Left: Ruskin's House at Denmark Hill. Right: Ruskin's House at Herne Hill. Both from Volume 35 of the Library Edition. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In October 1842, the upwardly mobile Ruskin family acquired the remaining thirty-six years' lease, for the sum of £4800, on a more spacious house and garden at 163 Denmark Hill, only a mile or so from their previous home at Herne Hill. This was a much more comfortable property in which the Ruskins could entertain more freely and provide good hospitality. The wine cellar alone was one of the most comprehensive and of the highest quality, as befitted a good wine merchant. John James Ruskin’s stock included thirty dozen Cockburn Port bottled in 1840, twenty-three dozen Harris Port bottled in 1830, twelve dozen Muscatel, sixteen dozen pints and over thirteen gallons of Paxarete (a sweet wine used for blending sherry), and one hundred and nine dozen bottles and fifty-four gallons of sherry. (Dearden, Ruskin’s Camberwell, 16. The information was taken from the "Account Book of John James Ruskin 1845-1863," Ms 29, Lancaster). In addition there were large stocks of fine wines. Over nearly three decades, until 1871, many famous writers, artists, politicians, friends and acquaintances would be welcomed at this beautiful villa. Among these were Turner, Samuel Prout, Charles Eliot Norton, Henry James, Richard Fall and Robert Browning. Gordon was one of the first guests and stayed for almost a week in January 1843. His arrival was recorded in Ruskin's diary entry of 21 January: "Gordon came today – and always full of mind. He says when anything like the planned assassination of Sir R. Peel in papers to-night – takes place, nobody does anything naturally – nobody asks, but every body inquires" (Ms 3, fol. 123, Lancaster).

One of their conversations centred on religion. Ruskin's report reveals Gordon's High-Church leanings, recounting his dislike of Martin Luther and his repudiation of the doctrine of justification by Faith to which Luther adhered:

I am quite sleepy and tired to-night, though I have had some interesting conversation with Gordon – who doesn't like Luther at all – [...] in one of his last letters to a friend [...] he [Luther] says – pecca fortiter – [...] Great point of dispute. G[ordon] says, is [...] not worship of images, nor of Virgin – but doctrine of justification in which the Romanists are right. ["Diary of John Ruskin 1840, 1843-1844, 1846", ref. Ms 3, folio 123, Lancaster; (cf. Diaries I, 239-40]

Pecca fortiter literally means "sin strongly". Luther believed that since God's forgiveness had no effect on the soul, consisting merely of overlooking, or as it were cloaking sins, those who sinned more offered greater scope for divine mercy. This was in contradiction to the Roman Catholic doctrine on grace, which was contrary to Luther's doctrine of justification which held that faith alone was sufficient for salvation, whereas the Catholic Church taught that good works were also needed.

Henry Melvill. From a contemporary illustration.

Both men attended a service at Camden Chapel, Walworth Road, Camberwell, where the Rev. Henry Melvill was the incumbent. Melvill's lengthy, Evangelical sermons – although perhaps not quite rivalling the four-hour orations of the seventeenth-century French churchman Louis Bourdaloue whose name was given to a ladies’ chamber pot – were structured according to a regular pattern familiar to his parishioners, with pauses enabling them to cough and clear their throats. This was one of his last appearances at Camden Chapel. His fame as a Ciceronian orator spread far and wide – Gladstone was among his admirers – and he was soon promoted to the Principalship of the East India College, Haileybury, a post he held until the college closed in 1858. He was also Chaplain to Queen Victoria. Gordon did not share Melvill's Puritanism, preferring Pusey’s Oxford Tractarianism, as Ruskin observed in his diary:

Sermon from Melville [sic] showing the duty of rejoicing. Gordon didn't like it – said it was not so positive a command as M[elvill] wanted to make out – preferred one of Pusey's, which affirmed that the Christian posture was one of constant humiliation. Melville [sic] said finely of the phrase – rejoice in the Lord – That the want of joy was caused only by looking for the cause of it to ourselves – for the real cause was, not that our faith was too strong to let Christ go – but that Christ was too faithful to let us go. [Ms 3, fol. 123, Lancaster (cf. Diaries, I, 240]

Out among the "nasty blue mist at Norwood" and "cold wind", Ruskin enjoyed a "pleasant walk with Gordon", perhaps peppered with theological questions (Ms 3, fol. 123, Lancaster). In Praeterita, Ruskin recalled how, only a few years before during their walks over the Norwood hills, he had tried to engage Gordon, unsuccessfully, in his [Ruskin's] "favourite topic of conversation, namely, the torpor of the Protestant churches, and their duty [...] before any thought of missionary work [...] or comfortable settling to pastoral work at home, to trample finally out the smouldering 'diabolic fire' of the Papacy, in all Papal-Catholic lands". Gordon, although about to be ordained, surprised Ruskin by avoiding the topic "with the sense of its being useless bother" (35.250). He knew that any such discussion at the time would have been futile and would have led to much friction for Ruskin was totally under the influence of his Evangelical and anti-Catholic mother. Ruskin was always trying to change the world, whereas Gordon's approach was more realistic. Gordon's attitude had been formed, Ruskin wrote in Praeterita, very early when "a keen, though entirely benevolent, sense of the absurdity of the world took away his heart in working for it" or, Ruskin added, "perhaps I should rather have said, the density and unmalleability of the world, than absurdity. He thought there was nothing to be done with it, and that after all it would get on by itself" (35.250).

Ruskin was an avid theatregoer, and took Gordon to Drury Lane to see Macbeth, with the great Shakespearean actor William Charles Macready in the central tragic role. Ruskin and Gordon reacted quite differently to the play; Ruskin with detached but hyperbolic dislike as demonstrated by the underlining in his diary, Gordon with strong emotional attachment and sensitivity. Late on the evening of 24 January, while politely waiting for his guest to return from a christening, Ruskin wrote in his diary:

I am getting quite dissipated – out at Drury Lane last night. Macready in Macbeth – wretched beyond all I had conceived possible. – quite tired and bored – but Gordon liked it – and as it was for him I went, I was well pleased. I was surprised to see him completely affected and upset by the scene where Macduff hears of the death of his children. [...] I am sitting up now only for Gordon, who has been out to a christening and mayn't be back till midnight, I dare say. [Ms 3, fol. 124, Lancaster (cf. Diaries, I, 240)]

Gordon's reaction to the stage deaths may have been due to the revival of thoughts of how his own grandmother had responded to the death of her only surviving son, George Osborne Gordon (Gordon's father) in 1822, and his funeral at Broseley Parish Church on 8 April. Perhaps in the course of their many conversations Gordon shed light on his reaction?

The weather had turned unusually mild for mid-January; it was 65 degrees Fahrenheit (the equivalent of 17.5 degrees Celsius) in the hall of 163 Denmark Hill "but with a small fire". Gordon and Ruskin enjoyed both the warm weather and "a pleasant saunter" to the zoological gardens with "many new animals" (Ms 3, fol. 124 Lancaster).

Left: Dulwich Picture Gallery. Right: Destruction of Niobe's Children by Crescenzio Onofri (c.1632–c.1712) (attributed to), Courtesy of Dulwich Picture Gallery and ArtUK. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

One of Ruskin's favourite places in the vicinity was Dulwich Picture Gallery and on Gordon's last day, they "sauntered" there. On this, the diary is laconic. How interesting it would have been to know Gordon's opinions on The Destruction of Niobe and her Children, or Salvator Rosa's Mountainous Landscape with a River, the subject of discussion in Ruskin's chapter "On Inferior Mountains" in Modern Painters. On the last "pleasant evening" of Gordon's stay, two other friends were present; Gordon's only sister, Jane, then aged twenty-six, and Richard Fall (Ms 3, fol. 124, Lancaster). We do not know whether Jane was also staying at Denmark Hill or whether she had been invited solely for the evening. Richard Fall lived nearby at 44 Herne Hill.

27 January 1843 marked Gordon's departure, and left Ruskin feeling alone and bereft of his company. He wrote: "Gordon left us today, and I miss him very much, kind fellow, and clever as kind" (Ms 3, fol. 124, Lancaster). Ruskin accompanied Gordon into central London, probably by coach and horses, from where he would have travelled back to Oxford. Perhaps to counteract his feelings of loneliness and sadness, Ruskin immediately called on Turner. Fortunately, he "found him in – & in excellent humour" (Ms 3, fol. 124, Lancaster). But the visit was not entirely for palliative reasons. Turner was very much on Ruskin's mind, for he was in the throes of completing his first major work Modern Painters, a defence of the great English landscape painter. It was more than "beginning to assume form" as Ruskin suggested, but nevertheless emphasised, in his diary on 26 January 1843, for it was published in the first week of May 1843 (Ms 3,fol. 124, Lancaster cf. Diaries, I, 240 where the emphasis is omitted).

Three portraits of Ruskin by George Richmond (36.280 and 16.frontispiece, and 3).

For part of the summer term, Ruskin returned to Oxford, this time without his mother, to satisfy residential requirements relating to the award of his M.A. This was an opportunity, at last, to be alone in Oxford with Gordon. They discussed religion, and it would have been more sensible if Ruskin had shown more discretion and had not conveyed Gordon’s religious beliefs to his mother. There was a strong difference of opinion between Margaret Ruskin’s dogmatic, self-righteous, evangelical views and those of Gordon. She admonished her twenty-four-year-old son, and Gordon, in a letter (to her son) of 12 June 1843:

What strange whims even men of first rate talents get into their heads. Does Mr. Gordon forget that we have an Almighty Intercessor? … I am sorry, very sorry, that such differences should take place anywhere, but more especially that they should have arisen in Oxford. What are the real doctrines of what is termed Puseyism? Why do they not state them fairly and in such plain terms as may enable people of ordinary understandings to know what they think the truth? Any time I have heard Mr Newman preach, he seemed to me like Oliver Cromwell to talk that he might not be understood … Surely our Saviour’s consecration must have effected a change in the elements if an ordinary minister can; but I beseech you to take nothing for granted that you hear from these people, but think and search for yourself. As I have said, I have little fear of you, but I shall be glad when you get from among them. [Burd II, 740]

Her hypocritical order to "think and search for yourself" was really, "think as I do".

Any differences of opinion were set aside, and Gordon was invited again to stay at Denmark Hill the following year, 15-19 January. Details are sketchy. The two friends enjoyed their shared interests in art and geology and, as before, Ruskin was deeply sorry when Gordon left. They went to the Geological Society of which Ruskin had been made a Fellow in 1839. Ruskin did "a little oil painting and drawing, and some brushing up of head with G[ordon]" (Diaries, I, 260).

In spite of suffering from a "horrid cold" which got worse and worse, Ruskin was not deterred from making the journey to Tottenham Green, then a pleasant village to the north of London. He wanted to introduce Gordon to Benjamin Godfrey Windus (1790-1867) and to his Turner paintings. Windus, a retired coachmaker, was an avid and astute collector of Turner's works and those of other artists. He had acquired a substantial collection, housed in the library of his villa that he allowed people to visit, usually once a week. It was almost a private Turner gallery but Ruskin had "the run of his rooms at any time" (3. 234, note), enabling him to have access to source material for Modern Painters. Ruskin considered that apart from himself, Windus was the only other person who "cared, in the true sense of the word, for Turner" (3. 235, note). It was Ruskin's second visit that week to Windus's; his obsession with Turner was unabated. Among the many drawings, watercolours and oils, Gordon may have seen Glaucus and Scylla, Tynemouth, and The Lake of Zug. Ruskin's diary entry records that they had a "pleasant day" (Diaries, I, 260). The scarcity of diary entries during Gordon's stay may to some extent be due to Ruskin being incapacitated by the severity of his cold. "I haven’t had so bad a cold for years: thoroughly incapacitated for everything to-day", he wrote on 19 January (Diaries, I, 260).

But something was troubling Gordon during that short, winter stay. Ruskin was aware of it, but so tactful and sensitive was he to his friend’s emotional state that he refrained from violating Gordon’s need for privacy. It was not until several weeks later that Gordon confided to Ruskin what must have been his doubts about the latter’s pursuit of art as a career and a lifetime occupation: that was what had been on his mind during the Denmark Hill stay in January. It is through Ruskin’s lengthy response of 10 March 1844 that we not only surmise Gordon’s problem but we enter deeply into Ruskin’s mind. He reveals for the first time the tensions he felt about commencing what became Modern Painters and his dilemma about his future career. He asks Gordon for advice and lists, in a penetrating study of self-analysis, seven reasons why he is not suited to be a clergyman, as his mother wished. Broadly the main characteristics of his mind are, he writes, "to mystery in what it contemplates and analysis in what it studies". He continues like a performer on stage in an entertaining, yet self-mocking manner. One can almost hear the laughter at the end of each cadence:

It [Ruskin’s mind] is externally occupied in watching vapours and splitting straws (Query, an unfavourable tendency in a sermon).

Secondly, it has a rooted horror of neat windows and clean walls (Query, a dangerous disposition in a village).

Thirdly, it is slightly heretical as to the possibility of anybody’s being damned (Q. an immoral state of feeling in a clergyman).

Fourthly, it has an inveterate hatred of people who turn up the white of their eyes (Q. an uncharitable state of feeling towards a pious congregation).

Fifthly, it likes not the company of clowns – except in a pantomime (Q. an improper state of feeling towards country squires).

Sixthly and seventhly, it likes solitude better than company, and stones better than sermons. [3.666-67]

Gordon already knew these aspects of Ruskin’s personality and would not have been in the least surprised. Ruskin’s letter ends with a mention of an unknown lady: "We are all glad to hear Miss G. is better." Miss Jane Gordon, perhaps?

During the Easter Vacation, two days before Good Friday, on 3 April 1844, Gordon and an unnamed male friend, "a pleasant fellow", were invited to lunch at Denmark Hill. Gordon stayed on for dinner where he met some of Ruskin’s distant Scottish relatives, the Tweddales. "I enjoyed myself much", Ruskin wrote in his diary, "though the Tweddales were rather stupid company for him [Gordon] at dinner". "It was", Ruskin continued, "a glorious day – for weather – cloudless sky, intense blue, but wind a little cold – though from the west." At the end of this happy day, in which Ruskin had also sketched "a bit of fine trunk", he walked with his guests as far as the Elephant and Castle – a distance of about three miles in the direction of central London – "and sauntered back in great luxury" (Ms 3, fol. 189, Lancaster).

Saturday 28 April 1844 marked an important step, demonstrating Ruskin’s celebrity status as a sought-after young writer, author of two editions of Modern Painters I, published within a year of each other, in early May 1843 and on 30 March 1844. He was invited, without his parents, to the home of Sir Robert Harry Inglis (1786-1855) in fashionable, aristocratic Bedford Square, in central London, a stone’s throw from the British Museum. Sir Robert Inglis was at the time MP for Oxford University, a seat he held from 1829 until 1854. The invitation was most likely to a breakfast party, for Ruskin was back at Denmark Hill the same day by two o’clock. Sir Robert had gathered together around his table a glittering array of interesting and influential people of varying ages; twenty-five-year-old Ruskin was the youngest member of the party. Among these were Lord Northampton – Spencer Alwynne Compton, second Marquis of Northampton (1790-1851) who was President of the Royal Society between 1838-1849 –, Lord Arundel and the historian and politician Lord Mahon, afterwards 5th Earl Stanhope (1805-1875). There was the eighty-one-year-old poet Samuel Rogers (1763-1855) whose book of poems Italy, with illustrations by Turner, had first aroused Ruskin’s interest in that country. Another guest was the arctic explorer Sir John Franklin (1786-1847), "the North Sea man" (36.37) as Ruskin reminded his father. Franklin, after a distinguished naval career in the Napoleonic wars, was best known as a national figure who had brought fame to his country through his exploration of vast, unknown wastes in northern Canada. He had recently returned from a nine-year spell (1834-1843) as governor of the penal colony of Tasmania (known as Van Diemen’s Land until 1855). Franklin never returned from an expedition attempting unsuccessfully to break through the North-West Passage: he died heroically frozen in the packed ice in 1847 where his body remained until it was discovered in 1859.

Left: Sir John Franklin from the National Maritime Museum’s exhibition about the Franklin Expedition. Middle: Sir John Franklin's men dying by their boat during the North-West Passage expedition by William Thomas Smith, 1895. Right: Sir John Franklin on Matthew Noble’s Franklin Expedition Monument in Waterloo Place, London. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Sitting immediately next to Ruskin was the M.P. for Pontefract, Yorkshire, Richard Monckton Milnes, later Lord Houghton (1809-1885), with whom Henry James stayed in 1879. The presence of this charismatic, often larger-than-life figure filled the dining room; he liked young Ruskin and "chatted away most pleasantly" (36.37) to him, asking him to go and see him. They exchanged visiting cards, but when did they next meet?

Ruskin was showered with other invitations, from Rogers, from Lord Northampton to breakfasts and soirées. "Will you come and have breakfast with me – Tuesday at 10?" Rogers asked Ruskin (36.37). Ruskin accepted and arrived at 9.30 punctually on 1 May 1844 but was told he had arrived an hour too soon (Diaries, I, 274). He was launched. However, writing required solitariness and single-mindedness, and Ruskin sensed the perils ahead if he accepted all the invitations. This party served as an early warning to him. For in the following year, his need to be alone in order to concentrate on a second volume of Modern Painters was uppermost in his mind.

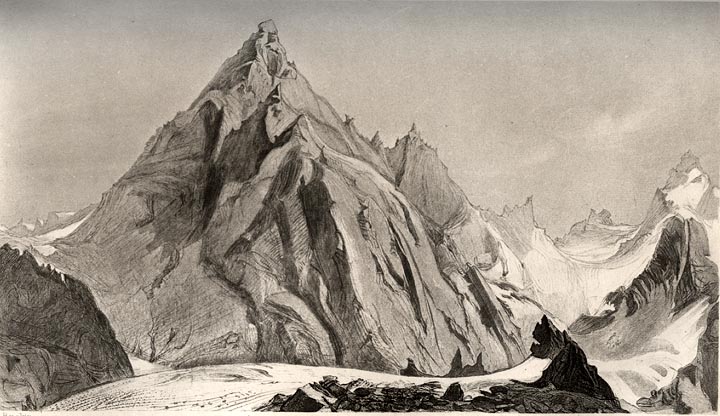

Left: The Aiguille Blaitiere. John Ruskin. c. 1865. Source: facing 6.230. Right: Aiguilles, Chamonix (Le Grépon, Aiguille de Blaitière, Aiguilles du Plan). John Ruskin and Frederick Crawley. 1854. Daguerreotype. Collection: Lancaster.. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The annual Ruskin family continental tour of 1844 lasted over three months. After setting sail from Dover on 14 May, the family did not see the white cliffs again until 23 August. Geology was Ruskin’s main interest for most of this tour, so much of the time was spent in Savoy and Switzerland. Chamonix was the ideal base for four weeks in June and early July from which to explore mountains and their anatomy. Once again, Gordon joined the party but this time at intervals. In Chamonix, Ruskin made a drawing, Chamouni in Afternoon Sunshine, as a gift for Gordon. Compare this drawing, which is reproduced as a photogravure in the Library Edition (facing 3.240), to Turner’s The Valley of Chamouni, reproduced two pages earlier:

Left: The Valley of Chamonix. by Turner (left) and Ruskin (right) [Click on images to enlarge them.]

During the execution of the picture, Ruskin had expressed to Gordon the "constant vexation [he] suffered because [he] could not draw better", whereupon Gordon replied, simply: "And I should be very content if I could draw at all" (35.252). Gordon later gave this painting to his sister Jane who likewise enjoyed mountain scenery and walking. On his Alpine rambles, Ruskin was also collecting samples of plants and flowers that he saved in a green, leather-bound book, with a clasp, his Flora of Chamouni. His album contains dried samples of meadow plants, alpine plants, mosses, varieties of orchids, gentians and saxifrage accompanied by records and descriptions. Of the Saxifraga Cuneifolia he wrote: "This saxifrage, common everywhere, was growing in great luxuriance (June 9th) in the lower woods of the Pèlerins, whence I gathered these in my evening walk. But all the form of the flower is now lost" ("Flora of Chamouni 1844": An album of pressed flowers with notes on them by Ruskin (Ms 65, fol 13, Lancaster).

Old Houses at Geneva by John Ruskin (1819-1900). 1841. Watercolour. Source: 35.322.

On 7 July 1844, Ruskin and Gordon spent the day in Geneva, but Gordon, much to Ruskin’s chagrin and irritation, could not stay longer and had to return to Chamonix. Ruskin wrote in his diary (on 8 July) from St Gingoulph, a small town nestling in the southeast corner of the Lake of Geneva: "Yesterday at Geneva a dull day, though spent with Gordon; Everything going wrong – Tug [Ruskin’s dog] ill: no letter from Griffith – bad weather – Mont B[lanc] invisible – Gordon unable to go with us: forced to go to Chamonix with a stick of a pupil. I was very sulky all the way here –" (Ms 4, Lancaster). This suggests that Gordon was accompanied by one of his less robust students, "a stick of a pupil"!

Two of Ruskin’s depictions of Chamouni. Left: The Glacier des Bossons, Chamouni (21.35). Right: Chamouni (Frontispiece, volume II).

Gordon travelled from Chamonix and met Ruskin and his parents on 19 July 1844 at Zermatt, then a tiny Swiss town at the foot of the Matterhorn. Chamonix is to Mont Blanc what Zermatt is to the Matterhorn. As the crow flies, over the peaks, the distance between the two resorts is approximately 69 km/44 miles. But the only route possible for a human being would be via Martigny (meeting the Rhone), Sion, Sierre, Visp to Zermatt, a total of approximately 140 km. My rough calculations are: : Chamonix to Martigny 30 km; Martigny to Sion 25 km; Sion to Sierre 20 km; Sierre to Visp 30 km; Visp to Zermatt 35 km. The journey, on foot, would have taken several days; it would not have been easy. Gordon would have had to negotiate several cols and rugged, rocky terrain, through glacier passes; he may occasionally have used mules. Chamonix to Martigny was an eight-hour journey on mule-back. Effie wrote, from Chamonix, to her mother on Wednesday 17 October 1849 about getting from Chamonix to Martigny: "We leave tomorrow crossing the Tête Noir[e] and getting to Martigny next day. We ought to go in one day but eight hours on mule-back is too much for us and we are going to do half one day and do the next four hours next day." (Lutyens, Effie in Venice, p. 49; hereafter cited at Lutyens1).

If Gordon broke the journey halfway, very basic accommodation was available at the inn at Trient (Lutyens1 50). From Martigny to Sion he may have posted, whch Ruskin and Effie did in October 1849. We know that Gordon spent one night en route at Visp (Viège in French) in the very Catholic Canton of the Valais in south-west Switzerland. From Visp to Zermatt it was at least an eight-hour walk, such as that undertaken by the Scottish physicist and writer on the Alps, James Forbes, in 1841 (Forbes, 309). There was no railway from Visp to Zermatt until 1891; that reduced the journey time to two and a half hours. Gordon arrived first at Zermatt, not surprisingly tired and hungry, and his first thoughts on greeting the Ruskins were connected with food rather than the beauty of the Matterhorn "in full ruby, with a wreath of crimson cloud drifting from its top" (35.333) that so enchanted Ruskin. Gordon, Ruskin recalled, "met us with his most settledly practical and constitutional face" and the following dialogue ensued:

"Yes, the Matterhorn is all very fine; but do you know there's nothing to eat?" said Gordon

"Nonsense; we can eat anything here." Ruskin

"Well, the black bread's two months old, and there's nothing else but potatoes." Gordon

"There must be milk, anyhow." Ruskin

"You can sop your bread in it then; what could be nicer?" Gordon [35.333-34]

Gordon was thoroughly disappointed with the meagre menu – the hotel too was so very uncomfortable that the party only stayed one night – and Ruskin had to admit, although somewhat reluctantly, his agreement: "But Gordon's downcast mien did not change; and I had to admit myself, when supper-time came, that one might almost as hopelessly have sopped the Matterhorn as the loaf" (35.334). This unrefined but nutritional and healthy rye bread or rye loaf – the six-month-old pain de seigle that Henri de Saussure had described in his report on the region in 1796, in Voyages dans les Alpes, an influential book that Ruskin had received on his fifteenth birthday (35.334-35) – formed a staple part of the diet of these mountain people.

What an impressive sight the sunset was against the Matterhorn when the clouds eventually lifted and revealed "playing crimson lights over the sky, and the Matterhorn appeared in full ruby, with a wreath of fiery cloud drifting from its top – as Gordon said, like incense from a large altar" (Diaries, I, 304).

1845 was the year in which Gordon was appointed University Reader in Rhetoric. It was also the year in which the twenty-six-year-old Ruskin set off on his first continental journey (for seven months between 2 April and 4 November 1845) without his parents. But he never travelled alone. His valet George Hobbs accompanied him; Joseph Couttet, his faithful guide and fatherly factotum joined his entourage in Geneva. It was a stately, measured journey, for the most part in Ruskin’s private black and gilt calèche and horses; all the evidence pointed to a wealthy, well educated, perhaps rather spoilt, pampered young English gentleman travelling in a grand style. Young Ruskin was totally in charge, and his well-paid staff (Couttet received four francs a day clear for himself and in addition had free board and lodging) attended to his every whim. Couttet held an umbrella over him while he sketched, and made sure his master always took "a squeeze of lemon in his water" (4. xxv, note 1). As Ruskin journeyed across France, the Alps and Italy, he arranged to travel with, or meet up with different congenial friends and companions at various places en route. He needed the intellectual stimulation. He met his drawing teacher and artist James Duffield Harding in Baveno and went with him for several weeks across North Italy to Como, Bergamo, Desenzano, Verona and Venice. Ruskin was, as always, very busy, and totally absorbed in his work, for this tour was the foundation of the second volume of Modern Painters, published in April 1846.

Gordon had recommended that Ruskin read, with care and attention, The Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, by the sixteenth-century theologian Richard Hooker (1554-1600), "for its arguments and its English" (35.414). This Ruskin did, recalling in Praeterita that he left "no passage till [he] had put as much thought into it as it could be made to carry, and chosen the words with the utmost precision [he] could give them" (35.414). Gordon’s wise counsel was, Ruskin claimed, the basis of the style of Modern Painters II: "the style of the book was formed on a new model, given me by Osborne Gordon" (35.414). Ruskin attempted to partly imitate Hooker, whose style he admired, and also Samuel Johnson. However, there is a hint that Ruskin may have regretted his overdependence on Hooker, when, as John Batchelor points out in his biography, Ruskin wrote in 1883 of the shame and indignation felt on re-reading the somewhat pedantic Modern Painters II, "at finding the most solemn of all objects of human thought handled at once with the presumption of a youth, and the affectation of an anonymous writer" (Bachelor, 70).

Five weeks of the tour, between 29 May and 6 July, were spent in Florence. This was Ruskin’s third visit and his appreciation of its art and architecture was in stark contrast to his first impressions in November 1840 when he was grievously disappointed in many things – "the Uffizi collection, in general, an unbecoming medley, got together by people who knew nothing, and cared less than nothing, about the arts" (35.269): the church of Santa Maria Novella seemed to him ugly and he could not understand Michelangelo’s admiration for it. "Glad to get out of stupid Florence", was his pointed diary entry on 25 November 1840. But now, five years later, Ruskin was seeing Florence with different eyes. On revisiting the church of Santa Maria Novella, he was "very much taken aback" (4.xxxii). There were Cimabue’s Madonna, Orcagna’s Last Judgment in the chapel, Domenico Ghirlandajo’s frescoes, and "three perfectly preserved works of Fra Angelico" (4.xxxii). He studied Rubens in the Pitti Palace. He was desperately short of time, in spite of often working from five o’clock in the morning until late at night. The long daylight hours of early and mid-summer could not be wasted. Florence was a particularly rich storehouse for the subject of his next book and Ruskin worked relentlessly as the oppressive heat increased. The mosquitoes were a problem and Ruskin attempted to fend them off with some essence of lavender purchased from the monks' Spezieria at Santa Maria Novella (Ruskin in Italy, 137). He revisited Masaccio’s frescoes in the Brancaci Chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine; on a previous occasion he had sketched the background landscape of The Tribute Money, and discussed it in Modern Painters I (Plate XIII, facing 5.396). The realisation that Masaccio had achieved such greatness in art at such an early age and had died in his mid-twenties (more or less Ruskin’s age) goaded him to do more work. Gordon was never far from Ruskin’s fertile, cross-referential mind, and in this chapel he endowed his friend with a kind of eternity by connecting him with Florentine art. As he looked intently at a fresco of Masaccio’s head, painted by Masaccio, he saw in it "a kind of mixture of Osborne Gordon and Lorenzo dei Medici (the Magnifico)" (3.180). Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) identified the self-portrait as being that of St Thomas, the last figure on the right of the central group in The Tribute Money. Which painting of Lorenzo dei Medici did Ruskin have in mind?

Developing themes on concepts of beauty and imagination in art for Modern Painters II was a vast comparative undertaking that required extensive and intensive knowledge of paintings. As always, Ruskin combined the hand and the eye in order to remember and see. So he recorded detailed descriptions of his discoveries – Giotto’s frescoes of the story of Job in the Cappella dei Medici in the church of Santa Croce, works by Orcagna, Giotto’s Crucifix in the church of San Marco, Benozzo Gozzoli’s frescoes in the Riccardi Palace, tombs sculpted by Mino da Fiesole in the Badia. The aim of Modern Painters II, was twofold — as Ruskin explained later in Praeterita:

I had two distinct instincts to be satisfied, rather than ends in view, as I wrote day by day with higher-kindled feeling the second volume of Modern Painters. The first, to explain to myself, and then demonstrate to others, the nature of that quality of beauty which I now saw to exist through all the happy conditions of living organism; and down to the minutest detail and finished material structure naturally produced. The second, to explain and illustrate the power of the two schools of art unknown to the British public, that of Angelico in Florence, and Tintoret in Venice. [35.413]

It was about two o'clock on Wednesday, 18 June 1845. Ruskin was "in the Gallery" (36.50) – I assume the Uffizi –, when he met, coincidentally or by design, a "Mr and Mrs Pritchard". This was forty-nine-year-old barrister, John Pritchard, on honeymoon with his young bride, the former Miss Jane Gordon, the twenty-eight-year-old sister of Osborne Gordon. Ruskin had known Jane since at least January 1843 when he had entertained her at the Herne Hill family home (Diaries, I, 240). But for reasons unknown, he had never been introduced to her husband. It was a brief encounter – the Pritchards were leaving for Switzerland the following day – but a favourable one, as Ruskin commented to his father: "She is looking very well; he seems a nice person" (36.50).

Who was "Mr Pritchard", the middle-aged barrister who was enjoying art on that hot summer’s day in Florence?

John Pritchard

John Pritchard MP. By permission of the Northgate Museum, Bridgnorth.

John Pritchard (1796-1891) was, like Osborne Gordon, a Broseley man. After studies at Shrewsbury School, he joined the family firm of attorneys and worked alongside his elder brother George (1793-1861) and his father. Pritchard's father died at the age of seventy-eight at his residence, the Bank House, Broseley, on 14 June 1837. His death was followed two years later by that of his second wife, Fanny. In her will, she showed that same generosity of spirit found in the Pritchard family: she left £100 to be invested in government securities, the interest of which to be used for the purchase of warm clothing for ten poor women, to be given on St Thomas’s Day [21 December] (Kelly’s Directory 1900, 48). George Pritchard took over the practice as sole attorney in Broseley for several years (See Law Lists of 1839 and 1841).

After his "apprenticeship" in the family firm and increasing responsibility, Pritchard's position was more formally recognised when, on 10 June 1841, he was called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn. His marriage to Jane Gordon in 1845 opened many doors. Jane’s brother George (1815-1865) was also a banker/attorney and became a partner in the firm of Pritchard, Nicholas, Gordon and Co.. Pritchard entered not only the Ruskin family circle where he was warmly welcomed, but the enriching network of a non-banking, non-legal community. Ruskin’s many political, artistic, literary and academic contacts would have been stimulating and useful in furthering Pritchard’s ambition to be a MP. Ruskin enabled him to become a national figure, whereas his solicitor/attorney brother, George, remained a local figure embedded in Shropshire life, with his work focussed on the town and county of his birth. John Pritchard remained a loyal, trusted lifelong friend of Ruskin and his parents, and was one of the executors of John James Ruskin's will.

Left: Library, Lincoln's Inn. Middle: South end of the Great Hall, Lincoln's Inn. Right: Eight scenes from Lincoln's Inn from the 1887 Illustrated London News. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In the mountains

Gordon was also planning to spend much of the summer vacation of 1845 abroad, on a long tour in the Alps, Switzerland and Italy. His main companion was George Marshall (1817-1897), also of Christ Church. Marshall, five years younger than Gordon, matriculated in 1836 at the age of 18, obtained his BA. in 1840 and MA. in 1842. He would hold various posts in the College – Reader in Greek in 1846, Censor 1849-1857 – until leaving to become vicar of Pyrton, Oxon in 1857. Marshall remained a lifelong friend of Gordon's and wrote the first and only biography of him. Gordon and Ruskin were due to meet: the problem was where and when. Ruskin was not entirely free to choose his own itinerary: his father controlled the purse strings and so regarded it as his right and parental duty to influence the shape and timing of the tour. Each day Ruskin was under the irksome obligation to write to his parents and report fully on his activities. If he missed, there would be recriminations and questions. However, this obligation ensured a plentiful supply of letters and information enabling us to reconstruct events.

In a strange way, responsibility for arranging the meeting with Gordon became dependent on the whim of John James Ruskin. When Ruskin was in Florence at the beginning of June, Gordon was staying with his mother Elizabeth Gordon at her home at Linley Hall, about three miles from Broseley, where she had lived since at least 1841. [In the census return of 1841, listed at Linley were Elizabeth Gordon, aged 55; Jane Gordon, aged 20; Alexander John Gordon, farmer, aged 25. The ages given do not accord with the dates of birth obtained elsewhere and must be treated with caution and circumspection. The census was certified by Alexander John Gordon, Enumerator, on 14 June 1841: see Fiche H0107/0928/11 in SA, Shrewsbury.] Instead of contacting Gordon directly and discussing the matter with him, Ruskin wrote to his father via his mother:

Would you tell my father that if he thinks it best for me to go to the Alps at once, to write to Gordon at Linly Hall, near Broseley, Shropshire, and apologize to him for the letter I sent which I ordered to be paid, but which couldn’t be paid, I found afterwards, & to tell him that after the 15th July, I am to be found at Val Anzasca, or near it, for a month & that I will leave a letter for him at the post office Domo d’Ossola, saying where to find me, and that if he can take the mountains first, we will go to Venice together in September. [Ruskin in Italy, 109-10.]

In an age without telephone, telegraph or electronic communications, making such uncertain arrangements seemed doomed to failure – and that is exactly what happened. One can but imagine Gordon’s reaction and how stretched his tolerance must have been towards his good friend. Gordon had already sketched out his route with Marshall, taking into account an agreed meeting with Ruskin. Now things had changed.

On Friday morning 13 June, Ruskin informed his father: "I write to Gordon immediately, telling him to write me here, with his probable address (on the 1st July)" (Ruskin in Italy, 113). Because Gordon had changed his itinerary, at the last minute, to try and accommodate Ruskin’s, he had not had time to inform his sister and her new husband. Hence the comment in Ruskin’s letter, of 17 and 18 June, from Florence, to his father: "They didn’t know of Gordon’s change of route" (36.50).

Meanwhile, Gordon had reached Geneva! Ruskin recognised the confusion his letters were causing and commented to his father, from Florence on 3 July: "I’ve a letter from Gordon, at Geneva – nearly as unintelligible as mine" (Ruskin in Italy, 137).

From Florence, Ruskin went in a northerly direction to Milan, then towards Como and the Italian lakes. They reached Macugnaga, in Val Anzasca, on 23 July (he had told Gordon that he would be there "after the 15th July […] for a month"). Ruskin was now among the Pennine Alps "up in the clouds again" in view of his favourite peak Monte Rosa that "showed off tonight, brilliantly, like a good creature as she is". He was happy and looking forward to Gordon’s arrival: "Gordon wrote me from Geneva he should drop down on me here some day soon – perhaps he is pastured up by the weather at Saas" (Ruskin in Italy, 165). The Swiss village of Saas was almost directly north of Macugnaga but separated by fairly inhospitable terrain. It was at least a full day’s walk from Saas to Macugnaga, via the desolate Mattmark See and a climb over the pass of Monte Moro. Gordon did not arrive.

By 19 August, in Baveno, Ruskin’s anxiety was mounting. He was jittery, upset at having missed Gordon and fearful that the same thing might happen with his watercolourist friend J. D. Harding. He was also desperate – the word is not too strong – to have company and expressed his uncertainty and helplessness – "I don’t know what to do", was his heartfelt cri de cœur in a letter to his father: "I am fidgetty about Harding, for I have missed Gordon, who is now on his way home – and Acland is at the Shetland islands – and I want to see somebody. I have been a little too much alone" (Ruskin in Italy, 106). It was not until 23 August that light was shed on the Gordon mystery and the unfortunate way in which they had missed each other. In his letter to his father, Ruskin blamed Gordon, unfairly:

I have a letter from Gordon – he is going home from Lucerne. We missed each other in a most clumsy way, but it was more his fault than mine, for he never told me in his letter from Geneva where to write to him, so that I couldn’t tell him where I should be – the consequence was that he arrived at Milan on the Sunday [20 July], I having left on the Saturday [19 July] – he followed me to Como on Tuesday [22 July], by accident, saw my name in the book as off for Val Anzasca, & went off the other way, for Venice – and he would have been at Milan on the Saturday but that he got out of the steamer at Arona by mistake for Sesto Calende. (Ruskin in Italy, 182-83).

Gordon had taken a boat on Lago Maggiore aiming to disembark at the most southerly point on the Lake (Sesto Calende) from where there was a direct route to Milan. Arona is a small port on the western shore of the lake. This seems to have been Gordon’s first visit to Italy and his mistake can easily be understood in the circumstances. He certainly tried very hard to find Ruskin. What Ruskin did not seem to understand was that Gordon’s vacation was of a limited duration and that he needed to return to Oxford. Ruskin’s journey was of an almost indefinite length and with almost unlimited resources.

Ruskin continued to correspond with Gordon during this continental tour and sometimes shared these letters with his parents. There is an echo of this in Ruskin’s letter from Venice in which he told his father: "I enclose a letter to Gordon which perhaps may interest you a little" (Ruskin in Italy, 143).

Gordon was drawn to Chamonix in particular (he had been there with Ruskin in 1842 and 1844) and returned there with Marshall in 1845. But by now, the Oxford tutor was behaving like a student of Ruskin! As such, with his "keen perception and critical judgment", he was already Marshall’s guide in matters of Art and Nature. He knew Chamonix well and memories of observing Ruskin closely the previous year as he sketched the mountain scenery, in particular The Valley of Chamouni (Ruskin’s gift to Gordon), were fresh in his mind. He had shared Ruskin’s thoughts, had learned how to see through Ruskin’s eyes: Gordon knew Ruskin’s mind and personality more intimately than anyone. Marshall confirms Ruskin’s influence on Gordon:

Though Mr Gordon was not of a robust frame, he had an exquisite enjoyment of mountain scenery; and without attempting any dangerous ascents he had, perhaps, a truer appreciation of the peculiar beauties of rocks and glaciers than many who had penetrated further into their secrets. He took great interest in Mr Ruskin’s studies of nature, which he greatly values, and was constantly bringing his old pupil’s theories to the test of experience. [18]

Gordon gave the impression that he was not physically strong – as photographs imply – but his slight frame belied great strength and powers of endurance. He needed stamina for all those mountain walks and climbs with Ruskin. At Chamonix, Gordon was joined by several other Oxford friends: he took them on a Ruskinian pilgrimage to spend the day on the famous Mer de Glace. But Gordon did not engage a skilled and accredited guide – Couttet, one of the best, was away in Ruskin’s service at the time – or indeed any guide other than himself. It was foolhardy and, not surprisingly, a near disaster happened. On the return journey, the party lost their way and found themselves off the main tracks and had "carelessly come to a fork in the river, one branch of which lay between them and the Inn at Chamounix, only a short distance off in a straight line" (Marshall 18-19). There was at that point a difference of opinion between the young men: realising the danger, all except Gordon wanted to "make a considerable detour, and cross by a bridge further up" (Marshall 18-19). Gordon, impetuously, acted otherwise and, "divesting himself of part of his clothing, tried to wade, but, as the rest of the party feared, was swept away by the torrent, icy cold, and running with great rapidity". His companions acted instantly and with great presence of mind, running as fast as they could down stream to a point where "the river narrowed considerably, and where they hoped to rescue him" (Marshall 19). They waited in vain, fearing the worst. Eventually, they returned to the inn where they were staying and, to their great relief, found Gordon alive and well. His great physical strength had enabled him to reach the opposite bank of the dangerous stretch of water. Marshall adds a poignant touch of local colour to the episode:

A Savoyard peasant-woman, who had witnessed the adventure, took him under her special protection, and when we reached our quarters, after a long circuit, we had the satisfaction of finding the hero of the day taking his ease in his inn, and, except a few slight cuts, none the worse for his escapade. Those, however, who knew best the danger of his position were much struck by the coolness and address with which he extricated himself from his perilous dilemma. [Marshall 19]

News of this mishap reached Ruskin’s parents, and of course Ruskin. Writing in the comfort of the Hôtel de l’Europe, Venice, on 11 September 1845, Ruskin was clearly annoyed by what he considered to be his friend’s stupidity and recklessness. "I quite shuddered at Gordon’s adventure", he wrote to his father, "which I have never heard of before, but he ought to have had more sense". He added somewhat arrogantly: "I knew better than that at 14" (Ruskin in Italy, 199).

Responsibility for the missed appointments must rest in almost equal measure with both parties. In his relations with Ruskin – in Britain at least – Gordon does not seem to be an uncertain travelling companion, or someone who arrived for an appointment at the very last minute. However, in Marshall’s memoirs published in 1885, he is portrayed quite differently:

Mr Gordon was not good company for weak nerves. He was constantly on the verge of a catastrophe de voyage, which kept his fellow-travellers in a lively state of uncertainty as to his movements. It seemed utterly hopeless, when he was strolling somewhere about, leaving his effects in utter confusion, that he could be ready for boat or train, or any conveyance dependent on time or tide. But at the last possible moment he sauntered in to the place of starting with his usual abstracted air and leisurely gait and look of surprise at any symptom of impatience, though how chaos had been reduced to order was a secret known only to himself. [Marshall 19-20n]

Gordon's relationship with the Ruskin family was unharmed and he was a guest, along with John and Jane Pritchard, the dealer Thomas Griffith and wine merchant Robert Cockburn at 163 Denmark Hill on 12 December 1845 (Ms 33, Lancaster). This would appear to be the first time that John Pritchard was invited, and would be the first of many such occasions.

Last modified 14 March 2020