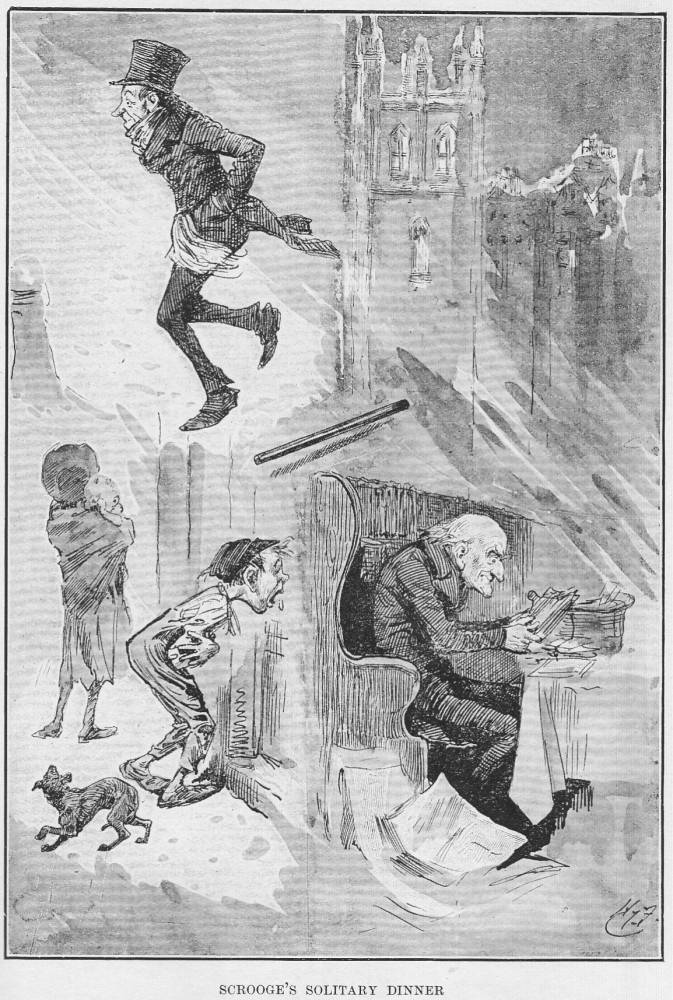

Scrooge's Solitary Dinner

Harry Furniss

1910

13.8 x 9.5 cm (5 ⅜ by 3 ¾ inches), framed.

Third illustration for A Christmas Carol in The Christmas Books, Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910), Vol. VIII, facing page 8.

This amalgam of four scenes suggests the rapid succession of related stills in a magic lantern show, juxtaposing Scrooge's self-satisfied contemplation of his banker's book after supper with the social engagement of people outside the "melancholy tavern" (and outside his class). [Commentary continued below.]

[Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use the images on this page without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Details

- Bob Cratchit cheerfully walks home through Cornhill

- The gothic church tower near Scrooge's office

- The tailor's lean wife and baby; a raw-nosed street-boy

- Scrooge dines at a melancholy tavern

Passages Realised

Meanwhile the fog and darkness thickened so, that people ran about with flaring links, proffering their services to go before horses in carriages, and conduct them on their way. The ancient tower of a church, whose gruff old bell was always peeping slyly down at Scrooge out of a Gothic window in the wall, became invisible, and struck the hours and quarters in the clouds, with tremulous vibrations afterwards as if its teeth were chattering in its frozen head up there. The cold became intense. In the main street at the corner of the court, some labourers were repairing the gas-pipes, and had lighted a great fire in a brazier, round which a party of ragged men and boys were gathered: warming their hands and winking their eyes before the blaze in rapture. The water-plug being left in solitude, its overflowing sullenly congealed, and turned to misanthropic ice. The brightness of the shops where holly sprigs and berries crackled in the lamp heat of the windows, made pale faces ruddy as they passed. Poulterers' and grocers' trades became a splendid joke; a glorious pageant, with which it was next to impossible to believe that such dull principles as bargain and sale had anything to do. The Lord Mayor, in the stronghold of the mighty Mansion House, gave orders to his fifty cooks and butlers to keep Christmas as a Lord Mayor's household should; and even the little tailor, whom he had fined five shillings on the previous Monday for being drunk and bloodthirsty in the streets, stirred up to-morrow's pudding in his garret, while his lean wife and the baby sallied out to buy the beef. [Stave One, "Marley's Ghost," pp. 9-10]

The office was closed in a twinkling, and the clerk, with the long ends of his white comforter dangling below his waist (for he boasted no great-coat), went down a slide on Cornhill, at the end of a lane of boys, twenty times, in honour of its being Christmas Eve, and then ran home to Camden Town as hard as he could pelt, to play at blindman's-bluff.

Scrooge took his melancholy dinner in his usual melancholy tavern; and having read all the newspapers, and beguiled the rest of the evening with his banker's-book, went home to bed. He lived in chambers which had once belonged to his deceased partner. They were a gloomy suite of rooms, in a lowering pile of building up a yard, where it had so little business to be, that one could scarcely help fancying it must have run there when it was a young house, playing at hide-and-seek with other houses, and forgotten the way out again. It was old enough now, and dreary enough, for nobody lived in it but Scrooge, the other rooms being all let out as offices. The yard was so dark that even Scrooge, who knew its every stone, was fain to grope with his hands. The fog and frost so hung about the black old gateway of the house, that it seemed as if the Genius of the Weather sat in mournful meditation on the threshold. [Stave One, "Marley's Ghost," pp. 10-11]

Commentary

Here, the social isolate and inveterate miser, without the benefit of any friends and relations, habitually dines alone. In contrast, a blithe Bob Cratchit (upper left), instantly recognisable by his long comforter, trots homeward through Cornhill, smiling to himself, probably at the prospect of sharing Christmas Eve with his numerous family. Although Dickens merely mentions the church tower opposite Scrooge's counting-house in passing, Furniss uses the decaying church tower to establish the urban setting and imply the threat to the Christian message of the brotherhood of man that Scrooge's belief in the cash nexus, becoming broadly accepted in the mid-nineteenth century, entails. The images of the tailor's wife, out procuring dinner, and the street boy with the frozen nose suggest the vitality of urban life, in contrast to Scrooge's anti-social, solitary existence in his "melancholy" tavern.

Hammerton, Furniss's editor, seems to have had only the very short excerpt beginning with "the clerk, with the long ends" and ending with "went home to bed" (pp. 10-11) in mind, but clearly Furniss himself draws on descriptive material from pages 9 through 11, ending just before the transformation of the door-knocker into Marley's face. An apparently non-textual detail is the cowering dog of indeterminate breed (lower left), who appears again in another composite lithograph, "Phantoms in the Street" (facing p. 33), a detail based on an earlier passage, "Even the blind men's dogs appeared to know him [Scrooge]; and when they saw him coming on, would tug their owners into doorways and up courts" (4).

"The ancient tower of a church, whose gruff old bell was always peeping slily down at Scrooge out of a gothic window in the wall" (9) has little narrative significance here, and one wonders precisely why Furniss included this particular element of the setting, unless to present a thematic contrast (already considered) or to prepare the reader for this important setting in the second of the Christmas Books, The Chimes, the scene of Trotty Veck's supernatural encounter and dream vision. Perhaps it represents one of Furniss's sixty-three magic-lantern slides mentioned in a February 1905 advertisement in the Dickensian (Cordery 4) as part of his platform entertainment entitled "A Sketch of Boz." Because it seems to suggest a precise location for Scrooge's counting-house near Mansion House, Dickens critics have attempted to identify precisely which church Dickens had in mind, so that Furniss's sketch might suggest to which location the illustrator inclined. While Frank S. Johnson in his Winter 1931-32 Dickensian article "About 'A Christmas Carol'" (cited by Hearn) would later propose St. Michael's, probably on account of its proximity to London's Royal Exchange (to which Scrooge resorts daily), A. E. Berresford Chancellor in The London of Charles Dickens (London: Grant Richards, 1924, pp. 280-81, as cited by Guiliano and Collins, I: 838) proposes either St. Dunstan's "between Tower Street and Upper Thames Street" or St. Mary Alderberry "between Bow Lane and what is now Queen Victoria Street" — the former supporting a location for Scrooge's counting-house in Cross Lane, St. Dunstan's Hill, which would square with Dickens's referring to "the good Saint Dunstan" (10). Whatever the location

Although Leech in the original edition depicted Bob Cratchit just once, in the tailpiece as he and his reformed employer share a glass of Smoking Bishop before Scrooge's fireplace, Sol Eytinge in Ticknor and Fields' twenty-fifth anniversary edition (1868) and the Household Edition illustrators Fred Barnard and E. A. Abbey depicted the cheerful, underpaid clerk as a foil to his curmudgeonly boss, and offer a number of interpretations of him.

In contrast, Harry Furniss does not yield to the Victorian taste for sentimental scenes, and avoids (except in his title-page vignettes) the Cratchits and their Christmas pudding, Tiny Tim and his crutch, and Bob toasting Scrooge as founder of the feast, all found in earlier programs of illustration. Davis notes that Furniss emphasizes the centrality of Scrooge before his reformation by basing five of his eight illustrations on Stave 1; "and none of his plates depicts Stave 5" (121). Although the narrative accompanying Scrooge's Solitary Dinner begins with Bob's leaving the office and ends with Scrooge's contemplation of his bank-book, Furniss presents the four characters and three settings (the streets, the church tower, and the interior of the tavern) simultaneously, and so challenges the reader proleptically (i. e., in anticipation) to resolve the sequence and determine the connections between these discrete textual moments consolidated into a single lithograph.

Related Illustrations from Earlier Editions (1868, 1876, 1878)

Left: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Scrooge and Marley's (1868); right: E. A. Abbey's "Went down a slide on Cornhill twenty times. . ."

Left: "Mr. Scrooge!" said Bob; "I'll give you Mr. Scrooge, the Founder of the feast!" (1876); right: Fred Barnard's He had been Tim's blood-horse all the way from church, and had come home rampant (1878). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Cordery, Gareth. An Edwardian's View of Dickens & His Illustrators: Harry Furniss's "A Sketch of Boz." Greensboro, NC: University of North Carolina Press and ELT Press, 2005.

Davis, Paul. The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge. New Haven: Yale U. P., 1990.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books, illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878. Vol. XVII.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. VIII.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens. 2 vols. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. I.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustration

Harry

Furniss

Next

Created 31 May 2013

Last modified 4 January 2026