July 1843 through August 1844: Instalments Eighteen and Nineteen (Chapters LXXV through LXXXI)

In the eighteenth instalment, Tom begs to be put ashore by the Jersey smugglers of French brandy when learns that the cutter is off the Wicklow headland on their second morning out of Falaise de Biville in Normandy. Breakfasting with a fisherman and his family in their seaside cottage, Tom endeavours to catch up with the affairs of his native land after so many years away. In the eyes of the peasantry the oppressors are no longer the English per se, but the Anglo-Irish landlords. For a young man in top physical form, the forty kilometre walk from the easternmost point in Ireland to its principal city proves no challenge. When he enters the coffee room in Miley's Hotel, Dublin (seen in the background of Phiz's monthly illustration The Newsvender in Chapter LXVII, "A Character of 'Old Dublin'"), Tom is struck by the absence of political factions and contentious debate on national affairs. He is unaware of what has wrought the social transformation upon the place, namely the 1801 Act of Union, by which Ireland has lost its own parliament, and is now governed from Westminster, with the participation of one hundred elected Irish Members of Parliament — all of them Anglicans (members of the Church of Ireland).

In spite of is foreign appearance, Tom settles into to the society of the coffee room, only to be accosted by a bailiff (for such he is), who seems to know Tom by name, and indeed has a warrant for his arrest. This he promptly fills in, and demands bail; however, Tom is without either friends or relatives in Dublin, and therefore can provide no such surety. The timely intervention of a well-mannered stranger with whom he had briefly interacted in street results in Mr. Roche's relenting, and Tom's being permitted to remain in the hotel overnight.

Plot complications attendant upon Tom's return to Ireland now arise from Tom's apparently having been implicated in the attempted murder of Major Crofts all those years before at the Dublin barracks of the 45th Regiment, in Major Bubbleton's rooms, even though the assailant, Darby, was merely protecting Tom from Crofts. Consequently, a warrant is still out against Tom. When Tom visits Dublin Castle, however, M'Dougall, the kindly stranger whom he met the day before at the hotel, offers to represent him. When Major Barton interrogates Tom, he mentions that there is a general amnesty for which Tom might apply, and that a moderate bail will be all that is expected of Tom since he in no way is an agent of the French government, and has never engaged while a French officer in a battle with British forces. Thus, Tom approaches attorney Basset's office to get in contact with his brother, George, who is certain to go his bail. From the clerks in the office Tom learns that his older brother has died of a fever "after some debauch at Oxford" (278). When Basset returns from court, he tries to buy Tom off with a peculiar arrangement: if Tom will swear that Captain Burke has died abroad, he will give him one hundred pounds. Quickly Tom discovers that Basset's intention is to effect the inheritance of a distant next-of-kin, Sir Montague Crofts. Even though Darby, the only person who could attest to Tom's innocence in the felony assault, has been transported for life, Tom refuses Basset's offer. At this moment, Major Barton arrives at Basset's office, and has two agents apprehend Tom and take him off to Newgate. The charge is felony assault on then-Captain Montague Crofts, "to assassinate an officer in his majesty's service" (280) all those years before, when Tom indeed was a minor. Thus matters stand at the end of Chapter LXXX, "An Unforeseen Evil," in the August 1844 instalment.

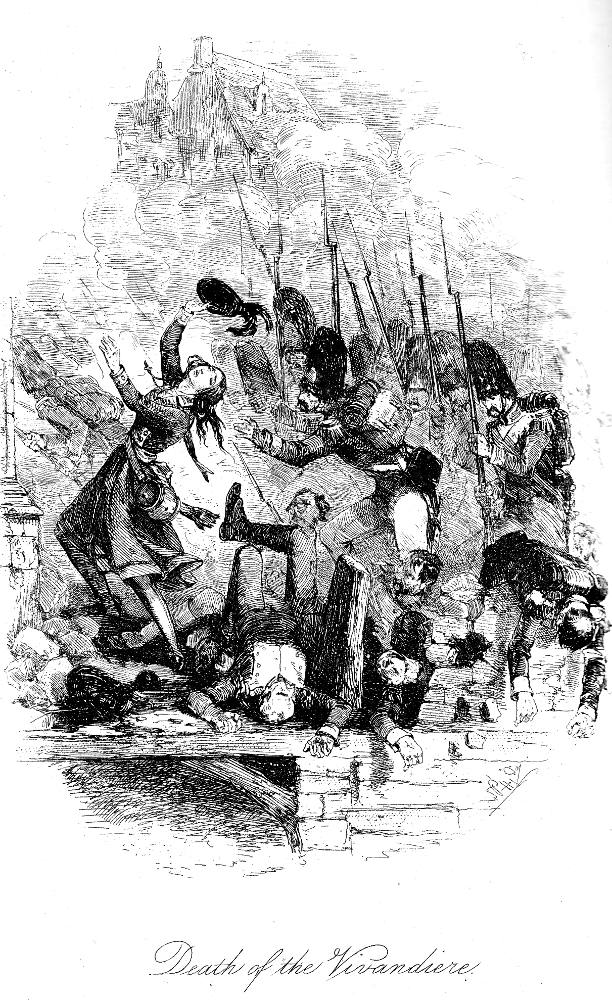

As the second illustration for the August 1844 instalment announced to Lever's serial readers, Darby the Blast now providentially turns up to exonerate Tom of the charge of attempted murder that Crofts has levelled against him. The illustration at the head of the nineteenth monthly number anticipates the courtroom scene which winds up the monthly instalment. Darby does not merely exonerate Tom of the crime of the attempted murder of Sir Montague Crofts; he completely explodes the identity of the supposed victim by revealing that Crofts' legitimate brother, Daniel Fortescue, is very much alive — and, indeed, is in the gallery watching the proceedings. Thus Darby shifts attention away from the French bank draft (Payez au porteur la somme de deux mille livres.) that Tom had offered Crofts in the George's street barracks as payment for Bubbleton's gambling debt, an important strategic move to shift attention from Crofts' lawyer's implication that Tom all those years ago was both a Nationalist agitator and a French agent. Tom had thought that Darby picked up the bank draft, but in fact he had acquired Crofts' notebook that contained evidence of his duplicity in the Nationalists' enlisting Fortescue as their dupe. Serving in the British Navy, Fortescue had in fact helped Darby escape from Australia (where he had been transported as a Nationalist ring-leader), and is responsible for his fortuitously returning to Dublin just in time to corroborate Tom's version of events. Having exonerated Tom, Fortescue barely has time to shake his hand before Major Barton has Fortescue arrested on charges stemming from the massacre at Kilmacshogue. As Tom passes out of the courthouse, attorney Basset salutes him as "Mr. Burke of Cromore," heir to an estate of a thousand pounds a year. Clearly Basset wishes to retain his position as legal counsel for the estate. In exchange, the devious attorney promises to have Darby at liberty within forty-eight hours. Tom is cheered by ordinary Dubliners back to his hotel.

Final Instalment, September 1843: Chapters LXXXII-LXXXVI & "A Parting Word."

The concluding chapter of the August instalment has "averted the peril" of Tom's being imprisoned for Crofts' attempted murder. In the opening chapter of the final instalment, "A Hasty Resolution," Tom, having suddenly come into great wealth, arranges pardons for both Darby M'Keown and Daniel Fortescue. He attempts to fulfill the duties of the owner of an Irish estate by dealing with his tenants generously. Having tried to enter local society but met with rebuffs from his Tory neighbours, and having tried to indulge himself as a sportsman, Tom aquiesces in the mistrust of both his peasantry and his fellow land-owners. And then his mania for word of France’s military achievements and setbacks is inflamed by the news of Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow after the disastrous fire of 14 to 18 September 1812 which all but destroyed the city and forced Napoleon's retreat. Aside from his close relationship with Darby, Tom has become a recluse, and is suffering from what modern readers would recognize as depression. As the chapter closes, Tom is determined to come to rescue of his Emperor, and at Skerries offers one hundred pounds to any fishing captain who will land him in Holland or France: "Ere half an hour I was on board" (315).

In Chapter LXXXIIII, "The Last Campaign," Tom returns to France in time to see the death of Minette and the fall of Napoleon. Suffering from a depression brought on by having no sense of purpose or place in Irish society, Tom charters a fishing-smack to get him to the French coast. He then hastens towards eastern France, where he meets veterans who have re-enrolled themselves. Conscript armies made up of mere adolescents now crowd the highways, but they lack the old spirit of conquest and adventure. At Verviers, where Tom volunteers to lead a ragtag cavalry brigade for General Letort, he regains his officer's commission by offering to pay the expenses that the commissariate has failed to advance for the campaign: twenty thousand francs (which he has with him in the form of one thousand golden guineas). Encountering his old friend from the Polytechnic, Colonel Tascher, Tom assumes command of the Tenth Hussars, whom he leads into combat at the village of La Giberie against a Russian battery.

The outcome of the battle for the bridge at Montereau is decided not by hussars, cuirassiers, or even the Old Guard, but is stalled by terrific charges of grapeshot from the batteries on both sides. Napoleon's favourite manoeuvre of cavalry and infantry supported by artillery seems to be failing as Tom discovers the lifeless body of General Auvergne, cut through by grapeshot, in a pile of corpses, sword still in hand, as night falls. Marie de Meudon is now a widow, but Tom seems motivated more by a desire to win Napoleon's Cross of the Legion of Honour than to survive to marry the young widow, as he presses forward to ignite the petard on the bridge. He is successful, making it possible for the Grenadiers to storm across the bridge, but is shot as he tries to escape the force of the explosion. Suddenly Tom awakes to find himself comforted by Minette's flask and caring hands. However, when she sees Marie's miniature, her sense of unrequited love compels her to stand and wave on the charging veterans. She falls to a marksman's bullet. At her funeral, Pioche kisses her corpse, then collapses on the turf beside her grave, dead from the shock, and is interred with her in the concluding lines of Chapter LXXXIV, "The Bridge of Montereau." For his foolhardy valour and sheer dedication to Napoleon, Tom is promoted to the rank of General and given his own brigade.

The final two chapters constitute the dénouément as Lever winds up Tom's account of the fall of Napoleon and the narrator's return to Ireland. For two months he lies recuperating from his wounds at the palace of Fontainebleau, nearly dying of fever twice. Despite the victories at Champ-Aubert, Montirail, and Montereau, Napoleon is suffering defections and even treasonous rebellion. In the night in the gardens at Fontainebleau Tom encounters Napoleon, and the two bid each other a sad farewell. "The Empire was ended, and the Emperor, the mighty genius who created it, on his way to exile" (Chapter LXXXV, "Fontainebleau," 339). The Parisians, their Emperor departed for Elba, fawn upon their arrogant conquerors, the Russians and the Prussians, who now invest the capital. And the palace of the Tuileries is now occupied by a Bourbon, and is the scene of royalist fêtes and balls. One evening shortly after the restoration, while walking to recover his health Tom is confronted by a mob on the Boulevard Montmartre as a military parade advances along the thoroughfare. Following these Napoleonic regiments (now wearing the white rather than the tricolour cockade) are old cavaliers wearing the order of St. Louis, devout monarchists. Tom in his uniform stands out as a Napoleonist amidst the crowd cheering "Vive le Roi!" Suddenly he finds himself an object ridicule, and is about to be assaulted when a royalist colonel mounted on a magnificent white charger intervenes. Thus, Tom and Henri de Beauvais are reunited, friends once again. But the incident warns Tom that it is high time he left France.

And here the trajectory of Lever's story emulates that of his model, Sir Walter Scott's Waverley; or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since (the Scots historical novel begun in 1805, but not published until 1814, coincidentally the very year in which Napoleon was compelled by the Allied powers to step down and go into exile). Just as the collapse of the Jacobite cause prompts Edward Waverley to abandon the soldier's life for that of an agricultural landlord, so the restoration of the Bourbons under Louis XVIII on 3 May 1814 compels Tom Burke to abandon his Napoleonic adventures and return home to his estate. The question uppermost in serial readers' minds, of course, must have been, "With the Vivandière dead and buried, will Tom marry Marie d'Auvergne (née De Meudon), recently widowed ("who lived in all my thoughts, and, unknown to myself, formed the mainspring of all my actions")? Tom's determination to leave is shaken by an offer from De Beauvais, the rank of General in the reorganized armed forces of Louis XVIII. He declines the tempting offer because he remains Napoleon's soldier, even though the Marshals Ney, Soult, Augereau, Macdonald, and Marmont have all gone over to the Bourbons. In De Beauvais own words, "the Empire was a vision, and like a dream it has passed away. Where there is no cause there can be no fealty" (344). But Tom refuses to see the Count d'Artois about a senior posting in the new army.

Thus, Lever must provide a final interview with Marie de Meudon in order to maintain the suspense to the final lines of the novel. In parting, then, De Beauvais delivers a note which proves to be a request that Tom visit Marie at the Hộtel de Grammont that very evening. Significantly, Lever has not suggested this scene as the basis for an illustration, for such an engraving at the head of the last instalment would have perhaps let the cat out of the bag, so to speak. "Will she, with her royalist inclinations, accept the marriage proposal of an avowed Napoleonist?" Tom wonders as he speculates that this will be their last meeting. He need not have feared: he proposes, she accepts, and they leave France together, although their destination remains a matter for the reader's speculation.

I can but remember the bursting feeling of my bosom, as she placed her hand in mine, and said, "It is yours." (347).

Further Information

- Charles Lever's Fourth Novel, Tom Burke of "Ours" (February 1843 — September 1844)

- Instalment-by-instalment Synopsis of the Novel's Plot and Characters: Lever's Tom Burke of "Ours" (February through April 1843)

- Instalment-by-instalment Synopsis of the Novel's Plot and Characters: Lever's Tom Burke of "Ours" (May through August 1843)

- Instalment-by-instalment Synopsis of the Novel's Plot and Characters for Tom Burke's Adventures in France: Lever's Tom Burke of "Ours" (September 1843 through June 1844)

- Phiz and Lever: A Fascination with Napoleon (1840-43; seven plates)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the images, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Lever, Charles. Tom Burke of "Ours." Dublin: William Curry, Jun., 1844. Illustrated by H. K. Browne. Rpt. London: Chapman and Hall, 1865. Serialised February 1843 through September 1844 in twenty parts. 2 vols.

Lever, Charles. Tom Burke of "Ours." Illustrated by Phiz [Hablột Knight Browne]. Novels and Romances of Charles Lever. Vols. I and II. In two volumes. Dublin: William Curry, 1844, and London: Chapman and Hall, 1865, Rpt. Boston: Little, Brown, 1907. Project Gutenberg. Last Updated: 27 February 2018.

Stevenson, Lionel. Dr. Quicksilver: The Life of Charles Lever. London: Chapman and Hall, 1939.

Sutherland, John. "Tom Burke of "Ours"." The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford U. P., 1989. P. 632.

Created 28 November 2023 Last updated 5 December 2023