[Thanks to James Heffernan, founder and editor-in-chief of Review 19 for sharing this review with readers of the Victorian Web. — Katherine Miller Weber]

his book charts a new course through British visual culture of the long nineteenth century, a course neglected by traditional art and cultural histories. Arguing for a distinctly Chinese way of seeing that emerged with Britain's growing economic and cultural contact with East Asia—from Lord Macartney's embassy in 1793, through the Opium Wars of mid century, to the Boxer Rising of 1898-1901—Elizabeth Chang guides the reader across the ubiquitous Victorian landscapes of willow trees and arched bridges, emblazoned on prints and porcelain plate in the middle-class home, to their jarring urban counterpoint, the smoky opium den.

his book charts a new course through British visual culture of the long nineteenth century, a course neglected by traditional art and cultural histories. Arguing for a distinctly Chinese way of seeing that emerged with Britain's growing economic and cultural contact with East Asia—from Lord Macartney's embassy in 1793, through the Opium Wars of mid century, to the Boxer Rising of 1898-1901—Elizabeth Chang guides the reader across the ubiquitous Victorian landscapes of willow trees and arched bridges, emblazoned on prints and porcelain plate in the middle-class home, to their jarring urban counterpoint, the smoky opium den.

In cultural terms, the willow trees and arched bridges reassured Britons of the static antiquity and incipient decline of Chinese civilization, which stood ripe for Western development. But in art-historical terms, Chang argues, the impact was quite the opposite. From the willow pattern to the opium den, Chinese (and pseudo-Chinese) visual iconography and style constituted a necessary insurgent precursor of modernism within the Victorian realist regime, an uncanny form of anti-real or even surreal representation she calls "exotic familiarity." The range of texts Chang assembles to explore this paradox of nineteenth-century British orientalism is impressively eclectic: from the travel narratives of Barrow and the little-remembered Robert Fortune, to the satires of Hazlitt and Hunt, to novels by Meredith and Dickens. Principally descriptive or ekphrastic, these texts give literary context and conceptual density to the visual media—prints, porcelains, photographs—that saturated British visual and commodity culture in the century after the first vogue for chinoiserie.

The excellent first chapter traces the influence of Chinese gardens and landscape design on British imagination of the East. The fact that the French perceived in British landscape design an identifiable style—anglo-chinois—is a choice example of the "exotic familiarity" driving British reception of Chinese visual aesthetics. The compositional and botanical familiarity of the Sino-English willow garden required perpetual estrangement, achieved through an orientalist rhetoric that encoded the Chinese garden as "despotic, excessive, fantastic, incoherent, illogical, and exotic" (24). At least in part, terms such as these sprang from the episodic antagonisms and violence of Sino-British relations during the very period when British consumers avidly collected scenes of Chinese imperial gardens for display in their homes. According to the colonial narrative, revenge for Lord Macartney's rejected diplomatic overtures in the Qing gardens in 1793 was exacted by Lord Elgin's looting and burning of the Summer Palace and its grounds in 1860, when photographs could record the just devastation of a "despotic" landscape already "exotically familiar" to the British public. But in William Chambers's widely read Dissertation on Oriental Gardening (1772), Chang argues, we find a subversive countercurrent in British orientalism, for Chinese aesthetics primed British eyes for European modernism: "an Oriental garden offers a model of diversity within singularity that betokens the viewing experience of the modern subject, able to occupy more than one perspective at a time" (32).

The second chapter, a highlight of the study, shows how Chinese landscape aesthetics was popularized in England through the ubiquitous willow-pattern adorning Victorian porcelain dishware. Though Chambers and Barrow might have been widely read among the lettered classes, the willow-pattern plate represented a true Asian invasion, bringing Chinese iconography to the dinner tables of the general populace. In the Victorian era, after Chinese plate had been imported for centuries, the Staffordshire factories tightened their stranglehold on porcelain production and thereby fully anglicized the willow pattern. In the willow-pattern plate, the anglo-chinois style was commodified, becoming by its very foreignness and departure from dominant realist pictorialism—linear perspective, scale—an icon of bourgeois comfort and normalcy, even tedium. In this context, I wonder that Chang's discussion of the late Victorian plate collections of Whistler and Rossetti does not contain some pondering on the afterlife of the Romantic-era willow pattern as camp. At least she might have explained more thoroughly how the unchanging pattern could circulate between avant-garde and middlebrow contexts so seamlessly and for so long. Meredith's The Egoist provides a partial answer. As Chang notes, the novel aims less to examine the willow picture than to mirror its narrative—a girl's escape from an arranged betrothal to her pastoral lover—"which offers a model of narrative enslavement that Meredith can exploit for his own ends." (93)

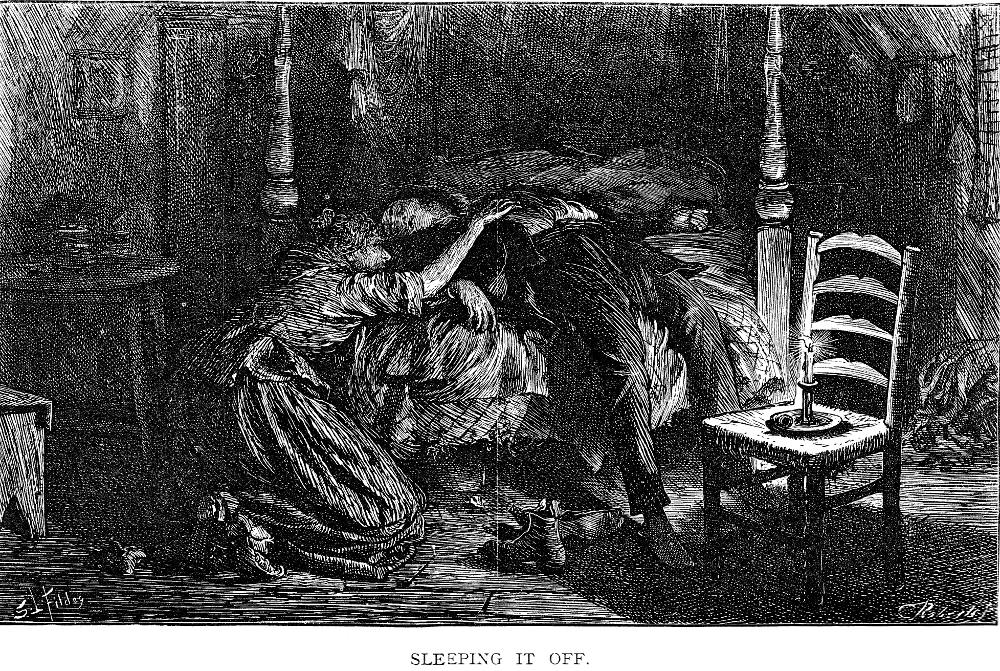

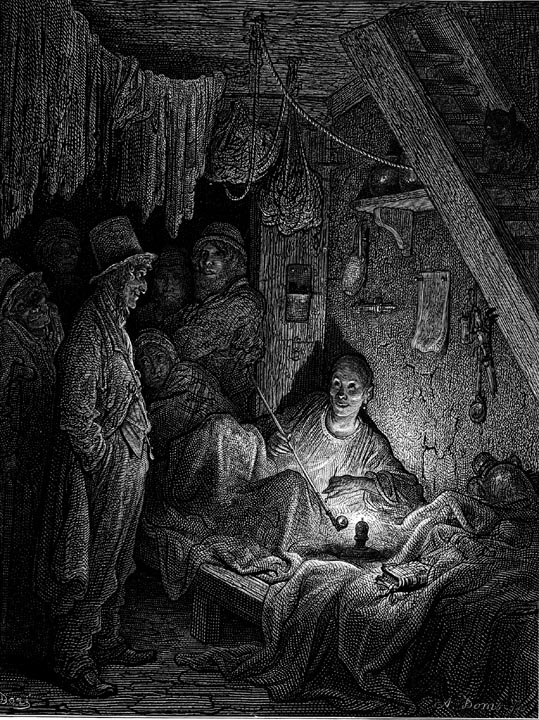

Through illuminating readings of the fiction of Dickens, Conan Doyle, and Wilde, Chang's third chapter shows how the opium den came to serve as "a persistent spatial shorthand denoting corrupting iniquity" (110). For Chang, the smoke-filled den, often littered with drugged bodies, represents a "gothic parallel" to the official exhibitions of Chinese wares and culture at the Great Exhibition and elsewhere during the mid-century period between the two Opium Wars. While China's ostentatious place within the integrated High Victorian global marketplace belied the colonialist rendering of China as backward and remote, the image of the opium den reinforced it by depicting China's population as enfeebled and effeminized by addiction. In an iconic episode such as the opening to Dickens' Edwin Drood, the opium den is "a fundamentally misrepresented and misrepresenting space." (140)

Three illustrations of Edwin Drood: Left two by Luke Fildes: In the Court and Sleeping It Off. Right: Opium Smoking — The Lascar's Room from by Gustave Doré. Images not in original review. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Chapter four shows how the advent of photography provided another challenge to the willow-plate rendition of an antique and unreal China. Yet the challenge was met, or more precisely evaded, by three photographers who finessed the paradox of a cloistered atemporal foreign landscape brought within the gaze of a technology promising historical immediacy and the real. In the work of these Victorian-era photographers, Chang finds, "the fantasy of a fully embodied, and therefore fully real vision, of China continues to be deferred" (175). Just as early photographers adopted pre-photographic compositional formulae, so Victorian photographers in China took their cue from the willow-pattern tradition. Exacerbating the "crisis of representation" it embodied, they re-iterated the "exotic familiar" in their pictures of Chinese gardens, and even in the military photography of the Second Opium War, which found means to ritualize "Chinese acquiesence" to the inquisitive and acquisitive British eye.

If this sketch of the book's rich arguments and interdisciplinary archival reach is not sufficient endorsement, let me express my admiration for its lucid style and theoretical sophistication. The book certainly achieves what it promises: by its enlightening critical recovery of a neglected dimension of Victorian visual culture, it compels reassessment of that culture as a whole. Caught between the luxurious tastes of chinoiserie and bourgeois dinner tables, between the Great Exhibition and the opium den, between high art and low humor, Chinese visual aesthetics of the British long nineteenth century have long been slighted by literary scholars as well as specialists in visual culture. It has required a scholar of considerable interdisciplinary imagination and critical powers to render the complex weave of Anglo-Chinese aesthetic relations..

That said, I consider the first two chapters—on gardens and porcelain plate—measurably superior to the later ones. Chang mostly favors elaborate analysis of redolent examples over a general survey of primary sources. Readings of individual works are called upon to sustain her argument for larger aesthetic modes, or even whole epistemes. This method serves her well in the elucidation of genres such as the Chinese garden and the willow pattern plate. But it is less convincing when applied to individual and idiosyncratic texts or images, where the evidentiary sampling is a slender reed on which to build ambitious general statements about Chinese visual culture in Britain. In the introduction, for example, Chang's highly skilled, thorough, and elegant exposition of her thesis cannot hide the fact that her arguments, even at this early stage, lack a density of material examples. But this defect scarcely harms the manifest quality and importance of the book overall. In its syncretic handling of complex and disparate historical material, and its deft comparative treatment of multiple media and genres, Chang's book makes an outstanding contribution to scholarship on British orientalism, and exemplifies the new visual-cultural studies at its best.

Related Material

Bibliography

Elizabeth Chang Britain's Chinese Eye: Literature, Empire, and Aesthetics in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Stanford, 2010. viii + 238 pp.

Forman, Ross G. China and the Victorian Imagination: Empires Entiwned. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013. [Review by Mia Chen].

Last modified 11 July 2014