oth in theory and in practice George Eliot's realism welcomed the idealization

of character. "Paint us an angel, if you can," urges the narrator of Adam Bede,

"paint us yet oftener a Madonna. . ." (17: 270). And as if to heed his own advice,

he thrice associates Dinah Morris with the angel at Christ's sepulchre in Adam's

new illustrated Bible ((10:162, 14:208, 51:319). By the same token, Milly Barton

is "a large, fair, gentle Madonna" (2:24), and Lucy Deane in The Mill on

the Floss has "a face breathing playful joy, like one of Correggio's

cherubs" (VI, 9:267).2 As these examples suggest, George Eliot habitually

idealized her characters by associating them with sacred and heroic history

painting and classical sculpture. Her work well exemplifies what Jean Hagstrum

calls "the unshakeable association that has existed between literary idealization

and ideal form in the graphic arts" (Sister Arts, p. 8). This chapter

will discuss the rationale for George Eliot's pictorial idealization of character,

and relate her techniques to the revival of typological iconography in the nineteenth-century

visual arts. Particular attention will be paid to Eliot's characteristic ambivalence

toward such idealization as it is expressed in Middlemarch, and to her

complex resolution of that ambivalence in the double plot of Daniel Deronda.

oth in theory and in practice George Eliot's realism welcomed the idealization

of character. "Paint us an angel, if you can," urges the narrator of Adam Bede,

"paint us yet oftener a Madonna. . ." (17: 270). And as if to heed his own advice,

he thrice associates Dinah Morris with the angel at Christ's sepulchre in Adam's

new illustrated Bible ((10:162, 14:208, 51:319). By the same token, Milly Barton

is "a large, fair, gentle Madonna" (2:24), and Lucy Deane in The Mill on

the Floss has "a face breathing playful joy, like one of Correggio's

cherubs" (VI, 9:267).2 As these examples suggest, George Eliot habitually

idealized her characters by associating them with sacred and heroic history

painting and classical sculpture. Her work well exemplifies what Jean Hagstrum

calls "the unshakeable association that has existed between literary idealization

and ideal form in the graphic arts" (Sister Arts, p. 8). This chapter

will discuss the rationale for George Eliot's pictorial idealization of character,

and relate her techniques to the revival of typological iconography in the nineteenth-century

visual arts. Particular attention will be paid to Eliot's characteristic ambivalence

toward such idealization as it is expressed in Middlemarch, and to her

complex resolution of that ambivalence in the double plot of Daniel Deronda.

Not all Victorian novelists believed in the compatibility of the ideal and the real. Trollope, for example, assumed that the terms are antithetical. Transvaluing Reynolds's famous contrast between Italian and Dutch painting, Trollope contended in The Last Chronicle of Barset that the High Renaissance [73/74] art of Italy depicts what is unreal:

We are, most of us, apt to love Raphael's madonnas better than Rembrandt's matrons. But though we do so, we know that Rembrandt's matrons existed; but we have a strong belief that no such woman as Raphael painted ever did exist. In that he painted . . . for Church purposes, Raphael was justified; but had he painted so for family portraiture he would have been false." [London: Smith, Elder, (1867), II, 84:383]

This conception of realism was very different from George Eliot's. She believed that Raphael's madonnas sometimes belong in family portraiture, and she pointedly denied that the ideal is antithetical to the real. "Any real observation of life and character must be limited, and the imagination must fill in and give life to the picture," she told John Blackwood in 1861 (Letters, III, 427).

Eliot agreed with G. H. Lewes's argument, in his important essay on "Realism in Art" (1858), that the opposite of realism is not idealism but falsism. Lewes illustrates the compatibility of idealism, with realism by citing Raphael's Sistine Madonna:

In the figures of the Pope and St. Barbara we have a real man and woman, one of them a portrait, and the other not elevated above sweet womanhood. Below, we have the two exquisite angel children, intensely childlike, yet something more, something which renders their wings congruous with our conception of them. In the never-to-be-forgotten divine babe, we have at once the intensest realism of presentation, with the highest idealism of conception: the attitude is at once grand, easy, and natural; the face is that of a child, but the child is divine . . . we feel that humanity in its highest conceivable form is before us.... Here is a picture which from the first has enchained the hearts of men, which is assuredly in the highest sense ideal, and which is so because it is also in the highest sense real — a real man, a real woman, real angel-children, and a real Divine Child; the last a striking contrast to the ineffectual attempts of other painters to spiritualize and idealize the babe — attempts which represent no babe at all. [pp. 493-94.]

The Leweses valued highly the ideal realism of High Renaissance painting, and George Eliot strove to create a similar effect in many parts of her own fiction.6 [74/75]

R. Smirk's illustration of "The Marys at the Sepulchre" (detail) was engraved by W. Sharp and published on 16 July 1791 by Thomas Macklin of Fleet Street. Figure 6 in print version

Eliot was of course no Christian, but her idealization had a rationale in the secular religion of humanity which replaced her Evangelicalism. This humanism rejected Christian theology but sought to retain the ethics, emotional culture, and social bonding of the older religion. Feuerbach, whose Essence of Christianity strongly influenced Eliot on these points, argued that since the Christian god is a projection of mankind, mankind itself should be worshipped in a religious spirit. Christian devotion should be transferred to secular subjects, and human experience should be venerated and sanctified.7 George Eliot favored this redirection of emotion, and promoted it in her fiction by associating her characters with sacred and heroic visual] art. Thus she attempted to hallow Romola's experience by visualizing her moral growth as a progression from "The Unseen Madonna" to "The Visible Madonna" to "the Holy Mother with the Babe, fetching water for the sick" in a plague-stricken village (43:131, 44:141, 68:406).8 Feuerbach himself suggested a didactic and affective rationale for literary pictorialism when he defined imagination as the "type-creating [bildliche], emotional, and sensuous" part of the human mind, and argued that "man, as an emotional and sensuous being, is governed and made happy only by images, by sensible representations."9

Raphael, Sistine Madonna Gemäldgalerie Alte Meister, Dresden. Figure 1 in print version.

George Eliot took something of a liberty when she rendered Feuerbach's term bildliche as "type-creating." But her translation points up one important element of traditional Christian thought which she sought to preserve and secularize in her religion of humanity: the concept of types. George Eliot's pictorial idealization may be viewed in the context of efforts by other nineteenth-century artists to redefine typological symbolism so that it might serve the religious and aesthetic needs of the age. Typological symbolism attracted many of the best minds of the period because it offered a way of conferring spiritual meaning upon the representation of phenomenal experience? of affirming the existence of design while yet respecting the integrity of history. Strictly speaking, a type is an Old Testament prefiguration of a New Testament truth. It is not a vehicle of allegory; a type retains its identity as a historical reality at the same time that it foreshadows the divinely ordained event which fulfills it.10 The Victorians often used the term more loosely, however, to denote [75/76] any exemplary moral or religious norm which finds successive incarnations in history.

In the visual arts the revaluation of typological symbolism was a sign of dissatisfaction with established conceptions of sacred and heroic history painting. This dissatisfaction had grown steadily since the middle of the eighteenth century; see Paulson, Emblem and Expression, pp. 35-47. In the later eighteenth century, history painters began boldly to combine the inherited motifs of Christian art with scenes of contemporary heroism.12 By the mid-nineteenth century, a creative and nontraditional typological symbolism was widely employed in English painting. Obscure or invented incidents in the early life of Christ were made to foreshadow famous later events, and Christian types were often applied postfiguratively to secular and contemporary situations. Such symbolism is a prominent feature in Pre-Raphaelite painting, where it balances the tendency of empirical realism toward fragmentation and atomism.14

William Holman Hunt, A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Priest from the Persecution< of the Druids. 1849-50. Oil on canvas, 43 3/4 x 52 l/2 in. Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University.

The iconography of the Deposition in Holman Hunt's A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Missionary from the Persecution of the Druids (1850), of the Pieta in Henry Wallis's The Death of Chatterton (1856), of the Madonna and Child in Ford Madox Brown's The Pretty Baa-Lambs (1852) or Take Your Son, Sir! (1857),15 of the emblematic pilgrimage in Millais's The Blind Girl (1856),16 suggests in each case a connection between a concrete historical moment and a recurrent type of spiritual activity.

The Death of Chatterton. Henry Wallis. 1856. Oil on canvas, 24 1/2 x 36 3/4 inches. Collection: The Tate Gallery, London. Not in print version.

George Eliot came to art, then, in an atmosphere congenial to "the notion that Types in their continuing cycles can be found in contemporary reality" (Fletcher, p. 680). Her education had introduced her to the traditional exegesis of biblical types, which was still widespread in nineteenth-century Evangelical circles.18 In Scenes of Clerical Life, Amos Barton finds it difficult to communicate "instruction through familiar types and symbols." Attempting to explain the Christian significance of unleavened bread, he carries the imagination of his audience "to the dough-tub, but unfortunately was not able to carry it upwards from that well-known object to the unknown truths which it was intended to shadow forth" (2:39). In "Janet's Repentance" the residents of Milby "had not yet heard that the schismatic ministers of Salem [the Dissenters' chapel] were obviously typified by Korah, Dathan, and Abiram" (2:60). George Eliot was [76/77] obviously familiar enough with typological thinking to draw upon it for humorous effects.

The novelist often used the word type in connection with the representation of sublime and religious ideas in contemporary art. At Weimar she saw a portrait head of Goethe at seventy which she thought "might serve as a type of sublime old age" (p. 90). Also at Weimar she saw Liszt in concert, and thereafter understood why "the type of Liszt's face seems to haunt [Ary Scheffer] in so many of his compositions." She particularly recalled Scheffer's Die drei Weisen aus dem Morgenlande (1844), a picture "in which he expressly intended to introduce an idealization of Liszt" as one of the three Magi, "gazing in ecstasy at the guiding light above them." She herself thought Liszt looked like "a perfect model of a St. John" or "a prophet in the moment of inspiration" (Essays, p. 98). This kind of idealization, which ennobles without falsifying its subject, and which associates admirable human faces with established Christian exemplars, violates neither George Eliot's atheism nor her conception of realism.

She used the word type even more revealingly when defending her presentation of Mordecai in Daniel Deronda: "The effect that one strives after is an outline as strong as that of Balfour of Burley [in Scott's Old Mortality] for a much more complex character and a higher strain of ideas. But such an effect is just the most difficult thing in art-to give new elements-i.e. elements not already used up — in forms as vivid as those of long familiar types" (Letters, VI, 223). Here is a clear statement of the rationale for the pictorial idealization of character in George Eliot's fiction: she seeks to give the new elements of her religion of humanity in forms as vivid as those of the long familiar types of traditional religious culture.19

Eliot was well aware of the revaluation of typological symbolism in the nineteenth-century visual arts, especially within the German Nazarene and English Pre-Raphaelite movements.20 She began to follow the work of the Pre-Raphaelites in 1852, when she commended Millais's A Huguenot on Saint Bartholomew's Day in May and read the famous essay on "Pre-Raphaelitism in Art and Literature" in the British Quarterly Review for November (Letters, II, 29-30, 48). This essay helped to shape her most basic beliefs about [77/78] the movement: that it represented a salutary return to nature, truth, and realism in art, but that its strengths were sapped by its weakness for medieval ecclesiasticism and archaism.

"Hunt's famous pair of moral pictures." Left: The Light of the World. 1851-53. Oil on canvas over panel, arched top, 49 3/8 x 23 l/2 inches. Keble College, Oxford. Right: The Awakening Conscience. 1851-53. Oil on canvas. 29 1/4 x 21 5/8 inches. Tate Gallery, London. Neither in print version.

Thus Eliot had mixed reactions to the work of her favorite Pre-Raphaelite painter, William Holman Hunt. In 1856 she described him as "one of the greatest painters of the pre-eminently realistic school" (Essays, p. 268), and she remained interested in his work at least until 1864, when she sent to Sara Hennell a sympathetic critique of his Afterglow in Egypt (Letters, IV, 159). But her lack of sympathy with the theistic religious aims of Hunt's painting sometimes made her indifferent or oblivious to the workings of its figural symbolism.21 She had no use for The Light of the World (1853) because "it is too mediaeval and pietistic to be rejoiced in as a product of the present age" (Letters, II, 156). She praised The Hireling Shepherd (1851) for the "marvellous truthfulness" of its landscape (Essays, p. 268), but quite misread the moral iconography of the shepherd and the wench, failing to see that, like Adam Bede, the painting is profoundly critical of false and idyllic notions of pastoral; see John Duncan Macmillan, "Holman Hunt's Hireling Shepherd: Some Reflections on a Victorian Pastoral," The Art Bulletin, 54 (1972), 187-97, and chapter 8, n. 46, below. Her doctrinal antipathy probably accounts for her inability to perceive the similarity between her own mode of didactic symbolism and that of her more orthodox contemporaries.23

She was even less receptive to the typological history painting of the German Nazarenes, which she encountered on her trips to Berlin, Munich, and Rome in 1854-60. She was sympathetic with the early Nazarene revolt against the German neoclassical style, and once compared it (borrowing an argument from the author of "Pre-Raphaelitism in Art and Literature") with Wordsworth's rebellion against eighteenth-century poetic diction. Thus she defended "an early poem of Wordsworth's, or an early picture of Overbeck's" on the ground that "the attempt at an innovation reveals a want that has not hitherto been met" (Essays, pp. 99-100). But Eliot strongly disliked the monumental style of history painting which Nazarene artists and their disciples began to practice in the 1820s and perfected in the 1840s; see Keith Andrews, The Nazarenes: A Brotherhood of German Painters in Rome (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1964), pp. 29, 67. G. H. Lewes was referring to this style when he spoke of "celebrated paintings of the Modern German school . . . in which a great deal is meant and very little executed, full of symbol and historical meaning, which require a long commentary [78/79] before they can be rendered intelligible, and which before and after the commentary leave the emotions untouched and the eye ungratified" ("Realism in Art," p. 497). Because George Eliot's critique of Nazarene history painting is central both to the question of her pictorial idealization of character and to the meaning of Middlemarch, it is worth discussing in some detail.

It has long been recognized that Adolf Naumann, the German painter of the Rome chapters of Middlemarch, represents the Nazarene or revivalist tradition, which was the branch of German Romantic art best known in Victorian England; see William Vaughan, "The German Manner in English Art, 1815-1861," Diss. Courtauld Institute 1977, pp. 18, 25, 35. Naumann is modeled upon two identifiable Nazarenes: Johann Friedrich Overbeck (1789-1869) and Josef von Führich (1800-76). Naumann's link with Overbeck is twofold. First, Naumann portrays Mr. Casaubon in a "picture in which Saint Thomas Aquinas sat among the doctors of the Church in a disputation too abstract to be represented, but listened to with more or less attention by an audience above" (22:332).,/P.

Johann Friedrick Overbeck, The Triumph of Christianity in the Arts. Figure 7 in print version.

Gordon S. Haight has noted the resemblance between this fictive painting and Overbeck's The Triumph of Christianity in the Arts (1840), a picture that George Eliot had hoped to see during her trip to Germany in 1854-55 (Haight, p. 151; fig. 7). Both of these idealized history paintings are patterned after Raphael's Disputa in the Vatican Stanze (see Andrews, The Nazarenes, p. 69). The second link between Naumann and Overbeck is a detail of the costume worn by Overbeck on the day George Eliot visited his Roman studio in 1860 — a connection first noticed in a review of Cross's Life by Joseph Jacobs (George Eliot . . . : Essays and Reviews from the 'Athenaeum ' [London: D. Nutt, 1891], p. 72). The venerable painter had on "a maroon velvet cap, and a grey scarf over his shoulders." On display in Overbeck's studio, the Leweses saw cartoons of The Savior Withdraws from His Followers on the Hill at Nazareth (1857) and Allegory of the Arts (1860). Duly recorded in the novelist's journal (Cross, II,158), these items reappeared eleven years later as "a dove-coloured blouse and a maroon velvet cap" worn by Naumann when the Casaubons visit his studio in Middlemarch (22:327). Having seen the greatest of the Nazarenes in his own milieu, George Eliot knew how to dress a character partly modeled upon him.

Although Overbeck lived to be visited by George Eliot, he was nevertheless too old to be Naumann's sole original. The distinguished Nazarene was already forty in 1829, the year of Dorothea's honeymoon (For 1829 as the year of Dorothea's honeymoon, see Jerome Beaty, "History by Indirection: The Era of Reform in Middlemarch," Victorian Studies, 1 (1957), 173-79). Chronologically, Naumann more closely resembles Josef von Fuhrich, who was born in Bohemia in 1800 and worked under Overbeck in Rome from 1827 to 1829, helping to finish the frescoes [79/80] in the Casino Massimo (see Andrews, p. 51). One of the paintings attributed to Naumann in the novel is modeled upon a painting of Fuhrich's that George Eliot had seen during her own honeymoon trip to Berlin in 1854-55.

Ladislaw tells us that Naumann is painting "the Saints drawing the Car of the Church" (22:326). This processional allegory recalls Führich's The Triumph of Christ. George Eliot saw the painting in Graf Raczinsky's famous collection of modern art, and described it in her journal with a charmingly Dorothean incomprehension of the iconography, which derives from Titian's Triumph of Faith:

Under this picture was one by a Viennese artist [Führich had become Professor of History Painting at Vienna] also shewing a great amount of misapplied power. Jesus sits in a chariot, drawn by a bullock and a lion (I think), Popes in their robes pushing along the wheels, and a saintly female figure — the Virgin, I suppose, sitting opposite him" ["Recollections of Berlin," Beinecke Library; for the iconography, see E. Panofsky, Problems in Titian, Mostly Iconographic, N. Y.: New York U.P., 1969, pp. 58-63].

Josef von Führich, The Triumph of Christ. Museum Narodwe, Poznań. Figure 8 in print version.

The lion and "bullock" are, of course, two of the four evangelists drawing the chariot, and the "Popes" at the wheels are the four fathers of the church, of whom only Gregory wears the papal habit. Dorothea's ignorance of Christian iconography in Middlemarch clearly mirrors a stage in her creator's own education. Nevertheless, George Eliot was almost certainly remembering Führich's Triumphzug when she attributed "the Saints drawing the Car of the Church" to Naumann. She may also have remembered Otto van Veen's Der Triumph der katholischen Kirche in sechs Bildern allegorisch dargestellt, which she might have seen at Munich in 1858; see Verzeichnis der Gemalde in der koniglichen Pinakothek zu Munchen (Munich,1858), pp. 197-200. 36 Vaughan, "The German Manner in English Art," p. 46.

The year of Dorothea's wedding journey was a year of great change in the Nazarene movement. It marked the end of the Roman phase of the movement, which had begun in 1810, when Overbeck first moved to the Eternal City to live and paint in the spirit of late medieval Christianity with his fellows in the Brotherhood of Saint Luke. After the completion of the Casino Massimo frescoes in 1829, the remaining Nazarenes disbanded to various cities in Germany, leaving Overbeck to carry on alone in Rome. By then Nazarene artists were in great demand for the decoration of public buildings and monuments, and the staffing of various academies and art institutes. Official recognition and patronage prompted a change toward a programmatic, didactic, monumental style of art [80/81] suitable to the decoration of cities that had grown culturally ambitious, intensely nationalistic, and historically self-conscious. This later phase of German art, known to George Eliot chiefly through Overbeck's Triumph of Christianity and the fresco cycles in Berlin and Munich of Peter Cornelius and his pupil Wilhelm von Kaulbach, is clearly anticipated by Naumann's theory and practice of history painting in Middlemarch.

George Eliot's critique of Naumann's art involves a sophisticated version of the standard Victorian charge that modern German art contains too much mind and not enough nature. The Leweses thought of the Nazarenes and their followers essentially as Pre-Raphaelites who lacked the saving grace of naturalism. Eliot's principal objection to German monumental art was that its symbolism is insufficiently grounded in an empirically observed and represented order of nature. This tendency to depict things "too abstract to be represented" is suggested by Ladislaw's introduction of Naumann as "one of the chief renovators of Christian Art, one of those who had not only revived but expanded that grand conception of supreme events as mysteries at which the successive ages were spectators, and in relation to which the great souls of all periods became as it were contemporaries" (22:332,326). We are meant to take this vague but grandiose neotypological theory of history painting with a large grain of salt. Idealization must not be confused with Teutonic mystification. (For a different view of Naumann's achievement, see Barbara Hardy, "Middlemarch: Public and Private Worlds," English, 25 (1976), 22.)

Naumann's pictures are open to the same objections that George Eliot made to Wilhelm von Kaulbach's weltgeschichtliche Bilder when she saw them at Berlin and Munich. Kaulbach's "allegorical-historical compositions . . . intended to represent the historical development of culture," she declared, "leave one entirely cold as all elaborate allegorical compositions must do."41 Kaulbach's frescoes employ "a regular child's puzzle of symbolism," she complained to Sara Hennell; "instead of taking a single moment of reality and trusting to the infinite symbolism that belongs to all nature, he attempts to give at one view a succession of events, each represented by some group which may mean 'whichever you please, my dear"' (Letters, II, 454-55). In other words, Kaulbach's symbolism does not sufficiently incarnate the ideal in the real. It [81/82] ignores what Ruskin termed the naturalist ideal, and it violates Lessing's prohibition against representing events separated by time in a single picture; see Laokoon, sec. xviii. The engravings of "mystic groups where far-off ages made one moment" in Mrs. Meyrick's front parlor in Daniel Deronda (20:313) are probably reproductions of modern German history paintings such as Kaulbach's.

First articulated in the 1850s, George Eliot's reaction to Nazarene art remained relatively unchanged. Reappearing in Middlemarch, her critique of the indeterminacy and arbitrariness of German typological symbolism amusingly unites Mr. Brooke's fuzzy response to the "Dispute" with Will Ladislaw's parody of the "Saints." Brooke, echoing Browning's Duke of Ferrara, says to Casaubon: "And we'll go down and look at the picture. There you are to the life: a deep subtle sort of thinker with his forefinger on the page, while Saint Bonaventure or somebody else, rather fat and florid, is looking up at the Trinity. Everything is symbolical, you know — the higher style of art: I like that up to a certain point, but not too far — it's rather straining to keep up with, you know" (34:86). As interpreted by Mr. Brooke, the "symbolical" style of Naumann's "Dispute" affords more delight than instruction.

Ladislaw's parody of the "Saints" likewise stresses the indeterminacy and arbitrariness of its symbolism, but does so more instructively:

"I have been making a sketch of Marlow's Tamburlaine Driving the Conquered Kings in his Chariot. I am not so ecclesiastical as Naumann, and I sometimes twit him with his excess of meaning. But this time I mean to outdo him in breadth of intention. I take Tamburlaine in his chariot for the tremendous course of the world's physical history lashing on the harnessed dynasties. In my opinion that is a good mythical interpretation." Will here looked at Mr. Casaubon, who received this offhand treatment of symbolism very uneasily, and bowed with a neutral air. [22:326-27]

Will's statement is not, as Richard Ellmann and others have assumed, a description of an actual project.43 Rather, it describes a purely imaginary allegory of secular history concocted by Will to parody the symbolic pretensions of Nazarene allegories of church history. Will's fantastic "Tamburlaine" belongs to the same genre as Kaulbach's "allegorical-historical compositions . . . intended to represent [82/83] the historical development of culture." The point of the parody is essentially the same point that Will makes when he accuses Naumann of thinking "that all the universe is straining towards the obscure significance of your pictures" (19:290).

What weakens Naumann's history painting is precisely what vitiates Mr. Casaubon's key to all mythologies. Proceeding from dogmatic Christian preconceptions, both men approach history deductively and categorically rather than inductively and empirically. As a follower of Jacob Bryant's A New System, or an Analysis of Ancient Mythology (1774-76), Casaubon finds his key to all mythologies in the revealed truth of Holy Scripture, and seeks to interpret the pagan mythologies as corruptions of the one true myth.44 Both he and Naumann read the past as a symbolic record of Christian certitudes. Their agreement on the Christian interpretation of myth and history is signified by Casaubon's decision to appear in the "Dispute" and to buy the finished painting. In Scenes of Clerical Life, George Eliot noted the bond between Nazarene art and Anglican sensibilities when she described a clergyman's study in which "a refined Anglican taste is indicated by a German print from Overbeck" ( I 1: 170). One wonders whether she knew that Charles Pusey visited Overbeck in Rome in 1829 (Vaughan, "German Manner in English Art," p. 48).

To associate Naumann with Casaubon in this context is to see how Naumann's career fits the historical pattem of aspiration and failure established by the careers of the major characters in Middlemarch. Naumann's ambition to renovate Christian art is comparable to Casaubon's ambition to find the key to all mythologies. But like the mythographer, the painter is working along lines that future generations will judge to have been misguided and retrogressive. In George Eliot's view, Naumann's achievement belongs to a reactionary eddy in the mainstream progression of nineteenth-century painting toward a Ruskinian naturalism. She had little sympathy with the deliberate imitation of archaic pictorial styles, and less with the attempt to revive medieval Catholicism; thus she once criticized Overbeck for evoking "all the barbarisms of the Pre-Raphaelite period."46 The Nazarene program ran dead against George Eliot's belief in humanistic empiricism and evolutionary development.

Tempering this judgment with a characteristic admixture of [83/84] sympathy, however, Eliot perceived many virtues in the Nazarene movement. She certainly admired the learning, energy, and commitment of its adherents. What she said of Overbeck in 1860 might well be applied to Naumann: "The man himself is more interesting than his pictures" (Cross, II, 158). Eliot agreed with Lewes's observation in Life and Works of Goethethat German revivalist art had not only "a retrograde purpose which was bad" but also a "critical purpose which was good (II, 216). The critical purpose to which Lewes referred was the recovery of last traditions of Christian art, an educational endeavor which helped to overcome precisely the kind of ignorance displayed by George Eliot's description of Führich's Triumphzug According to Lewes, Overbeck and Cornelius '1ent real genius to the attempt to revive the dead forms of early Christian art" (II, 219). They did so not only in their own works but also by inspiring an important body of research into the history and iconography of European Pre-Raphaelite painting. Such studies were no doubt in Lewes's mind when he spoke in 1855 of "the services rendered by Romanticism in making the Middle Ages more thoroughly understood" (Life and Works of Goethe, II, 220). By Romanticism in this context, he and George Eliot meant a German, Catholic, neomedieval movement whose "main feature . . . was the exaltation of the Medieval above the Classic, of art animated by Christian spiritualism above the art animated by Greek humanism.''51

Largely published between 1835 and 1855, the scholarship inspired by Romanticism divided Dorothea's England of the first Reform Bill from George Eliot's of the second. Readers of Middlemarch are reminded that in Dorothea's day travelers to Rome

did not often carry full information on Christian art either in their heads or their pockets; and even the most brilliant English critic of the day mistook the flower-flushed tomb of the ascended Virgin for an ornamental vase due to the painter's fancy. Romanticism, which has helped to fill some dull blanks with love and knowledge, had not yet penetrated the times with its leaven and entered into everybody's food; it was fermenting still as a distinguishable vigorous enthusiasm in certain long-haired German artists at Rome.... [19:287]

Raphael, The Coronation of the Virgin. Vatican Museum. Figure 9 in print version. .

George Eliot's example of English ignorance is accurate and well-chosen.[84/85] In Notes of a Journey through France and Italy (1826), a book Dorothea might well have carried to Rome, William Hazlitt grossly misreads the iconography of Raphael's The Coronation of the Virgin in the Vatican Museum. Referring indeed to a "vase of flowers," Hazlitt fails to recognize the Marian resurrection symbolism of the lilies and roses that spring from the Virgin's sarcophagus. And he describes the twelve apostles as a "crowd" (p. 294). Readers of Middlemarch would almost certainly have possessed better "information on Christian art" than Hazlitt's. For example, Mrs. Jameson's popular Legends of the Madonna as Represented in the Fine Arts (1852) mentions five versions of the Coronation in which "the miraculous flowers" appear. Of Raphael's treatment Mrs. Jameson says: "Here we have the tomb below, filled with flowers; and around it the twelve apostles."54 For such gains in precision George Eliot thanked the "long-haired German artists" of the early nineteenth century.

In Middlemarch Naumann dramatizes the educational function of Romanticism when he plays the kindly didact to Dorothea. Her pre-Romantic ignorance of the conventions of Christian art prevents her from appreciating the "walls . . . covered with frescoes, or with rare pictures" that she sees in Rome (21:315). Although Dorothea's conscience is troubled by aesthetic apprehension per se, part of her difficulty is that often she simply does not know what the pictures represent. By explicating the iconography of his own neomedieval works, Naumann comes nearer than anyone else in the novel to teaching Dorothea how to look at traditional paintings which are not simple portraits or landscapes:

The painter in his confident English gave little dissertations on his finished and unfinished subjects . . . and Dorothea felt that she was getting quite new notions as to the significance of madonnas seated under inexplicable canopied thrones with the simple country as a background, and of saints with architectural models in their hands, or knives accidentally wedged in their skulls. Some things which had seemed monstrous to her were gathering intelligibility and even a natural meaning. [22:327-28]

Although the narrator's dry tone suggests considerable sympathy [85/86] with Dorothea's distaste for such subjects, the last sentence affirms a positive and welcome enlightenment. Here Naumann does in small what Romanticism will soon do for Europe at large: he gives "intelligibility and even a natural meaning" to symbols of Christian art that had come to seem unintelligible and unnatural.

Whether the conventions of medieval Christian art should determine the direction of nineteenth-century painting was, however, a different question in George Eliot's mind. On balance she felt they should not, because they distort more than they clarify. To teach Dorothea how to look at Madonnas is one thing; to paint her as one is another. Both Naumann and the narrator of Middlemarch present idealizing portraits of Dorothea as a Christian heroine, but the novel calls all such portraiture into doubt. One side of George Eliot's mind remained skeptical toward the pictorial idealization of character even as she was practicing it.

Ariadne. Vatican Museum. Figure 10 in print version.

When Naumann first encounters Dorothea in the Vatican Museum, her "Quakerish" costume and meditative expression inspire him to paint her as a personification of the Christian spirit, "dressed," since Naumann is Catholic, "as a nun" (19:289). Then he sees Dorothea as a "perfect young Madonna," and eventually he settles for painting her as Santa Clara (19:290, 22:331). But Dorothea's figure and attitude resemble those of the statue of Ariadne near which she stands, so there are pagan elements in the scene which prompt Naumann to a more comprehensive definition. He envisions Dorothea as "antique form animated by Christian sentiment — a sort of Christian Antigone — sensuous force controlled by spiritual passion" (19:290). This formulation unites the classical and the medieval, reconciling the great antitheses of German aesthetic debate in a higher synthesis.

Though suggestive, Naumann's exalted and schematic vision is only partly valid. Will Ladislaw immediately warns his friend not to confuse a symbolic conception of Dorothea with her human reality. Actually Naumann's allegorizing distorts his subjects, much as the fantasies of the male egoists in Adam Bede distort Hetty. Ladislaw alludes to Naumann's egoism when he accuses the painter of "looking at the world entirely from the studio point of view" (21:317), of thinking that art perfects life, and of believing that his picture of [86/87] Dorothea would be "the chief outcome of her existence — the divinity passing into higher completeness and all but exhausted in the act of covering [a] bit of canvas" (19:290). This is a critique of the solipsistic tendency inherent in Romantic aestheticism. It no doubt reflects the many charges of spiritual pride which Ruskin laid against the Nazarenes (see Modern Painters, V, 50, 54, 57, 89-90, 109, 323. George Eliot quoted the third of these passages in her review of Ruskin, "Art and Belles Lettres," Westminster Review, 65 (1856), 628. See also The Stones of Venice, Xl, 179, where Ruskin connects "the huge German cartoon" with human vanity.

This critique may also entail a more contemporary reference to the Victorian philosophy of art-for-art's-sake that had begun to spin off from Pre-Raphaelitism by the later 1860s. The critique also aligns Naumann with one of the grand themes of the novel: the inescapable corruption of aspiration by egoism. Compare, for example, Naumann's description of Dorothea with Walter Pater's description of Leonardo's Mona Lisa; in both, the lady's beauty is a synthesis of the major phases of western civilization, an incarnation of the collective wisdom and experience of her kind. Pater's essay on Leonardo was first published in 1869; in 1870 George Eliot dined at Oxford with "Mr. Pater, writer of articles on Leonardo da Vinci, Morris, etc." (Letters, V, 100).

Left: Sir Godfrey Kneller, John Locke Plate 12 in print version. Right: Palma Vecchio, Santa Barbara. Chiesa di Santa Maria Formosa, Venice. Figure 11 in print version.

Naumann's Christianizing aestheticism, then, is one of the many modes of human intellection tested and found wanting in Middlemarch Idealizing portraiture provides no coherent vision in this novel of incomplete insights. Ultimately Dorothea eludes all of the analogies that attempt to characterize her as Santa Clara, Santa Teresa, Santa Barbara, the Madonna, and a Christian Antigone, just as Mr. Casaubon more obviously eludes Naumann's vision of him as Saint Thomas Aquinas or Dorothea's comparison of him with "the portrait of Locke" (2:21). In The Art of George Eliot (1969), W. J. Harvey has argued that in Middlemarch such comparisons border upon the mock-heroic ( pp. 193-95; for a different interpretation of the mythological allusions in chapter 19 of Middlemarch, see Wiesenfarth, George Eliot's Mythmaking, pp. 194-97). George Eliot sometimes wished passionately to affirm the persistence of ideal types in everyday life (G. H. Lewes often called her "Madonna"), but at other times she was skeptical and satirical about just such affirmations; and her skepticism is by no means confined to Middlemarch. In Felix Holt, for example, she gently satirizes her own response to religious art in a scene between Felix and Esther Lyon: "He was looking up at her quite calmly, very much as a reverential Protestant might look at a picture of the Virgin, with a devoutness suggested by the type rather than by the image" (27:39).

Usually, of course, George Eliot tried to be as attentive to the image as to the type, and this attention often complicated her responses. She was, for instance, no indiscriminate admirer of Raphael's madonnas. Although she worshipped the Sistine Madonna, she disliked some of its earlier "sisters" for "their sheep-like look" (Cross, II, 189). In The Mill on the Floss she draws an unflattering analogy between these images and Mrs. Tulliver: "I have often [87/88] wondered whether those early Madonnas of Raphael, with the blond faces and somewhat stupid expression, kept their placidity undisturbed when their strong-limbed, strong-willed boys got a little too old to do without clothing" (I, 2:15).

Raphael, Saint Catherine of Alexandria. Figure 13 in print version.

Eliot's ambivalent vision sometimes issued in contradictory treatments of the same picture. Raphael's Saint Catherine, for example, was an early favorite of hers . At the age of twenty-five she told a friend that "you are a bright spot in my memory, like Raphael's Saint Catherine" (Letters, I, 188); and she may well have had the same painting in mind when Arthur Donnithorne refers to Dinah Morris as "St. Catherine in a Quaker dress" (5:91), and when one of the characters in Romola says that the heroine is "fit to be a model for a wise Saint Catherine of Egypt" (49:200; see Kingsley's use of this analogy). But Raphael's famous picture is treated much less reverently in Middlemarch when Dorothea, recuperating from her bereavement, begins to grow restless: "After three months Freshitt had become rather oppressive: to sit like a model for Saint Catherine looking rapturously at Celia's baby would not do for many hours in the day: (54:3-4). Viewed from this perspective, Raphael's saint seems posed and a bit silly.

George Eliot's ambivalence toward idealization also complicates her attitude toward sculpture. Her visit to Weimar in 1854 convinced her that she did not care for "classical idealising in portrait sculpture." She saw there several distasteful examples of the technique, including a "colossal statue of Goethe, executed after Bettina's design," which represents him "as a naked Apollo with a Psyche at his knee!" (Essays, p. 86). Any work in which the "artist tells us that the ideal of a Greek god divides his attention with his immediate subject" must be taken, Eliot warned, with a grain of salt. She declared herself particularly "irritated with idealization in portrait when, as in Dannecker's bust of Schiller, one has been misled into supposing that Schiller's brow was square and massive, while, in fact, it was receding" (Essays, p. 88). In other words, idealization must not exceed the bounds of phrenological realism. Yet in other moods Eliot was not at all averse to classical idealizing in portrait sculpture. She was particularly fond of heroic and monumental images of women, such as the cockle-woman she once saw at Swansea: "the grandest woman I ever saw — six feet high, carrying [88/89] herself like a Greek Warrior, and treading the earth with unconscious majesty" (Letters, II, 251). This taste for massive, Amazonian figures also manifests itself in Eliot's admiration of several pieces of contemporary sculpture: August Kiss's Mounted Amazon Attacked by a Tiger (Essays, p. 126) and Ludwig Schwanthaler's Bavaria (Cross, II, 21-22). Given her predilection for grand, statuesque female forms, she naturally visualized her own heroines as imposing creatures. Dorothea, for example, resembles the reclining Ariadne in the Vatican Museum, and the similarity is of amplitude as well as attitude. The full-grown Maggie Tulliver is a tall, queenly figure whose arm resembles either one of the Parthenon sculptures or a classical sculpture that George Eliot saw in Berlin. In "Janet's Repentance" we pause with the heroine's mother to admire Janet's "tall rich figure, looking all the grander for the plainness of the deep mourning dress, and the noble face with its massy folds of black hair, made matronly by a simple white cap. Janet had that enduring beauty which belongs to pure majestic outline and depth of tint" (4:195). In a word, Janet's beauty, like that of Isola Churchill, the heroine of G. H. Lewes's Ranthorpe, is "more sculpturesque than picturesque" (12). In Daniel Deronda the heroine is visualized in terms of Roman colored sculpture: "Dressed in black, without a single ornament, and with the warm whiteness of her skin set off between her light-brown coronet of hair and her square-cut bodice, she might have tempted an artist to try again the Roman trick of a statue in black, white, and tawny marble. Seeing her image slowly advancing, she thought, 'I am beautiful"' (23: 377). As usual, Gwendolen is the first to admire her own aesthetic effects.

Herein she differs from Mirah Cohen, who is all unconsciously transformed from "immovable, statue-like des" to "a coloured statue of serenity" (17:280, 52:159). On a smaller scale, Mirah is visualized as "an onyx cameo" (17:281), "a perfect cameo" (32: 144). As in the case of Mirah's suicidal despair, George Eliot often represents states of extreme emotional stress through an imagery of sculpture. See, for example, Adam Bede (27:10, 27:19, 43:223). Roman sculpture figures, too, in the presentation of Felix Holt: "Felix might have come from the hands of a sculptor in the later Roman period, when the plastic impulse was stirred by the grandeur of barbaric forms" (46:309). Although pagan sculptural idealization obviously does not involve the renewal of biblical types, it nevertheless serves much the same function as George Eliot's Christian pictorialism. Both modes of literary portraiture [89/90] hallow character by associating it with venerated traditional norms.

Eliot also elicited exemplary values from her literary portraits by grouping them in contrasting pairs. For example, the description just quoted of Felix Holt as a late-Roman statue occurs in combination with a description of Harold Transome as "a handsome portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence." The two Radicals, we are told, "certainly made a striking contrast" (46:309). A similar pairing takes place in Daniel Deronda: "Deronda, turning to look straight at Grandcourt who was on his left hand, might have made a subject for those old painters who liked contrasts of temperament" (15:240). Or again, in Adam Bede: "The family likeness between [Mrs. Poyser] and her niece Dinah Morris, with the contrast between her keenness and Dinah's seraphic gentleness of expression, might have served a painter as an excellent suggestion for a Martha and Mary" (6: 10',7).

In George Eliot's work such contrasts are usually moral as well as visual, and sometimes they border on the emblematic in their clear-cut, monitory juxtaposition of virtue and vice, altruism and egoism. In "Amos Barton," for example, Milly is compared in physiognomy and moral temperament with the Countess Czerlaski: "Look at the two women on the sofa together! The large, fair, mild-eyed Milly is timid even in friendship: it is not easy to her to speak of the affection of which her heart is full. The lithe, dark, thin-lipped countess is racking her small brain for caressing words and charming exaggerations" (3:48). Exemplary pairings of women may be found among George Eliot's earliest published writings (Essays, pp. 21-22), and as Constance Marie Fulmer points out in "Contrasting Pairs of Heroines in George Eliot's Fiction," they are an important device for unifying parallel plots in her mature fiction (Studies in the Novel, 6 (1974), 288-94).

Perhaps the best-known of Eliot's double portraits is the "Two Bed-Chambers" scene in chapter 15 of Adam Bede. Here Hetty Sorrel and Dinah Morris are contrasted in great visual and moral detail. Their surroundings, their appearances, and their physical and mental activities are set forth with a painstaking realism that emulates the spirit of Dutch painting. Yet these concrete descriptive details compose themselves into coherent symbolic patterns as well, so that Hetty's portrait incorporates many traditional symbols of vanity, whereas Dinah's abounds with familiar signs of contemplation [90/91] and spiritual rebirth. After describing the two women separately, George Eliot brings them together, as if joining two wings of a diptych.

What a strange contrast the two figures made! Visible enough in that mingled twilight and moonlight. Hetty, her cheeks flushed and her eyes glistening from her imaginary drama, her beautiful neck and arms bare, her hair hanging in a curly tangle down her back, and the baubles in her ears. Dinah, covered with her long white dress, her pale face full of subdued emotion, almost like a lovely corpse into which the soul has returned charged with sublimer secrets and a sublimer love. [15:238]

The uncharacteristic absence of predication in Eliot's syntax here reinforces the impression of static, juxtaposed icons. Although vanitas symbolism is common enough in seventeenth-century Dutch genre painting, this sort of stark moral contrast is not common.66 Eliot's description is so emblematic that one critic has actually proposed a direct iconographic parallel with Francis Quarles's emblem III, 14.67 This is not a convincing analogy, however. R. T. Jones is closer to the mark when he compares the scene to a hypothetical nineteenth-century painting: "It might be called 'Sacred and Profane Love,' and it might have been painted by, say, Holman Hunt" (George Eliot, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970, p. 17). This is a perceptive suggestion, especially if Jones is thinking of Hunt's famous pair of moral pictures , The Light of the World and The Awakening Conscience (see above).

Wilhelm von Schadow, Pietas und Vanitas: Parabel der klugen und törichten Jungfrauen. Figure 14 in print version.

Click upon thumbnail for larger image.

Yet Hunt never depicted two women together in quite the way that Eliot does here. A better pictorial analogy for "The Two Bed-Chambers" scene, if one need be sought, is Wilhelm von Schadow's Pietas und Vanitas: Parabel der klugen und törichten Jungfrauen (1842), a painting displayed at the great Munich exhibition of 1858 within two months of George Eliot's visit to the Bavarian capital.69 Schadow's wise and foolish virgins are juxtaposed as if in a diptych, equipped with contrasting symbolic accoutrements and differentiated by the directions of their gazes. Although the painting does not resemble George Eliot's text in every detail, the correspondences are nonetheless suggestive. A comparable Victorian painting, though done too late to have influenced Adam Bede, is Arthur D. Lemon's Pure Innocence and Pure in No Sense (ca. 1880); see Rodee, "Scenes of Rural and Urban Poverty," p. 141 and illus. 52.

This sort of contrast attains massive proportions in the structure [91/92] of Daniel Deronda, where the English and Jewish parts of the novel incorporate two distinctive and antithetical modes of literary portraiture. Both modes involve the idealization of character and the reincarnation of sacred types, but the novel treats one mode as false and the other as true. Throughout Deronda, George Eliot regularly visualizes Gwendolen and the other English characters in terms of the English portrait tradition, and especially of the "fancy" portraits that were fashionable among the upper classes in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Conversely, Eliot visualizes Daniel and other Jewish characters in terms of Italian Renaissance painting, especially that of Titian and the Venetian school. The contrasts between these two schools of painting reflect moral contrasts between the two races and cultures represented. George Eliot's characteristic ambivalence toward the pictorial idealization of character finds a complex resolution in the double plot of Daniel Deronda: her ironic portraiture has full play in the English half of the novel, while her ennobling portraiture finds a more ardent and affirmative expression in the Jewish part than anywhere else in her fiction.

Gwendolen, as we have seen, likes to imagine herself as the central subject of attractive pictures. Her favorite attitudes in these imaginary self-portraits are borrowed from the allegorical society portraiture of the Van Dyck tradition. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it was fashionable to idealize sitters by depicting them in costumes, poses, and settings that recall heroic, mythical, or religious figures from earlier works of art.71 Van Dyck popularized this technique of pictorial quotation in England when he transferred the baroque style of his Genoese religious work into his society portraiture. Thus he painted Lady Venetia Digby as Prudence, Rachel, Countess of Southampton, as Fortuna, and Mary, Duchess of Lenox, as Saint Agnes. Continuing the fashion,

Sir Peter Lely drew the Duchess of Cleveland as Juno, Mrs. Middleton as Pomona, Jane Kelleway as Diana, the Duchess of Rutland as Saint Agnes. Godfrey Kneller drew Anne, Lady Middleton, and Mrs. Voss and her daughter as Arcadian shepherdesses bearing staffs in their hands, and, on another occasion, the same Mrs. Voss as St. Agnes holding a prayer book in her hand and cuddling a lamb. [Hagstrum, Sister Arts, p. 146]

Reynolds, in his turn, portrayed Mrs. Quarrington as St. Agnes, [92/93] Mrs. Crewe as St Genevieve, The Daughters of Sir William Montgomery as the Graces Adorning a Term of Hymen, The Duchess of Manchester as Diana, Mrs. Blake as Juno, and the famous courtesan Kitty Fisher as Cleopatra.74 Because they allude to the subjects of historical or "fancy" painting, these pictures are often referred to as "fancy portraits" (Tinker, Painter and Poet, p. 14). That George Eliot was familiar with the term is shown by the fact that Latimer, the narrator of "The Lifted Veil," has been "the model of a dying minstrel in a fancy-picture" (1:295). It is with fancy portraits that Gwendolen is most prominently associated in Daniel Deronda. At the Archery Meeting in Brackenshaw Park, for example,

it was the fashion to dance in the archery dress, throwing off the jacket; and the simplicity of [Gwendolen's] white cashmere with its border of pale green set off her form to the utmost. A thin line of gold round her neck, and the gold star on her breast, were her only ornaments. Her smooth soft hair piled up into a grand crown made a clear line about her brow. Sir Joshua would have been glad to take her portrait. . . . [11:170]

Clearly Sir Joshua would have entitled the portrait Miss Harleth as Diana. Earlier in the same scene, a comparable portrait is evoked when we are told that "Gwendolen seemed a Calypso among her nymphs. It was in her attitudes and movements that every one was obliged to admit her surpassing charm" (10:147). We are dealing once more with Ovidian mythological fantasies of the sort that were treated so ironically in Adam Bede and Romola. The self-indulgence of the fantasies is underlined by the fact that Gwendolen is critical of other women who might figure in the same sort of painting. After observing that Charlotte Arrowpoint "would make quite a fine picture in that gold-coloured dress," Gwendolen decides that the picture would be "perhaps a little too symbolical — too much like the figure of Wealth in an allegory" (10:151). Too many allegorical figures might crowd Gwendolen's canvas.

Gwendolen's most memorable borrowed attitudes are Hermione and Saint Cecilia. The famous tableau of Hermione in Daniel Deronda is indebted to a similar scene in Goethe's Die Wahlverwandtschaften, which was in turn inspired by the drawing-room attitudes of Lady Emma Hamilton. In her tableau Gwendolen chooses to imitate the attitude in which Mrs. Siddons and other [93/94] eighteenth-century actresses regularly played the statue scene in The Winter's Tale: "Hermione, her arm resting on a pillar, was elevated by about six inches, which she counted on as a means of showing her pretty foot and instep, when at the given signal she should advance and descend" (6:85).

Left: Adam Buck, Mrs. Siddons as Hermione. Right: Johann Zoffany, Miss Farren in "The Winter's Tale." Figures 15 and 16 in print version.

Edgar Wind, in his classic essay on English heroic portraiture in the eighteenth century, reproduces engravings of Mrs. Siddons and Miss Farren in the role of Hermione, holding precisely this pose. He shows that the attitude descends from classical representations of the Muses, and that it was "an established formula" for all actresses who played the statue scene in the eighteenth century.77 Gwendolen, then, is imitating pictures of Mrs. Siddons as Hermione. As Wind notes, in society masquerades the ladies "often learned the attitudes which they assumed from actresses on the stage" ("Humanitatsidee," pp. 222, 224). Wind reproduces a drawing of Mrs. Siddons as Hermione from the sketchbook of a young lady, Mary Hamilton, who depicted the attitudes and costumes of Mrs. Siddons in a variety of roles, with a view to recreating them in private entertainments.

Gwendolen's Hermione is designed primarily to allow her to display "a statuesque pose" in her Greek dress (6:82). The planned effect perfectly exemplifies Ruskin's assertion in Modern Painters, vol. III that "the modern 'ideal' of high art is a curious mingling of the gracefulness and reserve of the drawing-room with a certain measure of classical sensuality" (V, 96). But it is Gwendolen's expression, not her attitude, that is affected by the sudden apparition of the prophetic picture of the dead face and fleeing figure. Instead of assuming the radiant face of comedy appropriate to the end of The Winter's Tale, Gwendolen unwittingly dons the mask of tragedy:

Gwendolen . . . stood without change of attitude, but with a change of expression that was terrifying in its terror. She looked like a statue into which a soul of Fear had entered: her pallid lips were parted; her eyes, usually narrowed under their long lashes, were dilated and fixed. [6:86]

The complacent beauty has now become a study in physiognomical expression, a sculpturesque representation of Terror, one of the two passions appropriate to Aristotelian tragedy. Instead of Miss Harleth as Hermione, we have, still in the Reynolds tradition, Miss Harleth as the Tragic Muse. The picture distinctly recalls Piero di Cosimo's picture of Tito as a terror-stricken reveller in Romola.

More to Gwendolen's taste is the attitude of Saint Cecilia:

"Here is an organ. I will be Saint Cecilia: some one shall paint me as Saint Cecilia. Jocosa (this was her name for Miss Merry), let down my hair. See, mamma!"

She had thrown off her hat and gloves, and seated herself before the organ in an admirable pose, looking upward; while the submissive and sad Jocosa took out the one comb which fastened the coil of hair, and then shook out the mass till it fell in a smooth light-brown stream far below its owner's slim waist. Mrs Davilow smiled and said, "A charming picture, my dear!" not indifferent to the display of her pet, even in the presence of a housekeeper. Gwendolen rose and laughed with delight. All this seemed quite to the purpose on entering a new house which was so excellent a background. [3:33-34]

Left: Sir Godfrey Kneller, Lady Elizabeth Cromwell as Saint Cecilia. Right: Sir Joshua Reynolds, Mrs. Sheridan s Saint Cecilia. Figures 17 ad 18 in print version.

Here the imaginary portrait is in the style of Kneller's Lady Elizabeth Cromwell as Saint Cecilia (1703), Reynolds's Mrs. Sheridan as Saint Cecilia (1775), or Reynolds's Mrs Billington as Saint Cecilia (1790; shown at the National Portrait Exhibition of 1867; see Waterhouse, De Rothschild Collection, pp. 86-89). The aristocratic life to which Gwendolen aspires is again presented as an eighteenth-century affair. The attitude of Saint Cecilia in society portraiture was familiar enough by 1735 to be an object of Pope's satire in Moral Essay II, "On the Characters of Women":

How many pictures of one Nymph we view,

All how unlike each other, all how true!

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Let then the Fair one beautifully cry,

In Magdalen's loose hair and lifted eye,

Or drest in smiles of sweet Cecilia shine,

With simp'ring Angels, Palms, and Harps divine;

Whether the Charmer sinner it or saint it,

If folly grows romantic, I must paint it.81

Hagstrum's The Sister Arts cites this passage after listing the representations of Saint Cecilia best known in the seventeenth century (pp. 204-06). Fancy portraits were also satirized by Oliver Goldsmith in chapter 16 of The Vicar of Wakefield. Edgar Wind argues that English allegorical portraiture reflects a heroic conception of mankind, and other scholars have defended them. But Pope and George Eliot see in such portraiture mainly the affectation and folly of the social class [95/96] depicted. Indeed, for the middle-class Victorian intellectual, fancy portraits must have epitomized all that was Dandy about the fashionable classes under George III and George IV. Ruskin strikes the characteristic Victorian tone in the third volume of Modern Painters when he speaks of paintings which

introduce pretty children as cherubs, and handsome women as Magdalens and Maries of Egypt, or portraits of patrons in the character of the more decorous saints; but more frequently, for direct flatteries of this kind, recurring to pagan mythology, and painting frail ladies as goddesses or graces, and foolish kings in radiant apotheosis. [V, 93-94]

The portraits in which Gwendolen loves to see herself do not in George Eliot's view truly idealize their subjects; they falsify in order to please the vanity of their subjects. Hans Meyrick temporarily resists Sir Hugo Mallinger's advice to take up portraiture because the sort of painter Sir Hugo has in mind "has a little truth, and a great facility in falsehood — [his] idealism will never do for gods and goddesses and heroic story, but it may fetch a high price as flattery" (52:152). That Hans has higher standards of truthfulness in portraiture is perhaps suggested by the fact that he is "christened after Holbein" and that "only to look at his pinched features and blond hair dangling over his collar reminded one of pale quaint heads by early German painters" (16:270).

Left: Rembrandt, Bust of a Bearded Man in a Cap. Purchased as Jewish Rabbi. Figure 19 in print version. Click upon thumbnail for larger image.

Early German is not the only school to be contrasted with the English in Daniel Deronda Before discussing George Eliot's Italian sources, we should glance briefly at her use of the Dutch school in the presentation of Mordecai. Eliot's idealization of Mordecai is pictorial and overtly typological. Daniel's first impression of the consumptive scholar is that "such a physiognomy as that might possibly have been seen in a prophet of the Exile, or in some New Hebrew poet of the medieval time" (33:165). Later Daniel sees Mordecai as "an illuminated type of bodily emaciation and spiritual eagerness" (40:327). For Hebrew portraiture Eliot turned naturally to Rembrandt's pictures of rabbis. G. H. Lewes spoke of "a Rembrandtish background to her dramatic presentation" of the Jews in Daniel Deronda (Letters, Vl, 196), and certainly a Rembrandtish chiaroscuro is suggested by the first glimpse of Mordecai's face, [96/97] "with its dark, far-off gaze, and yellow pallor in relief on the gloom of the backward shop" (33:165; see Davis, "Pictorialism in George Eliot's Art," pp. 210-37). Later Hans Meyrick, who is painting the picturesque figure, says: "Our prophet is an uncommonly interesting sitter — a better model than Rembrandt had for his Rabbi" (52:147). It is difficult to know which of Rembrandt's so-called rabbis Hans has in mind, but perhaps he is referring to the only one in the collection of the National Gallery, purchased under the title A Jewish Rabbi in 1844. The picturesque caps of Rembrandt's sitters were probably in George Eliot's memory when she wrote of Mordecai: "he commonly wore a cloth cap with black fur round it, which no painter would have asked him to take off" (38: 298). Mordecai himself may be thinking of Rembrandt when he envisions his messiah "from his memory of faces seen among the Jews of Holland and Bohemia, and from the pictures which revived that memory" (38:300).

Nevertheless, Dutch art does not dominate the Jewish part of Daniel Deronda as completely as might be expected. It is an exaggeration to say, as Harold Fisch does in "Daniel Deronda, or Gwendolen Harleth?", that "the Jewish portraiture of Rembrandt" is "the true prototype" of George Eliot's treatment of the Jews (Nineteenth-Century Fiction, 19 (1965), 354-55). Except for Mordecai, no important character in the novel is associated with Rembrandt's portraiture. Eliot's use of Dutch painting is highly selective, no doubt because the idealization she wished to confer upon her Jewish characters was incompatible with her audience's preconceptions about the limitations of the Dutch school. No one did more than Eliot herself had done in Adam Bede to foster the notion that the province of Dutch art is "the faithful rendering of commonplace things," and that it depicts "few prophets . . . few sublimely beautiful women; few heroes" (17:270). In Adam Bede Dutch models sufficed for the mundane range of experience she wised to present. But in Daniel Deronda she ventures into precisely those extraordinary reaches of experience which she chose to avoid in Adam Bede. She could not make an extensive use of Dutch models because she shared with a substantial part of her audience the venerable prejudice that Dutch painting rarely achieves the sublime.86

Instead she relies heavily upon Italian, especially Venetian, models. So persistently does she associate Jews with Italians that the Anglo-Saxon [97/98] reader of Daniel Deronda is induced almost subliminally to grant the Jews whatever tolerance and respect he is accustomed to grant the Italians. It is as though George Eliot were saying to her Protestant English audience: you have learned to appreciate the Italians despite their ethnic, religious, and cultural foreignness; you can learn to appreciate the Jews in the same way: both peoples are of Mediterranean origin, both have distinguished non-Protestant religious traditions, and the Italian Renaissance painting you admire realizes many motifs of the Hebrew scriptures. (Disraeli's hero in Lothair (1870) makes a similar point when discussing the influence of "Semitism" upon "Aryan art" [chap. 29].) Eliot's pictorialism, in other words, here becomes a sophisticated rhetorical device employed in the service of a liberal social vision.

The Italian connection affects major and minor characters alike. An elderly man at the synagogue in Frankfurt, for example, has an "ample white beard and felt hat framing a profile of that fine contour which may as easily be Italian as Hebrew" (32:136). Of Klesmer, the Jewish pianist, the narrator says: "draped in a loose garment with a Florentine berretta on his head, he would have been fit to stand by the side of Leonardo da Vinci" (10:149).88 Even Mirah Cohen is associated with Italians in Hans Meyrick's Titus and Berenice series; she is to be the model for the Jewish mistress of the prospective emperor of Rome. The series was originally suggested, as Hans explains, by "a splendid woman in the Trastevere — the grandest women there are half Jewesses — and she set me hunting for a fine situation of a Jewess at Rome" (37:276). The fusion of Jewish and Roman identities here is threefold: in Berenice, in the Trasteverina, and by association in Mirah.89

Finally, Daniel Deronda himself, who learns in Genoa that he is a Jew, has "a face not more distinctively oriental than many a type seen among what we call the Latin races" (40:332). Gwendolen's mother says the same thing more concisely: "he puts me in mind of Italian paintings" (29: 83). That Deronda does not belong pictorially to the English school is made clear when Gwendolen notices that "hardly any face could be less like Deronda's than that represented as Sir Hugo's in a crayon portrait at Diplow" (29:84).

Of the regional schools of Italian painting evoked in Daniel Deronda, the most prominent is the Venetian. Venetian painting regained its prestige in England in the 1860s and 1870s after the rage [98/99] for Pre-Raphaelite styles had run its course. Ruskin's revaluation of the Venetian school in the last volume of Modern Painters (1860) concludes that "the Venetian mind . . . and Titian's especially, as the central type of it, was wholly realist, universal, and manly.... In all its roots of power, and modes of work . . . I find the Venetian mind perfect" (VII, 296-98.). Earlier in the same work Ruskin contrasted Venetian Renaissance portraiture to modern English portraiture in terms that parallel George Eliot's handling of the two schools in Daniel Deronda:

the first step towards the ennobling of any face is the ridding it of its vanity; to which aim there cannot be anything more contrary than that principle of portraiture which prevails with us in these days, whose end seems to be the expression of vanity throughout, in face and in all circumstances of accompaniment; tending constantly to insolence of attitude, and levity and haughtiness of expression, and worked out farther in mean accompaniments of worldly splendour and possession . . . whence has arisen such a school of portraiture as must make the people of the nineteenth century the shame of their descendants, and the butt of all time. To which practices are to be opposed both the glorious severity of Holbein, and the mighty and simple modesty of Raffaelle, Titian, Giorgione, and Tintoret, with whom armour does not constitute the warrior, neither silk the dame. And from what feeling the dignity of that portraiture arose is best traceable at Venice. [IV 193. See also "Sir Joshua and Holbein," XIX, 5-12]

According to Ruskin, painting done before 1600 embodies a greater purity of religious spirit than painting done since, and the Venetians "were the last believing school of Italy" (VII, 286). Hence the Venetian school is appropriate to the Jewish characters in Daniel Deronda, who have preserved a vital contact with their ancient religion; whereas the modern school is appropriate to the English characters, who are vain and worldly. In characterizing modern portraiture as an art of vanity, Ruskin anticipates George Eliot's pictures of Gwendolen.

Among the Victorians the chief technical excellence of the Venetian painters was generally held to be their color. In The Stones of Venice [100/101] Ruskin spoke of "that mighty spirit of Venetian colour, which was to be consummated in Titian," and argued that there is always a "connexion of pure colour with profound and noble thought" (X, 64, 174. See also John Gage, Colour in Turner: Poetry and Truth (London: Studio Vista 1969), p. 91). In Deronda George Eliot draws upon the pure color values of Venetian painting when she describes Daniel's visit to the family of Ezra Cohen:

When she showed him into the room behind the shop he was surprised at the prettiness of the scene.... The ceiling and walls were smoky, and all the surroundings were dark enough to throw into relief the human figures, which had a Venetian glow of colouring. The grandmother was arrayed in yellowish brown with a large gold chain in lieu of the necklace, and by this light her yellow face with its darkly-marked eyebrows and framing roll of grey hair looked as handsome as was necessary for picturesque effect. Young Mrs Cohen was clad in red and black, with a string of large artificial pearls wound round and round her neck: the baby lay asleep in the cradle under a scarlet counterpane; Adelaide Rebekah was in braided amber; and Jacob Alexander was in black velveteen with scarlet stockings. As the four pairs of black eyes all glistened a welcome at Deronda, he was almost ashamed of the supercilious dislike these happy-looking creatures had raised in him by daylight. [34:178-79]

Here the Venetian aura of color in the group portrait dignifies the London Jewish family in Deronda's eyes and is meant to have the same effect upon the reader. Structurally, the scene is a conversation piece (see chap. 7). It may recall Simeon Solomon's "Illustrations of Jewish Customs," The Leisure Hour, vol 15 (1866). Once again we see "Hebrew dyed Italian" (55:213). No doubt the coloristic style of Venetian painting seemed to George Eliot more exotic, more "oriental," and therefore more appropriate to her Jewish characters than did the linear styles of other Italian schools.

The Annunciation by Titian (Tiziano Vecellio, 1488/1490-1576). 1535. Oil on canvas, 166 � 266. Collection: Scuola di San Rocco, Venice.

If Reynolds dominates the English portraiture in Daniel Deronda, then Titian dominates the Jewish. "One can," says Jean Hagstrum, "almost always count on a literary Englishman's admiration of Titian" (SisterArts, p. 164). In a sense, the entire novel was inspired by a Titian painting — the Annunciation at the Scuola di San Rocco in Venice, which gave George Eliot the theme she developed first in The Spanish Gypsy and later in Deronda. In "this small picture of [100/101] Titian's," she found "a great dramatic motive": a young person

chosen to fulfil a great destiny . . . chosen, not by any momentary arbitrariness, but as a result of foregoing hereditary conditions . . . I came home with this in my mind, meaning to give the motive a clothing in some suitable set of historical and local conditions. [Cross, III, 34-35]

Here is an excellent example of the typological thinking that underlies so much of Eliot's art. Titian's handling of a traditional biblical type inspires Eliot to reincarnate the same type in a more contemporary setting.

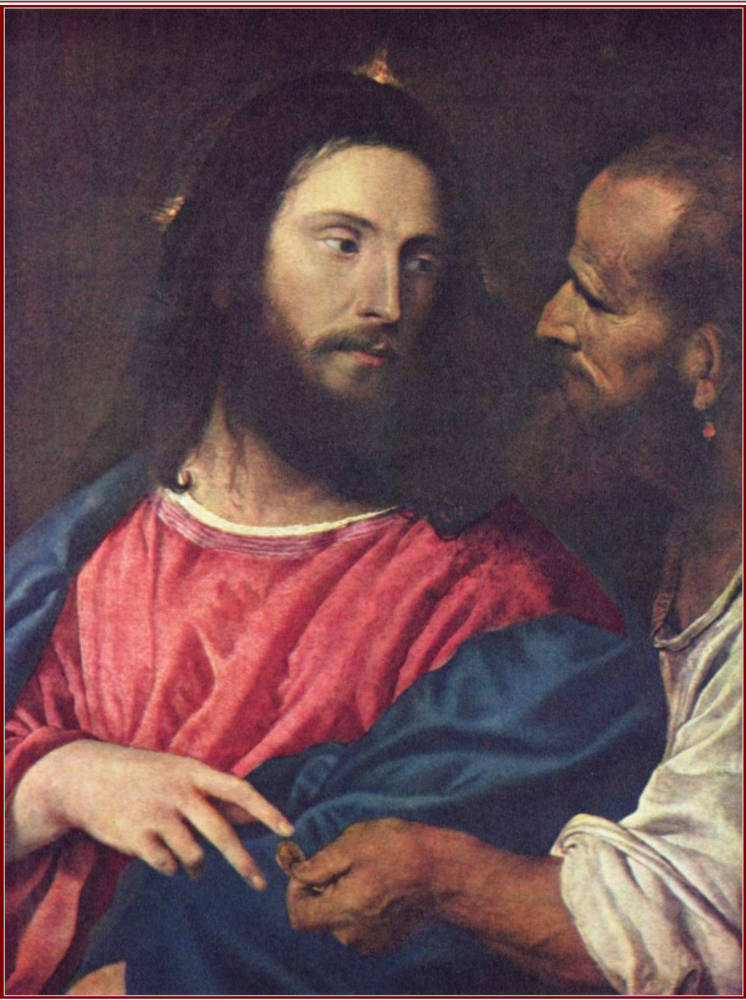

Left: Titian, The Young Man with a Glove. Right: Titian, The Tribute Money Figures 21 and 22 in print version.

Small wonder, then, that the literary portraiture of George Eliot's hero derives principally from two of Titian's paintings. In the early part of the novel, before he has accepted his Zionist mission, Daniel is associated with a secular portrait in the Louvre — The Young Man with a Glove. In the later part of the novel, after his destiny has been revealed, Daniel is associated with a religious painting at Dresden — The Tribute Money. The change of portraits symbolizes Daniel's progression from a life of aimless upper-class ease to a life of religious commitment. Deronda comes to exemplify G. H. Lewes's belief that "a well-painted face, with a noble expression, is the highest reach of art" ("Realism in Art," p. 499). Earlier in the novel the Meyrick girls create their own portrait of "Deronda as an ideal" when they set about "to paint him as Prince Camaralzaman," hero of one of the Arabian Nights (16:275).

The Young Man with a Glove is evoked in chapter 17 as Deronda rows on the Thames:

Look at his hands: they are not small and dimpled, with tapering fingers that seem to have only a deprecating touch: they are long, flexible, firmly-grasping hands, such as Titian has painted in a picture where he wished to show the combination of refinement with force. And there is something of a likeness, too, between the faces belonging to the hands — in both the uniform pale-brown skin, the perpendicular brow, the calmly-penetrating eyes. [17:277-78]

George Eliot might have seen this portrait during visits to the Louvre in 1859 and again in 1864 (Cross, II, 96 and "Italy 1864," Beinecke Library, entry 6 May). Here is Deronda as handsome young gentleman, idle perhaps but potentially energetic and less affected than he might be if he belonged to the English school. The young man's potential is fully realized in the painting that represents Deronda's later, more spiritual aspect. Titian's [102/103] The Tribute Money is evoked immediately after Deronda is recognized by Mordecai as the incarnation of his messianic vision:

In ten minutes the two men, with as intense a consciousness as if they had been two undeclared lovers, felt themselves alone in the small gas-lit book-shop and turned face to face, each baring his head from an instinctive feeling that they wished to see each other fully. . . . I wish I could perpetuate those two faces, as Titian's "Tribute Money" has perpetuated another type of contrast. Imagine — we all of us can — the pathetic stamp of consumption with its brilliancy of glance to which the sharply-defined structure of features reminding one of a forsaken temple, give already a far-off look as of one getting unwillingly out of reach; and imagine it on a Jewish face naturally accentuated for the expression of an eager mind-the face of a man little above thirty, but with that age upon it which belongs to time lengthened by suffering, the hair and beard still black throwing out the yellow pallor of the skin, the difficult breathing giving more decided marking to the mobile nostril, the wasted yellow hands conspicuous on the folded arms. . . . Seeing such a portrait you would see Mordecai. And opposite to him was a face not more oriental than many a type seen among what we call the Latin races: rich in youthful health, and with a forcible masculine gravity in its repose, that gave the value of judgment to the reverence with which he met the gaze of this mysterious son of poverty who claimed him as a long-expected friend. [40: 33 1-32]

The scene in the bookshop is analogous, not identical, to the scene in The Tribute Money. In particular, Mordecai does not resemble the tax-collecting Pharisee through whom Jesus renders unto Caesar what is Caesar's. Yet Titian's Christ looks enough like The Young Man with a Glove to resemble Deronda as well, and Deronda is bearded. Probably we are meant to visualize Deronda in terms of Titian's Christ (see Laski, p. 84). "In this way," to borrow a remark made by Albert R. Cirillo in another context, "Eliot fleshes out Daniel's portrait as a paragon, as a symbol, or personal savior."99 That Daniel's Portrait involves a form of typological incarnation [103/104] is strongly suggested by the language of the novel. Deronda is "the antitype of [the] visionary image in Mordecai's mind" (41:352). An antitype is not the opposite of a type but its fulfillment. As soon as he meets Daniel, Mordecai is struck by "a face and frame which seemed to him to realise the long-conceived type . . . Deronda had that sort of resemblance to the preconceived type which a finely individual bust or portrait has to the more generalised copy left in our minds after a long interval" (38:307-08). The type in question reveals its virtues through its expression; it has "a face at once young, grand, and beautiful, where, if there is any melancholy, it is no feeble passivity, but enters into the foreshadowed capability of heroism" (38:298). This face, at once contemplative and active, belongs both to Mordecai's messiah and to Titian's Christ in The Tribute Money. In effect, Eliot seeks to make Deronda a convincing postfiguration of Christ in her secular religion of humanity by contrasting his unconscious pictorial fulfillment of the role with Gwendolen's self-conscious fulfillment of the pictorial roles of saints and goddesses in fashionable society portraiture.