Instead of joining the Gold Rush to California in the Far West, young Henry James (1843-1916) was taken in an easterly direction from his home in New England to the Old World, to the cultural capitals of Europe – London, Paris and Geneva, and also Bonn. Henry James Sr, his wife Mary, their five children (William, Henry, Garth Wilkinson, Robertson and Alice) and French nanny, Annettte Godefroi, embarked on the S. S. Atlantic at New York docks on 27 June 1855. The transatlantic crossing was not without considerable risks: on one occasion the non-arrival of that same steamer had caused such extreme anxiety among the public that its safe arrival was announced to "so a huge and pronounced roar of relief" at the curtain fall in the theatre (Small Boy 144). The Arctic and the Pacific both went down on that route. The crossing lasted eleven days, and the family finally disembarked, on 8 July, on the west coast of Lancashire, at Liverpool, then the second largest seaport in Great Britain after London.

Henry James Sr wanted his children (particularly his sons) to experience a "sensuous education". He had already formulated his plan to Ralph Waldo Emerson as early as August 1849 when he wrote that he was gravely pondering "whether if would not be better to go abroad for a few years with them, allowing them to absorb French and German and get a better education than they are likely to get here" (Life 38). So James's first great European adventure had begun at the age of twelve and, apart from a short interlude back in America, he was not to return until late September 1860. Of all the places he visited, Paris and London were the great settings for his boyhood education, the "formative forces" in his "aesthetic evolution" (Small Boy 163, 165). Both were exciting and fascinating and so full of history. Queen Victoria was firmly on the throne, and France was ruled by the self-styled Emperor Napoléon III and Spanish-born Empress Eugénie.

But James's "sensuous education" commenced in England, where, after a lengthy journey by coach and horses from Liverpool to London, he recalled a hotel room with a "great fusty curtained […] medieval four-poster" (Small Boy 144) bed and his first intense act of seizing the experience of the atmosphere both inside and outside. Young James was ill and feverish – he thought he had malaria – and the sensations he was experiencing were heightened, most probably, by his sickness.

When James first arrived in Paris in July 1855, an ambitious slum clearance and urban development programme was underway under the guidance of the Paris préfet Georges Eugène Haussmann (1809-1891). The whole city was an education for the twelve-year-old. He spent hours in the great rooms of the Louvre – they were "educative, formative, fertilising" (Small Boy 182) – and acquired a sense of "reconstituted" history through such paintings as Delaroche's The Execution of Lady Jane Grey and Edward V and the Duke of York in the Tower. James discovered the paintings of Thomas Couture (1815-1879), in particular The Romans of Decadence, a work that had earned him the accolade of "the new Veronese" when, at the Paris Salon of 1847, it was likened to the Italian artist's huge canvas The Marriage at Cana.

Géricault's Raft of the Medusa. Click on images to enlarge them.

The young boy was awestruck by Géricault's Raft of the Medusa depicting dying and terrified men abandoned on a raft after a shipwreck in a storm on the West coast of Africa: it was "the sensation, for splendour and terror of interest" (Small Boy 182).

For a short time James attended, mornings only, a small experimental school, the Institution – or Pension – Fezandié (named after the owners) in the rue Balzac, in the 8th arrondissement in central Paris. It was, he recalled, "the oddest and most indescribable" of establishments, "a recreational, or at least a social, rather than a tuitional house!" It was chosen by James's father, one of "many free-spirits of that time", on account of its promotion of the utopian ideas of Charles Fourier (1772-1837): it must have been based on one of his experimental "phalanxes" or self-sufficient units, a kind of co-operative style of living. But young James coped with its eccentricities and indeed relished the place that he recalled as "positively gay – bristling [...] and resonant" (Small Boy 190-91). His French improved rapidly and he adapted easily to a cultured European life style.

Elisabeth Rachel Félix. Edmond-Aimé-Florentin Geffroy (1804-1895). 1855. Click on image to enlarge it.

Paris theatres, like those of London, provided James with a permanent source of enjoyment and delight. Rachel, "alive, but dying" – she died on 3 January 1858 – Mademoiselle Georges, Mademoiselle Mars, all famous actresses of the time, performed to wild acclaim (Small Boy 186). He haunted the Café Foyot of the old Paris, and walked the streets "across the Champs-Élysées to the river, [...] over the nearest bridge and the quays of the left bank to the Rue de Seine" (Small Boy 176), browsing in second-hand bookshops and print-shops.

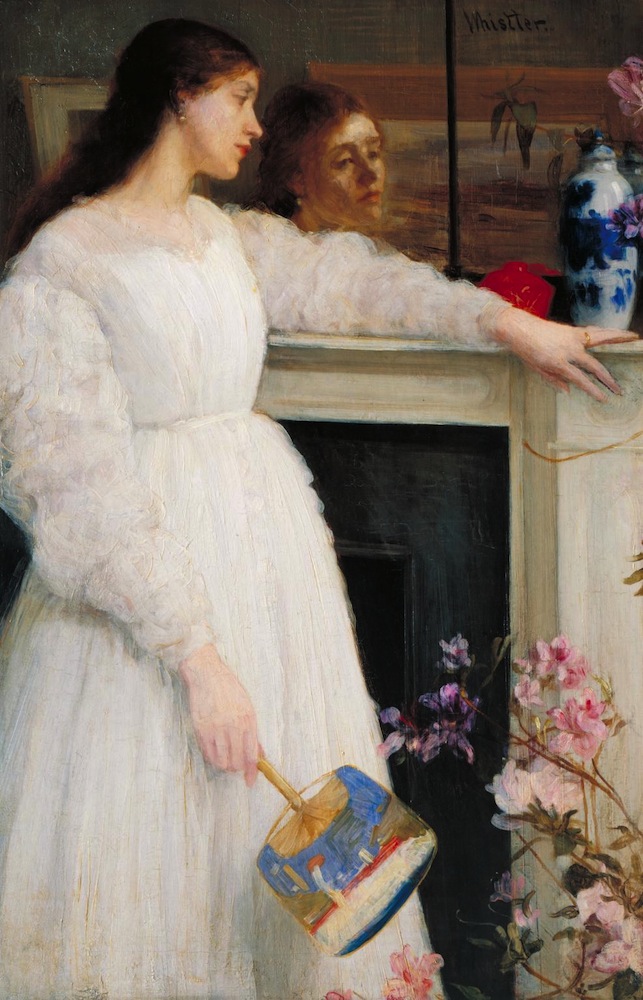

This was the city that was to become the second home to fellow American painter and dandy, James McNeill Whistler. Twenty-two-year-old Whistler had arrived for the first time in Paris on 2 November 1855, after spending the previous month in London. The great Paris show, the Exposition Universelle – Edward Burne-Jones and Morris had been there in July and admired English paintings by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Charles Collins – was a magnet for both James and Whistler. However, these two great Europeanised Americans did not meet each other until much later, according to Edel for the first time at a dinner chez the society hostess Christina Stewart Rogerson, in 1878/9 (Life 226). First impressions were not very favourable, for the novelist described his fellow-countryman as "a queer but entertaining creature" (Life 226).

James's most memorable experiences of London around 1855-1856 were in the world of the theatre and art. He had at that early age eclectic tastes and was not subjected to parental censorship of any kind. That was in keeping with his parents' broadminded views and desire for their son to have a wide education. He experienced almost every kind of entertainment, from popular shows to Shakespeare. Albert Smith's dioramas, at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, of his ascent of Mont Blanc attracted huge crowds who enjoyed being terrorised as they re-lived the dangers experienced on the climb. James was there, having his senses charmed by the "big, bearded, rattling, chattering, mimicking Albert Smith" (Small Boy 165). whose presence in Chamonix in August 1851 had so offended John Ruskin. James's thirst for the spectacular was assuaged by Charles Kean's production of Shakespeare's Henry VIII, a "momentous date" in his life. Memories of that prodigious, lavish revival, of such historical and archaeological accuracy, with colours akin to stained-glass windows, remained with him for a long time.

Left: Autumn Leaves. Sir John Everett Millais Bt PRA (1829-96). 1855. City Art Galleries, Manchester, Right: The Scapegoat. William Holman Hunt. 1854-1856. Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight (Liverpool).

He delighted in the National Gallery and Royal Academy displays, particularly Millais's Autumn Leaves and his prodigious Blind Girl and the awesomeness of Holman Hunt's Scapegoat. The very word Pre-Raphaelite had a particular resonance for him, and "that intensity of meaning, not less than of mystery, that thrills us in its perfection" (Small Boy 164-65). Years later, James would enter more fully their world and become acquainted with some of these artists in person (Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Morris).

Returning to America, after the excitement of this European experience, seemed dull. Desultory law studies at Harvard in 1862-1864 did not provide James with inner satisfaction. The "muse of prose fiction" had a stronger appeal and James began to publish literary reviews and short stories.

James was twenty-six years old when he renewed contact with Victorian England in 1869. This was the first of several visits leading to his decision to take up more permanent residence and eventually become a British citizen in 1915. After disembarking at Liverpool docks from the S. S. China on a cold, windy day, Saturday 27 February, after a ten-day transatlantic voyage, the unaccompanied bachelor spent the night at the Adelphi Hotel before heading straight for London where, after staying a few days at Morley's Hotel in Trafalgar Square, he took lodgings at 7 Half-Moon Street, off Piccadilly.

His detailed letters to his family in America recount the extremely busy social life into which he plunged. He engaged intensely with London life, absorbing, observing, getting as close as possible to the metropolis. Many may have considered him to be a dilettante – the same charge that was to be erroneously levelled at Marcel Proust (1871-1922) – but his thirst for continuous social intercourse, in which he revelled, was also the essential foundation, the gathering of material for his becoming a great novelist. James was a relatively wealthy man who could have travelled by brougham or taken a victoria, but instead, he deliberately chose to walk "for exercise, for amusement, for acquisition". Most effective and productive were his nocturnal London walks: "above all I always walked home at the evening's end", he wrote in his preface to The Princess Casamassima, "when the evening had been spent elsewhere, as happened more often than not". This 1869 sojourn, in which James really discovered himself and his vocation, was of defining importance. His imagination reacted swiftly to the many impressions that "sought an issue" in the birth of a book. The habit of walking with "one's eyes greatly open" that he acquired resulted in an almost symbiotic relationship with people and places: "a mystic solicitation, the urgent appeal, on the part of everything, to be interpreted and, so far as may be, reproduced." Ideas for his novels might come from a stray suggestion, a word, even a vague echo could start a train of thought in his imagination as though it had been pricked by a sharp pin: "one's subject is in the merest grain, [...] the seed [...] transplanted to richer soil." He jotted down these echoes in his notebooks where they matured.

One may wonder how James was able to enjoy such a fruitful social life so quickly. He had an engaging personality, certainly, but he also had the right contacts. Of these, the most important was the American writer, scholar, art historian and art collector Charles Eliot Norton, who became Professor of Fine Art at Harvard in 1875, a post he held until 1898. Norton was a sensitive, sophisticated man, profoundly Europeanised – he regularly stayed in Switzerland, Italy, France and England – and was regarded by his lifelong friend and confidant John Ruskin as having a "genius for friendship" (36.xciii). Norton became an ardent enthusiast of Ruskin, Edward Burne-Jones and their circle, and did much to promote their work in America. So great was his advocacy of Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites that at times it appeared to be counterproductive and caused some of his students to rebel. James had been greatly indebted to Norton for his support for his early literary endeavours. As joint editor (with James Russell Lowell) of the North American Review, Norton had accepted for publication in October 1864 James's "first fond attempt at literary criticism": this was a review of Essays on Fiction, a collection of reviews by the English political economist Nassau William Senior (1790-1864). Norton subsequently invited James to become a regular contributor. James remained immensely grateful to the "invaluable" Norton (Selected Letters 22), personal friend of so many eminent literary and scientific figures of the day – Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Thomas Carlyle, Charles Darwin, Charles Dickens, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Leslie Stephen. James received many invitations to dine at the Nortons, then (in 1869) residing for a while in an old Rectory at Keston, in Kent. He was also warmly welcomed by other members of the Norton family, by Charles's two sisters Grace (1834-1926) and Jane (1824-1877), his wife Susan, née Sedgwick (1838-1872), brother-in-law Arthur Sedgwick (1844-1915), and sister-in-law Sara Sedgwick (1839-1902) who married Darwin's son, William. The entire family devoted a great deal of time to James, ensuring that he was embedded in an important artistic and literary network that extended far beyond anything he could have imagined.

University College London, the Wilkins Portico. The main building, by William Wilkins, in partnership with J.P. Gandy-Deering, was completed in 1827. Reginald Turnor describes it as "half-brother to the National Gallery" (32). The dome had to be recast by T.L. Donaldson in 1848. Photograph by Jacqueline Banerjee.

Barely ten days after arriving in England, James was taken by the Nortons (after dining with them) to University College London, to hear Ruskin for the very first time. The subject of his lecture, on the evening of Tuesday, 9 March 1869, was "Greek Myths of Storm", particularly the legends of Athena and Bellerophon. James's immediate reaction was brief but positive: "I enjoyed it much in spite of fatigue", he wrote to his sister Alice, adding, "but as I am to meet him someday thro' the N's, I will reserve comments" (Selected Letters 22).

The next day, James was plunged into the world of the Pre-Raphaelites and the burgeoning Arts and Crafts movement, and more Greek myths in poetry. "My crowning day", was how he resumed Wednesday, 10 March – his first encounter with William Morris. At 4.30 p.m, he was taken by Norton and "ladies" to Morris's home, showroom, fabrique and company office at 26 Queen Square, Bloomsbury. His first impression of Queen Square was unfavourable: "an antiquated ex-fashionable region, smelling strong of the last century, with a hoary effigy of Queen Anne in the middle". For James, Morris had been first and foremost an imaginative poet whose lengthy works, The Life and Death of Jason and The Earthly Paradise he had favourably reviewed in American journals in 1868. Now it was a revelation to discover that Morris was principally "a manufacturer of stained glass windows, tiles, ecclesiastical and medieval tapestry altar-cloths, and in fine everything quaint, archaic, pre-Raphaelite – and I may add exquisite". James was impressed not only by the quality and design of Morris's work – "so handsome, rich and expensive (besides being articles of the very last luxury) [...] superb and beautiful" – but also by his method of working: "He designs with his own head and hands all the figures and patterns used in his glass and tapestry and [...] works the latter, stitch by stitch with his own fingers – aided by those of his wife and little girls" (Selected Letters 22-23).

James fell under the spell of Jane, Morris's thirty-year-old wife. He was ecstatic: "Ah, ma chère," he wrote to his sister Alice, "such a wife! Je n'en reviens pas – she haunts me still" (23). So often in moments of heightened emotion, James interjects fragments of French expressing his own linguistic duality and the strength of his feeling for French culture. Jane, complex, magnificent and hard to define, was the embodiment of the Pre-Raphaelite ideal:

A figure cut out of a missal – out of one of Rossetti's or Hunt's pictures – to say this gives but a faint idea of her, because when such an image puts on flesh and blood, it is an apparition of fearful and wonderful intensity. It's hard to say [whether] she's a grand synthesis of all the pre-Raphaelite pictures ever made – or they a "keen analysis" of her – whether she's an original or a copy. In either case she is a wonder. [23]

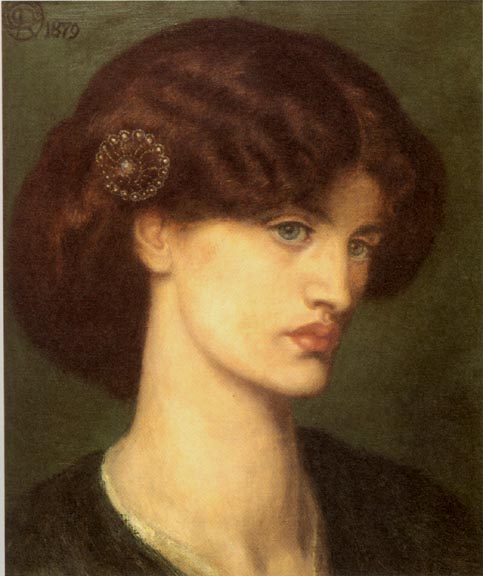

Left: Beatrice, a Portrait of Jane Morris. Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). Signed with monogram and dated 1879 at the upper left. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Peter Nahum. Middle: Algernon Charles Swinburne. William Bell Scott. 1860. Oil on canvas. 47 3/4 x 31.7 inches. Right: The Ballad of Oriana. William Holman Hunt. 1857. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In his penetrating description focussing on her dress, face and hair, he captures, in that same letter, some of the mystery of her sexuality: her remote, detached, immobile exterior conceals her hidden desires and charged sensuality. She is both medieval ("a figure cut out of a missal") and modern. Yet her identity and sexuality are blurred: her eyes are likened to those of Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909), and her mouth resembles Hunt's engraving of Oriana for Alfred Tennyson's (1809-1892) The Ballad of Oriana. Her striking resemblance to Swinburne is apparent in Dante Gabriel Rossetti's watercolour of the redheaded, flamboyant young poet in 1861. The predominant Pre-Raphaelite colours of purple and black frame accentuate her sexless exterior, her pallor, sadness and longing for her lover, Dante Gabriel. She seems sickly, unhealthy, "lean" rather than slim, wearing a dress of some "dead" material:

Imagine a tall lean woman in a long dress of some dead purple stuff, guiltless of hoops (or of anything else, I should say,) with a mass of crisp black hair heaped into great wavy projections on each of her temples, a thin pale face, a pair of strange, sad, deep, dark Swinburnish eyes, with great thick black oblique brows, joined in the middle and tucking themselves away under her hair, a mouth like the "Oriana" in our illustrated Tennyson, a long neck, without any collar, and in lieu thereof some dozen strings of outlandish beads – in fine Complete. [23]

Hanging on the wall was Rossetti's "large nearly full-length portrait of her", possibly The Blue Silk Dress. It was "so strange and unreal", wrote James, "that if you hadn't seen her, you'd pronounce it a distempered vision, but in fact an extremely good likeness" (23).

The unhealthy, anorexic picture of Jane – an appearance that belied her strength for she outlived her husband by nearly twenty years and died in 1914 – is reinforced by her retreat, after dinner, into a corner of the apartment, where she lounged unsociably on a sofa, passive, silent and supposedly suffering: a "medieval woman with her medieval toothache". The couple's incompatibility becomes more apparent: Morris was, James observed, "extremely pleasant and quite different from his wife". He related the incongruous and almost unreal scene to his sister, contrasting Morris's demonstrative reading aloud of his mythological poetry (an appropriate link with Ruskin's lecture of the previous evening) with the stillness and remoteness of Jane:

There was something very quaint and remote from our actual life, it seemed to me, in the whole scene. Morris reading in his flowing antique numbers a legend of prodigies and terrors (the story of Bellerophon, it was), around us all the picturesque bric-a-brac of the apartment (every article of furniture literally a 'specimen' of something or other,) and in the corner this dark silent medieval woman with her medieval toothache.

He described Morris as "short, burly and corpulent, very careless and unfinished in his dress", with "a very loud voice and a nervous restless manner and a perfectly unaffected and business-like address". James continued: "His talk indeed is wonderfully to the point and remarkable for clear good sense. He said no one thing that I remember, but I was struck with the very good judgment shewn in everything he uttered. He's an extraordinary example, in short, of a delicate sensitive genius and taste, served by a perfectly healthy body and temper. All his designs are quite as good (or rather nearly so) as his poetry" (23-24.)

D. G. Rossetti's House on Cheyne Walk. Photograph by Jacqueline Banerjee.

In a letter of 20 June 1869 to the artist John La Farge, James related that he had met Rossetti, introduced by Norton who took him to his Cheyne Walk studio "in the most delicious melancholy old house at Chelsea on the river" (Selected Letters 38). It was packed with curios, cabinets, ornaments, mirrors, furniture, strange pets, and exotic, lush, erotic paintings and drawings inspired by his relationships with Fanny Cornforth (his model), Elizabeth Siddal (his wife from 1860 who died of an overdose of laudenum two years later), Jane Burden Morris and Swinburne. But James was disappointed, for the promise of such a "home and haunt" did not match the reality of the occupant. Forty-one-year-old Rossetti struck him as "unattractive" and "horribly bored": this may have been due to one of his bouts of depression (he would attempt suicide in 1872). As regards his portraits, "they were all large, fanciful portraits of women, of the type que vous savez, narrow, special, monotonous, but with lots of beauty and power" (38).

Norton arranged for James to be invited (along with some members of the Norton family) to dine with Ruskin at his home at 163 Denmark Hill, in what was then a small, leafy village, known as the "Belgravia of the South", to the south of London. The visit took place sometime after the lecture on Greek Myths and before 26 April 1869 when Ruskin left for the continent. James had the opportunity to experience the life of a well-off, comfortable, middle-class household consisting of Ruskin's frail, increasingly deaf and partially blind eighty-seven-year-old widowed mother, Margaret, her nurse and companions, servants, housekeeper and gardeners. The large, detached, three-storey-villa, with a lodge and a keeper who turned away unwelcome callers, was set in seven acres of land, part of it, to the rear, being meadow, flower and vegetable gardens. By 1869, many of the rooms were more like art galleries, crammed with dozens of works by Turner (including the now celebrated canvas Slavers throwing overboard the Dead and Dying - Typhon coming on), Samuel Prout, David Roberts, Copley Fielding and others that Ruskin and his father (until his death in 1864) had collected avidly for many years. So huge was the collection that Ruskin decided to sell forty-one of his Turners and other works at a Christie's sale that took place on 15 April, leaving their destiny and value to the vagaries of an auction.

Slave Ship. [Full title: Slavers Overthrowing the Dead and Dying -- Typho[on]n Coming On. J. M. W. Turner. Oil on Canvas. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

"R[uskin] was very amiable", James wrote to his American friend, the painter John La Farge, "and shewed his Turners. The latter is assuredly great" (39). But the painting in the Ruskin collection that James most enjoyed was a portrait by Titian – "an old Doge, a work of transcendent beauty and elegance, such as to give one a new sense of the meaning of art" (Life 95). This was the Portrait of the Doge, Andrea Gritti (now in The National Gallery, London), an oil on canvas then attributed to Titian, but since 1931 considered to be the work of Vincenzo Catena. At the Whistler-Ruskin trial in 1878, it was taken into court as evidence of what a properly finished work should be: "a perfect specimen [...] an arrangement in flesh and blood" was how Burne-Jones, one of the witnesses for the defendant, described it.

But much more revealing was James's letter to his mother in which he records his impressions of Ruskin:

Ruskin himself is a very simple matter. In fact, in manner, in talk, in mind, he is weakness, pure and simple. I use the word, not invidiously, but scientifically. He has the beauties of his defects; but to see him only confirms the impression given by his writing, that he has been scared back by the grim face of reality into the world of unreason and illusion, and that he wanders there without a compass or guide – or any light save the fitful flashes of his beautiful genius. The dinner was very nice and easy, owing in a great manner to Ruskin's two charming young nieces who live with him – one a lovely young Irish girl with a rich virginal brogue – a creature of a truly British maidenly simplicity – and the other a nice Scotch lass who keeps house for him.

Ruskin had seemingly given the impression, perhaps by the abundance of familiar expressions he used to address them, that the two young women were his nieces. The girl with the Irish accent was Lily Armstrong (a former pupil at Winnington School, near Northwich, in Cheshire, with which Ruskin developed close links): she was the daughter of Serjeant Armstrong, MP for Sligo, and was a guest at the house. The "nice Scotch lass" would have been Joan Agnew (later Severn), then aged twenty-three. She was a very distant cousin of Ruskin and had come from Wigtown, in Scotland, to Denmark Hill in 1864 to be a companion to the widowed Margaret Ruskin whom Joan called "Auntie".

Ruskin's House at Denmark Hill. Source: Volume 35 of the Library Edition. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Lunch with the former cleric, writer, critic and mountaineer Leslie Stephen (1832-1904) marked the beginning of a fruitful and life-long relationship. As influential editor of the Cornhill Magazine, Stephen accepted James's short story Daisy Miller "with effusion" (it was published in two numbers of the Cornhill Magazine in 1878). This controversial story of Daisy, an unconventional and independent young American in Europe, whose defiance of certain mores coupled with a degree of naivety contribute to her untimely death in Rome, was hugely popular and established James's fame on both sides of the Atlantic. A long-time admirer and reviewer of George Eliot's works, he finally met the revered writer one Sunday in April (1869), escorted there, as he recalled in The Middle Years, "by one of the kind door-opening Norton ladies".

James's activities, however, were not solely London based. He toured many English counties, and spent several weeks, for health reasons, in Great Malvern, the attractive market and spa town with the ruins of a fine Abbey, nestling in the Malvern Hills in Worcestershire. It was the presence of the English countryside, recalling in a not un-Proustian way memories of childhood reading that he carried back with him to America as he sailed on the Scotia on 30 April 1870. He recalled "elm-scattered meadows and sheep-cropped commons and the ivy-smothered dwellings of small gentility, and high-gabled, heavy-timbered, broken-plastered farmhouses, and stiles leading to delicious meadow footpaths and lodge-gates leading to far off manors – with all these things suggestive of the opening chapters of half-remembered novels, devoured in infancy."

The "pleasure of cathedral-hunting" occupied much of his time in the spring of 1872, when he haunted and explored the old cathedral cities of Chester and its Roman ruins, Lichfield, Exeter, Wells and Salisbury, and savoured what he called, in a way redolent of Ruskin, the "tone of things".

Back in Paris of the Third Republic in 1876, James encountered many literary figures – Gustave Flaubert, Alphonse Daudet and the Russian writer Ivan Turgenev. He went on numerous excursions to Normandy, Picardy, the Marne, and published travel sketches about the ancient cathedral towns of Rheims, Laon, Soissons and Rouen. Other essays were devoted to Chartres and Étretat, and a longer sketch was entitled "From Normandy to the Pyrenees". He returned to London in late 1876, decided to settle, and took accommodation at 3 Bolton Street, off Piccadilly, two streets away from his previous lodgings in Half-Moon Street.

Norton had been instrumental in opening doors for James in 1869: now that role was taken over, to some extent, by another Europeanised and much travelled compatriot, the historian Henry Brooks Adams (1838-1918), son of the American diplomat and author Charles Francis Adams and grandson of John Quincy Adams, 6th President of the USA. James was immensely grateful to Adams and expressed his thanks to his long-standing friend in a letter of 5 May 1877: "Your introductions rendered me excellent service and brought about some of the pleasantest episodes of my winter."

With astuteness and rapidity, the engaging, increasingly cosmopolitan, budding writer, on the verge of being an expatriate, cultivated an ever-widening circle of interesting and influential people – leading literary figures, politicians, scientists, aristocrats – often through contacts made at prestigious London clubs. Massachusetts-born historian and diplomat, John Lothrop Motley (1814-1877), put James on the honorary list of the Athenaeum, a club he was to "frequent and prize". How greatly James delighted in the history of that prestigious club in Pall Mall! To his father he proudly declared: "I am writing this in the beautiful great library of the Athenaeum Club." Occupying seats around him were "Herbert Spencer, asleep in a chair [...] and a little way off is the portly Archbishop of York with his nose in a little book".

The Athenæum Club by Decimus Burton. 1824. Waterloo Place and Pall Mall, London. Photograph July 2005 by George P. Landow.

James needed the stimulation of intellectual company in order to work. He had expressed this need to his parents a few years earlier: "What I desire now more than anything else, and what would do me more good, is a régal of intelligent and suggestive society, especially male. But I don't know how or where to find it. [...] I chiefly desire it because it would, I am sure, increase my powers of work." He was now revelling in such company. In a detailed letter of 10 July 1877 to his elder brother William, then a lecturer in comparative anatomy at Harvard, he painted a lively, frank and often amusing picture of many of his social activities. On Sunday 8 July 1877, he dined en famille with Darwin's "bulldog", the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley (1825-1895). He dined, uncomfortably on one occasion at the home of Mme Van de Weyer (the wealthy English lady née Bates, wife of Silvain Van de Meyer, Belgian Minister in London) at "a big luscious and ponderous banquet, where [he] sat between the fat Mme V. de W. and the fatter Miss ditto".

Richard Monckton Milnes, 1st Baron Houghton (1809-1885). Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London NPG Ax17806

One of James's most influential and stimulating acquaintances at this time was Richard Monckton Milnes (Lord Houghton from 1863), with whom Ruskin had breakfasted in 1844. Monckton Milnes had the reputation of knowing everybody in society. He was a flamboyant, temperamental character who enjoyed the domineering and controlling role of patron of budding writers – provided they accepted his conditions. He befriended Swinburne and secured the poet laureateship for Tennyson, his friend and contemporary at Trinity College Cambridge. Milnes was renowned for his trenchant wit, malicious gossip and sexual excesses. His library of erotica at Fryston Hall, Yorkshire, was reputed to be unrivalled. He was a close friend of Captain (later Sir) Richard Burton (1821-1890) – also an acquaintance of Ruskin – traveller, poet (perhaps manqué) but an accomplished translator of erotic, oriental literature including The Kama Sutra, The Perfumed Garden, and the Arabian Nights. Not only was "the bird of paradox" a collector of books, but a collector of people. James was invited to his literary breakfasts, lunches and dinners, and even became a guest at Fryston Hall, his country house in his constituency.

At the same time, James was busy writing and publishing articles about his first-hand experiences of London life: the crowds at events in the social calendar – the Oxford and Cambridge boat race, Derby Day on the Epsom Downs, and people in parks. He reported on the Grosvenor Gallery exhibition in his article "The Picture Season in London, 1877". Among the exhibits were works by Burne-Jones – his six panels depicting The Days of Creation, and his oil painting The Beguiling of Merlin: the latter James admired as "a brilliant piece of rendering [that] could not have been produced without a vast deal of 'looking' on the artist's part", thereby helping to establish Burne-Jones's reputation.

Left: Three panels from The Days of Creation. Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University. Right: The Beguiling of Merlin (also known as Merlin and Vivien. 1874. Oil on canvas. 73 x 43 3/4 inches. Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight.

The Grosvenor would soon be known as the gallery in which Whistler's controversial painting, Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, had first been exhibited and which became the subject of a cause célèbre following Ruskin's libellous comments.

Left: Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket. James Abbot McNeill Whistler (1834–1903). c. 1875 Oil on panel, 23.7 × 18.3 inches (60.3 × 46.4 cm). Collection: Detroit Institute of the Arts number 46.309. Middle: James Abbot McNeill Whistler by Paul Rajon. Drawing. Source: Pennell and Courbin, Concerning the Etchings of Mr. Whistler. Right: Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl. James Abbot McNeill Whistler. 1864. Oil on canvas, 76.5 x 51.1 cm. Tate Britain, Accession N03418. Bequeathed by Arthur Studd, 1919.

It was almost mid-July 1877, and the London season was drawing to a close. Henry James felt exhausted after his usual hectic round of invitations. After seven months in London, he was longing to get away, to escape to France or Italy, to collect his thoughts and to "get into some quiet rural spot and at work". Life as an inveterate diner-out was beginning to take its toll: he needed to harness his experiences and devote time to sustained writing. His plans to go to Spain had been thwarted by news of the troubled political situation. Perhaps he would go to Dieppe or along the Normandy coast for a few weeks. But momentary doubts remained, nevertheless, about the direction of his work: "I don't even know whether to begin work upon a novel I have projected for next year." In spite of his professed feelings of uncertainty, novels were germinating in his mind: The Europeans was published in 1878, followed by Washington Square in 1880 and The Portrait of a Lady in 1881.

But just before James finalised his decision to go abroad, he received a letter from America that would have an impact both on his immediate plans and the course of his life and writing.

Last modified 12 March 2020