ollowing his long series in the Leisure Hour Jerdan started a new series for the same magazine in February 1868 called ‘Characteristic Letters’, with the tag line “Communicated by the author of ‘Men I Have Known’.” His column appeared once a month and the first instalment, on 1 February, opened with the challenging question: “Why should a man ‘be dead a hundred years’ – by which time nobody cares much about him – before it is reckoned quite timely to illustrate his character by publishing any of his correspondence? ... a single letter, or a single expression in a letter, has often marked a striking trait in the character of the writer, which might furnish a key to the right interpretation of much of his outward life and action”. Jerdan claimed that he had selected from his mass of papers those which would not “hurt a feeling of the living or violate a sanctuary of the dead”. With a ring of false modesty, he assured readers that he had to print a complete letter even though this could mean the inclusion of “passages complimentary to myself”, in his former capacity as editor of the Literary Gazette. The chosen letters represented a wide range of correspondents, and Jerdan alternated the letters with brief personal memories, anecdotes or observations about each correspondent. His first subject was the scientist Michael Faraday, whose letter informing Jerdan that the Royal Institution had chosen him as its first Chair of Chemistry was reprinted here. Jerdan’s second subject in this initial column was Hans Christian Andersen, whose warm letters of 1847-48 Jerdan was proud to include.

ollowing his long series in the Leisure Hour Jerdan started a new series for the same magazine in February 1868 called ‘Characteristic Letters’, with the tag line “Communicated by the author of ‘Men I Have Known’.” His column appeared once a month and the first instalment, on 1 February, opened with the challenging question: “Why should a man ‘be dead a hundred years’ – by which time nobody cares much about him – before it is reckoned quite timely to illustrate his character by publishing any of his correspondence? ... a single letter, or a single expression in a letter, has often marked a striking trait in the character of the writer, which might furnish a key to the right interpretation of much of his outward life and action”. Jerdan claimed that he had selected from his mass of papers those which would not “hurt a feeling of the living or violate a sanctuary of the dead”. With a ring of false modesty, he assured readers that he had to print a complete letter even though this could mean the inclusion of “passages complimentary to myself”, in his former capacity as editor of the Literary Gazette. The chosen letters represented a wide range of correspondents, and Jerdan alternated the letters with brief personal memories, anecdotes or observations about each correspondent. His first subject was the scientist Michael Faraday, whose letter informing Jerdan that the Royal Institution had chosen him as its first Chair of Chemistry was reprinted here. Jerdan’s second subject in this initial column was Hans Christian Andersen, whose warm letters of 1847-48 Jerdan was proud to include.

Punch's tribute to Hans Christian Andersen on 3 January 1857.

Despite being overlooked on the occasion of Andersen’s last visit to England in 1857, Jerdan wrote to him in February 1868, enclosing a copy of the Leisure Hour featuring his article on Andersen’s letters. His accompanying note, kept at the Hans Christian Andersen Center, University of Southern Denmark, was friendly and personal:

I dare say you will be surprized to see a letter from One you left so old a personage that you could hardly expect to hear from him after so long a period of time had elapsed. Yet here I am in the breathing world, still, though verging on my 86th birthday, and still remembering with true-hearted feelings every circumstance which united us in mutual regard and esteem during your visit to London – to London, wonderfully, and, to me, sadly changed since you were here.

But why am I induced to you now. I hope you will receive with this the monthly part of a periodical of vast circulation, The Leisure Hour, to which I have ventured to contribute a memorial of our friendly intercourse. I trust you will rather be pleased with it, than blame it as a liberty with private correspondence. Tell me?!

Do you recollect the sweet pretty mother whom you enchanted with a Poet’s kiss? She has been eleven years in her grave, leaving a fine boy of that age – the one knowing nothing of her gift, and the other nothing of his loss. The little girl whom you also kissed, declares she remembers it perfectly well, and consequently reads your Tales at our nightly fireside with important emphasis, as if one of the initiated. These Tales I enjoy as much as ever, though I observe errors in translations which do not do justice to the exquisite touches of the original, nor the finest of spirit and nature which only a few congenial souls can truly appreciate. Still, there is enough left for great popularity, and I see editions everywhere advertized by the “Trade”. One of these, Routledge, borrowed from me the portrait engraving of yourself which you gave me with an inscription of praise and cordial affection, which I valued beyond prize. And it is most unpardonable – my picture is mislaid or lost – “strict search” is to be made for it! Confound the Trade and all who belong to it. I am on tenter hooks, as the saying is, and the wall of my little room despoiled, vacant, deplorable.

Might I hope for the delight of a letter from you? If? It would, my dear friend, make me exceedingly happy.

The “sweet pretty mother”, Mary Maxwell, had in fact died in 1862, only six years previously, although to Jerdan it may have seemed like eleven. Her last child, as far as is known, was born in 1855, but from Jerdan’s comment there seems to have been a later birth from which she died. No evidence for this “fine boy” has come to light.

The March issue of Leisure Hour reprinted letters from Benjamin Haydon, painter of vast pictures, thanking Jerdan for his kindness and sending a drawing in appreciation, with another letter from the time in 1846 when the Egyptian Hall made hundreds of pounds by exhibiting the midget, General Tomb Thumb, whilst takings for Haydon’s own exhibition did not cover the room rent. These, said Jerdan, were examples of his opening claim, illuminating the true character of a man in a few strokes of the pen. There was a correspondent however, Jerdan admitted, who could not be delineated were all of his letters to be collected. His reference was to the volatile Dr Maginn, and the letters he chose to print were those from way back in 1821 when he first met the young Irishman. One of these quoted, “showed a bit of the temper of my friend”; having seen a copy of the Literary Gazette, Maginn confronted Jerdan with, “Do you intend to list yourself in the business of libelling me, or copying those who do? I ask merely for information; because if such be your design, it is a game at which two can play, and I hate being under an obligation to any man which I do not intend to return.” Sorting through Maginn’s letters must have brought back many bitter, as well as enjoyable, memories to Jerdan, especially their rivalry for Landon’s affections. Jerdan made no reference to Maginn’s slide into drink, destitution and early death, commenting only, “His eccentricity was a constant source of pleasantry to friends and no heinous offence to enemies.”

Some of Jerdan’s ‘Characteristic Letters’ throughout the year struggle to fit into his claim of illuminating character and have more the feel of filling his column inches, although this was definitely not the case with his April contribution, stirred by the appearance in January’s Quarterly Review of Lockhart’s Life of Sir Walter Scott. Jerdan did not know who the Quarterly’s reviewer was, but thought that “he is one of the very few remaining who are conversant with the facts and competent to handle the subject.” Saying how Scott, eleven years his senior, had lived in the same landscape, and attended the same school as he had, and how they had both collected ballads, Jerdan identified closely with Scott. He purported to be “amused” at their similarities and yet acknowledged their great difference in the pursuit of literature. Jerdan had displeased Scott once in reviewing a late novel, he recalled, and Scott evaded Jerdan’s visit to him at Abbotsford, although friendly at a subsequent meeting. “I felt some satisfaction in having a sad posthumous revenge”, wrote Jerdan, “by being one on the sub-committee of management for preserving Abbotsford in the family and by my zeal in adding a considerable amount to the subscription.” He paired letters from Scott with some from James Ballantyne, and gave a brief note on John Ballantyne, from whom he had no letters to print.

John Ballantyne, Albumen carte-de-visite by James Good Tunny, from the 1860s. © National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG Ax14908), reproduced here by kind permission.

On 1 May Jerdan chose the letter he had received from Wordsworth irritably rejecting his suggestion of recording an imminent tour of the continent for publication in the Literary Gazette. The poet scolded, “Periodical writing, in order to strike, must be ambitious, and this style is, I think, in the record of tours and travels, intolerable, or at any rate the worst that can be chosen.” Reinforcing his theme of poets, Jerdan printed James Hogg’s letter of December 1832 discussing inter alia, his desire to marry Mary Jerdan to his nephew, together with those of two more minor figures.

Francis Bennoch, 1812-1890 by William Ridgway after Alexander Johnston.

Courtesy of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

In preparing for this series, Jerdan, in a note of 24 May 1868, requisitioned some material from his old friend Francis Bennoch, accepting his offer for letters from Mary Russell Mitford (MsL J55bA, Iowa). Sympathising with his friend’s current troubles, Jerdan told him how, although he could “bear my own sickness and troubles as well as may be,” he could not so well endure those of a friend who had given him so much sympathy and assistance in times of want. He had heard from “all the Australian boys ... the Queenslanders have a hard and rough fight with that new world”, he confided to Bennoch. A subsequent letter, three weeks later, returned one of the four letters of Mitford’s, and asked Bennoch whether he had seen the column on Haydon, as he had been alluded to. “The Sculptor has cut me dead, though I am still alive,” he complained, possibly referring to Durham. “Strange it is. I was his earnest friend in his early life – we have been friends through not a few intervening years, and he has been the friend of my decline. But I have not heard from him for months ... I fear I have lived too long and tired out remembrance of auld lang syne in some instances!” (13 June 1868, MsL J55bA, Iowa). This neglect, or perceived neglect, of old friends hurt Jerdan deeply, especially in the many cases where he had been the means by which the writer or artist came into public recognition. But he was very old now, living far from Town and of no more practical use in promoting his friends. As he told Bennoch, “it is a way of the world, but I did not expect it in that quarter.” When Jerdan returned Mitford’s letters to Bennoch he explained that “The Leisure Hour does not afford much space or honorarium, but it is all very well towards the pot-boiling as far as it goes.” He was enjoying old copies of a magazine, the Once a Week (published between 1859-1865) which had been lent to him, and asked Bennoch to identify his contributions. Jerdan was feeling better and thought he may even visit London again. “But uncertainty rather predominate after 86, and when the bad bits happen, I can only reconcile myself to a quiet look up at Mr. Auctioneer Death’s uplifted hammer and bide to see whether the lot is put off unsold, or it is to come down “Going – Gone!” and I shall be no more.”

Before the hammer fell, however, Jerdan had more ‘Characteristic Letters’ to send to the Leisure Hour. In June he mentioned the Irish bard James Sheridan Knowles, and the novelist and poet Barbara Hofland, but the greater part of the issue of 1 June was reserved for his great friend of many years Crofton Croker, even though Croker had died before the rift between them could be mended. Celebrating Croker’s writings about his homeland, Ireland, Jerdan noted sadly, “He was taken from us before Ireland had fallen upon the evil days of which we hear so much”. What would Croker have thought now, he wondered, “Where are the Irish characteristics – the good humour, the sportiveness, the nonchalance, the open-heartedness, and the brave endurance of hardship or misfortune.” Jerdan mused that he hoped the visit of the Prince and Princess of Wales would be the harbinger of better days for Ireland – he would have been appalled to know that it would take more than a hundred and thirty years before this could happen. He shared two of his friend’s letters from 1828, explaining how Croker often “engrafted the pencil on to the pen”, reproducing a drawing Croker had sent to accompany his account of suffering from gout, his left arm in a sling, a nightcap on his head, and hobbling on crutches. The letter was about Literary Gazette matters and then, responding to a note he had received from Jerdan, said, “I really sympathize hand and foot with our poor poetess. The possibility of one who possesses so much innate fire as L.E.L. catching cold, never entered my head.” Even at the expense of reprinting such a trivial note, Jerdan could not resist a reference to Landon. He completed his section on Crofton Croker with an anecdote of the occasion when Mrs Croker and he, knowing friends were seeking a female servant, dressed Crofton Croker up as an applicant. Whilst waiting in the kitchen to be interviewed, he was regaled by the cook with confidential gossip about his prospective employers, painting such an awful picture that he took his leave hastily, before they saw him.

The July column was solely devoted to the Scottish poet Allan Cunningham, and August’s to the “thorough socialist” Edward Forbes, whose comic verse on a British Association meeting at Dudley he printed, together with one of the Anatomy of the Oyster and other examples of Forbes’s offerings. Jerdan coupled this with a smaller section on Edward Jesse who had recently died aged eighty-eight, formerly a Deputy Surveyor of Royal Parks and Palaces. Jerdan recounted the time when he told Jesse that a large and elusive trout had been caught at Windsor by a hook baited with apple blossom; believing him implicitly, Jesse included the story in a book he was currently seeing through the press, until persuaded that Jerdan had hoaxed him and so removed it.

Even though he now had enjoyable work again, Jerdan felt lonely and isolated. On 28 July 1868 he wrote to his long-time friend Thomas Gaspey, wishing they were nearer for a gossip about the old times.

You always refresh my mind, and stir up (as well as rectify) remembrances of the past. My memory, I regret to say gets confused and unsettled; so that a Flapper of Laputa would be very useful. The infirmity of deafness is also a sore drawback and to One who was, you know, a good deal courted for social circles, to be bravely tolerated in a very limited sphere is rather damaging to dear self-conceit.

I cannot but fancy that either you or I might do something profitable in the periodical press; but the young puppies in possession of the kennel do not like the old dogs to intrude.

Sic transit,

Though ever the same Dear Gaspey, Yrs truly [Autograph Letters, Houghton Library, Harvard University.]

In the midst of assembling his letters for the Leisure Hour Jerdan’s family suffered another unexpected bereavement. Writing again to Gaspey on black-bordered paper on 11 August, Jerdan told him, “I have been visited by one of the most dreadful calamities that could have befallen me, in the death of my son in law Irwin, who only at Lady Day entered into the possession of Macready’s property at Elstree” (MsL J55Ac, Iowa). Irwin, aged fifty-eight, had been an Examiner in the Audit Office, and was the husband of Jerdan’s oldest daughter, Frances-Agnes, whom he married in 1844. They had five children and seem to have been in comfortable circumstances. That Jerdan mourned Irwin’s death in the terms he used, that it was a calamity for him, rather than for his daughter and grandchildren, would seem to indicate that Irwin made him an allowance or at least gave him money from time to time, the cessation of which would cause Jerdan much hardship. If Irwin had indeed helped Jerdan out in this way it was generous of him, as it had been his father-in-law’s inability to pay Literary Gazette expenses which had landed Irwin, briefly a partner in the enterprise, in court. Frances-Agnes survived her husband by twenty-three years, dying in 1891 aged eighty-one.

John Murray (1791-1857), engraved by E. F. Finden after H. W. Pickersgill.

Sad as he was at Irwin’s early death, Jerdan still had to produce his column for the Leisure Hour. His September contribution concentrated on two famous literary Scotsmen, John Gibson Lockhart and the publisher John Murray. In introducing the section on Lockhart, Jerdan said that he was glad to have the chance to leave a brief tribute to him, as “few characters have ever been less understood or more misrepresented. But mine is a simple statement: neither an apology nor a defence…” Jerdan set Lockhart into the political context of his time, the high Tory against the opposition Whig press. Even so, Jerdan believed that “the style of criticism at the period referred to was less envenomed than it had previously been, and less dictatorially, and domineeringly offensive than it is generally at the present day.” This was an odd statement from a man who had been personally subjected to venomous abuse in the period he was discussing. Lockhart and he had been on “the most confidential footing for twenty years”, Jerdan claimed, and “a kinder hearted man did not exist.” He printed Murray’s letter of 1825 advising him that Lockhart was appointed editor of the Quarterly Review, a position he held for eighteen years. As son-in-law and biographer of Walter Scott, Lockhart had perforce been involved in the subscription committee to save Scott’s home, Abbotsford, as had Jerdan. In addition to his other work Lockhart had written several works of fiction and Lives of Burns and Napoleon, as well as that of Scott. When he came to John Murray, Jerdan reported how Murray had turned down a proposal Jerdan made to him for a joint venture, claiming that he would make a “restless and fretful partner”, and in another note a “restless and teasing partner”. He remained on good terms with Jerdan, however, as the short note Jerdan printed, confirmed, “I am really yearning to see you…”

In October, Jerdan featured the novelist Mary Russell Mitford, commenting “How different the mental from the physical portrait! The first, a likeness of graceful form and simple beauty; the last, a picture of what Byron rudely called, ‘a dumpy woman’.” He smoothed this with praise of her writing, and mentioned that the Rev. Harness was her literary executor, and Francis Bennoch her friend. Between them they had planned to publish her correspondence and collected works; she had died thirteen years previously, and it was to be hoped that this intended plan would be executed. He included three of her letters to Bennoch, those which he had borrowed earlier in the year, and one of her verses. One letter was in response to Bennoch’s request for a complete list of her works and a few notes on her life, as he knew she was ailing. Her letter was adamantly against writing any sort of autobiography but she did eventually comply with his wishes, and Bennoch was then able to write a brief but accurate biography of her in the >span class="book">Fine Arts Journal. Jerdan made Mary Mitford’s experience of financial difficulties despite being a successful author an opportunity to reiterate the major theme of his Autobiography, by printing her letter asking for his intervention to obtain money due to her for editing the Bijou Almanac after Landon had given it up.

William Blackwood by Sir William Alan, c.1830. Courtesy National Galleries Scotland.

Jerdan’s next subject, in November, was William Blackwood, publisher of Maga in Edinburgh, which started at the same time as Jerdan joined the Literary Gazette. His introduction contemplated the nature of publishers in general, arguing against a current view which saw them as patrons of literature; instead, he believed that “A publisher, educated and endued with the rare gifts of good and sound judgment, who superadds the management of a magazine or periodical to his ordinary business, is in a position peculiarly favourable to be of use to literary aspirants and to promote the best educational interests of the country”. Blackwood, ‘Old Ebony’, he said, was just this type of publisher. Jerdan listed the famous writers whom Blackwood had nurtured in their youth; he abstained, he said, from noticing questions of acrimony, lampooning and so on, levelled against Maga: “much of it was the language common to all parties in those days of ‘pot and kettle’, when people were really more in earnest than they are now. We gladly acknowledge a better tone in the press, and that there are far fewer outbursts of foul words, misrepresentations, and violence. For this we must be thankful.” Jerdan’s analysis here of the difference between the acrimony common in days gone by and his present day, is in contrast to his analysis of the same subject in his piece on Lockhart, where he opined that the earlier press had been less “dictatorially and domineeringly offensive” than at the present day. Returning to the man, however, Jerdan noted that for Blackwood, his work was his hobby, “It was not mere trade”. Jerdan illustrated this by selecting three brief business letters asking or thanking Jerdan for help in promoting a friend and a fourth, which Jerdan called “rather curious” concerning the Edinburgh Review. From the hundreds and hundreds of letters Jerdan must have received from Blackwood over a long association, he selected one from 1830 which mentioned L.E.L., evidently in response to Jerdan’s request for a notice of her latest work. As with other such requests, Blackwood chided him, “I have laid it down as a rule never to urge any of my friends to notice a book unless it is their own free will to do so, and that they can make an article which will be worthy of Maga…All the same, you must have observed how kindly she is mentioned whenever there is incidental occasion for it.” Jerdan concluded his column, observing that “the renown and profit of Scotland were far and wide extended by the impulse given to its press by William Blackwood.” Jerdan, the expatriate Scot, sounded wistful, possibly envying his Edinburgh colleague for his pre-eminent position in his native city.

The ‘Characteristic Letters’ in December, were from the writer and dear friend of Jerdan, the Irishman Samuel Lover. Like Bulwer, Jerdan wrote, Lover's work had been met by hostile criticism, marring his success and inhibiting him from reaping his just deserts. Jerdan quoted from a letter he had received from Lover, speaking of a “grief that smote my heart this morning, seeing the announcement of my dear friend Edward Forbes’s death. I cannot tell you how bitterly I feel his loss...we can't make old friends – and at our age new ones are not good for much – they don’t fit.” How Jerdan must have agreed whole-heartedly with this sentiment – he had outlived nearly all his old friends and many of his own family. Jerdan printed a letter dated January 1865, six months before Lover died, enclosing a “photo-proto-type of an owld sojer boy for Mop” (Lover wrote and composed a song, "The Bowld Sojer Boy," c. 1845) – he was god-father to Marion, Jerdan’s first daughter with Mary Maxwell. Although then 68 years old, he had joined the London Irish Volunteers, telling Jerdan his reason, that “Ireland was behaving so badly at that time, and about that grand movement, that I thought it incumbent on every Irishman in England with a spark of gentlemanly feeling and loyalty in him, to enrol himself among the volunteers.” Jerdan too set much store by “sparks of gentlemanly feeling and loyalty”, clearly finding a fellow spirit in his Irish friend.

Around this time Gaspey had evidently asked Jerdan’s advice about a piece he thought of submitting to the Leisure Hour. Jerdan told him that the magazine was running mostly Irish stories and suggested that Gaspey find another manuscript that might be better. He told his old friend that “my bairns take precious care of me now and all guard me against fatigue and risk of catching cold.” It was “tortuous or inconvenient” to get to Bushey Heath he knew, and anyway had no bed to offer, but there was one nearby. He hoped that both he and Gaspey would live until the Spring when perhaps he could tempt his friend to a visit (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives, Q/WIL/237). Jerdan’s mention of the care the children took of him is a rare glimpse into his home life.

At the same time as he was producing his ‘Characteristic Letters’ Jerdan renewed his interest in Notes & Queries. In January he wrote about popular superstitions, citing “a worthy laundress neighbour, in some distress” because a cock had crowed on two or three nights at nine o’clock, “a sure sign of an early death in her family.” It was indeed the hour she lost her last daughter. He also told how a robin “weeping” foretold death, and asked whether these superstitions were generally known. Another contribution was his version of a satirical song on the Four Ages of Mankind he once sang at a party, and in the same issue a brief note on the “salacious nature of shell-fish food”. February saw him energetically defending the record of the Royal Society of Literature against attack on its failure, followed by another two snippets of folk lore. His two contributions in May concerned the meaning of the word “Latten” and the border dialect word “skelp”. In August he referred to Walter Scott’s saying that “Old times are changed, old manners gone”, and recorded detailed accounts of some games played in his boyhood on Tweedside, already unknown to the present generation of children. There is something quite touching about an old man, nearing death, taking the trouble to ensure that his childhood games were described so minutely for posterity, and his observation that the times had changed so much that now the idea of boys and girls playing together was unacceptable. Later he remembered more games, and offered them to N & Q’s readers in December. He particularly recalled how swimming and splashing in the Tweed was enjoyed by the majority of boys, and that “It was a common custom to take to the river a bit of bread, which was called the ‘shuddering’ or the ‘shivering bite’ and eaten immediately on coming out of the water, to reanimate the exhausted frame. Is this a fashion elsewhere to restore the system? Is it done in the cold-water cure?” he asked. Another time he asked readers if they knew the word “nying” used in a book of 1580, and whether anyone could tell him about “Old Taylor the artist”.

Jerdan’s sense of humour, mostly of the practical joke kind, was legendary. In the New Sporting Magazine of November 1868 a writer, F Greville, related an anecdote about him in an article “Down and Up Again”, a collection of tales and myths about recipes and cures found in the natural world, that he was imparting to a companion: “I recollect once meeting Mr William Jerdan, of the Literary Gazette, who assured me, without a muscle of his face displaying a smile, that he was on his way to the London Tavern to see the exhibition of a new power whereby a man got into a common market-basket, and taking the two handles with his hands lifted himself off the ground.” A pointless kind of joke, but one can imagine it giving Jerdan a chuckle.

He tried hard to keep his spirits up; in a letter written to Bennoch in October,

I wither very slowly; but take matters in quiet; and can even (when I have breath enough in play) utter a jest. Being verbally pitied is a trial and the other day a caller consoling me with the assurance that I had in good time realized the fall into the sere and yellow leaf I comforted the Job-ber by acknowledging (sic) the fact that I must expect very speedily to hop the twig ... my cup runs low! [qtd. Pyle 245]

The end of the year was more cheerful when his daughter Marion, “Mop”, married Frederic Martin, the first of three marriages between Jerdan and Martin siblings. Marion was about 32 and Frederic also “of full age”, possibly younger than his bride. He gave his occupation as ‘Sailor’, and his father Charles’s as ‘Civil Engineer’. Charles Bickley, husband of Marion’s late sister Tilly and his new wife Julia, were witnesses to the marriage which took place not in Bushey where the bride had been living with her father and his young children, but at the Parish Church in Islington, close to Frederic Martin’s home.

Jerdan’s late burst of energy showed no signs of diminishing in his 87th year. With a wry sense of humour he marked Valentine’s Day with an entry in Notes & Queries: “A long while ago I knew St Valentine and was indeed privy to some of his little affairs ...” His next note was about an architect, Arthur Ashpitel, wishing “something more had been said” in a previous issue, and another answering a query about an author and composer whom he had known briefly “five or six-and-thirty years ago, as an emaciated shadowy creature, passing slowly away. If I could compare him to anything, it was to the last cadence of music sinking into the air....” 'A Scrap of Border Ballad,' and an accurate reply to a query about the author of ‘The Hermit in London’ first featured in the Literary Gazette of 1818, appeared in March. Jerdan’s last contribution to Notes & Queries was, fittingly, about da Vinci’s painting of The Last Supper:

Ne sutor ultra crepidam [do not offer opinions on things outside your competence] is my ardent motto, yet I fancy I sometimes notice things in productions of art which have escaped great critics. Thus, negatively, veluti in speculum [as in a mirror], in carefully examining the immortal Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci, I discovered that, though there were twelve disciples, there were only eleven glasses. I would fain inquire if the artist meant a fling at Judas – a slight which might inflame his treachery? It is a curious question relating to so famous a work. [s.III, 27 March 1869, p. 287]

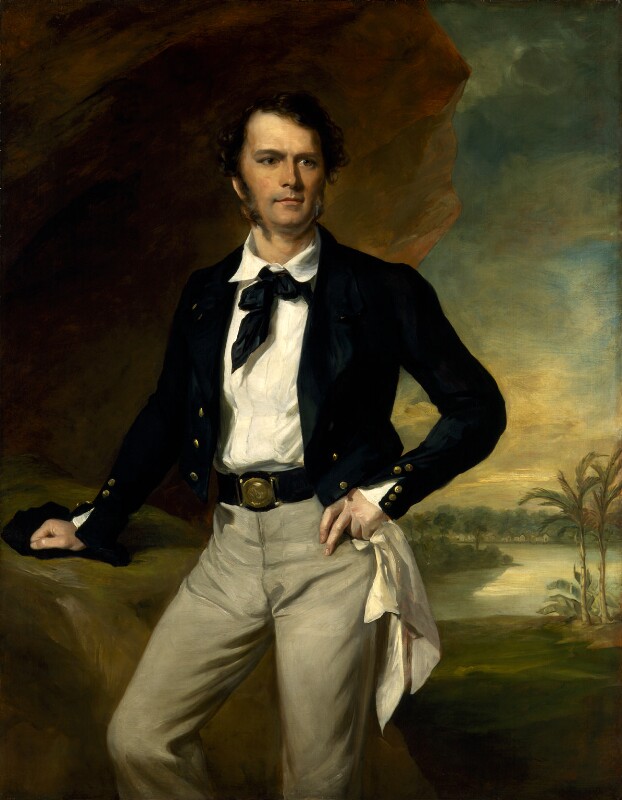

Sir James Brooke by Sir Francis Grant, 1847. courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery.

‘Characteristic Letters’ were still in full flow. The new year 1869 opened with “Rajah Brooke”, the late Sir James Brooke famous as the Rajah of Sarawak, and included two drawings by his subject. John Claudius Loudon was February’s man; he had written monthly for the Literary Gazette on gardening and horticultural topics. Horrifyingly, Jerdan reported how ill Loudon had become and called in Dr. Thomson (who had also attended L.E.L.) Thomson told Jerdan that he had “repaired” Loudon. “He had treated him, he said, just as he would have treated an old decaying tree in his arboretum – lopped off a huge withered branch here, cut away several diseased members there, scraped off gangrenes and stopped injurious holes and cracks, all which the patient had borne with a firmness worthy of the aged tree itself!” In 1825 Thomson had amputated one arm at the shoulder and some fingers of Loudon’s left hand – upsetting reading for the Leisure Hour. A note on Ackermann completed this issue, although Jerdan forbore to quote his friend’s letters as, “like his German pronounciation of the English tongue, so droll, that they might convey quite an erroneous impression of his solid common sense and enterprising attention to business.” In August Notes & Queries published some corrections to this section, but by then it was too late for Jerdan to care.

As Jerdan had noted of Loudon, that he had barely survived by his writing, so did he stress this point again in March when he spoke of Patrick Tytler, an “eminent historian”. Jerdan had enlisted him to write a History of Scotland for the ill-fated ‘Juvenile Library’, and took this opportunity to list many of the other eminent writers he had similarly commissioned. He “could never divine”, he said, “why the series had been “broke off i’ the middle” but was plainly still upset about it, thirty-five years later.

He then made an opportunity to tell of his part in the romance of George Croly, when he was instrumental in introducing him to his future wife through her poetry. His role as Cupid culminated in him giving the bride away, “as a friend of her deceased father”. Jerdan generously believed that Croly’s writings were as worthy of posterity as Charles Lamb’s Essays of Elia, but regretted that they had not remained as popular. The letters he printed included two in which Croly had scolded him roundly, one concerning a bad review in the Literary Gazette which Croly had not read himself but merely heard about; in the other, which Jerdan called “curious”, Croly stated, “I wish, of course, to be always on the thickest terms with you, but yesterday you used careless language…you said also that I was ‘holding a candle to these persons’. This was an ill-considered expression. Do you mean to say that whoever writes for a periodical work necessarily holds a candle to its editor, or that I, in contributing to the Literary Gazette hold a candle and act the menial to you?” Jerdan thought this letter was “replete with character”, and his publishing it alongside more poetic letters of Croly, demonstrated that his eagerness to present all sides of his subjects overrode any vanity on his own part, where his behaviour was called into question.

The section on Sir James Ross in May throws another light on the way Jerdan’s expertise was asked for and freely given, with or without the label of ‘literary agent’. Ross knew that Jerdan had negotiated the sale of his colleague Fisher’s book to Longmans, and in 1843 was deciding on placing his own account of the expedition to the South Pole.

I have an offer from Mr Murray of the same kind as that of Longmans & Co., - namely sharing the profits. I am so little conversant in these matters that I am not aware whether their offers or that of Mr Bentley are the most advantageous, and am desirous of availing myself of your very kindly offered assistance in coming to a decision in the matter. I have always heard of the difficulty of knowing the amount of profit, and been rather led to prefer money down.

Ross finally chose John Murray’s higher bid. One of Ross’s letter referred to “Jerdan Island”, giving its dedicatee the chance to tell his readers how Captain Waddell (sic) had named a large island off Cape Horn after him, and that it was “illustrated by a chart (now in the British Museum Library).” Jerdan hero-worshipped Ross, concluding his column by noting, “It related to one whom, from his extraordinary labours in both hemispheres (planting his foot upon the Arctic and penetrating within 160 miles of the Antarctic Pole), I esteemed ‘the noblest Roman’ of all that illustrious band of explorers with whom I held intimate acquaintance, from Captain Parry to nearly the latest.”

Jerdan’s June contribution to ‘Characteristic Letters’ was more interesting for the idea behind it than for the individuals portrayed. He grouped together the editors of daily newspapers, men of vast influence: “The great voice of the nation, or what is commonly called ‘public opinion’ is the real power in a free country like England…An editor is sagacious and skilful as he has judgment to know and tact to follow and to express the national will. Doing this well, editors of daily journals are among the real rulers of the people.” Who are these unknown men, he asked. “They are men of rare and superior talent and ability, placed by circumstances in a position which affords them immense authority over not merely the multitude, but all classes of society.” Such praise of editors cannot but raise the question as to whether Jerdan had seen his own long role in the Literary Gazette in the same light, as knowing how to “follow and to express the national will”, although in his case it would be “the national taste”. Was his early success at the Literary Gazette because he followed public taste rather than formed it, or perhaps it was a balance of the two. He chose Burns of The Times as the first editor to feature, recalling how he had annihilated Jerdan’s hopes of becoming an MP with his “trenchant” leader, “denouncing the pretensions of literary men to become legislators”. Jerdan charged Burns with treachery, but they soon restored good relations. Jerdan’s other editors were John Black of the Morning Chronicle and William Mudford of the Courier; he wound up by noting that it was not only their “leaders” that created their influence but that “It is the promptitude, the judgment, the decision, which is demanded from them at every hour of their difficult lives, which constitute their real value and right to the power they possess. Each must not only be the central moving wheel, but he must direct the lesser motions; he must take care that none of the smaller wheels get out of order, he must regulate the entire action so that all tends to the end in view, and that there is perfect unison and consistency in every part of the wonderful and complex machine.”

Appearing in July were letters from the popular historical novelist G.P.R. James, whom Jerdan had known since his youth. The Literary Gazette had favourably reviewed James’s first work, The Ruined City, thirty-two pages published privately in 1828. He printed James’s letter of thanks and astonishment that such a small work was noticed at all; Jerdan felt it necessary to add a footnote exonerating himself from any blame of egotism, as “To him, as to many aspirants during the third of a century, it so happened, from my position as editor of the Literary Gazette that I was of some service. There were many authors, artists, antiquaries, inventors and others, thus introduced to the public. Lending a hand up the first steps of the ladder is no great service, but the grateful remembrance of it is even now warmly expressed by the few survivors of that now distant and all but forgotten day.” This really summed up Jerdan’s thoughts on the whole matter of being an editor, to help people on their way, and to be thanked for his help was all he desired – although gifts were always welcome too. It was ingratitude he could not tolerate, a theme which had found its way into his Autobiography on several occasions.

Thinking back over his life, or perhaps on looking over his papers for ‘Characteristic Letters’, something must have jogged Jerdan’s mind about Fox Talbot, one of the inventors of photography with whom he had corresponded on and off for thirty years, Fox Talbot’s descriptive letters featured often in the pages of the Literary Gazette as well as the journal’s biting response to the Quarterly’s criticism of his English Etymologies. Even after Jerdan relinquished the Literary Gazette the paper printed an account, in November 1852, from Fox Talbot of “The Traveller’s Camera”. Jerdan’s sad note to him dated 8 March 1869 read:

It is so long since our agreeable correspondence ceased, and I remember from fighting the great Photographic battle by your side, that I am afraid to address this letter – as if we pilot a balloon to discover what wind blows.

I am so deep in the sere and yellow leaf of age and jaundice that you could hardly believe I was still of this world. But I am, and if you are and hold the memory of former days, it will afford me a very great gratification to hear from you. [Correspondence of William Fox Talbot, Doc. 9504]

In March 1869, four months before he died, Jerdan’s article entitled “The Grand Force” was published in Fraser’s Magazine. For an old ailing man it is a surprisingly vigorous attack on the power of advertising. He had reason to be suspicious of advertising in all its forms: he could not have avoided recalling the controversy over his so-called “puffing” of Colburn’s books in the Literary Gazette some thirty years earlier and the problems that accusation caused him. In this contribution to Fraser's, he used the device of challenging a Professor at the Royal Institution lecturing on Mechanical Forces, on the grounds that he did not include the greatest force of all. He maintained it was a Force that can stir the world, “compelling mere words to alter, confuse, and confound the realities of things.”

In support of this large claim, Jerdan’s article gave examples of the power that advertising wielded, none in praise, but rather showing clearly the economic consequences of this fast-expanding phenomenon. “The Advertisement can import millions of chests of tea direct from China, and sell cheaper than sloe leaves and carpet sweepings!” “The Advertisement can cleanse the Augean stable of millions of boxes of bottles of quack medicine, and induce millions of fools to anoint their bodies with, or swallow their contents!” Advertisements for adulterated wine and beer were included in his tirade, as was promotion of the railways; these, he raged, created huge profits but admitted they had never been known to “kill even One of the well-assured multitude who trust their lives to consequences so satisfactorily accredited.” (This was not true. The first person to die was in September 1830 — see Chapter 5, n.12. Further deaths had occurred on railways since then.) Jerdan became particularly exercised in referring to advertisements supporting foreign loans (i.e. Greek); promoting ‘bubble’ companies, and lending money to individuals without security which, as he knew to his cost, can “gull hundreds of thousands of idiots into disastrous loss or utter ruin.” The press incurred his wrath too. Advertising supported countless good, bad and indifferent periodicals which in turn promulgate “sensationalism, spiritualism, ritualism, political associations, monster meetings, nonsense, trash, rubbish, imposture, and poison of every possible kind....” His frustration boiled over, and he finally got to what was at the core of his complaint. Times had moved on and left him behind. The extent of advertising is “one of the most extraordinary proofs of the mighty change which has taken place in the manners, morals and doings of the civilised world.” Jerdan focussed on the injustice he perceived: low rogues and thieves were transported, whilst nothing is done against rogues and thieves who are wealthy mercantilists.

Advertising, Jerdan was trying to prove, was responsible for most of society’s ills. The dishonest used it to tempt the public, leaving “the honest, in self-defence...to have recourse to the Greatest of all Forces.” His hopeless solution to these iniquities was Silence. A postscript to his article noted that since writing it “about four-fifths of a new Parliament has been elected by means of the grand force; which has thus demonstrated its power to shape the course and determine the destiny of the British Empire.” The image of Canute trying to keep back the waves, or the boy with a finger in the dyke, is the image of Jerdan, hating the new world around him, unable to participate in it and railing angrily against progress.

Following Jerdan’s diatribe about advertising in Fraser’s issue of March 1869, in April he contributed a companion piece, “The Greatest Wonder”. This time his target was the law. Despite all the advantages of being British, “the Greatest Wonder of the age appears to be the entire absence of common sense and simplicity in the legislation of our prosperous and gifted land!” The progress of civilisation, he wrote, has become so complicated and the world so crowded, that the rule was now “Every man for himself”, unlike olden days where wise men guided the people and only two religions, Deism and Pantheism reigned. Now, he complained, there are numberless creeds and sects, leading to endless quarrels. This is analogous with the law: previously there were rules and subjects (generally tyrants and slaves), with no “Peoples” of middle class to disturb the system. Jerdan went on to say that the same change and enlargement permeated all aspects of modern life. There had been a great mistake in the belief that for every ill, social or medical, there was a cure. This was not necessarily the case, but in the endless search for remedies, absurdities and worse occur.

Taking the law as his quarry and example, Jerdan posited what happens when a Lord Chief Justice cannot rule on a case; he calls in three other judges, and if agreement cannot be found the case goes to the House of Lords. Here the whole House rules on a case about which they know nothing and are therefore, quipped Jerdan, “impartial”. Furthermore, law has little to do with justice – a judge may deem a litigant’s claim just, but must follow a precedent which could indict him. This discrepancy frustrated Jerdan who asked irritably “… has it not occurred to our legislators to render law intelligible”. Laws had been promulgated in vast numbers, in an attempt to “stop every hole, strengthen every flaw, fill up every crack…” resulting in monster legislation with deleterious effects. He thought it was a gamble, a lottery.

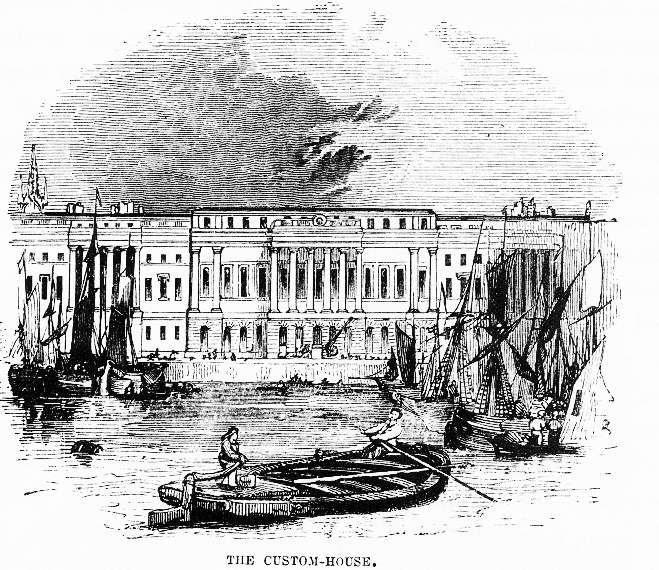

The Custom House, designed by Robert Smirke, i825-7. Lower Thames Street, London EC3.

Acknowledging that serious debates upon law reform had taken place, Jerdan nevertheless wanted to throw his “little arrow” to penetrate “where a spear could not be thrust”, by proposing some ideas towards reform and improvement of common and criminal law, and their administration. Taking common law first he focussed on shop-keeping, where there were laws laying down punishments for cheating and fraud, but in practice these powers are seldom exercised. Jerdan asserted that this had resulted in a lax moral system where goods are habitually adulterated and nothing is what it should be. This, coupled with fraudulent weights and measures, had the worst effect upon the poor, where “we are utterly shocked by the universal prevalence of gross impositions, injurious alike to economy and health.” In former times rules relating to weights and measures were enforced by a Court Leet, efficient once but now barely functioning. The Custom House and Excise office possessed powers, but loosely employed. Could there not, he suggested, be a National Minister of Justice over an unimpeachable Court Leet, to redress the evils of adulteration and fraudulent weights. In addition to the obvious moral improvement to society, Jerdan insisted this would relieve the country financially too. The cost of penal settlements, penitentiaries and poor rates would dramatically reduce and the whole community would be happier. As if realising that this may be too heavy for Fraser’s readers, he commented that his remedy may seem a jest, and that he tried to make the subject light, but that even so he thought that some good may arise from his idea.

His treatment of criminal law was even more robust than his discussion of common law. Its “farces, pantomimes, spectacles and tragedies… its effeteness and hazard-game are enough to condemn it to all rational minds…” Jerdan expostulated about the financial cost involved in legal actions against all criminals who, when imprisoned, have to be kept at the expense of the public purse or, as he more picturesquely remarked, “The tax-payers pay dear for their wild beasts”. He calculated the cost to be between £700 to £1000 per criminal. His solution, a “little game” which may go some way to reforming convicts and opening a door for them to rise in the world. He presented this idea for the consideration of the Foreign Minister, Lord Clarendon.

As the threat of transportation to the colonies had not significantly decreased the crime rate, Jerdan suggested entering into alliances with various African rulers, whereby England would provide say twenty convicts a year at no cost, the number varying according to the size of the nation. The rulers could then use the convicts as they wished, taking advantage of such talents as they had. The prisoners would thus have the opportunity to “mount in the African scale”. Jerdan recognised that this might seem an attractive option for some leading to an increase in crime, so “cargoes of Thames pirates” could be sent to Timbuctoo or the Ashantee kingdoms, to take their chances under despots who enjoy “butchering thousands at a single festival”. This plan would dispose of all undesirables from our shores and if successful, Jerdan satirically hoped for a Statue of Gold in his honour, for restoring a golden age to the British Empire.

This was Jerdan’s final article published in his lifetime, appearing in April, the month he celebrated his eighty-eighth birthday, and was a neat conclusion to an exceptionally long life and literary career. The Theatrical Journal of June 1869 noticed this article, commenting that “Mr Jerdan is still vigorous, his intellects are unimpaired by time, and he is now engaged upon the MSS of his old friend Samuel Lover, whose unpublished works he is preparing for the press.” Jerdan did not manage to complete this task, but in 1874 a “Life of Samuel Lover ... with selections from his unpublished papers and correspondence” was written by William Bayle Bernard. In 1880 A. J. Symington included a sketch of Lover, with a selection from his writings and correspondence in his book, Men of Light and Leading, London, 1880. They may well have used some of Jerdan’s papers for these books.

In May, Jerdan received a note from Charles Dickens: “I grieve to find you describing yourself as ‘sorely crippled’, but I hope and trust that the departure of these horrible winds and the coming in of balmy weather will let in a shower of genial influences upon you. In the meantime I can declare this: that I never saw a handwriting as unchanged as yours, My dear fellow, the out of the way village made a triumphant appearance immediately” (Letters of Charles Dickens, 14 May 1869). This note was endorsed by Jerdan “A botch! The whole sequel story's left out”, an unexplained reference. Dickens’s reference to an “out of the way village” may be to Jerdan’s signature on his many offerings in Notes & Queries, where he signed himself ‘Bushey Heath’.

Bibliography

Pyle, G. P. “The Literary Gazette under William Jerdan.” PhD dissertation. Duke University, 1976.

Created 20 June 2020