1835 opened with the worst possible news for Jerdan. His first-born son John Stuart, on whose behalf he had importuned the Duke of Portland for a job, had died aged twenty-six. In response to Jerdan’s persistent requests that a post be found for him, he had been sent as a stipendiary magistrate to Jamaica. His death occurred on Christmas Day 1834, and his obituary in the Jamaica Dispatch was copied in the Gentleman’s Magazine of March 1835. “To an active and enterprising character he added a zeal in the execution of his arduous duties, which rendered him respected and beloved both by master and servant; he tempered justice with mercy” (325). John Stuart’s previous work as Secretary of the Abbotsford Subscription was also mentioned, “seconding the ardent wish of his father for its success.” It was also noted that he was attached to the study of natural history and had made his fine collections in entomology in England, the Netherlands and Jamaica. Jerdan probably had a hand in the obituary in the Gentleman’s Magazine, which ended proudly, “He was nephew to Colonel John Stuart Jerdan, whose remains lie at the Cape of Good Hope.” The just deceased John Stuart had married the elder daughter of distinguished engraver, John Vendramini; it is not known if they had any issue.

The eldest child at home was Frances-Agnes, now almost twenty-six, with Mary aged twenty-one, soon to be married, William Freeling, nineteen, running errands for his father and generally assisting with the Literary Gazette, George Canning, only seventeen, not yet out in the world and finally the baby of the family since Georgiana’s death, Elizabeth aged fifteen. All these, plus his wife Frances, were a heavy responsibility for Jerdan, presumably in addition to the upkeep of the three children he had with Landon who were still aged only thirteen, nine and six. Grove House had gone, and with it the fine lifestyle of parties and dinners, and the visible, tangible evidence that he was a man of some status in society. With all these burdens and anxieties the marriage with Frances was under strain, if not entirely broken down. Jerdan would have heard of the scandalous rumours about Letitia Landon, and maybe harboured some doubts as to their foundation as far as the other men gossiped about were concerned. Despite all this, during the next couple of years he was to complicate and burden his life still further.

More than a hint of Jerdan’s despondent mood could be found in a poem he wrote in February 1835, published in Friendship’s Offering for 1836, and entitled On My Grey Hairs. Recalling how at the beginning, each grey hair was plucked as it appeared, his second verse said:

Those years are fled, I greet you now

The dearest guests to me;—

Why should the stem live when the bough

Falls withered from the tree?

When keen afflictions piercing blast

Hath nipt the foliage free;

And when the storm hath torn the hopes

Of blossomings to be!

The poem concluded,

But loves, and fears, and griefs, and tears,

All centre in the grave.

With the death of his son, and troubles with Landon, Jerdan’s life was clearly unhappy, and this poem comes across as more true than his earlier melancholic L.E.L.-type offerings in other annuals.

In early 1835 Jerdan’s downturn in fortunes was making him short-tempered. He had disagreements with Bentley over some of the novels that came from the publisher, and was not afraid to state his opinion:

I am sorry to notice that I do not think you can be led by their merits to some of your Novels; and it is bad policy to be induced to publish indifferent ones, with only a star now and then. Nothing short of superior class will do now; and the mediocre must serve to pull down the high.

I wish you were better advised, but you publishers are almost all alike obstinate fellows! It may be however in this case as in others that lookers on do no more than fancy they know the game better than the player. [30 March 1835]

Wishing to be free for Ascot Week, Jerdan asked Bentley for any novels he wished to be noticed to be sent quickly. He could not resist giving the publisher some advice in a letter of June 2nd: “Only beware of poor and bad works as much as you can and rely upon it you may place yourself at the head of the publishing trade. Also be very direct with all those you have to treat with about MSS etc. etc. Pardon my advising” In Jerdan’s opinion Bentley did not always follow this well-meant advice. Notwithstanding Jerdan’s warnings, Bentley’s publishing house continued with some success, and Bentley himself was to become the recipient of many of Jerdan’s anguished letters pleading for financial help.

Despite the trend away from poetry to prose, 1835 saw the publication of another volume of Landon’s poems, The Vow of the Peacock and Other Poems, published by Saunders and Otley. Many of the poems had been previously printed in the Literary Gazette, and the theme of the title poem came from a painting by Daniel Maclise. The Literary Gazette of 24 October reviewed the new book, vilifying complaints that pseudo-Utilitarians made against the ‘school’ of L.E.L. The reviewer, if it was not Jerdan, could well have been Landon herself:

Pseudo-Utilitarians tell us that the love of poetry is over; and that, under their auspices, the human kind have become a mere shrewd, calculating, sordid, work-o’-day race. That to toil, and to spin, to draw water, and cleave wood, to gather and amass, to drudge and hoard, and never to enjoy, is the wisdom, the only wisdom of life. We are ready to believe their doctrines when we shall be convinced that the love of gracefulness and beauty, the fine moral perception, the sense which gives a tear to sorrow, the noble enthusiasm awakened by illustrious deeds – when natural feeling, sympathy, generosity, and heroic aspiring, have all departed from among the children of men. And not till then.

The passionate refutation of this so-called pseudo-Utilitarianism continued, the very passion suggesting that the writer was Landon herself, defending her poetry. In a letter of 29 December 1835 Jerdan, as usual, urged Blackwood to review the book: “I do not remember if you have noticed Miss Landon’s last Novel (sic) The Vow of the Peacock. I am sure you have not; shall I transmit a copy or copies” (National Library of Scotland, 4040/302-3). (William Blackwood died in 1834. The Maga was run by his sons Alexander and Robert, until John Blackwood took over in 1845.)

Maclise had made a portrait of Landon for the frontispiece of The Vow of the Peacock. He had also made one for Fraser’s ‘Gallery’, but it is likely the former which became the subject of his undated note to Jerdan that the price for such a drawing was ten guineas (Edinburgh La.II 648/149). Landon told Jerdan that she was “much surprised about the portrait but Mr Maclise may I am sure keep it since he takes it back again” (Landon papers, John Alexander Symington Collection, Rutgers University Libraries). Jerdan sent this note on to Crofton Croker, complaining that he had sent the portrait to Saunders and Otley (publishers of The Vow of the Peacock), “and though our friend M’Clise (sic) misliked the Engraving it does seem too bad that he shd like my picture and keep it. Miss L. of course will not ask him for it again and I am between the stools unless I make a row with Saunders and Otley. Pray take an opportunity of mentioning this matter in a friendly way to M’Clise, from who I do not think that I deserve any wrong (Landon papers, Rutgers).

In September 1835 Jerdan’s story “The Line of Beauty: or, Les Noces de Nose” appeared in the New Monthly Magazine. It was the story of Ned Redmund, “almost a universal genius; that is, he knew a little of everything and in our days very little serves”. Of independent means, Redmund was a connoisseur in the fine arts, but anything outside of the Line of Beauty was “error and abomination”. He followed a woman, bewitched by her figure, and then he examined her face. Jerdan’s sense of humour is apparent as he described her nose which: “took its rise between a pair of eyebrows...not wholly joined; nor yet just quite apart”, and descended in a straight line towards the upper lips; “neither too short nor too long, neither cocked up impertinently, nor drooping disagreeably; neither pinched in avariciously, nor dilating passionately…it was the juste milieu of noses!”

Plans were made for marriage, but disaster struck, as they rode their horses towards Regent’s Park. Jerdan could not resist a bit of harmless fun when he chose his location. “Just opposite Lockhart’s house a dirty-looking boy ran hastily past, and the creature started, fell and threw its rider; which was not surprising, as it happened to be a printer’s devil carrying the copy of an article on Melton Mowbray for the Quarterly Review.” On rushing to help Betsy, Ned’s horse came too near to her prostrate form and his iron shoe struck her face, mutilating it horribly. “after weeks of darkness and bandaging and suffering, it was found that her nose, that temple of beauty worshipped by the disconsolate Redmund, was irrecoverably gone”, and it was all Ned’s fault that the Line of Beauty had been annihilated.

Having set the stage of the tragedy, Jerdan brought into his story the celebrated Scottish surgeon Robert Liston, who had reconstructed noses in Edinburgh, and to whom he had dedicated his tale. He was now in London, and Ned consulted him. Hope instantly improved Ned’s health and outlook, giving Jerdan the opportunity to satirise the florid language so beloved of L.E.L. and other contemporary novelists:

Hope, that takes its seat on our nature’s throne, and issues its decrees to all the vassal vessels round, till brightness gleams from the dull eye, smiles dimple on the languid cheek, breath flows freely from the choken throat, the red blood circulates briskly in the stagnate veins, the heart beats lightly, the foot treads firmly, and every look and motion bespeak the balmy influence of the rosy and god-like monarch who reigns when ‘Hope told a flattering tale’.

Though frightened, Betsy agreed to an operation because, as Jerdan remarked, “nobody likes to be without a nose and few girls to be without a husband”. Ned had told Liston that “a mere nose” would be an acquisition but for him to be happy, it needed to be Greco-Roman and consistent with the line of beauty. When Betsy healed, the result was almost perfect except for a slight dip at the tip. Another operation was performed, and the happy couple were duly married.

Jerdan’s postcript to his story was an acknowledgement that he had witnessed a similar operation in London’s University Hospital a few months earlier, and hoped that Mr Liston would not take offence at the freedom taken with his name and skill in the story. Pleased with the reception given to the tale by the Courier and elsewhere, Jerdan approached Blackwood mentioning it, as it had “inspired a desire to write a few papers in some Maga for the ensuing year.” On 29 December 1835 he sent a sample, promising that his contributions would be better, and leaving the ‘reward’ to Blackwood, “as I have promised proceeds to a destined purpose, and not of a selfish kind.” (National Library of Scotland, 4040/302-3). However, no contributions of Jerdan’s appear to ever have been published in Blackwood’s.

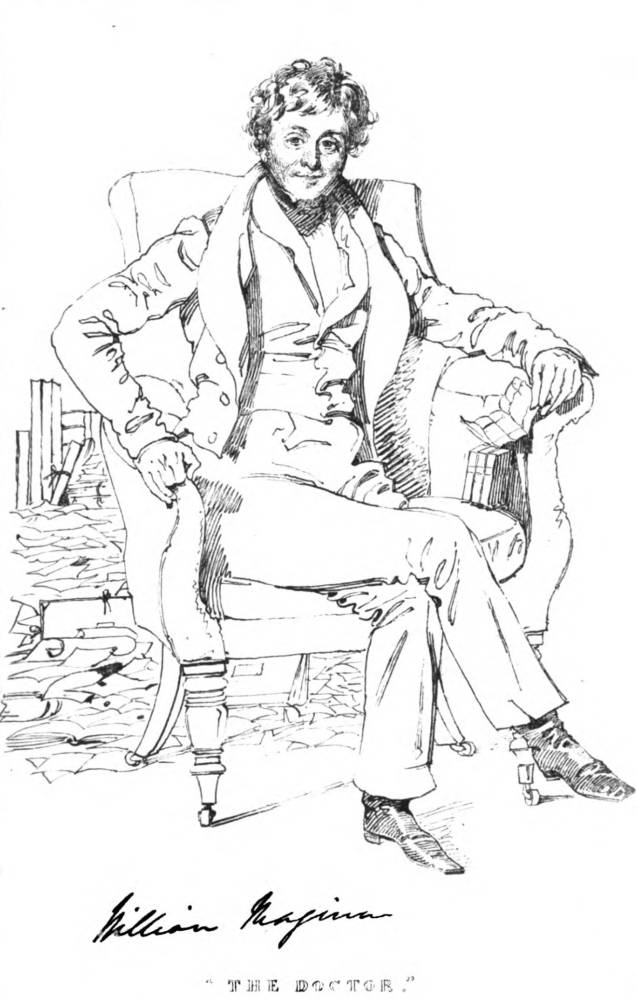

William Maginn by Daniel; Maclise.

Jerdan continued his life as normally as possibly, retaining his great love of the theatre, and his friendship with the actor Macready, who recorded in his diary that Jerdan came to his room three times in four days in August. They discussed the breakdown of Lord Byron’s marriage, and Jerdan agreed to accompany Macready to Wicklow. They met up again in September when they saw a five act comedy at the Haymarket, and thought it dull and commonplace. On 20 November Macready went to call on John Forster “and stayed some time listening to a tale of wretched abandonment to passion that surprised and depressed me”. This was the breaking off of Forster’s engagement to Landon, having apparently heard that she had twice “made an abrupt and passionate declaration of love to Maclise.” Macready also heard the story of the Maginn letters. He had never met Maginn, but had heard he was “a beastly biped”. The fastidious Macready was revolted by the whole affair: “I felt quite concerned that a women of such splendid genius and such agreeable manners should be so depraved in taste and so lost to a sense of what was due to her high reputation. She is fallen.” Fortunately for Macready’s sensibilities, he had no idea of the truth about L.E.L. He was not the only one to have heard about Landon and Maginn. in Glances Back H. Vizetelly recalled that Grantley Berkeley (who had famously duelled with Maginn), reported that “before his duel with Maginn, Miss Landon (L.E.L.) had appealed to him for protection against the doctor’s persistent persecution, asserting that, although a married man, he had made much too ardent love to her, and not meeting with the encouragement he expected, had then endeavoured to extort money from her” (1.126). One wonders why, if Landon was truly troubled by Maginn, she did not go to Jerdan for some “protection”, rather than to a man with whom she had little to do.

Jerdan’s bank account for 1835 opened with a debit of £4178, reflecting his dire situation as a consequence of his imprudent investment and the loss of Grove House. No details of transactions have survived after January until July, when his debit had deen reduced to £72.10 probably by the sale of house contents. This substantial improvement goes far to corroborate Jerdan’s claim that he eventually paid off his debt. Transactions on his account between July and December 1835 reveal eleven withdrawals for himself, mostly around five to six pounds, with an unusual thirty-five pounds in August, perhaps for holiday expenses. Payments to “Mr Jerdan” are likely to refer to William Freeling, possibly for his assistance on the Literary Gazette. In August, October and December these were for five pounds and in November for five guineas. There are disbursements too to “Mrs Jerdan”, and others to “Home” or “House” at five pounds a time, at irregular intervals. Names recurring are those of Biffin, Chambers and Grant, but to what these payments refer is not known, although they are quite possibly instalments to clear loans. The total of Jerdan’s debits in this six-month period amounted to about £480. On the credit side, this exactly balanced his income, which comprised deposits of sums varying between £5 and £100. Where the payments came from is not listed, but Jerdan was drawing his regular salary from Longmans as Literary Gazette editor, and being paid for contributions to other journals, such as the New Monthly Magazine for his story of “The Line of Beauty”. The sum of one hundred pounds paid in December may have been his partnership share in the Literary Gazette, but the precise reasons for his payments and receipts can only be the subject of speculation.

In November 1835 James Hogg died and was buried in Ettrick. The sad event would have brought mixed memories to Jerdan’s mind: the famous Burns Dinner, Hogg’s desire to bind their two families by marriage, and the dire poverty that had necessitated Literary Fund donations, even for so successful an author. Writing to his brother on 27 November 1835, Thomas Carlyle recalled the last time he had seen Hogg, and went on to remark how glad he was that John Carlyle had met with William Fraser. He had himself been enquiring about Fraser, but without result. “the monster Jerdan of the Gazette had not ‘heard a word of him’ two months ago and was and remained a satyr-cannibal Literary Gazette-er; who shall live (leben hoch [live high] if he like and can), only far from me.” (Carlyle Letters)Carlyle disliked Jerdan for his huge energies and love of life, drink and women, contrasting strongly with his own strait-laced personality.

Dilke shared Carlyle’s dislike of Jerdan, the latter for his personal traits and the former for his perceived ‘puffing’ in the Literary Gazette and subservience to Colburn. Dilke received a very long letter from Thomas Hood, written from Coblenz in January 1836, and referring to some news Dilke had recently sent to him:

By the bye the Jerdan story – his application to you for character etc. is astounding! The net is plain, a plan to entrap same [some] easy rich man into marriage with his daughter – but the application to you reads to me like a drunken audacious Garrick Club or Beefsteak Joke!!! Are you sure it is not one of your own on an innocent at Coblenz? After that, come any thing. Is the day fixed when Wentworth and Agnes Jerdan are to be united? I will come to that wedding anyhow. I must believe you – but after that I think I can play the Boa with a whole rabbit. [Marchand 49]

In a footnote the editor noted:

Wentworth was Dilke’s son, Charles Wentworth Dilke II, born in 1810. Is he the “easy rich man” whom Jerdan wished to entrap into marriage with his daughter? It seems hardly likely. The greater probability is that he merely wanted to make use of Dilke’s good name to further his interest with another, and that Hood’s suggestion of a union between Wentworth and Agnes Jerdan was only his jesting way of indicating how ridiculously absurd he considered Jerdan’s proposal, whatever it was.

Jerdan considered Hood his friend, a regard that does not seem, from the tone of Hood’s letter, to have been reciprocated.

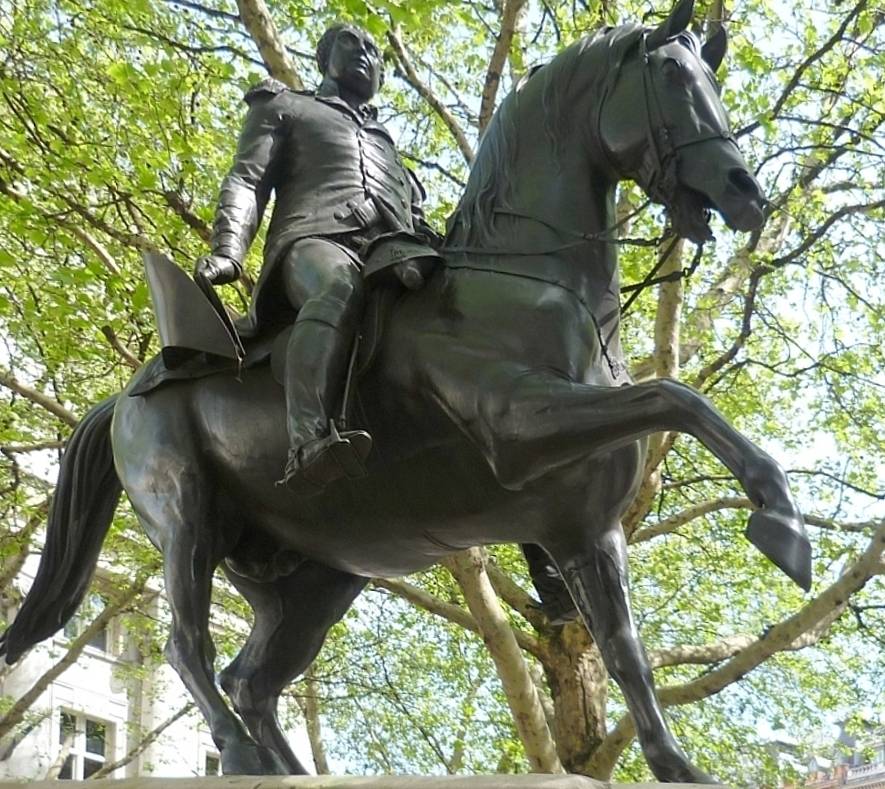

George III. Mathew Wyatt. 1836. Cockspur Street, London.

Since 1820 Jerdan had been trying to popularise the idea of a fitting monument in London in memory of George III. The wildly ambitious proposal by Matthew Wyatt of the king on a car drawn by four horses attended by angels had not been practicable as insufficient subscriptions had been raised to meet the cost. All these years later a much more modest monument came to fruition. Jerdan heralded it in the Literary Gazette of 27 February 1836 announcing that it would be erected on 4 June, the late King’s birthday. More money was needed, and to grip his readers’ attention the Literary Gazette article included a large engraving of the horse’s head, and referred to, but did not explain, an accident which had befallen the project but had been surmounted by Wyatt. Nearer to the great day, the Literary Gazette of 28 May 1836, said of the Committee, “Their labours and exertions, and the public can hardly surmise how great they have been, are now on the eve of a triumphant termination.” The statue was to be erected that week, in the presence of royalty and nobility. More in hope than expectation, Jerdan wrote “we think may promise the opening of an Equestrian Group which no age or artist has ever surpassed.” Subscriptions had amounted to £3130.4.1. (The figure given in 1822 was already £5000 but perhaps this reflected the changed value of the pound). It was hoped that additional subscriptions would be forthcoming, “to reward the talent and exertions of the artist in a more suitable manner.” Far from the elaborate and allegorical statue first designed, the nation’s memorial to King George III was a twelve foot high granite pedestal surmounted by a sculpture of the King, wearing a pigtail, seated on his horse – not quite the “Equestrian Group” of which Jerdan spoke. The pigtail was much derided at the time and even the site chosen caused objections, which were overridden by the Lord Chancellor. The statue is still there, in the triangle between Cockspur Street and Pall Mall East, now sadly isolated by streams of traffic, and ignored by throngs of tourists hurrying into Trafalgar Square.

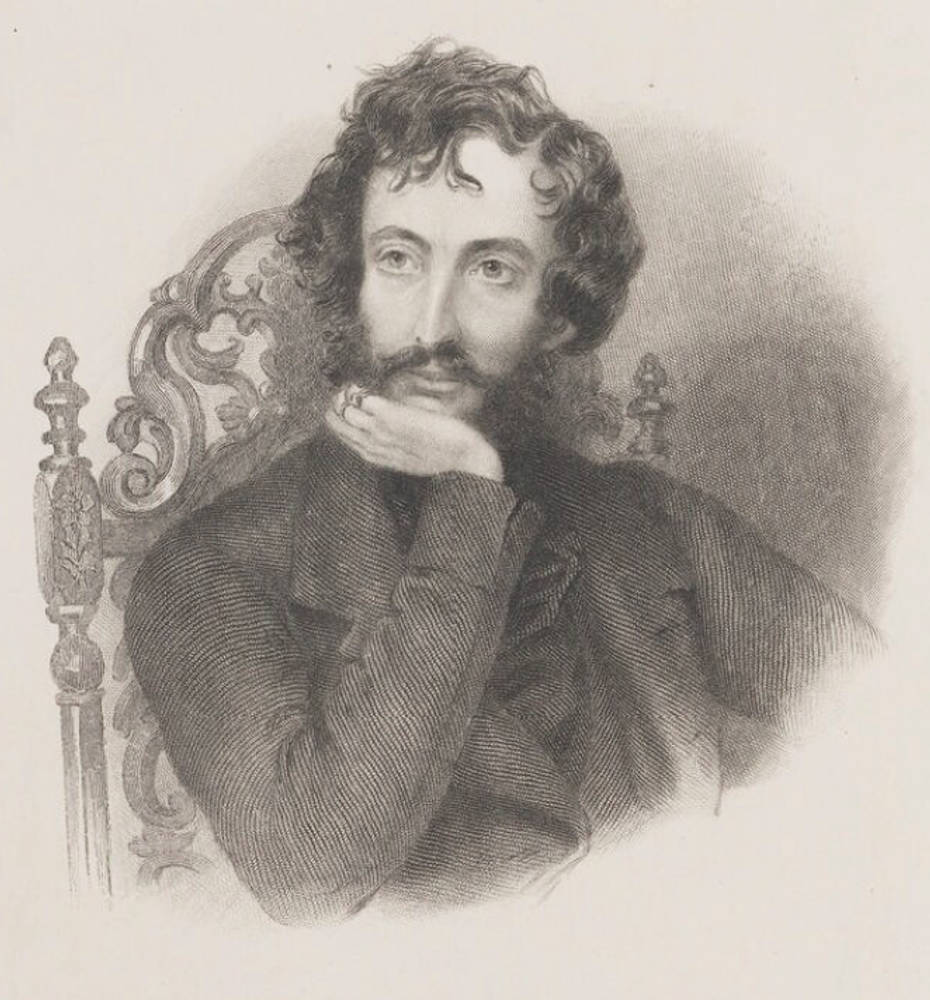

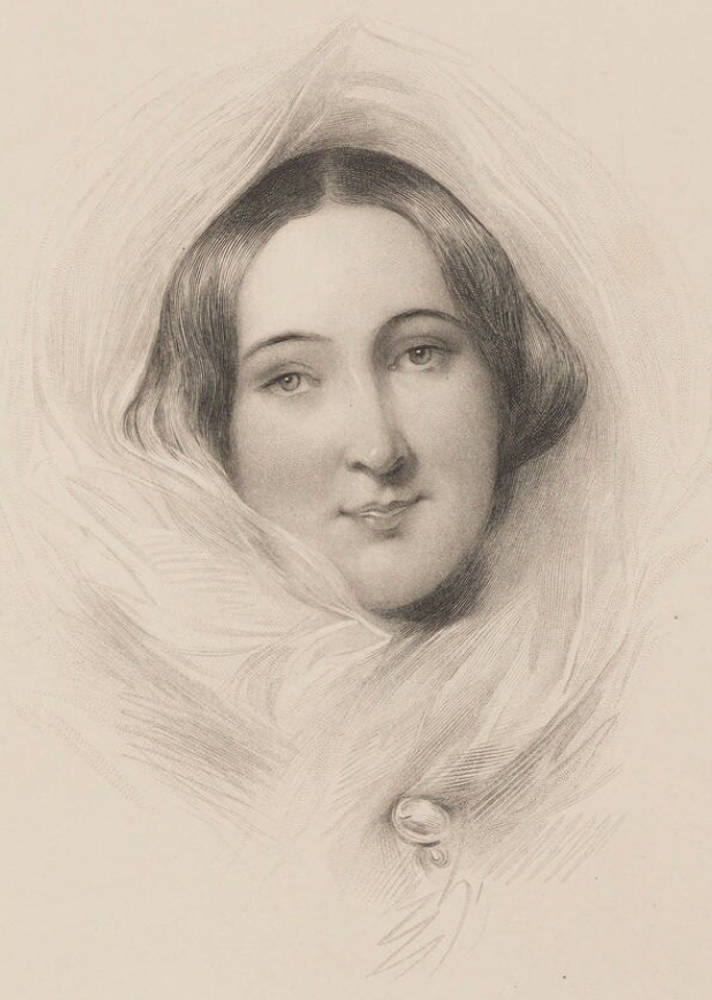

Left: Edward George Earle Lytton Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton. G. Cook after Richard James Lane. 1848. Right: Rosina Anne Doyle Bulwer Lytton (née Wheeler), Lady Lytton (1802-1882). Engraving by John Jewell Penstone after Alfred Edward Chalon. 1852. Both courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

If failure to provide a suitably elaborate memorial to his beloved King disappointed Jerdan, it was only the beginning. 1836 was to prove an emotionally roller-coaster year. The volatile marriage of his friends Edward and Rosina Bulwer came to an embittered end in April, when they formally separated after Rosina had raided her husband’s Albany apartments, publicly accusing him of entertaining his mistress there. The fall-out continued for many years, Rosina becoming ever more hysterical and abusive. As one marriage ended, another was just about to begin. Jerdan’s second daughter, Mary Felicity Dawn (whom Hogg had wanted to marry off to his nephew) was twenty-two years old. She met Edward Rawdon Power, three years older. With a marriage looming, and the need to keep up a suitably lavish lifestyle, at least until the ceremonies were over, Jerdan was seriously pressed for money. In January he asked Longmans for the funds he was owed, but received an unsatisfactory note that the book-keeper had “not yet made any progress in the account.” A few days later, on 18 January 1835, he approached Bentley in a more ingratiating tone than he had hitherto adopted:

The great kindness you expressed the other morning has seduced me to ask a favour which I sure if not inconvenient you will grant. The family matters I mentioned pulls my pursestrings hard and there is little in it, and it is of consequence to me to go through with arrangements in a rather liberal style. Well, by the enclosed [probably the letter from Longmans], you may guess that my friends are in no hurry with the quarterly dividends, and they are not called on to send the accounts in till the beginning of February. If you could therefore till then (say a month hence) be my banker from sixty to a hundred pounds and the more the better, I will send you my faithful cheque for it payable at that time. I told the girls of your kind intents and they say you are a nice man and was (sic) very kind to them at Hastings.

This was not the first letter Jerdan was forced to write asking for a loan, and was by no means the last. From this time on, his fortunes declined rapidly, but for now, the crucial thing was to keep up appearances until Mary was safely married. Bentley seems to have assented, as on 7 March Jerdan added a note to a business letter, telling him, “Tomorrow from 1-3 o’clock there will be a breakfast on table at 21 Grosvenor Street for any friends after the marriage ceremony. You would be welcome.” (One would hope so, as it was Bentley’s money paying for the breakfast!) The following day Mary and Edward Power were married at St George’s, Hanover Square, a short stroll from the new Literary Gazette offices where the wedding breakfast was held. The couple moved out to Ceylon where their son Edmund was born in 1842, in the palace at Candy of Sir Robert Wilmot Horton, the Governor of Ceylon, to whom Power was Private Secretary. Power rose to senior appointments in the Ceylon Civil Service, becoming Assistant Colonial Secretary and Government Agent of Candy. He edited one of the earliest periodicals in Ceylon, starting the quarterly magazine,The Ceylon Miscellany in which Mary took a great interest. Power introduced a system of shorthand to Ceylon, and also seemed to have been a good athlete, with “a very expressive face and a large head with curly black hair” (Journal of the Dutch Burgher Union of Ceylon January 1934, No. 3 – with thanks to Michael Gorman. This article includes a photograph of Power.).

On, 23 May 1836, a few weeks after the wedding, Jerdan wrote a personal note to the Governor, asking him and Lady Horton to be kind to his daughter: “She has been a home bird all her days till now, and must feel, as I shall do, the more grateful for any attention you are good enough to bestow upon her” He sent a copy of Sir George Back’s ourney to the Arctic Sea as a token of his esteem. His letter, dated 23 May, brought him to Horton’s notice as someone who could act as his agent, and would be pleased to do anything for the man who could make his daughter’s new life more pleasant. This, of course, was never spelled out.

Horton had a long history of passionate pamphleteering and campaigning on pauperism and emigration, seeing mass emigration as a solution to poverty and overpopulation at home, and a shortage of labour in the colonies, mainly in Canada; he had strong pro-Catholic views, which made him unpopular in some circles. He had been made Governor of Ceylon in 1831 and served until 1837, overseeing the final abolition of slavery in the country and the development of a free press. In November 1836, shortly after Mary and Edward Power’s arrival in Ceylon, Horton wrote a long letter to Jerdan explaining that he had erroneously entrusted all his writings to be published by his Bookseller, Mr Lloyd. The books had not succeeded because Horton had refused to allow them to be advertised and Lloyd thus had no means of making them known. He told Jerdan that although he had contributed articles to the Quarterly Review, he had fallen out with John Murray which was why he had turned to Lloyd. He suggested to Jerdan that maybe Longmans would be interested in republishing his works. He now wanted Jerdan to arrange publication of Letters from the Dead, correspondence he had received from eminent men, including several Bishops, on the topic of poverty in Ireland. His instructions were detailed and verbose, discussing Notes and Appendices, a ‘Motto’ and a dedication and a long ‘Prefatory Chapter’. He promised to send the manuscript in December, so that it should arrive in England in April, and be published in June. He gave the project into Jerdan’s hands: “I name no other person because you must be far better acquainted than I am as to expediency of selection” (Derbyshire Record Office, D3155/WH2824). He gave Jerdan the name of his solicitors, but nowhere in his long letter did he mention or suggest that Jerdan would receive any remuneration for the arduous tasks he expected of him, from re-writing, editing, finding a publisher, rearranging the title page and negotiating the terms of payment to Horton.

In February 1837 Horton sent the original of his book, noting changes, deletions and additions not yet ready. He bade Jerdan get a copy of a Government Report of a Committee on Emigration of 1827 and make substantial extracts from this, although a few days later, by the next ship, he had changed his mind and the Report was to be published in full. “The Table of Contents must, I am sorry to say, be drawn up in England” – presumably another task Jerdan was supposed to undertake gratis. Another month passed and Horton sent an urgent note instructing Jerdan to omit a certain passage from a letter to the Bishop of Limerick, because “it may perhaps be considered objectionable by the friends of the late Bishop to have it published”. However, he wanted it extracted and sent to another correspondent, enclosing a covering letter which he told Jerdan to “read and act upon”. This tacit assumption that Jerdan would jump to his command reflected Horton’s obsessive passion for his causes, oblivious to the fact that Jerdan had other tasks to perform, like running his weekly journal. Jerdan however, would have been in no position to refuse the Governor anything, reliant as the young Powers were on his good will. No book by Horton with the title of Letters from the Dead seems to have been published among the plethora of pamphlets, books and letters with which he deluged politicians and public alike.

Not long after his daughter’s marriage, Jerdan embroiled himself in a major occurrence which made news in The Times and doubtless, much discussion amongst his friends. In 1834, Maclise volunteered, at the request of Crofton Croker who was also a member of the Committee of the Literary Fund, to paint a portrait of Sir John Soane in recognition of his “liberal patronage”. When completed in May 1835 it was framed and hung on the walls of the Committee Room. As far as the Committee was aware Soane had seen and approved the portrait. However, in November it was intimated to the Committee, verbally, that Soane was dissatisfied with the picture, “deeming it a libel and caricature,” and after long debate it was resolved to take the problem to Maclise (Times, 25 May 1836.). He proved willing to take back the portrait, as Soane had not indicated any desire to have it. The Committee wrote officially to Soane to explain the situation, as did Maclise, but neither received any response.

in a letter of 25 March 1836 John Britton took up the cudgels on Soane’s behalf, telling Jerdan that he had been hurt by language used by Dilke, Foss, and Barham at a meeting of the Literary Fund; if there was a repetition, Britton would resign in favour of some other Society who would treat him better. “I shall be compelled to bring forward Soane’s poor portrait again – I wish you could prevail on Maclise to give up his unfinished daub for the fine specimen from Lawrence – Sir John will not live or die in peace with the Society unless it be exchanged – he is violent on the subject” he told Jerdan (Bodleian Library MS. Eng. lett. d. 113, f64). At the Fund’s Committee meeting in March “a person claiming to represent Soane” (namely John Britton) announced that unless Soane “obtained the picture immediately and unreservedly he would withdrawn his patronage from the institution, without an intended bequest and appeal to the public” (Soane Organisation Newsletter No. 14, Spring 2007). On behalf of the Literary Fund W.C. Taylor sent letters of 13 and 25 May 1836 The Times denying that he was ‘one of a Radical faction’ and providing a long account of the affair, which absolved himself of any responsibility. This spokesman reported that he intended to table a motion marking the Committee’s notice of such a threat. However, “on the Saturday night before my motion could be discussed, a Mr Jerdan gained admission to the rooms and destroyed the picture.” He had in fact slashed it to ribbons. In an effort to pre-empt the inevitable furore, Jerdan wrote to The Times on 11 May, putting a light gloss on events: Soane had become older since his flattering earlier portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence, and disliked his present appearance, "sans teeth, sans taste", depicted by Maclise. Soane wished the Maclise portrait returned, and would present the Fund with the one by Lawrence, making this a condition of his future benefaction. Jerdan wrote that many agreed to

humour the veteran architect and return the picture. but Radicalism and Opposition creeps in everywhere. A certain faction stoutly resisted the proposal…when lo! A certain literary reviewer and member of the Council of the Fund well known for his social kindness and humanity as well as his heedless eccentricities, put an end to all contention by entering the Committee Room, and cutting the caricature of Sir John (as the latter considered it) in pieces with his penknife! The Radical faction are again in arms and are taking secret counsel together whether the said summary settler of contentions has not committed an act of felony which may subject him to being hanged!

Taylor’s first furious reaction was to loudly deny Jerdan’s accusation: “I am not a Radical and that I belong to no faction”. As for the felony charge, he had taken legal advice and merely meant that illegal entry and wilful destruction were felonious acts. In his letter to The Times of 13 May Taylor protested, “The few observations I made have been strangely perverted into an anxiety to fix a charge of felony on Mr Jerdan; I feel too much respect for that gentleman on public and private grounds to dream of any such thing.” However, Taylor wished the public to know the story to prove that the Literary Fund would not “stoop to accept money by the sacrifice of principle”, by which he may have meant that they would spurn any further gifts from Soane if they were conditional on having the portrait destroyed or returned to him.

There are no surviving diaries of Soane for 1836, so it is not possible to know from that source whether he asked Jerdan to act on his behalf to destroy the picture or whether Jerdan acted on his own initiative. That Jerdan had pre-determined his act, and it had not been impulsive, was mentioned by Charles Macready. On reading the account of Jerdan’s act of destruction in the Morning Chronicle, Macready noted in his diary for 10 May 1836 that, when visiting his house at Elstree, Jerdan had expressed his intention to destroy the picture and Macready also stated that Soane “has been absurdly and tetchily desirous of destroying that too faithful record of his personal appearance.” However, the archives of the Literary Fund are rather more informative than Jerdan’s own memoir, which treats the affair jocularly. At the Committee Meeting of 11 May 1836 Jerdan explained his motives for having destroying the picture a few days earlier (Archives of the Royal Literary Fund. British Library, M1077/125). He then absented himself from the meeting, leaving behind a letter to be read out, deemed sufficiently important by the Society to be copied into the Minutes Book. In this he paid tribute to the generosity of Sir John Soane as a benefactor and Vice President of the Literary Fund, and to the “young and rising Artist of the highest talents” who had volunteered to make the portrait. Jerdan pointed to the failure of the Committee to submit the portrait “for the approbation of Sir John Soane in the first instance”, especially as it was to honour him. What had been intended as a compliment was in fact an object of “strong aversion and disgust” to the subject.

“Our dilemma was complete” Jerdan went on. The Committee could not affront the Painter, nor did it wish to upset Sir John, who was of an advanced age. Jerdan complained that “One portion of the Committee looked one way, and another the contrary way to get as best we could out of this perplexity, none expressing a desire to retain the portrait”, but all wishing the cause of division to be removed. This he had taken upon himself to do, he explained, but only after consulting the artist first. Referring to Maclise in high-flown language extolling his “liberality which belongs to true genius”, Jerdan told the Committee that the painter’s desire was to contribute to the interests of the Literary Fund, and if destroying his work achieved this end, he agreed that it should be done, and for this “he is entitled to the ever-lasting thanks of the Literary Fund Society”. Having done his best to ensure that the artist was exonerated from any censure, Jerdan concluded by acquiescing that “In the hope of doing a great good, I am sensible that I have boldly ventured to do no small wrong”. If he was forgiven, he would be “highly gratified”, and if censured, would instantly resign from the Committee, but loving the Fund as he did, would continue to work for it in a private capacity. Jerdan’s submission was followed by a brief note from Maclise, addressed to Nichols, Senior Registrar of the Literary Fund, noting that it had been at Nichols’s house that he had discussed the matter with Crofton Croker, a member of the Committee, telling Croker that disposal of the portrait was acceptable to him, if it was in the Society’s interest. Maclise believed that Jerdan had been told this by his good friend Croker, and had acted accordingly.

The anti-Jerdan faction of the Committee, fronted by Messrs Woodfall and Duncan, immediately gave notice of a motion which was discussed the following week. They moved that Jerdan’s conduct be referred to a public meeting of Literary Fund members, but this motion was defeated. Dr Taylor proposed a Resolution acknowledging that Jerdan’s act was “wholly unjustifiable in itself” but that no dangerous precedent had been established. As Soane had disliked the portrait and the artist had agreed to its destruction no further action should be taken. The Committee carried this Resolution unanimously, so Jerdan was “off the hook” for his escapade.

Jerdan himself related only that the Literary Fund’s newly appointed Secretary, whose election he had supported, was a young Irishman named Cusack P. Roney, (later Sir), who, on the night of the destruction, was enjoying an evening of ballet at the Opera House. He was intercepted by Jerdan, who showed him a strip of canvas which had been the eyes of Soane’s portrait. This had the instant effect of Roney leaving the ballet to remonstrate with him. Roney was understandably furious and threatened Jerdan with vengeance, for what Jerdan himself later called a “half-crazy deed”. The episode was possibly why Roney stayed in post for only a year. Perhaps he did not want to be associated with an institution which harboured such a hot-head. Eventually the furore died down and an unrepentant Jerdan made fun of the episode when he came to write his memoirs, quoting a ‘squib’ about the affair:

Ochone! Ochone!

For the portrait of Soane!

Jerdan! You ought to have let it alone,

Don’t you see that instead of “removing the bone

Of contention,” the apple of discord you’ve thrown?

One general moan,

Like a tragedy groan,

Burst forth when the picturecide deed became known.

When the story got blown,

From the Thames to the Rhone,

Folks were calling for ether and Eau de Cologne,

All shocked at the want of discretion you’ve shown.

If your heart’s not a stone,

You will forthwith atone,

The best way to do that is to ask Mr Rone-

-y to sew up the slits; the Committee you’ll own,

When it’s once stitched together, must see that it’s SOANE*

*Qu. SEWN? – Print. Dev.

[a very Jerdanish pun; 4.402. ‘Ochone’ is a Gaelic expression of sorrow or regret that appears in The Ingoldsby Legends.]

There is a postscript to this act of vandalism: a fragment of Maclise’s portrait of Soane was found in 2006 in the Victoria and Albert Museum (Dorey). The fragment shows Sir John’s thumb, and is accompanied by a note setting out the story of the portrait and its destruction. It has been suggested that the note was by Maclise himself, but this is unlikely as it refers to the Committee “being embarrassed how to act, as sending to Sir John would offend the artist, and withholding it would give umbrage to Sir John”; Maclise may not have referred to himself as “the artist”. (The identification was possible as an etching of the portrait appeared in Fraser’s Magazine in 1836.) Maybe Soane had been told that it was unflattering, as the note indicated that “Sir John being blind or nearly so could not judge of its merits himself.” The etching accompanied No. 75 in Fraser’s ‘Gallery of Literary Characters’. The text called Jerdan “the iconoclast”, teasing him that his action “had not even the merit of originality: the experiment of rejuvenating a tough old subject, by the process of cutting up, was long ago tried on Pelias, King of Colchis, at the suggestion of Medea the witch, and was not found to answer”. The article chided Soane for forgetting his own indebtedness to charity at the start of his career, and insisted that literature survives longer than stone and mortar: “a MS may be destroyed, but EDITIONS defy Torch and Turk”.

Undeterred by Jerdan’s notorious activities over the Soane portrait, Thackeray wrote to Jerdan on 22 April 1836, asking, “Will you give me a little puff for the accompanying caricatures? As to their merits, being a modest man, I am dumb; but that is no reason why my friends should be silent – Besides this is my first appearance before the public and I trust that my wages and my character will improve, by the judicious praise which I hope to receive from you” (Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection, The New York Public Library 223652B.) He declined Jerdan’s invitation to the Garrick, saying he had “better keep the six guineas.” The Literary Gazette was often the first public appearance of writers who subsequently became well-known, even famous, a legacy for which Jerdan was solely responsible. Also undeterred by the Soane incident was Richard Bentley, who asked Jerdan to promote his election to the Literary Fund. Jerdan agreed to do so, but warned Bentley that objections might be raised by one of the members to yet another publisher, “as he thought there were more than a fair proportion of them in the Committee.” Bentley was elected to the Committee in November 1836.

The well-known historical novelist G.P.R. James wrote on 12 November 1836 to ask a favour of Jerdan, to review a friend’s book: “I am anxious too to get a review pretty early in the Gazette because as you well know there are many of our good critical friends that will abuse the book first because it is written by a lady, and secondly because she is a friend of mine. I who am an abomination unto them!” He complained of having lost Jerdan’s Grosvenor Street address, so was forced to write to “your inhospitable office in Wellington Street, where I think it is a rule to take in nothing un-post paid.” That old problem of postage was still relevant, but James sweetened his complaint by repeating his previous invitations to Blackheath: “there is a bed and knife and fork, a bottle of claret and a hearty welcome at your service” (Bodleian Library MS. Eng. lett. d. 113, f261). Making most literary quarrels seem quite tame was the enraged reaction of the Hon. Grantley Berkeley to an adverse review of his novel in Fraser’s Magazine. He brutally attacked the publisher, injuring him seriously. On hearing this Maginn, who had written the review, accepted Berkeley’s challenge to a duel, which both survived.

In May 1836 Jerdan dropped the prefix “London” from the Literary Gazette title, responding to changes in the law which no longer required him to publish two separate editions, one for London and the other for the provinces and overseas.

Jerdan’s editorship of the journal had given him access to virtually anyone he wished to see in all walks of life , even now as the Literary Gazette declined in influence and circulation. His circumstances were getting “cold and colder”, initiated by the reduction to half price of the Athenæum, and also the rise and affordability of popular novels, so that long extracts in the Gazette were no longer so important. Mary Russell Mitford noted the changes afoot, writing to a friend, “Do you ever see the London weekly literary journal called the Athenæum. It is the fashionable paper now, having superseded the Literary Gazette. It has such a circulation that, although published at the small price of fourpence the income derived from it by the proprietor is said to be more than £4000 per annum” (Quoted Marchand 73, who notes that the Athenæum had given a glowing encomium to Mitford’s latest work, but her estimate of income was probably wrong, as Dilke was putting profits back into the business.) Jerdan tried to put a good face on his problems, and Planché recalled in his memoirs, “His buoyant spirits enabled him to bear up against ‘a sea of troubles’ which would have overwhelmed an ordinary man. Mr Moyes, his printer, a ‘canny Scot’, being asked by a mutual acquaintance, ‘Has our friend Jerdan got through his difficulties?’ characteristically exclaimed, ‘Difficulties! I never knew he was in any!’” (Stoddard 81). In this respect Jerdan had inherited his father’s easy-going laid-back attitude to life.

With his fortunes going downhill, Jerdan would have been cheered to see Foster’s Cabinet Miscellany by Theodore Foster, published in 1836. The chapter on weekly periodicals naturally featured the Literary Gazette as the oldest of these. He had no compunction in discussing the money Jerdan was rumoured to be making, noting that some said he got £1000 a year for the editorship, others thought £800, plus a share of the profits. These, he said, at one time averaged £5000 per annum, and were still very considerable. He explained how business was done: “Contributors receive a written order for the amount of their remuneration from Mr Jerdan on Messrs. Longman and Co. who immediately pay it….literary men have received as high as one guinea per column, or twenty-four guineas per sheet.” Foster put the Literary Gazette’s circulation for many years at over 5000 a week; a special issue containing the review of “A Key to Almack’s” pushed it to 7000. The Gazette was still a “good property”, he felt. The remainder of the section praised Jerdan for bringing on individual authors, naming L.E.L. and Robert Montgomery. He insisted that charges against the Literary Gazette for its “want of independence” were unjust: three or four out of every five of Colburn’s books, he calculated, “have been most liberally condemned”. If Jerdan were guilty at all, it was of an unconscious “feeling of friendship towards the authors rather than from solicitations or understood wishes of any publishing house”. As if to prove his point, Foster added a note to reassure his readers that he had no “personal inducement” to speak in support of Jerdan; indeed, the Literary Gazette’s review of his own last work “exceeded the limits of temperate criticism”. Jerdan needed all the champions he could muster at this challenging time, and Foster’s voluntary contribution must have been most welcome.

Readers were attracted to serialised novels, and the year 1836 saw the start of one of the greatest of these, published by Chapman and Hall. At the end of March the first instalment of Pickwick Papers appeared, priced at one shilling with a print run of a thousand copies. Sales were modest, so the next instalment a month later was reduced to five hundred copies, but the third instalment rose again to one thousand. Jerdan was as entranced as everyone else with Dickens’s tale. He was especially charmed by the story of Sam Weller in the fourth episode, extracting this and reprinting it in the Literary Gazette without acknowledgement. His friendship with Dickens was linked to their mutual support of the Literary Fund, so he felt that he could write to the author about the new serial, and urged him to develop Sam Weller’s character “largely – to the utmost”, advice which Dickens accepted in good part and which proved to be so important for Pickwick’s success. Sales soared and orders for back numbers poured in. According to the Penguin edition of Pickwick, Dickens deleted an aside in Chapter 11 of later editions, about an “unflattering portrait of Sir John Soane destroyed by Soane’s friend and subsequently Sam Weller’s champion, William Jerdan.” Jerdan could thus be hailed as one who made Pickwick famous, thereby ensuring the gratitude and success of Dickens.

At the same time Dickens had a job as reporter on the Morning Chronicle, and between the appearance of the third and fourth episodes of Pickwick had to cover the trial of Lord Melbourne. Taking advantage of Dickens’s rising popularity, Bentley offered him a contract for two novels, with no time limit. Dickens requested a higher fee and it was agreed that he would receive five hundred pounds for each; the contract was signed in August. Another contract between the two was signed in November. Dickens agreed to edit the new Bentley’s Miscellany for twenty pounds a month, plus twenty guineas for contributing sixteen pages of his own writing, the copyright belonging to Bentley. This new task, with income from the Chronicle and Pickwick, raised his income to almost £800 a year, but he quickly resigned from the Chronicle to concentrate on the Miscellany and his own writing. Jerdan was to contribute several articles to the Miscellany in the years ahead.

In low spirits for a variety of reasons, the actor William Macready dined alone at the Garrick at the beginning of May, and noted that Jerdan, amongst others, came to his table to greet him. Calling on John Forster, Macready learnt that Jerdan had done as he had threatened, and destroyed the Soane portrait. By 3 June, Jerdan had put the portrait debacle behind him, and dined at the Garrick, where he and Forster were toasted by Macready as “uniform and earnest supporters of the cause of the drama…Jerdan made a good speech, if at all to be questioned, only for his too much kindness to me” (Macready).

Jerdan Begins a Third Family

Jerdan’s domestic life was still weighing heavily upon him when he met a woman named Mary Maxwell, and began a new affair that resulted in a large family. Nothing is known about her, save that she was born in Somerset. At nineteen, she was thirty-five years younger than Jerdan and eight years younger than his daughter Frances-Agnes. When exactly this new relationship started is unsure, as records are unavailable. However, Mary Maxwell became pregnant and in about 1836 gave birth to Marion, nicknamed Mop, who was quickly followed by Matilda Maxwell Jerdan (originally named Stewart), and familiarly known as Tilly. The two girls were soon followed by a son, Henry.

With this third family to support it is astonishing that Jerdan kept going both financially and physically, but on the surface at least his work for the Literary Gazette, his other writings, meetings, dinners and activities, kept up the same pace as always. Nothing survives to indicate his feelings at this time – or any time – so one can only speculate how he managed his extremely complicated life. Mary and her children would most likely have been a secret at this point, but Frances must have known about her husband’s financial and moral dilemmas, if she was at all interested in him any longer. They would have had to put a good public face on their union, at least until Mary’s marriage to Edward Power had been safely accomplished.

Whether Landon was aware of Jerdan’s new affair cannot be known; it raises the question as to whether Jerdan embarked on his new relationship as a backlash to Landon’s albeit failed engagement to John Forster, or whether Landon engaged, and then disengaged herself to Forster, and contracted marriage with the man she was about to meet, in the face of what she may have seen as Jerdan’s abandonment of her in favour of Mary Maxwell. With rumours flying about Landon’s alleged affairs with several men, and Jerdan’s (now-revealed) affairs with at least Landon, Maxwell, and maybe others, the atmosphere was a hothouse of jealousy, passion and deception. All this took its toll on her. Henry Vizetelly saw her around this time and recalled,

I am ignorant of what L.E.L.’s pretensions to beauty may have been in the days when she captivated the too amorous Maginn after the susceptible Jerdan had been enamoured of her; but when I saw her on one occasion no very long time afterwards, prior to her ill-fated marriage, she was certainly most unattractive, and I failed to recognize any resemblance to the flattering portrait that formed the frontispiece to one of her books. The recollection I have preserved is of a pale-faced, plain-looking little woman with lustreless eyes, and somewhat dowdily dressed, whom no amount of enthusiasm could have idealized into a sentimental poetess. [126]

Bibliography

Collins, A. S. The Profession of Letters – a Study of the Relations of Author to Patron, Publisher and the Public 1780-1832. London: George Routledge & Sons, 1928.

Cruse, Amy. The Englishman and his Books in the Early Nineteenth Century. London: George Harrap & Co., 1930.

Duncan, Robert. “William Jerdan and the Literary Gazette.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Cincinnati, 1955.

Fisher, J. L. Victorian Periodicals Review 39, No. 2 (2006): 97-135.

Gettmann, Royal A. A Victorian publisher, A Study of the Bentley Papers. Cambridge: University Press, 1960.

Hall, S. C.Retrospect of a Long Life. 2 vols. London: Richard Bentley & Son, 1883.

Hall, S. C. The Book of Memories of Great Men and Women of the Age, from personal acquaintance. 2nd ed. London: Virtue & Co. 1877.

Jerdan, William. Autobiography. 4 vols. London: Arthur Hall, Virtue & Co., 1852-53.

Jerdan, William. Men I Have Known. London: Routledge & Co., 1866.

The Letters of Letitia Elizabeth Landon. Ed. F. J. Sypher, Delmar, New York: Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints, 2001.

Landon, L. E. Letitia Elizabeth Landon: Selected Writings. Ed. Jerome J. McGann and D. Reiss. Broadview Literary Texts, 1997.

Lawford, Cynthia. “Diary.” London Review of Books. 22 (21 September 2000).

Lawford, Cynthia. “Turbans, Tea and Talk of Books: The Literary Parties of Elizabeth Spence and Elizabeth Benger.” CW3 Journal. Corvey Women Writers Issue No. 1, 2004.

Lawford, Cynthia. “The early life and London worlds of Letitia Elizabeth Landon., a poet performing in an age of sentiment and display.” Ph.D. dissertation, New York: City University, 2001.

Marchand, L. The Athenæum – A Mirror of Victorian Culture. University of North Carolina Press, 1941.

Mackenzie, R. S. Miscellaneous Writings of the late Dr. Maginn. Reprinted Redfield N. Y. 1855-57.

McGann, J. and D. Reiss. Letitia Elizabeth Landon: Selected Writings. Broadview Literary Texts, 1997.

Pyle, Gerald. “The Literary Gazette under William Jerdan.” Ph. D. dissertation, Duke University, 1976.

Sadleir, Michael. Bulwer and his Wife: A Panorama 1803-1836. London: Constable & Co. 1931.

St. Clair, W. The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period.

Sypher, F. J. Letitia Elizabeth Landon, A Biography. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints, 2004, 2nd ed. 2009.

Thrall, Miriam.Rebellious Fraser’s: Nol Yorke’s Magazine in the days of Maginn, Carlyle and Thackeray. New York: Columbia University Press, 1934.

Timbs, J. Club Life of London. London: Richard Bentley, 1866.

Last modified 2 July 2020