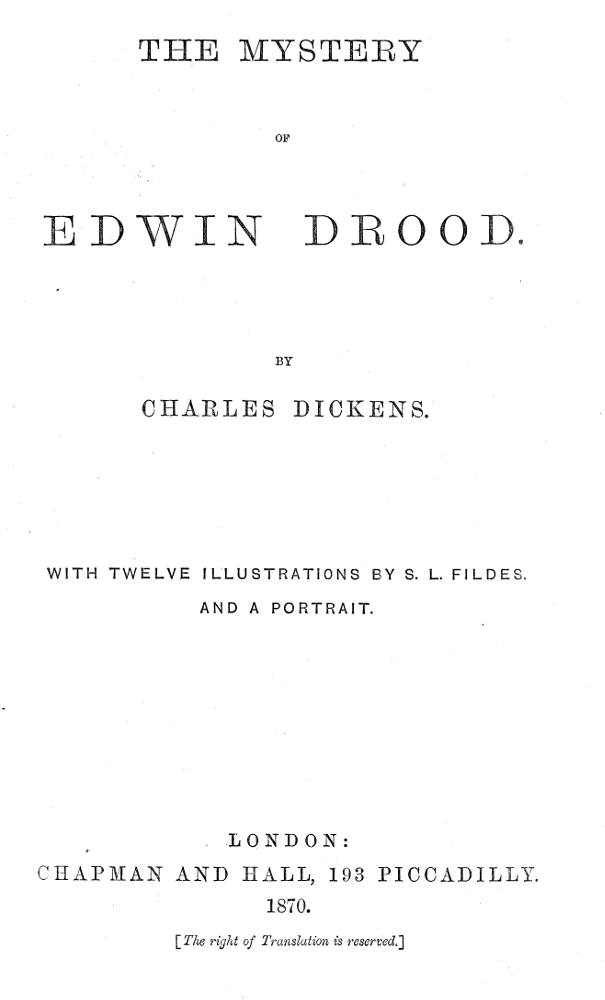

In the Court by Sir Luke Fildes for Charles Dickens's The Mystery of Edwin Drood (April 1870), facing p. 1, but positioned as the headpiece on page 1 for Chapter I, "The Dawn," in the Household Edition (1879); engraver, Swain. 10.0 cm high by 15.8 cm wide (4 by 6 ⅛ inches), framed and vertically mounted in the 1870 edition. [Click on the illustration to enlarge it.]

Commentary: The Setting as a Psychological Study

The backgrounds, too, were drawn from actual scenes, as for example, the opium-smokers' den which figures in the first and last illustrations; this was discovered by the artist somewhere in the East End of London; the exact spot he cannot recall, nor does he believe that Dickens had any particular den in his mind, but merely described from memory the general impression of something of the kind he had observed many years before. [Kitton, p. 211]

Lacking Dickens's ability to reveal John Jasper's public and private selves simultaneously, Luke Fildes focuses on the East End opium den in the opening plate, In The Court. In terms of his respectable middle-class clothing and his standing upright, John Jasper's figure contrasts that of the jumbled sleepers on the "large unseemly bed" in the first chapter, "The Dawn." To the right of Jasper (supporting himself with his right hand, his payment in coin clutched in his left), there is some semblance of order, the chair, table, and fireplace being far tidier than the confusion of figures and the ramshackle four-poster to the left. These humble, domestic realia represent the workaday world, while the chaos of the bed and its occupants suggests what critic Harry Stone has termed "the night side," the world of the subconscious, of horrible visions, of phantom cathedrals, and imagination (suggested by the initial references in the text to the Arabian Nights). The Lascar and the haggard woman (hardly recognizable as a woman) in the centre strive against their stupour, but cannot rise. Thus, the disposition of the figures has psychological significance. The passage illustrated occurs in the penultimate paragraph of the opening chapter:

As he falls, the Lascar starts into a half-risen attitude, glares with his eyes, lashes about him fiercely with his arms, and draws a phantom knife. It then becomes apparent that the woman has taken possession of this knife, for safety's sake; for, she too starting up, and restraining and expostulating with him, the knife is visible in her dress, not in his, when they drowsily drop back, side by side."

As yet the "He" of the passage, from whose perspective Dickens narrates the opening chapter in the limited omniscient, is not identified by name [John Jasper] when he "lays certain silver money on the table," but the image in anticipation of the final paragraph of the chapter establishes this focal character as (at least outwardly) not a denizen of this underworld but a representative of the respectable middle class, trying desperately in Fildes' plate to cling to his own identity and not to become merely another addict like the undistinguished heap of semi-humanity on the bed. Thus, even before the trext proper has introduced us to the hidden life of John Jasper and his narcotic-supplier (today, we would say "pusher") Princess Puffer, the plate opposite the title-page has prepared the reader for some of the book's principal issues and themes, notably the loss of self and the dangers of addiction, and has introduced us to one of the chief characters, John Jasper, who appears in a total of seven of the twelve illustrations (April through September, 1870). The artist's "deployment of heavy black lines and meaningful white spaces, especially in the interior or dimly lit scenes, satisfied the viewer's demand for representation while it left ample room for imagination" (Cohen, 223).

Scanned image and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane R. "Chapter 18: Luke Fildes." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp. 221-234.

Dickens, Charles. The Letters of Charles Dickens, ed. Graham Storey. Oxford: Clarendon, 2002. Vol. 12 (1868-70).

_______. The Mystery of Edwin Drood. With Illustrations [by Sir Luke Fildes, R. A.] London: Chapman and Hall Limited, 193, Piccadilly. 1870.

_______. The Mystery of Edwin Drood; Reprinted Pieces and Other Stories. With Thirty Illustrations by L. Fildes, E. G. Dalziel, and F. Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1879. Vol. XX.

Kitton, Frederic George. "Luke Fildes, R. A." Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. London: George Redway, 1899. 202-217

Paroissien, David (ed.). "The Illustrations," Appendix 3 in Charles Dickens's The Mystery of Edwin Drood. London: Penguin, 2002, pp. 294-299.

Created 24 October 2007 Last modified 17 July 2023