart-Davis. London: Fourth Estate, 2000.

Wilde, Oscar (Ed), The Woman’s World. 2 vols. London: Cassell & Company, 1888.

Created 16 September 2015