ord Methuen’s force had now fought three actions m the space of a single week, losing in killed and wounded about a thousand men, or rather more than one-tenth of its total numbers. Had there been evidence that the enemy were seriously demoralised, the General would no doubt have pushed on at once to Kimberley, which was some twenty miles distant. The information which reached him was, however, that the Boers had fallen back upon the very strong position of Spytfontein, that they were full of fight, and that they had been strongly reinforced by a commando from Mafeking. Under these circumstances Lord Methuen had no choice but to give his men a well-earned rest, and to await reinforcements. There was no use in reaching Kimberley unless he had completely defeated the investing force. With the history of the fh-st relief of Lucknow in his memory he was on his guard against a repetition of such an experience.

It was the more necessary that Methuen should strengthen his position, since with every mile which he advanced the more exposed did his line of communications become to a raid from Fauresmith and the southern districts of the Orange Free State. Any serious danger to the railway behind them would leave the British Army in a very critical position, and precautions were taken [150/151] for the protection of the more vulnerable portions of the line. It was well that this was so, for on the 8th of December Commandant Prinsloo, of the Orange Free State, with a thousand horsemen and two light seven-pounder guns, appeared suddenly at Enslin and vigorously attacked the two companies of the Northampton Regiment who held the station. At the same time they destroyed a couple of culverts and tore up three hundred yards of the permanent way. For some hours the Northamptons under Captain Godley were closely pressed, but a telegram had been despatched to Modder Camp, and the 12th Lancers with the ubiquitous 62nd Battery were sent to their assistance. The Boers retired with their usual mobility, and in ten hours the line was completely restored .

Reinforcements were now reaching the Modder River force, which made it more formidable than when it had started. A very essential addition was that of the 12th Lancers and of G battery of Horse Artillery, which would increase the mobility of the force and make it possible for the General to follow up a blow after he had struck it. The magnificent regiments which formed the Highland Brigade — the 2nd Black Watch, the 1st Gordons, the 2nd Seaforths, and the 1st Highland Light Infantry — had arrived under the gallant and ill-fated Wauchope. Four five-inch howitzers had also come to strengthen the artillery. At the same time the Canadians, the Australians, and several line regiments were moved up on the line from De Aar to Belmont. It appeared to the public at home that there was the material for an overwhelming advance; but the ordinary observer, and even perhaps the military critic, had not yet appreciated how great is the advantage which is given by modern weapons to the force which acts upon the defensive. [151/152] With enormous pains the dark Cronje and his men were entrenching a most formidable position in front of our advance, with a confidence, which proved to be justified, that it would be on their own ground and under their own conditions that in this, as in the three preceding actions, we should engage them.

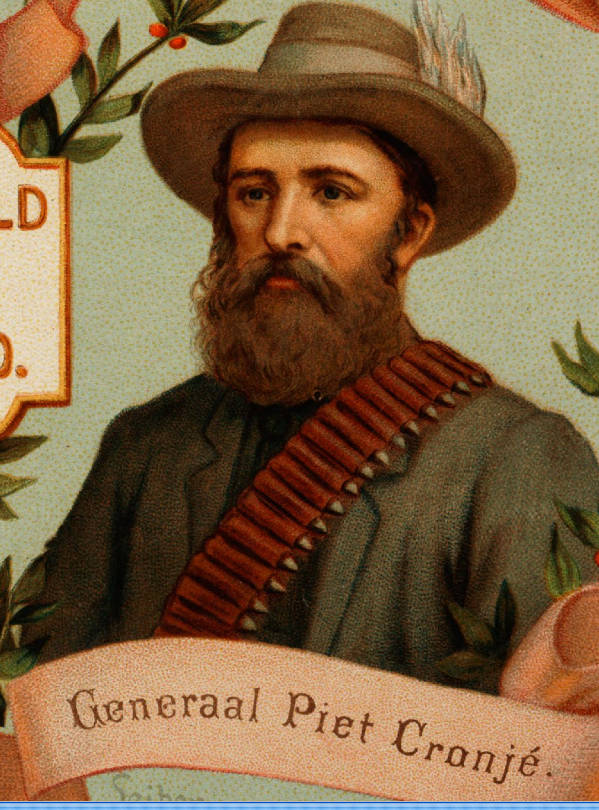

General Piet Cronje. from F. Lieber’s nine portraits of Boer generals and officers. Click on image to enlarge it.

On the morning of Saturday, December 9th, the British General made an attempt to find out what lay in front of him amid that semicircle of forbidding hills. To this end he sent out a reconnaissance in the early morning, which included G Battery Horse Artillery, the 9th Lancers, and the ponderous 4.7 naval gun, which, preceded by the majestic march of thirty-two bullocks and attended by eighty seamen gunners, creaked forwards over the plain. What was there to shoot at in those sunlit boulder-strewn hills in front? They lay silent and untenanted in the glare of the African day. In vain the great gun exploded its huge shell with its fifty pounds of lyddite over the ridges, in vain the smaller pieces searched every cleft and hollow with their shrapnel. No answer came from the far-stretching hills. Not a flash or twinkle betrayed the fierce bands who lurked among the boulders. The force returned to camp no wiser than when it left.

There was one sight visible every night to all men which might well nerve the rescuers in their enterprise. Over the northern horizon, behind those hills of danger, there quivered up in the darkness one long, flashing, quivering beam, which swung up and down, and up again like a seraphic sword-blade. It waas Kimberley praying for help, Kimberley solicitous for news, Anxiously, distractedly, the great De Beers searchlight dipped and rose. And back across the twenty miles of darkness, over the hills where the dark Cronje lurked, [152/153] there came that other southern column of light which answered, and promised, and soothed. ‘Be of good heart, Kimberley. We are here! The Empire is behind us. We have not forgotten you. It may be days, or it may be weeks, but rest assured that we are coming.’

About three in the afternoon of Sunday, December 10, the force which was intended to clear a path for the army through the lines of Magersfontein moved out upon what proved to be its desperate enterprise. The 3rd or Highland Brigade included the Black Watch, the Seaforths, the Argyll and Sutherlands, and the Highland Light Infantry. The Gordons had only arrived in camp that day, and did not advance until next morning. Besides the infantry, the 9th Lancers, the mounted infantry, and all the artillery moved to the front. It was raining hard, and the men with one blanket between two soldiers bivouacked upon the cold damp ground, about three miles from the enemy’s position. At one o'clock, without food, and drenched, they moved forwards through the drizzle and the darkness to attack those terrible lines.

Clouds drifted low in the heavens, and the falling rain made the darkness more impenetrable. The Highland Brigade was formed into a column — the Black Watch in front, then the Seaforths, and the other two behind. To prevent the men from straggling in the night the four regiments were packed into a mass of quarter column as densely as was possible, and the left guides held a rope in order to preserve the formation. With many a trip and stumble the ill-fated detachment wandered on, uncertain where they were going and what it was that they were meant to do. Not only among the rank and file, but among the principal [153/154] officers also, there was the same absolute ignorance. Brigadier Wauchope knew, no doubt, but his voice was soon to be stilled in death. The others were aware, of course, that they were advancing either to turn the enemy’s trenches or to attack them, but they may well have argued from their own formation that they could not be near the riflemen yet. Why they should be still advancing in that dense clump we do not now know, nor can we surmise what thoughts were passing through the mind of the gallant and experienced chieftain who walked beside them. There are some who claim on the night before to have seen upon his strangely ascetic face that shadow of doom which is summed up in the one word ‘fey.’ The hand of coming death may already have lain cold upon his soul. Out there, close beside him, stretched the long trench, fringed with its line of fierce, staring, eager faces, and its bristle of gun-barrels. They knew he was coming. They were ready. They were waiting. But still, with the dull murmur of many feet, the dense column, nearly four thousand strong, wandered onwards through the rain and the darkness, death and mutilation crouching upon their path. It matters not what gave the signal, whether it was the flashing of a lantern by a Boer scout, or the tripping of a soldier over wire, or the firing of a gun in the ranks. It may have been any, or it may have been none, of these things. As a matter of fact I have been assured by a Boer who was present that it was the sound of the tins attached to the alarm wires which disturbed them. However this may be, in an instant there crashed out of the darkness into their faces and ears a roar of point-blank fire, and the night was slashed across with the throbbing flame of the rifles. At the moment [154/155] before this outflame some doubt as to their whereabouts seems to have flashed across the mind of their leaders. The order to extend had just been given, but the men had not had time to act upon it. The storm of lead burst upon the head and right flank of the column, which broke to pieces under the murderous volley. Wauchope was shot, struggled up, and fell once more for ever. Rumour has placed words of reproach upon his dying lips, but his nature, both gentle and soldierly, forbids the supposition. ‘What a pity!’ was the only utterance which a brother Highlander ascribes to him. Men went down in swathes, and a howl of rage and agony, heard afar over the veldt, swelled up from the frantic and struggling crowd. By the hundred they dropped — some dead, some wounded, some knocked down by the rush and sway of the broken ranks. It was a horrible business. At such a range and in such a formation a single Mauser bullet may well pass through many men. A few dashed forwards, and were found dead at the very edges of the trench. The head of the brigade broke and, disentangling themselves with difficulty from the dead and the dying, fled back out of that accursed place. Some, the most unfortunate of all, became caught in the darkness in the wire defences, and were found in the morning hung up like ‘crows,’ as one spectator describes it, and riddled with bullets.

Who shall blame the Highlanders for retiring when they did? Viewed, not by desperate and surprised men, but in all calmness and sanity, it may well seem to have been the very best thing which they could do. Dashed into chaos, separated from their ofiicers, with no one who knew what was to be done, the first necessity was to gain shelter from this deadly fire, which had already stretched six hundred of their number upon the [155/156] ground. The danger was that men so shaken would be stricken with panic, scatter in the darkness over the face of the country, and cease to exist as a military unit. But the Highlanders were true to their character and their traditions. There was shouting in the darkness, hoarse voices calling for the Seaforths, for the Argylls, for Company C, for Company H, and everywhere in the gloom there came the answer of the clansmen. Within half an hour with the break of day the Highland regiments had re-formed (a company and a half left of the Black Watch), and, shattered and weakened, but undaunted, prepared to renew the contest. Some attempt at an advance was made upon the right, ebbing and flowing, one little band even reaching the trenches and coming back with prisoners and reddened bayonets. For the most part the men lay upon their faces, and fired when they could at the enemy; but the cover which the latter kept was so excellent that an officer who expended 120 rounds has left it upon record that he never once had seen anything positive at which to aim. Lieutenant Lindsay brought the Seaforths’ Maxim into the firing-line, and, though all her crew except two were hit, it continued to do good service during the day. The Lancers' Maxim was equally staunch, though it also was left finally with only the lieutenant in charge and one trooper to work it.

Fortunately the guns were at hand, and, as usual, they were quick to come to the aid of the distressed. The sun was hardly up before the howitzers were throwing lyddite at 4,000 yards, the three field batteries (18th, 62nd, 75th) were working with shrapnel at a mile, and the troop of Horse Artillery was up at the right front trying to enfilade the trenches. The guns kept down the rifle-fire, and gave the wearied Highlanders some [156/157] respite from their troubles. The whole situation had resolved itself now into another Battle of Modder River. The infantry, under a fire at from six hundred to eight hundred paces, could not advance and would not retire. The artillery only kept the battle going, and the huge naval gun from behind was joining with its deep bark in the deafening uproar. But the Boers had already learned — and it is one of their most valuable military qualities that they assimilate their experience so quickly — that shell fire is less dangerous in a trench than among rocks. These trenches, very elaborate in character, had been dug some hundreds of yards from the foot of the hills, so that there was hardly any guide to our artillery fire. Yet it is to the artillery fire that all the losses of the Boers that day were due. The cleverness of Cronje’s disposition of his trenches some hundred yards ahead of the kopjes is accentuated by the fascination which any rising object has for a gunner. Prince Kraft tells the story of how at Sadowa he unlimbered his guns two hundred yards in front of the church of Chlum, and how the Austrian reply fire almost invariably pitched upon the steeple. So our own gunners, even at a two-thousand yard mark, found it difficult to avoid overshooting the invisible line, and hitting the obvious mark behind.

As the day wore on reinforcements of infantry came up from the force which had been left to guard the camp. The Gordons arrived with the first and second battalions of the Coldstream Guards, and all the artillery was moved nearer to the enemy’s position. At the same time, as there were some indications of an attack upon our right flank, the Grenadier Guards with five companies of the Yorkshire Light Infantry were moved up in that direction, while the three remaining companies of Barter’s [167/168] Yorkshiremen secured a drift over which the enemy might cross the Modder. This threatening movement upon our right flank, which would have put the Highlanders into an impossible position had it succeeded, was most gallantly held back all morning, before the arrival of the Guards and the Yorkshires, by the mounted infantry and the 12th Lancers, skirmishing on foot. It was in this long and successful struggle to cover the flank of the 3rd Brigade that Major Milton, Major Ray, and many another brave man met his end. The Coldstreams and Grenadiers relieved the pressure upon this side, and the Lancers retired to their horses, having shown, not for the first time, that the cavalryman with a modern carbine can at a pinch very quickly turn himself into a useful infantry soldier. Lord Airlie deserves all praise for his unconventional use of his men, and for the gallantry with which he threw both himself and them into the most critical corner of the fight.

While the Coldstreams, the Grenadiers, and the Yorkshire Light Infantry were holding back the Boer attack upon our right flank the indomitable Gordons, the men of Dargai, furious with the desire to avenge their comrades of the Highland Brigade, had advanced straight against the trenches and succeeded without any very great loss in getting within four hundred yards of them. But a single regiment could not carry the position, and anything like a general advance upon it was out of the question in broad daylight after the punishment which we had received. Any plans of the sort which may have passed through Lord Methuen’s mind were driven away for ever by the sudden unordered retreat of the stricken brigade. They had been very roughly handled in this, which was to most of them their [158/159] baptism of fire, and they had been without food and water under a burning sun all day. They fell back rapidly for a mile, and the guns were for a time left partially exposed. Fortunately the lack of initiative on the part of the Boers which has stood our friend so often came in to save us from disaster and humiliation. It is due to the brave unshaken face which the Guards presented to the enemy that our repulse did not deepen into something still more serious.

The Gordons and the Scots Guards were still in attendance upon the guns, but they had been advanced very close to the enemy’s trenches, and there were no other troops in support. Under these circumstances it was imperative that the Highlanders should rally, and Major Ewart with other surviving officers rushed among the scattered ranks and strove hard to gather and to stiffen them. The men were dazed by what they had undergone, and Nature shrank back from that deadly zone where the bullets fell so thickly. But the pipes blew, and the bugles sang, and the poor tired fellows, the backs of their legs so flayed and blistered by lying in the sun that they could hardly bend them, hobbled back to their duty. They worked up to the guns once more, and the moment of danger passed.

But as the evening wore on it became evident that no attack could succeed, and that therefore there was no use in holding the men in front of the enemy’s position. The dark Cronje, lurking among his ditches and his barbed wire, was not to be approached, far less defeated. There are some who think that, had we held on there as we did at the Modder River, the enemy would again have been accommodating enough to make way for us during the night, and the morning would have found the road clear to Kimberley. I know no grounds for [159/160] such an opinion — but several against it. At Modder Cronje abandoned his lines, knowing that he had other and stronger ones behind him. At Magersfontein a level plain lay behind the Boer position, and to abandon it was to give up the game altogether. Besides, why should he abandon it? He knew that he had hit us hard. We had made absolutely no impression upon his defences. Is it likely that he would have tamely given up all his advantages and surrendered the fruits of his victory without a struggle? It is enough to mourn a defeat without the additional agony of thinking that a little more perseverance might have turned it into a victory. The Boer position could only be taken by outflanking it, and we were not numerous enough nor mobile enough to outflank it. There lay the whole secret of our troubles, and no conjectures as to what might under other circumstances have happened can alter it.

About half-past five the Boer guns, which had for some unexplained reason been silent all day, opened upon the cavalry. Their appearance was a signal for the general falling back of the centre, and the last attempt to retrieve the day was abandoned. The Highlanders were dead-beat; the Coldstreams had had enough; the mounted infantry was badly mauled. There remained the Grenadiers, the Scots Guards, and two or three line regiments who were available for a new attack. There are occasions, such as Sadowa, where a general must play his last card. There are others where with reinforcements in his rear, he can do better by saving his force and trying once again. General Grant had an axiom that the best time for an advance was when you were utterly exhausted, for that was the moment when your enemy was probably utterly exhausted [160/161] too, and of two such forces the attacker has the moral advantage. Lord Methuen determined — and no doubt wisely — that it was no occasion for counsels of desperation. His men were withdrawn — in some cases withdrew themselves — outside the range of the Boer guns, and next morning saw the whole force with bitter and humiliated hearts on their way back to their camp at Modder River.

The repulse of Magersfontein cost the British nearly a thousand men, killed, wounded, and missing, of which over seven hundred belonged to the Highlanders. Fifty-seven officers had fallen in that brigade alone, including their Brigadier and Colonel Downman of the Gordons. Colonel Codrington of the Coldstreams was wounded early, fought through the action, and came back in the evening on a Maxim gun. Lord Winchester of the same battalion was killed, after injudiciously but heroically exposing himself all day. The Black Watch alone had lost nineteen officers and over three hundred men killed and wounded, a catastrophe which can only be matched in all the bloody and glorious annals of that splendid regiment by their slaughter at Ticonderoga in 1757, when no fewer than five hundred fell before Montcalm’s muskets. Never has Scotland had a more grievous day than this of Magersfontein. She has always given her best blood with lavish generosity for the Empire, but it may be doubted if any single battle has ever put so many famihes of high and low into mourning from the Tweed to the Caithness shore. There is a legend that when sorrow comes upon Scotland the old Edinburgh Castle is lit by ghostly lights and gleams white at every window in the mirk of midnight. If ever the watcher could have seen so sinister a sight, it should have been on this, the fatal night of December 11, 1899. As to the Boer loss it is impossible to determine [161/162] it. Their official returns stated it to be seventy killed and two hundred and fifty wounded, but the reports of prisoners and deserters placed it at a very much higher figure. One unit, the Scandinavian corps, was placed in an advanced position at Spytfontein, and was overwhelmed by the Seaforths, who killed, wounded, or took the eighty men of whom it was composed. The stories of prisoners and of deserters all speak of losses very much higher than those which have been officially acknowledged.

In his comments upon the battle next day Lord Methuen is said to have given deep offence to the Highland Brigade by laying the blame of the failure upon them, and stating that had they advanced instead of retiring the position would have been taken. The attack, he held, had been correctly timed, and only needed to be pushed home. The reply to this is the obvious one that the brigade had certainly not been prepared for the attack, and that it is asking too much that unprepared men after such terrible losses should carry out in the darkness a scheme which they do not understand. From the death of Wauchope in the early morning, until the assumption of the command of the brigade by Hughes-Hallett in the late afternoon, no one seems to have taken the direction. ‘My lieutenant was wounded and my captain was killed,’ says a private. ‘The General was dead, but we stayed where we were, for there was no order to retire.’ That was the story of the whole brigade, until the flanking movement of the Boers compelled them to fall back.

The most striking lesson of the engagement is the extreme bloodiness of modern warfare under some conditions, and its bloodlessness under others. Here, out of a total of something under a thousand casualties, seven [162/163] hundred were incurred in about five minutes, and the whole day of shell, machine-gun, and rifle fire only furnished the odd three hundred. So also at Lombard’s Kop the British forces (White’s column) were under heavy fire from 5:30 to 11:30, and the loss again was something under three hundred. With conservative generalship the losses of the battles of the future will be much less than those of the past, and as a consequence the battles themselves will last much longer, and it will be the most enduring rather than the most fiery which will win. The supply of food and water to the combatants will become of extreme importance to keep them up during the prolonged trials of endurance, which will last for weeks rather than days. On the other hand, when a general’s force is badly compromised, it will be so punished that a quick surrender will be the only alternative to annihilation.

On the subject of the quarter-column formation which proved so fatal to us, it must be remembered that any other form of advance is hardly possible during a night attack, though at Tel-el-Kebir the exceptional circumstance of the march being over an open desert allowed the troops to move for the last mile or two in a more extended formation. A line of battalion double-company columns is most difficult to preserve in the darkness, and any confusion may lead to disaster. The whole mistake lay in a miscalculation of a few hundred yards in the position of the trenches. Had the regiments deployed five minutes earlier it is probable (though by no means certain) that the position would have been carried.

The action was not without those examples of military virtue which soften a disaster, and hold out a brighter promise for the future. The Guards withdrew [163/164] from the field as if on parade, with the Boer shells bursting over their ranks. Fine, too, was the restraint of G Battery of Horse Artillery on the morning after the battle. An armistice was understood to exist, but the naval gun, in ignorance of it, opened on our extreme left. The Boers at once opened fire upon the Horse Artillery, who, recognising the mistake, remained motionless and unlimbered in a line, with every horse, and gunner and driver in his place, without taking any notice of the fire, which presently slackened and stopped as the enemy came to understand the situation.

R.A.M.C. [Royal Army Medical Corps] collecting wounded. Wash drawing signed by E. Bouard. Click on image to enlarge it.

But of all the corps who deserve praise, there was none more gallant than the brave surgeons and ambulance bearers, who encounter all of the dangers and enjoy none of the thrills of warfare. All day under fire these men worked and toiled among the wounded. Beevor, Ensor, Douglas, Probyn — all were equally devoted. It is almost incredible, and yet it is true, that by ten o'clock on the morning after the battle, before the troops had returned to camp, no less than five hundred wounded were in the train and on their way to Cape Town.

Last modified 17 December 2013