ickens wrote A Christmas Carol (1843) in order to appeal to the collective conscience of the complacent middle-classes, to educate his readers as to the sufferings of the poor, and to argue for a new, compassionate understanding of society’s inequalities and its unwholesome obsession with money. His target, in particular, was laissez-faire economics and the worst excesses of personal greed, showing how, in the transformation of the emblematic figure of Scrooge, it is possible for capitalist employers to move from a position of profit-driven exploitation of their workers to one of generous compassion. Published on 19 December 1843, A Christmas Carol was a carefully calculated reminder of Christian virtues, and how, especially on the anniversary of Christ’s birth, charity should be the prime constituent of a moral life.

This didacticism has been the subject of innumerable readings, and there is no doubt that Dickens’s small book had a considerable impact on its original readership in the desperate period known as the ‘Hungry Forties.’ In keeping with the ‘Condition of England’ novels of the time – notably Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton (1848) and Benjamin Disraeli’s Sybil (1845) – it urges for a moral, rather than a political solution to the problems of class-conflict. That stance seems naïve to modern commentators, and it is often noted that the text has the qualities of a fable or fairy-tale, even if Dickens presents a harsh and realistic treatment of the sufferings of the poor, as exampled by the pathetic figures of Want and Ignorance and Tiny Tim.

It is not the case, however, that A Christmas Carol can be purely explained as a didactic tract. Another way of reading it, and one relatively undeveloped, is to focus on the book’s psychology and Dickens’s treatment of his main character; though Scrooge’s spiritual progress is from greed to generosity, it is also possible to interpret his development as a matter of mental health and his recovery, we might say, from madness, or at least from a position of being possessed by destructive irrational beliefs. Dickens inflects his presentation of the moral fable with a sense of this possibility, and it is worth considering as another dimension of the author’s writing. In order to make sense of Scrooge’s personality we can draw on a number of theories, some derived from modern psychoanalysis and some from theorizing of the nineteenth century.

Scrooge’s Mental Condition: Bad or Mad?

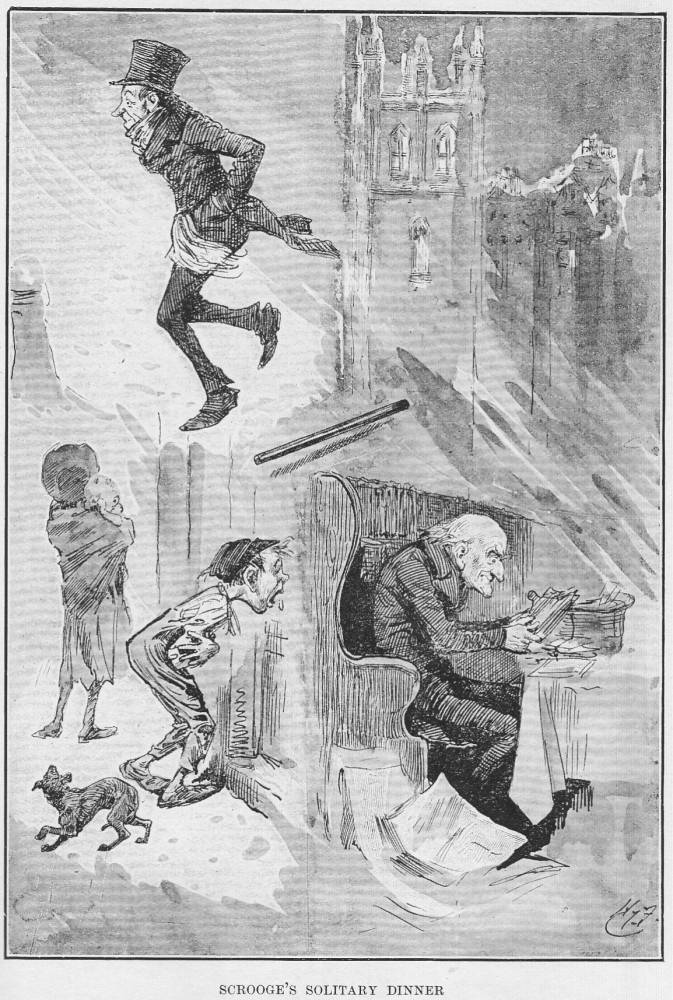

Harry Furniss's illustration shows a dog shrinking away from Scrooge in the street.

Before he reforms, Scrooge’s behaviour is morally abhorrent: motivated by avarice and obsession with his personal wealth, he has contempt for everyone, exudes a threatening aura – even the blind men’s dogs guide their masters away from him (Dickens 4) – is rude, cruel and abrasive, withholds a decent wage from Bob Cratchit and thinks, in line with Malthusian theory, that the poor are just ‘surplus population’ (14) with no right to life. As Dickens caustically remarks, he is a ‘covetous old sinner’ (3), a man indifferent to society and completely lacking in any personal morality. His compound of vices focuses the author’s concern with a multiplicity of related social evils; however, Scrooge’s psychological traits are so complex and strange that they suggest personality disorders and psychosis as much as immorality.

Any diagnosis of his character in clinical terms would have to consider a number of alternatives or co-morbid conditions. In common terms, Scrooge would have to be described as sociopathic; devoid of empathy and antagonistic, highly manipulative and only concerned with others as means to generate profits, he has no personal relationships, no interest in revealing anything about himself, and only exists in terms of a narcissistic self-absorption. In Dickens’s telling description, he is as closed and isolated as a shellfish, ‘secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster’ (3): a cold fish indeed. His physical coldness exemplifies his emotional coldness; he imposes a pariah status on himself and feels himself to be justified, regarding the world to be out of step with his chosen lifestyle. ‘But what did Scrooge care [?]’ Dickens inquires as to why he lives in this way, and answers his own question: ‘It was the very thing he liked’ (5).

Such behaviour is deeply aberrant and might even be described as psychopathic. The concept of psychopathy was developing in the nineteenth century, when it was described as ‘moral insanity’ (Millon and Simonsen 6–8), and in a general sense Dickens’s character could be said to conform to at least some of the criteria of this severe illness. Andrea L. Glenn and Adrian Raine define the psychopathic condition as a combination of features that includes being ‘grandiose and self-centred’ with a ‘pronounced lack of empathy,’ a ‘disregard for social norms’ and a ‘callous’ unfeeling attitude (3), all features that can be identified in Scrooge’s beahviour. It is equally possible to imagine Scrooge as engaging in the criminality that lies at the heart of the psychopathic condition. Dickens scathingly presents him as if he were a criminal as he indifferently watches the suffering of the poor, but his pursuit of wealth might easily involve petty swindles and deception; it is hard to see how someone so dishonest with himself could be honest with others. At the same time, Scrooge does not possess the superficial charm and humour associated with the illness, and makes no attempt to present himself in anything other than the most misanthropic and hostile terms; the model half-fits.

But there are other possibilities too. Significant, perhaps, is Scrooge’s introversion and pessimism. These are signs of depression or, likelier, manic-depression or bipolar disorder, conditions which involve a repeating cycle of low mood alternating with elation, and with rapid transitions between the two. Scrooge certainly undergoes a spectacular transformation, moving from self-destructive unhappiness to a condition of sentimental euphoria, as ‘happy as an angel’ (Dickens 153). This process is of course fable-like, but viewed psychoanalytically it bespeaks mental instability, the very fabric of a depressive disorder. Edmund Wilson (1941) argues for this diagnosis of the character, noting how Scrooge is ‘a very uncomfortable person’ jostled between extremes, who would soon ‘relapse’ (64) into his usual gloom following his period of happiness.

Another illustration by Harry Furniss gives a glimpse of Scrooge's lonely childhood.

Scrooge’s condition might also be viewed not so much as depression, as such, as its typical co-morbid condition – anxiety. The causes of his behaviour could be his traumatized childhood – motherless and rejected by his father – and Dickens several times suggests that his mindset is predicated on insecurity and the need to protect himself. When he breaks with Belle, for instance, he comments how ‘there is nothing on which the world is so hard as poverty’ (Dickens 65). His psychological mistake, however, is to confuse material and emotional wealth, a familiar behaviour for those who suffer childhood trauma and insecurity and turn to selfish materialism because it enables the sufferer to take possession and control of their lives: objects and numbers can be controlled, emotions, and the behaviour of others – such as Scrooge’s unfeeling father – cannot.

Control is one of the key elements of Scrooge’s disordered personality and, in line with those battling anxiety, imposes a high degree of regulation upon himself in order to cope, ordering his world into strict routines in which money acts as a surrogate for love. To avoid facing his inner hurt, he most of all contains his feelings within an inflexible persona, a notion Dickens conveys in his emphasis on Scrooge’s stiff gait and flint-like hardness. (3).

Such internalization can be understood in terms of Freudian repression, and Scrooge’s illness is in many ways a case-study of an unhealthily contained inwardness which is only released when the ghosts appear. Put in Freudian terms, Scrooge’s condition is a prime example of uncanniness, a form of mental instability and delusion, in which his mind is already aware of certain thoughts and feelings that have been kept in check by anxiety so that the familiar seems momentarily to be unfamiliar. As Stephen Prickett observes, ‘the spirits … cannot be said anywhere to show Scrooge anything that he does not in one sense already know’ (57).

Viewed thus, the ghosts are mental emanations from Scrooge’s unconscious mind rather than external agencies, and the urgency with which they appear exemplifies the Freudian notion of thoughts as an energy which becomes ever more destructive if it is not released. The appearance of the ghosts, his personified thoughts, save him from mental breakdown by allowing him to confront all he has suppressed. His self-therapy works, and he re-establishes a mental equilibrium which enables him to recover.

The Context of Victorian Psychology: Money and Madness

Scrooge’s personality might thus be interpreted within a number of theoretical models. Moreover, it is instructive, as we try to define his condition (s), by drawing on understandings of mental illness in Dickens’s own time. A significant part of this writing was concerned with the psychology of avarice and can be used to analyse Scrooge’s disordered, fetishistic relationship with money.

Scrooge’s personality, formed by his obsession with personal wealth, yields directly to the notion, as commonly voiced in the Victorian age, and expressed in texts as diverse as Henry Maudsley’s studies of mind and moral explorations of greed such as those by Sumner Merryweather, that avarice was a destructive mental affliction or monomania. In Merryweather’s words, ‘avarice [is] a prolific cause of insanity,’ a ‘mania’ and ‘mental disease’ or ‘mental aberration.’ (149–150). Viewed in these terms Scrooge can be described as insane rather than bad, and it is remarkable to see how closely his condition corresponds with the details of contemporaries’ studies.

First of all, Scrooge’s love of money is an exact fit with the obsessiveness that is identified by Victorian theorists of the ‘madness.’ Avarice, Maudsley remarks, can ‘unhinge the merchant’s mind’ and lead to an over ‘eager passion’ (Physiology and Pathology of the Mind, 205) or appetite for lucre. The mentally deranged miser, so Thomas Dick further observes, is entirely focused on ‘the accumulation of wealth,’ living a life in which his ‘whole affections [are] absorbed’ (47) in his money-quest. Indeed, this is exactly what happens to Scrooge; as Belle sadly reflects, his ‘idol’ is ‘a golden one,’ displacing loving relationships (Dickens 65). Driven by his obsession, Scrooge further complies with the clinical model of the miser who will do anything in order to acquire more wealth and, once again, Dick’s diagnosis is an exact definition of the character’s rapaciousness. In Dick’s explanation, a person afflicted with this ‘abnormal’ condition is ‘hard and griping in every bargain … grinds the faces of the poor, and refuses to relieve the wants of the needy’ (47), a catalogue of symptoms which is precisely echoed by Dickens’s description of Scrooge as a ‘squeezing, wrenching, grasping, clutching old sinner’ (Dickens 3) who refuses to give money to the charity men, hates the poor, and resents giving Bob a holiday, a concession he regards as the same as having his pocket picked.

Scrooge also conforms to the notion of money-obsession as being directed by antagonism in which the miser believes he is embattled and surrounded by enemies who wish to harm him, and views the taking of his money as an assault. James Glassford notes how the ‘strange infatuation’ (57) with money is a form of warped self-protection in which the miser ‘believes that mankind [has] conspired to defraud him’ and is ‘delighted at the idea of saving’ (62): no better definition could be given of Scrooge’s cold repudiation of those who press him for money, whom he regards as thieves, asking only ‘to be left alone’ (Dickens 13). This fearfulness is intermixed, moreover, with egotism; the miser feels threatened, but at the same time is self-absorbed, arrogant and unfeeling. The condition, Maudsley argues, is driven by ‘self-regarding egoism’ (285) which ‘put [s] the individual out of sound and wholesome relations with his fellows’ and can only ‘isolate him’ (Body and Will, 285–6). Scrooge is certainly egotistical, takes pleasure in his abrasive dismissal of Fred and the charity men, and is only concerned with his own well-being.

Furniss shows Scrooge, shut off from the world, supping on gruel.

Scrooge’s obsessive greed, emotional coldness and psychological isolation could all be explained, in other words, as aspects of a well-defined psychosis which was current in understandings of the mid-Victorian period. Most of all, he complies with the notion of avarice as absurdly self-defeating because it is not a means to achieve self-enrichment but a fixation on money that can never be spent. The miser, Glassford explains, is motivated by the desiring of money for ‘its own sake’ (54); as Dick continues, he ‘has no intention of enjoying such wealth’ (20) and ‘starves himself in the midst of riches and plenty’ (48). And, of course, this is what Scrooge does: he lives like a pauper in a run-down house, eats gruel (the cheapest food he can find), is always cold – fires are expensive – and is too parsimonious to live comfortably when he could be very comfortable indeed. A decent diet, fuel and homely lodgings would all cost him and he is purely controlled by his compulsion not to spend. In the words of Glassford, ‘he cannot be said to possess wealth; wealth possesses him’ and acts ‘like a fever which burns and consumes him’ (57).

It seems to make a good fit, and Dickens may have read the accounts of at least some of the theorists mentioned here, refiguring their notions in A Christmas Carol. Rightly speaking, Scrooge can be read in these terms as someone afflicted with chrometophobia – an obsessive-compulsive illness which presents in the fear of spending money. No doubt, Scrooge is a prime example of this pathology for whom, as we have seen, wealth only exists in the abstract and not to be spent; spending it produces resentment, anxiety, and anger.

So how, finally, should Scrooge’s character be read? It seems that he fits several models of pathological disorder, both modern and Victorian, and could be interpreted as a sufferer possessed with multiple conditions coexisting in a deadly blend of ‘avarice disorder,’ narcissism, depression and anxiety. The ghosts enable him to face the negative thoughts he has so long repressed, but is their visitation, trawled from his seething unconscious mind, a cure? As noted earlier, Edmund Wilson thinks he would simply relapse, and it likely that a man so psychotic and afflicted would, in reality, need a much more developed therapy than the self-directed counselling of a single night.

Links to Related Material

- Victorian Psychology

- Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol, 1843: An Introduction

- Scrooge (general discussion, but again with a psychological slant)

- The Christmas Books of Charles Dickens — A Christmas Carol and Other Stories

Bibliography

Primary

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. London: Chapman & Hall, 1843.

Disraeli, Benjamin. Sybil. London: Colbourn, 1845. 3 Vols.

Gaskell. Elizabeth. Mary Barton. 2 Vols. London: Chapman & Hall, 1848.

Secondary

Dick, Thomas. An Essay on the Sin and the Evils of Covetousness. New York: Robinson, 1836.

Freud, Sigmund. The Uncanny. 1909; London: Penguin, 2003.

Glassford, James. Covetousness Brought to the Bar of Scripture. London: Johnstone, 1836.

Glenn, Andrea L., and Raine, Adrian. Psychopathy: An Introduction to Biological Findings and Their Implications. New York: New York University Press, 2014.

Maudsley, Henry. Body and Will. New York: Appleton, 1884.

Maudsley, Henry. The Physiology and Pathology of the Mind. New York: Appleton, 1867.

Merryweather, F. Somner. Lives and Anecdotes of the Misers. London: Simpkin Marshall, 1850.

Psychopathy, Anti-Social, Criminal, and Violent Behaviour. Eds. Theodore Millon, Erik Simonsen. New York: Guilford Press, 1998.

Prickett, Stephen. Victorian Fantasy. Waco: Baylor University Press, 2005.

Wilson, Edmund. The Wound and the Bow. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1941.

Created 15 July 2023