Tom Brown's Schooldays, which praises the role of sports in Public School education, describes a world of boys and young men enjoying the "legitimate pastimes of cricket, fives, bathing, and fishing," and one of the things that make Tom a school-boy hero is his accomplishment in becoming captain of an important team. Hughes here briefly sounds a note much like those found throughout so many reminiscences of Public School graduates who regale the reader with tales of once-glorious once-young athletes. Hughes, however, take a very different — and one might say more mature — approach: at the same time that he conveys the pleasure and glory of schoolboy athletic achievement, encouraging his young readers to enjoy every moment of it, he also emphasizes that such accomplishments and the fame they bring are transient — and properly so. Note how in the following passage, he places the reader in a particular moment, makes us feel present, and then moves these events into what will be the past:

It was a fine November morning, and the close soon became alive with boys of all ages, who sauntered about on the grass, or walked round the gravel walk, in parties of two or three. East, still doing the cicerone, pointed out all the remarkable characters to Tom as they passed: Osbert, who could throw a cricket-ball from the little-side ground over the rook-trees to the Doctor's wall; Gray, who had got the Balliol scholarship, and, what East evidently thought of much more importance, a half-holiday for the School by his success; Thorne, who had run ten miles in two minutes over the hour; Black, who had held his own against the cock of the town in the last row with the louts; and many more heroes, who then and there walked about and were worshipped, all trace of whom has long since vanished from the scene of their fame. And the fourth-form boy who reads their names rudely cut on the old hall tables, or painted upon the big-side cupboard (if hall tables and big-side cupboards still exist), wonders what manner of boys they were. It will be the same with you who wonder, my sons, whatever your prowess may be in cricket, or scholarship, or football. Two or three years, more or less, and then the steadily advancing, blessed wave will pass over your names as it has passed over ours. Nevertheless, play your games and do your work manfully — see only that that be done — and let the remembrance of it take care of itself.

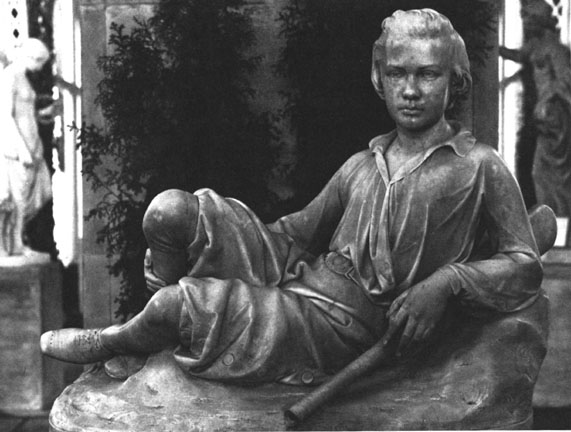

Waiting for His Innings and The Rowers both by Joseph Durham.

[Click on thumbnails for larger images]

Some critics have argued that an elegaic tone permeates much of the finest Victorian literature — yearning for lost childhoods that may not have been as idyllic as remembered or yearning for lost ages, such as Carlyle's, Pugin's, and Ruskin's middle ages, that also might not have been all that they were cracked up to be. Certainly, In Memoriam and The Idylls of the King record personal loss, as does Ruskin's Praeterita, which is in part a record of dead friends and relations. Hughes here strikes a note closer to Hopkins's "Spring and Fall" or Housman's "To an Athlete Dying Young." But his chief advice is, enjoy things proper to youth while you can, or as he puts it, "The elms rustled, the sparrows in the ivy just outside the window chirped and fluttered about, quarrelling, and making it up again; the rooks, young and old, talked in chorus, and the merry shouts of the boys and the sweet click of the cricket-bats came up cheerily from below."

References

Hughes, Thomas. Tom Brown's Schooldays. Electronic version from Project Gutenberg produced by Gil Jaysmith and David Widger.

Last modified 21 November 2024