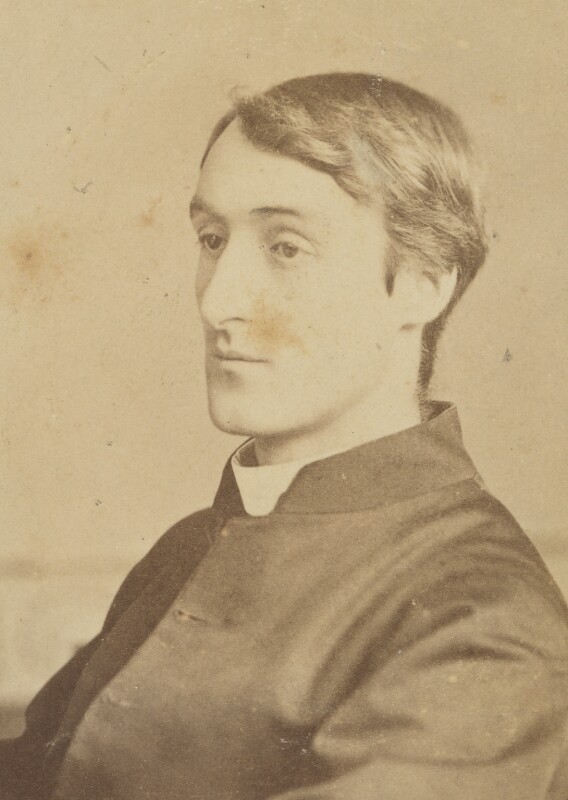

Hopkins's albumen carte-de-visite, 1880, by

Forshaw & Coles, © National Portrait Gallery,

by kind permission (NPG P455).

Gerard Hopkins was born July 28, 1844, to Manley and Catherine (Smith) Hopkins, the first of their nine children. His parents were High Church Anglicans (variously described as "earnest" and "moderate"), and his father, a marine insurance adjuster, had just published a volume of poetry the year before.

At grammar school in Highgate (1854-63), he won the poetry prize for "The Escorial" and a scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford (1863-67), where his tutors included Walter Pater and Benjamin Jowett. At one time he wanted to be a painter-poet like D. G. Rossetti (two of his brothers became professional painters), and he was strongly influenced by the aesthetic theories of Pater and John Ruskin and by the poetry of the devout Anglicans George Herbert and Christina Rossetti. Even more insistent, however, was his search for a religion which could speak with true authority; at Oxford, he came under the influence of John Henry Newman. (See Tractarianism.) Newman, who had converted from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism in 1845, provided him with the example he was seeking, and in 1866 he was received by Newman into the Catholic Church. In 1867 he won First-Class degrees in Classics and "Greats" (a rare "double-first") and was considered by Jowett to be the star of Balliol.

The following year he entered the Society of Jesus; and feeling that the practice of poetry was too individualistic and self-indulgent for a Jesuit priest committed to the deliberate sacrifice of personal ambition, he burned his early poems. Not until he studied the writings of Duns Scotus in 1872 did he decide that his poetry might not necessarily conflict with Jesuit principles. Scotus (1265-1308), a medieval Catholic thinker, argued (contrary to the teachings of St. Thomas Aquinas) that individual and particular objects in this world were the only things that man could know directly, and then only through the haecceitas ("thisness") of each object. With his independently-arrived at idea of "inscape" thus bolstered, Hopkins began writing again.

In 1874, studying theology in North Wales, he learned Welsh, and was later to adapt the rhythms of Welsh poetry to his own verse, inventing what he called " sprung rhythm." The event that startled him into speech was the sinking of the Deutschland, whose passengers included five Catholic nuns exiled from Germany. The Wreck of the Deutschland is a tour de force containing most of the devices he had been working out in theory for the past few years, but was too radical in style to be printed.

From his ordination as a priest in 1877 until 1879, Hopkins served not too successfully as preacher or assistant to the parish priest in Sheffield, Oxford, and London; during the next three years he found stimulating but exhausting work as parish priest in the slums of three manufacturing cities, Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow. Late in 1881 he began ten months of spiritual study in London, and then for three years taught Latin and Greek at Stonyhurst College, Lancashire. His appointment in 1884 as Professor of Greek and Latin at University College, Dublin, which might be expected to be his happiest work, instead found him in prolonged depression. This resulted partly from the examination papers he had to read as Fellow in Classics for the Royal University of Ireland. The exams occured five or six times a year, might produce 500 papers, each one several pages of mostly uninspired student translations (in 1885 there were 631 failures to 1213 passes). More important, however, was his sense that his prayers no longer reached God; and this doubt produced the "terrible" sonnets. He refused to give way to his depression, however, and his last words as he lay dying of typhoid fever on June 8, 1889, were, "I am happy, so happy."

Apart from a few uncharacteristic poems scattered in periodicals, Hopkins was not published during his own lifetime. His good friend Robert Bridges (1844-1930), whom he met at Oxford and who became Poet Laureate in 1913, served as his literary caretaker: Hopkins sent him copies of his poems, and Bridges arranged for their publication in 1918.

Even after he started writing again in 1875, Hopkins put his responsibilities as a priest before his poetry, and consequently his output is rather slim and somewhat limited in range, especially in comparison to such major figures as Tennyson or Browning. Over the past few decades critics have awarded the third place in the Victorian Triumvirate first to Arnold and then to Hopkins; now his stock seems to be falling and D.G. Rossetti's rising. Putting Hopkins up with the other two great Victorian poets implies that his concern with the " inscape" of natural objects is centrally important to the period; and since that way of looking at the world is essentially Romantic, it further implies that the similarities between Romantic and Victorian poetry are much more significant than their differences. Whatever we decide Hopkins' poetic rank to be, his poetry will always be among the greatest poems of faith and doubt in the English language.

Last modified 1988