In this two-part appreciation, Sylvia Hornsby expands on an aspect of her doctoral thesis for Canterbury Christchurch University, Moving through Uncertainty with George Meredith (2023), in which she often notes that sensory awareness is part of the "ongoing process of moving towards harmony of body, mind and spirit" that Meredith shares with his audience. The thesis itself, with its wider range of approaches, is available online at https://repository.canterbury.ac.uk — Jacqueline Banerjee

Leave the noise and the smells of the city . . . Come and enjoy the sights, sounds, colours and scents of the countryside in spring. . . .

eorge Meredith’s invitation to share the sensory delights of the natural world is as appealing in the twenty-first century as it was in 1851, when he published his poem "Invitation to the Country" (Trevelyan 89). His poetry, celebrating the beauty of nature and revealing the influence of Wordsworth, is "filled with sensuous detail" as Rebecca Mitchell notes (251), and he expresses his philosophy of striving for harmony of body, mind and spirit, in a close relationship with the Earth.

Rossetti insistently exhorted by George Meredith to come forth into the glorious sun and wind for a walk to Hendon and beyond. by Max Beerbohm. Plate 13, Rossetti and His Circle, 1922. [Click on all the images on this page to enlarge them, and for more information about them.]

Part I of this essay, leading up to a consideration of Meredith's poem, "Invitation to the Country," focuses on sensory detail in his writing, demonstrating his love and knowledge of nature and skills of observation, and his understanding of the value of our interdependent sensory faculties. In this respect, his fiction can be compared with that of his contemporary Thomas Hardy, as both men were poets before novelists, and incorporated poetic techniques into their prose. In Part II, close readings from two of Meredith’s novels, The Ordeal of Richard Feverel and The Egoist, show his innovative use of natural details and imagery to depict settings in sensory terms, and as a means of characterisation; and the impact of this on his readers.

Although Meredith’s challenging style was neither popular nor commercially successful, he considered that experimentation was necessary as a means of moving towards a new form of novel. As a result, despite the general appeal of his attitude towards nature, his skill in expressing its attractions in sensory detail is not fully enough appreciated. Yet the way it contributes to the reader's own sensory experience is perhaps the greatest reward for the effort of tackling his work.

PART I

"Look you with the soul": Meredith’s keen observation

Meredith’s love of "Nature, birds and flowers, mountain and woodland, was innate" (Ellis 47), and aged fourteen, he attended the Rhineland school at Neuwied, where the study of natural history and botany was encouraged. His knowledge is recognised by William Sharp, recalling the opinion of Grant Allen who was himself "a lover and accomplished student of nature." Allen stated that Meredith knew the "intimate facts of countryside life as very few of us do . . . not in the terms of an ornithologist and botanist" but from detailed observation (qtd. in Sharp 2). A close relationship with the natural world is expressed in the third "Pastoral" in Meredith’s first collection, titled Poems (1851), where he declares, "A thing of Nature am I now" (50). His descriptions of nature in these early poems reveal his observational skill, a keenness of sight noted by his friends and visitors. His "quick, observant eyes," recalled by F.C. Burnand (qtd. in Hammerton 105), express his energy and vitality, and Frank Harris too described the "quick-glancing eyes which never seemed to rest for a moment on any object, but flitted about curiously like a child’s" (qtd. in Ellis 305). The skills of looking and learning were applied to people as well as nature; the two were intimately related. Meredith described himself as "an associate with owls and night-jars, tramps and tinkers, who teach me nature and talk human nature to me" (Cline 231). John A. Steuart recorded that "the eyes, light blue-grey and clear as a child’s, look up smilingly and shrewdly. They are worth studying, for they are the keenest eyes of this generation. They look through man and especially through woman . . . as if humanity . . . were diaphanous; but they look humorously, sympathetically" (qtd. in Hammerton 68). Notably, in "The Woods of Westermain" in Poems and Lyrics of the Joy of Earth, published in 1883, the poet suggests that it is possible to detect the spirit of Earth by reading the eyes of oxen, and looking "with the soul" (195).

Meredith's sensitivity to sound

William Hyde's illustration for Meredith's poem, "A Path through Trees" (The Nature Poems).

Nineteenth-century chemist and author George Wilson asserted the importance of cultivating sensory perception in his 1860 book The Five Senses: Gateways to Knowledge, recommending training the ear to appreciate the sounds of birds and the sea, winds and thunder - and music. Of all the senses, Wilson believed, hearing "most largely lends itself to . . . emotional, or . . . poetical" feeling (qtd. in Mitchell 274). Meredith’s sensitivity to sound is evident in both his correspondence and his creative work. Lionel Stevenson reports that, when visiting Scotland, he talked of "the sound of the stream tumbling down among the stones as one of the sweetest in nature" (287). Inviting a friend to visit in 1892, when restricted by spinal ataxia, Meredith wrote: "I dare say you do not mind the sound of rain on your hat. I liked the music when I was a walker" (Cline 1079). He conveys the "music" of nature memorably in "South-West Wind in the Woodland," when describing the sounds made by the trees in the woods. The "aspens . . . tinkle with a silver bell" (24) and "briared brakes . . . had sung / Shrill music" while "round the oak a solemn roll / Of organ harmony ascends, / And in the upper foliage sounds / A symphony of distant seas" (25). His poem "July" deals with a more universally appreciated auditory experience: birdsong. It concludes with four lines which evoke the different notes of cuckoo, dove, nightingale, ouzel, and throstle. This keenness of ear carries over into one of his best-known novels, The Egoist, when he vividly characterises the voice of a ten-year-old boy as "woodpecker and thrush in one" (246).

Meredith's responsiveness to scent and colour

Sensory awareness of scent and colour is apparent in widely Meredith’s life and work. His fondness for violets, expressed in an early poem "Violets," refers to the potency of their perfume though the flowers themselves may be "unseen" (16), and violets from his garden were sent to friends to give them a "scent of Box Hill" (Cline 1478). Briar-scent carried on the warm south-west wind reminds the poet of a meeting with his love in the orchard, smelling the juice of sliced ripe apple, and the sensuality of sharing the fruit ("Breath of the Briar," 411). His appreciation of the evocative quality of scent is noted in anthropologist Edward Clodd’s memory of Meredith holding "a bunch of bladder-weed . . . held to his nose as if fragrant as the choicest attar" (qtd. in Ellis 311). Both scent and colour can also serve to convey distaste. In criticising a book he dislikes, Meredith suggests that anyone who reads it "must smell putrid for a month" (Cline 889), and in Meredith’s novel Harry Richmond, sensory details evoke the sense of isolation in an unfamiliar city: Harry experiences London as an alien environment, as he endures the sensations of "traversing on a slippery pavement atmospheric circles of black brown and brown red, and sometimes a larger circle of pale yellow; the colours of old bruised fruits, medlars, melons, and the smell of them; nothing is more desolate" (114). More often, however, as in "Ode to the Spirit of Earth in Autumn," Meredith uses scent to express his philosophy of hope, looking ahead to the renewal of spring, as Earth smells of "regeneration / In the moist breath of decay" (177).

When response is impaired

The importance of instinctive observation, the value of sensory skills, and the interdependence of such skills and the imagination, become particularly apparent when faculties are restricted. In the poem "A Faith on Trial" the scents, colours and sounds of a familiar walk on a May morning are described for the reader, but the poet is suffering from grief during the illness of his wife. Recalling memories of their walks together, he is aware of, but unmoved by, the beauty of nature: it "passed like a bier" (346), and he "saw, unsighting" (347), still able "to observe," but "not to feel’ (349). However, his "disciplined habit to see" (350) eventually proves efficacious. The sight of the white wild-cherry tree in bloom compels him not merely to observe, but to feel. The sight of lively children restores his belief in the continuity of the natural cycle of life. Seeing himself as part of nature now, he bows "as a leaf in rain" (356).

After his wife’s death, Meredith notes in another poem, "Change in Recurrence," that although she no longer watches birds and animals in her garden, the blackbird continues pecking, the squirrel hops from cone to cone, and the thrush with a snail "tap-tapped the shell hard on a stone" (361). Unable to walk and increasingly deaf in his fifties and sixties, he continued to be a keen observer of people and nature, deriving comfort from his imagination, and a sort of vicarious pleasure from sensory memory. Although he is unable to hear now, sound is recalled as a feeling in "Song in the Songless":

They have no song, the sedges dry,

And still they sing.

It is within my breast they sing,

As I pass by.

Within my breast they touch a string,

They wake a sigh.

There is but sound of sedges dry;

In me they sing. [548]

A "stimulant to imagination": Sharing the sensory experience in "Invitation to the Country"

In his 1851 poem "Invitation to the Country," Meredith invites his readers or listeners to accompany him through the Surrey countryside, using their senses and imagination to share his love of the natural world. The poet urges the city-dweller to "Cast off the yoke of toil and smoke" and to "come, for the Country awaits thee with pity / And longs to bathe thee in her delight."

The changing season is depicted in physical sensations, as in the description of "Early Spring that shivers with cold" but "gathers, day by day, / A lovelier hue, a warmer ray." The poet's audience is encouraged by the personification of Nature in the countryside, and by the poet’s own personal appeal: "I no less, by day and night, / Long for thy coming, and watch for, and wait thee." The sights, sounds and colours of the natural world, are highlighted in descriptions of plants, birds and animals. "Spring is casting winter’s grey" and the "avenues of pines / Take richer green, give fresher tones, / As morn after morn the glad sun shines." The increasing warmth brings signs of life, as "Primrose tufts peep over the brooks . . . The marshes are thick with king-cup gold" and "Soon comes the cuckoo" with "her blue eye." The burgeoning Spring is evoked by "sweeter song, a dearer ditty; / Ouzel and throstle, new-mated and gay, / Singing their bridals on every spray." Then, "Clear is the cry of the lambs in the fold, / The skylark is singing, and singing, and singing" (89).

Emphasising the songs of the countryside in contrast to the city, the poet encourages the reader’s use of imagination, urging: "Oh, hear them, deep in the songless City!" The new season is experienced in sensations, and the energy of new life is represented in active verbs signifying the re-birth of plants and animals. The peeping primroses show "Fair faces amid moist decay! / The rivulets run with the dead leaves at play, / The leafless elms are alive with the rooks." "Over the meadows the cowslips are springing . . . The frog and the butterfly wake from their sleep."

Repeating the invitation to "Come, in the season of opening buds" in the final stanza, the poet demonstrates respect for the animals, directing: "Come, and molest not the otter that whistles . . . Let him catch his cold fish without fear of a gun." The concluding four lines of the poem show how sensations are shared between all living things:

And every little bird under the sun

Shall know that the bounty of Spring doth dwell

In the winds that blow, in the waters that run,

And in the breast of man as well. [89-90]

The beauty of spring is linked to the passionate emotions of first love, as part of the natural cycle of life, in "Love in the Valley." Like "Invitation to the Country," the first version of the poem was published in 1851 when Meredith was twenty-three years old, and the poet describes a girl who is part of the natural world, making comparisons with animals and birds. She is "Shy as the squirrel, and wayward as the swallow; / . . . Full of all the wildness of the woodland creatures" (573). Images are created in terms of scents and sounds and colours:

Clambering roses peep into her chamber,

Jasmine and woodbine, breathe sweet, sweet,

White-necked swallows twittering of Summer,

Fill her with balm.

Waking at dawn, the girl is depicted as innocent, "pure" and "perfect" in the poet’s imagination, and beautiful as a flower. "Beauteous she looks! like a white water-lily / . . . clothed from neck to ankle / In her long nightgown, sweet as boughs of May, / Beauteous she looks! like a tall garden lily / . . . And the gold sun wakes." The promise of new life in spring is indicated by birds nesting, and the poet welcomes the season of new growth: "Then come merry April with all thy birds and beauties! / . . . With thy budding leafage and fresh green pastures; / . . . Come merry month of the cuckoo and the violet!" He anticipates a new beginning for himself and a bride in the final line of the poem: "Bring her to my arms on the first May night" (574-75).

As "Song in the Songless" suggests, such sensory experiences, and the longings they provoked, remained with the poet throughout, even when he was no longer able to enjoy them at first hand. Indeed, the power of others' acute observations could still provoke such responses in him. Aged 74, he wrote to Wilkinson Sherren, author of Wessex of Romance (1902), expressing gratitude for the gift of his book, which would provide a "stimulant to imagination" for walks which he had not been able to take (Cline 1436).

PART II

Feeling "the winds of March when they do not blow": Close readings from The Ordeal of Richard Feverel

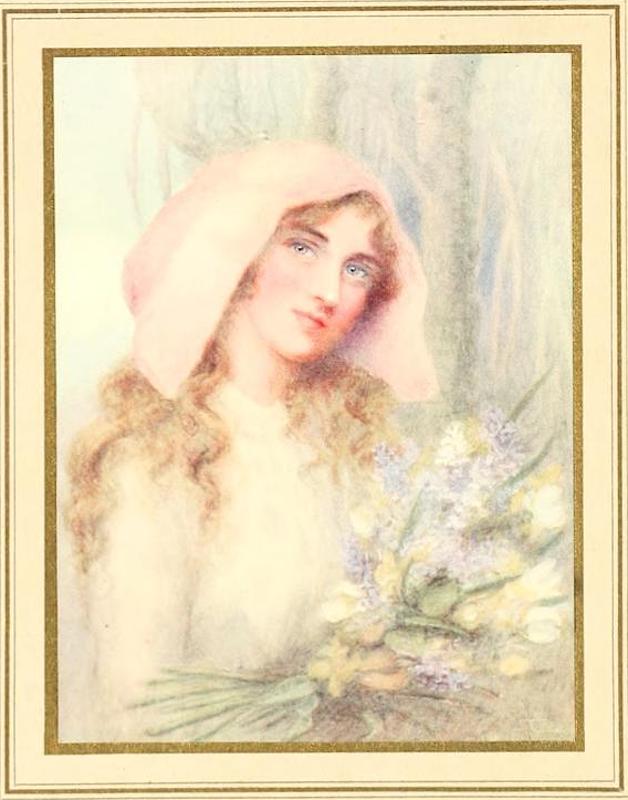

Herbert Bedford's "Lucy" in his depictions of The Heroines of George Meredith (1914).

Natural imagery highlights the intensity of first love in Meredith’s first novel The Ordeal of Richard Feverel, published in 1859, in which the narrator explains his innovatory use of sensory detail in fiction. In his own voice, he recognises the popular appeal of "sensation" fiction, acknowledging that "an audience impatient for blood and glory scorns the stress I am putting on incidents so minute, a picture so little imposing," but suggests that an audience "will come . . . who, as it were, from some slight hint of the straws, will feel the winds of March when they do not blow . . . will see the links of things" (189). In chapter XIV, titled "An Attraction," Meredith links the beauty of nature with that of a girl, as in the poem "Love in the Valley," using sights, sounds, scents, and colours to share the sensory experience with readers. Richard Feverel, whose childhood has been restricted by his father, has reached the "Magnetic Age . . . of violent attractions" (83). While he is rowing vigorously in his boat, with a sense of "a secret abroad" in the woods, waters and winds, he beholds "the sweet vision" of Lucy (93,97), who is oblivious to his presence and is depicted as young, innocent and sensuous, part of the pastoral setting:

Above green-flashing plunges of a weir, and shaken by the thunder below, lilies, golden and white, were swaying at anchor among the reeds. Meadow-sweet hung from the banks thick with weed and trailing bramble, and there also hung a daughter of earth . . . Across her shoulders, and behind, flowed large loose curls, brown in shadow, almost golden where the ray touched them . . . her lips were stained . . . regaling on dewberries. [96]

Lucy’s "dainty" act of eating them is feminine and erotic:

The little skylark went up above her, all song . . . from a dewy copse dark over her nodding hat the blackbird fluted, calling to her with thrice mellow note: the kingfisher flashed emerald out of green osiers: a bow-winged heron travelled aloft, seeking solitude . . . Surrounded by the green shaven meadows, the pastoral summer buzz, the weir-fall’s thundering white, amid the breath and beauty of wild flowers, she was a bit of lovely human life in a fair setting: a terrible attraction.

The effect of the "sweet vision" on Richard is heightened by the contrast with his restricted upbringing, and Meredith conveys sexual tension as the young couple become aware of each other’s presence: "Stiller and stiller grew nature, as at the meeting of two electric clouds" (96-97).

Richard and Lucy marry, but Richard remains immature in forming relationships and making decisions. A significant stage of his development is described towards the end of the novel in chapter XLII, "Nature Speaks," as Richard learns of the birth of his son. His rite of passage from husband to father is represented by a night walk in the forest, and his liminal state of mind is reflected in the description of the stillness before a storm. "The moon was surpassingly bright: the summer air heavy and still." Walking rapidly into the forest, "the leaves on the trees brushed his cheeks; the dead leaves heaped in the dells noised to his feet" (423). "By the log of an ancient tree . . . he halted," discovering a dog which accompanies him, "and both were silent in the forest-silence.... An oppressive slumber hung about the forest-branches. In the dells and on the heights was the same dead heat. Here where the brook tinkled it was . . . metallic, and without the spirit of water. . . . The breathless silence was significant. . . . Now and then a large white night-moth flitted through the dusk of the forest." Pausing to rest on "grey topless ruins set in nettles and rank grass-blades," Richard "sat as a part of the ruins," without thought or energy. He did not observe the "long ripples of silver cloud" which were "the van of a tempest . . . or the leaves beginning to chatter" but continued to walk. "The ground began to dip; he lost sight of the sky" (424-25).

The effect of the storm is described in vivid images, which reflect the awakening of Richard’s senses, as he moves towards a harmony of body, mind and spirit, in a closer relationship with nature.

Then heavy thunder-drops struck his cheek, the leaves were singing, the earth breathed. . . . All at once the thunder spoke. . . . Up started the whole forest in violet fire . . . white thrusts of light were darted from the sky, . . . Then a shrill song roused in the leaves and the herbage. Prolonged and louder it sounded, as deeper and heavier the deluge pressed . . . .the grateful breath of the weeds was refreshing. . . . He fancied he smelt meadow-sweet . . . stretched out his hand to feel for the flower . . . encountered something warm . . . a tiny leveret. [425]

The rain was now "steady; from every tree a fountain poured" and Richard’s mind has become "cool and easy." Experiencing "a strange sensation . . . purely physical . . . wonderfully thrilling," produced by the leveret’s "small rough tongue going over and over the palm of his hand . . . his heart was touched." Then "A pale grey light on the skirts of the flying tempest displayed the dawn" and Richard "felt in his heart the cry of his child, his darling’s touch" (p.426). He "looked out from his trance on the breathing world, the small birds hopped and chirped: warm fresh sunlight was over all the hills." Richard emerges from the forest "under a spacious morning sky" and in a new state of mind (427). No one reading these passages can resist being carried along by Richard's sensory experiences, or fail to share his renewed hope as emerges from them.

"Mr Meredith is a poet - in prose": Close reading from The Egoist

John C. Wallis's frontispiece to the American revised edition shows Willoughby sauntering in his manicured gardens, with a downcast Clara by his side.

Natural imagery and impressionistic descriptions are also used by Meredith as a means of characterisation in his later novel, The Egoist, published in 1879, which anticipates the "New Woman" fiction of the 1890s. Clara Middleton is a naïve nineteen-year-old girl, betrothed to Sir Willoughby Patterne by "consent" rather than choice. She is portrayed as being physically active as well as feminine, demonstrating the freedom of natural behaviour, and challenging the socially constructed perception of women. Clara "had a spirit with a natural love of liberty, and required the next thing to liberty, spaciousness, if she was to own allegiance’ (51-52), whereas her fiancé ("the egoist") is happiest closetted in his laboratory within the "fortress" of his estate, and is ill-at-ease in nature. Clara’s need for connection with the natural world is evident as, we are told, nature provides "a background to her joyful optimism," and she thinks that "If Willoughby would open his heart to nature, he would be relieved of his wretched opinion of the world" (217). Clara prefers "fields, commons" and the honesty of ugliness, to the overwhelming prettiness of the "parks of rich people" (183). Thus, when ten-year-old Crossjay leaves "a big bunch of wild-flowers" for Clara, which are perceived as "vulgar weeds . . . about to be dismissed to the dust-heap by the great officials of the household," Clara is "very pleased’ with his "presentation-bouquet," recognising the combined efforts of Crossjay and Laetitia Dale "in the disposition of the rings of colour, red campion and anemone, cowslip and speedwell, primroses and wood-hyacinths; and . . . a branch bearing thick white blossom’ which is identified as the wild cherry (89).

The physical description of Clara and her clothing is impressionistic, and a contemporary reviewer acknowledged that the "select" circle of his readers "know that Mr Meredith is a poet - in prose" (Pattison, Academy (1883), qtd. in Williams 249). Meredith’s perceptive character, Vernon Whitford, says that Clara "gives you an idea of the Mountain Echo" (37), and the narrator offers "some suggestion of her face" compared to "Aspens imaged in water, waiting for the breeze," as well as referring to her "winter-beechwood hair" (46). When Clara is "chatting and laughing" with Colonel de Craye and Crossjay, the narrator describes her as "a sight to set the woodland dancing, and turn the heads of the town." Although her "irregular features" are unlikely to please "a jury of art-critics . . . her figure and her walking would have won her any praises," and her dress is "cunning to embrace the shape and flutter loose about it, in the spirit of a Summer’s day" (200,201). Clara’s clothing allows for freedom of movement, revealing the natural shape of the girl’s body, conventionally concealed beneath artificial fashions of the period, and the sensuality of her movement is compared to a tree blown in the wind: "See the silver birch in a breeze: here it swells, there it scatters . . . and now gives the glimpse and shine of the white stem’s line within." Wearing a fichu and dress of "thin white muslin . . . trimmed with deep rose" she "carried a grey-silk parasol, traced at the borders with green creepers," with "a length of trailing ivy" across her arm and "a bunch of the first long grasses" in her hand. "These hues of red rose and green and pale green, ruffled and pouted in the billowy white of the dress" (201). The focus on colour and foliage confirms that Clara is very much part of the natural world.

Conclusion: "Thousand eyeballs under hoods / Have you by the hair": reading as a sensory experience

Meredith's acute awareness of the physical sensation evoked by a book is expressed in The Ordeal of Richard Feverel, in which Mrs Berry’s bridal gift to Richard and Lucy is described in terms of sight, scent and touch. It is "a much-used, dog-leaved, steamy, greasy book" of recipes (253), which represents many years of use, and her philosophy that "Kissing don’t last: cookery do!" (227). Through his own books, Meredith offers readers his sensitive observation of the world around him, and shares his love of nature and his understanding of human situations and emotional reactions, anticipating that readers will be stimulated to respond by using their own senses and imagination. As suggested above, natural imagery and impressionistic descriptions in his writing make reading his work a sensory experience. One of the best examples of this must be in "The Woods of Westermain," when he so succinctly conveys the sense of being watched, and the feeling of apprehension — of hair actually standing on end — in just nine words: "Thousand eyeballs under hoods / Have you by the hair" (193).

As for Meredith's use of poetry in prose, that this was a subtle means of encouraging his "audience" to "feel the winds of March," in contrast to the mere transient excitement offered by much contemporary fiction, was recognised at the time. Reviewing Sandra Belloni in 1864, for instance, Geraldine Jewsbury declares that "Our sensibilities are fatigued by the strong sensation novels we have daily to encounter." Describing an emotional reaction to Meredith’s novel, Jewsbury asserts that Emilia’s father breaking his violin "affects the reader like the killing of a living creature," and that the "snares and pitfalls" of Emilia’s story "make the reader tremble" (qtd. in Williams, 111-12).

At least among those best attuned to it, then, the physical and mental response to his sensory writing was much as Meredith anticipated. Following publication of The Egoist in 1879, the poet W.E. Henley noted that Meredith is "an ardent student of character," and that "he has a poet’s imagination and he is a quick observer" (qtd. in Williams, pp.206, 215). Quoting a paragraph from The Egoist, the poet and critic Richard Le Gallienne wondered "if any honest male ever read this passage without its catching his breath, and making him put down the volume for a moment or two’s thought - to take it up, perchance, a different man. Here, in a phrase from which one reels sick as from a blow . . . here we first realise what this egoism is" (21). Recognising the potential for egoism in everyone, this comment represents exactly the kind of physical and mental response to his writing that Meredith sought to produce.

Bibliography

Note: All poetry quotations come from Trevelyan’s 1912 complete edition of Meredith’s poems in one volume, with notes (The Poetical Works of George Meredith).

Cline, C. L. The Letters of George Meredith, edited in three volumes. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1970.

Ellis, S. M. George Meredith: His Life and Friends in Relation to his Work. London: Grant Richards, 1920.

Hammerton, J. A. George Meredith in Anecdote and Criticism. London: Grant Richards, 1909.

Le Gallienne, Richard. George Meredith: Some Characteristics. London: John Lane, 1905.

Meredith, George. The Ordeal of Richard Feverel. 1913. London: Constable, 1913.

_____. Sandra Belloni, originally Emilia in England. 1864. London: Constable, 1914.

_____. The Adventures of Harry Richmond. 1871. London: Constable & Company, 1909.

Meredith, George.The Egoist. 1879. London: Constable, 1915.

Mitchell, Rebecca N, and Benford, Criscillia, eds. George Meredith: Modern Love and Poems of the English Roadside, with Poems and Ballads. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2012.

Sharp, William. "Literary Geography. London": in The Pall Mall Magazine, 1904.

Stevenson, Lionel. The Ordeal of George Meredith. New York: Scribner’s, 1953.

Trevelyan, G. M., ed. The Poetical Works of George Meredith, with notes by G M Trevelyan. London: Constable, 1912.

Williams, Ioan, ed. Meredith: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1971.

Created 20 September 2025