s Death and Mr. Pickwick about the actual book and its

publication history, or about the character Mr. Pickwick, or about the originator of a

bumbling Nimrod Club (Robert

Seymour), or about Charles Dickens ("Boz") and his celebrated illustrator

Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz")?

Yes.

s Death and Mr. Pickwick about the actual book and its

publication history, or about the character Mr. Pickwick, or about the originator of a

bumbling Nimrod Club (Robert

Seymour), or about Charles Dickens ("Boz") and his celebrated illustrator

Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz")?

Yes.

Jarvis tells the story of the book and its backstory though an ongoing dialogue between an avid collector of Pickwickiana, Mr. Inbelicate (whose nickname arises from an early typographical error for "indelicate"), and his secretary, Scripty (from another early printer's error for "Inscription" — "Inscriptino"). Only in the final pages of Jarvis's novel does Mr. Inbelicate describe the perfect Pickwick text, that is, its contents and physical characteristics:

The perfect Pickwick has everything — advertisements, misprints, the paper crisp and bright as the day it was printed, the type unbroken because it was printed early in the run — every wonderful thing that can make the collector's heart leap. [...] There are perhaps ten copies of Pickwick in existence which could be called first editions, and even perfection can be flawed. A good Pickwick is worth many times its weight in gold. [766]

In Charles Dickens's Pickwick Papers (April 1836-November 1837), the reader initially encounters retired businessman and amateur antiquarian Samuel Pickwick as he addresses an assemblage of like-minded seekers of local lore and peculiar but true tales from England's counties. In this mammoth novel, author Stephen Jarvis prepares today's readers for the startling revelation that this famous, first Dickens novel was in fact inspired almost entirely by Dickens's first illustrator for the picaresque serial, Robert Seymour. Thus, despite Jarvis's title, Death and Mr. Pickwick has very little to with Charles Dickens, although the publisher promotes it as "a vast, richly imagined, Dickensian work about the rough-and-tumble world that produced an author who defined an age" (Flyleaf 1). The Publishers Weekly is more accurate in its appraisal of Jarvis's novel as "an impressively imagined account of Seymour, Dickens, and a huge host of others," including the prolific illustrator George Cruikshank and his brother, the great clown Joseph Grimaldi, the sporting publisher Pierce Egan, and even coaching magnate Moses Pickwick.

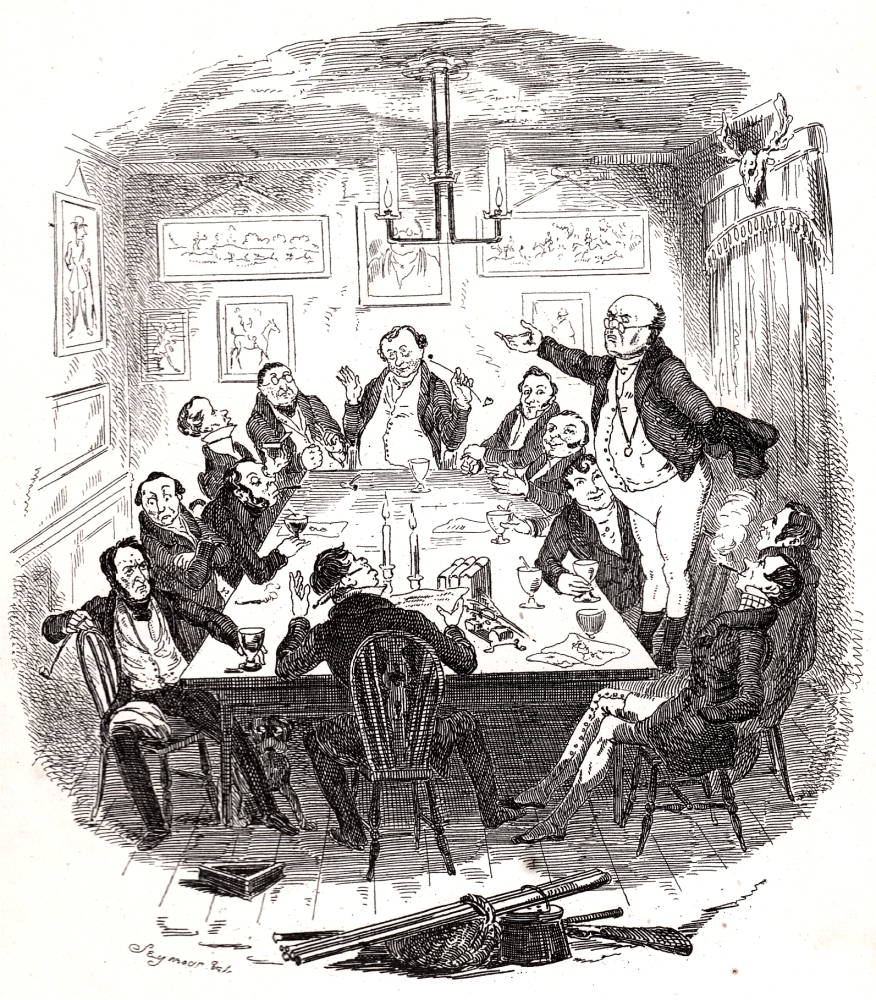

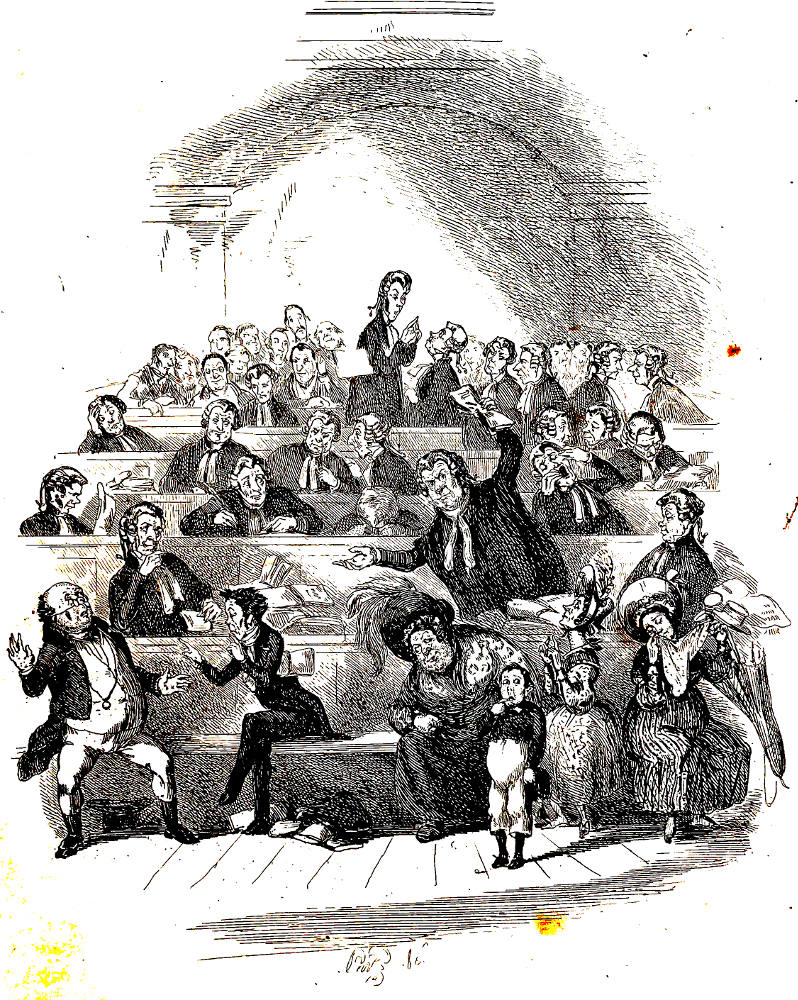

Left: Robert Seymour's original design for the first instalment of the Dickens novel: Mr. Pickwick Addresses the Club (April 1836). Chapman and Hall's original conception for Dickens's serialised novel was that there should be four illustrations rather than two. Left of centre: The Pugnacious Cabman (second plate, April 1836). Right of centre: Mr. Pickwick in chase of his Hat (May 1836). Right: The Dying Clown (based on the death of J. S. Grimaldi, April 1836). These four steel-engravings serve as the front and rear endpapers for Jarvis's 802-page novel based on the life and art of Robert Seymour (1798?-1836). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

In an address to his readers, Jarvis asserts the following about the origins of Pickwick:

This book, based upon the life of the artist Robert Seymour and the extraordinary events surrounding the creation of Charles Dickens's first novel, The Pickwick Papers, departs, at certain points, from the 'accepted' origin of Pickwick, as put forward by Dickens and his publisher, Edward Chapman. It does so for good reason.

The accepted origin is not true. (iii)

Indeed, this novel to any Dickensian is rank heresy. At one level, however, there is nothing startling to Dickensians about Jarvis's assertion that the genesis of The Pickwick Papers was Seymour's drawings, since they would readily concede that conception of a Cockney sporting club's going on monthly adventures in the countryside should be credited to Seymour. As biographer Fred Kaplan notes, for example, the publishers Chapman and Hall were already searching for someone who could provide monthly installments of text to accompany Seymour's "humorous illustrations on the subject of Cockney sporting scenes. Seymour suggested that the focus be the adventures of a club of sporting gentlemen" (77).

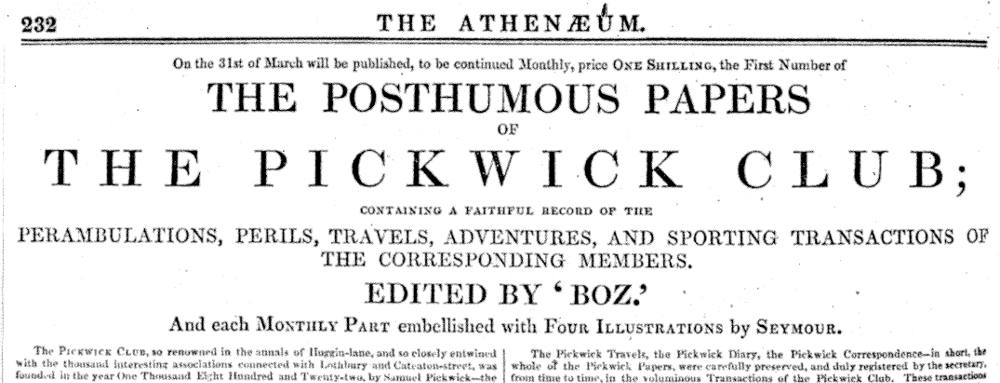

The original advertisement in the Athenaeum announcing the forthcoming monthly serial.

At thirty-eight, Seymour was a veteran of the London publishing scene, known throughout the visual society of Regency London as a prolific sketcher of outlandish metropolitan subjects and visual squibs. Charles Dickens, on the other hand, aged twenty-four, was in March 1836, as Kaplan notes, "a journeyman writer." The selling point of the monthly issue would of course be the sort of satirical illustrations that Seymour had been churning out for years. Where Kaplan and Jarvis sharply part company is on the origins of the name of the focal character, for Kaplan indicates that it was the young writer who named the work for a stagecoach owner he had met on his travels throughout England as a short-hand reporter. Kaplan and other Dickens biographers credit Dickens's humorous commentaries for the success of Seymour's project which quickly slipped beyond his artistic control.

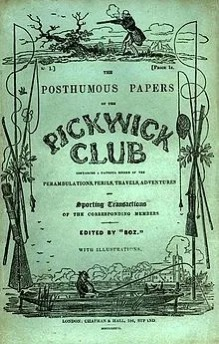

We are already at page 265 in Jarvis's novel when Seymour conceives of illustrating the far-fetched sporting tales of The Daffy Club, regulars at Aldgate's Horse and Trumpeter: "As Seymour walked under a lamp, he recalled some of his own farfetched images, of men passing themselves through mangles, of women who had grown cows' heads on their skin — what he might do if he could illustrate the tales of the Daffy Club!" (264). And what if a gullible visitor actually believed the Daffyonians' preposterous tales as the fruits of scientific enquiries made on their rural expeditions? The original monthly serial wrapper reflects precisely this conception of the Pickwickians: "Containing a faithful record of the Perambulations, Perils, Travels, Adventures and Sporting Tractions of the Corresponding Members. Edited by 'Boz.' With four illustrations by Seymour" (No. 1, April 1836). As the monthly wrapper suggests, Seymour originally conceived of Mr. Pickwick as a "Putney puntite" (298), an angler “who was not truly captivated by fishing, but used a punt merely as a floating inn, to eat, drink and smoke," part of "a sect of piscatorial philosophers whose aim is to conduct a series of experiments on solids and fluids, as well as investigating the nature of the particular gas which is evolved from the best Dutch tobacco." With that, "Seymour began sketching a picture of a fat man in a punt, a man of his favourite bespactacled type. The man was asleep, a bottle of liquor prominent in the hull, unaware in a drinken stupor that the road was bent under the strain of a fish on the hook" (301).

Jarvis dates this drawing to December 1831, coinciding with the first weekly issues of Figaro in London, a journal which regularly featured political caricatures by Seymour, and over four years before Chapman and Hall commissioned Seymour to illustrate what would become Dickens's first novel. In Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators, Jane Rabb Cohen offers a brief account of the origins of Pickwick that more or less accords with that of Jarvis, who asserts that, by 1835, the “continuing success of [Seymour’s] comic sporting sketches” prompted him to create “a plan for a series of plates depicting the mishaps of a club of Cockney sportsmen [...] The indifference of the various publishers he approached only increased his stubborn attachment to his idea, which, however derivative, he had initiated. Only Edward Chapman expressed interest.” Chapman “‘thought they might do, if accompanied by letterpress and published in monthly parts.’ The newly established firm of Chapman and Hall welcomed a chance to publish work by such a popular artist" (41).

But, of course, the form about which the London publishers were thinking, the serial, was nothing new — for as yet they had not conceived of Seymour's proposal as a novel. Stephen Jarvis has done massive amounts of research into the life and times of his quirky protagonist, and carefully lays a factual groundwork for his attribution of The Pickwick Papers to the unconventional genius of the visual arts in the Regency. Just as Dickens's title points to an era dead and gone in the "Posthumous Papers," so Jarvis details the era before the advent of the serialised novel, the narrative form with which Dickens is now primarily associated:

He [the collector, Mr. Imbelicate] reached for the top left-hand item, which possessed a thin paper spine — it was a late-seventeenth-century treatise, published piecemeal, on the subject of printing. Onwards his finger moved, to the Select Trials of the Old Bailey, published fortnightly, with accounts of sodomy, murder and highway robbery. Then works on astronomy, architecture, biography, herbs. Then Johnson's Dictionary [1756] and The Pilgrim's Progress [1679-1685]. Tobias Smollett's The Life and Adventures of Sir Launcelot Greaves came next, published in twenty-five magazine instalments and completed in 1761. 'Worthy of special mention,' he said. 'A novel which had the audacity for its beginning to be printed before the end was even written.' Here, too were remaindered works, such as one on the French Revolution which had failed to make a profit as a single volume, and was cut up into parts and resold.

'It is a bookcase of seething economic forces,' said Mr Inbelicate. 'A work produced in twenty monthly parts needs an initial outlay of just one-twentieth of the total cost,' he said, with his voice betraying an obsessive fascination which is not usually to be found in a sentence containing the words 'outlay' and 'total cost'. 'And when put on to the market, the receipts come in within a month, and are used to finance the next part!' (193)

Where Jarvis parts company with Dickens's biographers and commentators such as Cohen is the origin of the first four Pickwick episodes, for Jarvis does not merely have Seymour respond to Dickens's text, but initiate it. The surly cabman, the introduction of Jingle, the coach trip to Rochester, and the case of the mistaken identities based on Jingle's having borrowed Winkle's club jacket, and the regimental doctor’s challenge to a duel — in Death and Mr. Pickwick, these are all Seymour's inventions on the spot, in London and Rochester. So too is Seymour’s drawing, from life and well before Dickens received the commission to write the commentaries for the monthly plates, of the club members in Mr. Pickwick addresses the Club, perhaps the most famous illustration in The Pickwick Papers:

As he drank in front of the etched window [of The Goldsmith's Arms, Huggin Lane], Seymour watched a group of men traipse upstairs. They could easily be members of the Pickwick Club.

He began sketching the club meeting, with a dozen or so members gathered around a table in the upstairs room.

He knew that, in the times of Rowlandson and Gillray, he would have depicted a scene of unbridled licence and debauchery — men climbing on the table, disrobed females, guzzling until the members cast up their accounts. Those times were gone. The table he drew for the Pickwick Club, was clean, tidy and respectable. There were no women present. All members remained seated — apart from Mr. Pickwick, who as the main character, had to catch and engage the eye instantly. Seymour drew him standing on a Windsor chair, elevated above the other members, declaiming with one hand above his head — and the other hand engaged in lifting his coat-tails. The sign of the sod. That Wonk [Seymour's former gay partner] and others who moved in such circles — Seymour smiled — would attach additional significance to a hand under the coat-tails, and would have knowing grins as a result, was half the fun. (411)

At roughly halfway through the biographical novel, Jarvis appears to have made his point, namely that the originator of at least the first two instalments of The Pickwick Papers was Robert Seymour, established caricaturist, rather than Charles Dickens, the fledgling author of Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-Day Life and Every-Day People, published as separate stories between December, 1833 and December, 1836 in such periodicals as Bell's Life in London. Whatever will Jarvis cover in the remaining 391 pages?

By this point Seymour is contemplating providing a foil for his naive, middle-class merchant, a "Sancho" figure. Here is where Jarvis's thesis about the origins of The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club falls apart, as the introduction of that quintessentially Dickensian voice does not occur in instalments written before Seymour's suicide. Rather, Dickens and his third illustrator, Phiz, introduce the inimitable Sam Weller at the fifth monthly (July 1836) instalment, in the inn yard at The White Hart in Southwark, in First Appearance of Mr. Samuel Weller. Indeed, Weller’s introduction led to an immediate surge in monthly sales, for which one must credit the letterpress rather than the image, for the smart Wellerisms of the brassy boots made him an overnight sensation. At this point, one wonders why Seymour did not merely do his own writeups, and why he needed a Dickens at all.

In the novel, it is Seymour's difficulty with spelling that explains why he must find a suitable commentator for his sporting prints. He tries Hervey for his Pickwick-oriented Book of Christmas prints, but the writer cannot bring himself to see Christmas as the artist does. Seymour then considers approaching such established Regency writers as Hook, Poole, Moncrieff, and Leigh Hunt: "Someone fast — unlike Hervey" (421). The reluctant writer provides some welcome comic relief, but his appearance proves a mere digression.

Chapman and Hall, and, shortly afterward, Charles "Boz" Dickens arrive

Having described a number of figures peripheral to the novel's history, Jarvis introduces a singularly important pair, walking in the Terrace Gardens at Richmond: small, fat William Hall, and, stouter and taller, his business partner Edward Chapman. Bent on making a much more interesting newspaper, they lease an office near the Morning Chronicle offices in the vicinity of St. Clement Danes. On 5 June 1830, they offer the reading public, for sixpence a number, “their experiment in the reduction of dullness, Chat of the Week, otherwise known as the Compendium of All Topics of Public Interest” (427). Dickens’s future publishers have arrived.

Chapman and Hall had approached freelance writer Charles Whitehead to comment upon the illustrator Seymour’s clever Pickwick drawings. Terrified at the prospect of having to generate so much letterpress (12,000 words) to a gruelling schedule every month, Whitehead demurred. But he knew of a handsome parliamentary reporter nicknamed “Chatham Charlie” who had contributed to the Library of Fiction:

'I knew him when I was working at the Monthly Magazine. He’s a parliamentary journalist and he writes short stories under the pen name of Boz.'

'Ah, I think I have heard of him. Is he reliable?' (442)

The question as to whether Dickens accepts Hall’s offer unconditionally, or will counter with a proposal that he be the principal, and that Seymour merely illustrate Boz’s letterpress for Pickwick, hinges upon whether Dickens showed "The Tuggses at Ramgate" (illus.) in manuscript to Hall and Chapman before delivering it to editor John Macrone (1809–1837) for The Library of Fiction. The story is to be taken as evidence that Dickens can work rapidly and reliably to schedule. Jarvis depicts Seymour and his friends vastly entertained by an oral parlour reading of selections from Sketches by Boz, so it seems logical that Seymour agrees to have Dickens as his subordinate, the "editor" (not "writer") of The Pickwick Papers, that is, the records of the Pickwick club's rambles in the English countryside. Undoubtedly if he changes the author-illustrator relationship Chapman will incur the wrath of Seymour, whom Thomas Kibble Hervey had just let down badly by providing the letterpress for The Book of Christmas drawings only after the festive season had passed.

Left: Seymour's dramatic realisation of the story's climax, Vengeance of Captain Waters and Lieutenant Slaughter. Mr. Cymon Tuggs discovered behind the curtains, at the Waters's lodgings (31 March 1836).

Jarvis now introduces a complication that completely undermines Seymour's control over the project, even before Chapman and Hall (and their printers, Bradbury and Evans) have run the first instalment through the press. Young Boz, enthusiastic about Seymour's illustration The Dying Clown, writes eighteen lines too many as he introduces "The Tale of Dismal Jemmy," about Jem Hutley, Job Trotter's brother and a broken-down actor who has worked with Jingle. For the third chapter Dickens intends to introduce the clown’s horrific death, using it to lead off the second monthly (May 1836) number regardless of Seymour's intentions. Dickens must either cut that material, or add another page-and-a-half to the first number. "He should consult Seymour, he knew he truly should, but an emergency was an emergency" (502). By the time that Seymour consults the master printer, Hicks, Boz has already provided the extra letterpress. A furious Seymour realizes what has happened, namely that the publishers have asked Boz for more copy, and that the first number has been extended. "The realization came to Seymour that he would have to produce a drawing that was entirely governed by Boz's wishes" (508). And having read the favourable reviews of Sketches by Boz in such periodicals as The Metropolitan Magazine and the Morning Post, Edward Chapman now backs Dickens over the artist who has threatened him in his own office. Seymour, Hall argues, is a well-known artist whose drawings and paintings have been circulating for years through such illustrated magazines as Figaro in London. However, since this new short-story writer, 'Boz', has recently caused such a sensation with his London Sketches, his is the name to emphasize on the monthly wrapper:

It is. Ask yourself — would we sell more copies if Boz's name were more prominent? Now consider the circumstances. Seymour's pictures are everywhere. He is so prolific that what dies another Seymour picture mean? Not a lot. Whereas Boz — he is new, and shows every sign, from these [recent periodical] reviews you have seen, of being a great success. There shouldn't be any question as to what you should do. If Seymour quibbles — tell him exactly why we did it. [510]

Robert Seymour's Suicide and Its Aftermath

Right: Etching of Robert Seymour, circa 1830, Valerie Browne Lester, Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens, Plate 17 (Chatto & Windus, 2004)

Jarvis has laid the groundwork for Seymour’s garden suicide brilliantly, logically, showing how twenty-four-year-old Dickens has insisted that the artist redraw The Dying Clown from Dickens's interpolated piece "Dismal Jenny’s Tale," according to Boz's specifications as laid out in the tale itself. Furious as he departed from the meeting at Furnival's Inn, Seymour saw clearly, perhaps for the first time, that his control of Pickwick had evaporated. Boz, the comic writer, was now in charge, dictating that the images should support the text, and not the other way around. His wife had tried to comfort him, but in his anguished spirit he would not be mollified. Through intense limited omniscient third-person perspective Jarvis now takes us into the very consciousness of the suicidal artist:

Then he turned resolutely away from the door and approached the summer house, but did not enter. Rather, he stood at the rear, where he could not be seen. He took the note out, placed it upon the grass, and stood with one foot upon the paper. He had given the boot leather a good shine the night before.

He rammed down with the ramrod — long-engrained habits of safety made him hold the muzzle away from his face. A wry, resigned curve came to his lips. He rammed down swiftly, with confidence, as he always did, as a competent sportsman would.

The shaking came to him now as he gripped the firearm. He held the muzzle to his chest, pointed at his heart. With his other hand, he directed the ramrod towards the trigger, for it was too far away to reach unaided — the shaking was now so strong, that it took three attempts to find the required niche. Another pause. His breath came fiercely now, the fear shaking it out of his windpipe. His entire frame trembled.

He stabbed down the ramrod.

The flash from the pan flashed sideways. He fell.

He could hear less, as though his ears were filled with jewellers' cotton, yet the sound of two chattering dairymaids on their rounds streets away was clear and loud. Pebbles in the garden were smooth — he had never noticed how round and smooth before. He was on the ground, yet somehow standing above himself, a yard from where he lay. He could smell his own blood, he could almost taste it, like the time he licked a shilling as a child. (534)

The consternation of the Seymour family servant, Elizabeth Kingsbury, as she runs screaming through the house after discovering the bloody corpse is nothing compared that which reigns at the offices of Chapman and Hall. After Dickens arrives and hears the news, Hall tells him that the project is as dead as Seymour, and that he has instructed the printers at Bradbury and Evans to break up the type. Chapman tries to assuage Boz's anguish by conceding that, as the writer has just proposed, they might hire another artist. Already Dickens has roughed out the next instalment with Seymour: rook-shooting, courtship in an arbour, a cricket match, and an interesting manservant. Dickens now makes the radical proposal of extending the number of pages of letterpress and reducing the number of engravings to two. Hall rejects the notion, but Chapman is interested since they will save expenses on the artist, the steel plates, and the paper for illustrations. "I will fill the pages more vividly than any illustration" (540), vows Boz, if they pay him twenty guineas a number. This will be the longest illustrated novel ever published. Not taking any chances on having unsold stock, after Dickens leaves Hall suggests that they halve the print run to just five hundred copies. But whom will they find who can work rapidly in Seymour's style? Witty caricaturist George Cruikshank is not quick enough, nor can he draw a convincing horse. (Ironically, Cruikshank will become Dickens's illustrator for his second novel, Oliver Twist, February 1837 through April 1830.)

Seymour is laid to rest in consecrated ground at The Chapel of Ease in Liverpool Road, Islington, in an area by the north wall reserved for "executed criminals, excommunicates, unbaptised babies, and madmen who had taken their own lives" (544). Meanwhile, at the beginning of May, Jane Seymour reviews a copy of the second monthly number of Pickwick which contains only the last three Seymour plates as it appears he has destroyed the fourth.

Buss's Dismissal, Phiz's Appointment, and Sam Weller's Arrival

Even readers unfamiliar with the upshot of Seymour's death can see that the painter and occasional composer of woodcuts Robert W. Buss — reluctantly recommended by the publishers' artistic consultant, John Jackson — will not do as Seymour's replacement. But Chapman and Hall, stalling for time in order to keep the serial going, had nobody else to turn to as the art of etching required considerable practice, a deft hand, and, above all, patience, as well as proven skill as a caricaturist. Only the latter skill did the affable Buss possess in abundance. Jarvis follows Buss over three weeks of trial and error as, having failed at a number of now well-known Pickwickian studies, he approaches the assistance of expert engraver George Adcock to complete the etching he has thus far bungled: The Cricket Match. But within two weeks of submitting that awkward illustration Buss suddenly finds himself dismissed from the commission for which he never received a contract:

Messrs Chapman and Hall thanked Mr Buss for his etchings for The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club.

This was to inform Mr Buss, however, that no further illustrations would be required as the work had been placed in the hands of Mr Hablot Browne. (560)

This newcomer on the London printing scene, the "Phiz" so long associated with the works of Boz, has finally come to the attention of the desperate publishers through Jackson, who has a copy of Phiz's Royal Society of Arts medal-winning John Gilpin's Race, an illustration of a tradesman on a runaway horse. Not sparing Buss's feelings, Chapman and Hall have found the etcher-artist they require to keep the project afloat.

Many critics have already thoroughly covered the role that Phiz now assumed in the revitalised Pickwick project, notably Jane Rabb Cohen, Michael Steig, John Buchanan Brown, and Valerie Browne Lester. In the remaining third of his novel Jarvis focuses on the sequence of events following the suicide of Robert Seymour more intensely than these others, with the pro tem replacement (Buss), followed by Phiz whose involvement transforms the serial novel into a runaway bestseller.

Although at this point in the novel Jarvis seems much more interested in the adultery trial of Lord Melbourne which shorthand reporter Charles Dickens is covering, Jarvis does answer the question that so engages Dickensians: "When and how in 1836 did Phiz and Boz first meet?" Since both lived in Furnival's Inn, Holbourn, at the time — indeed, Dickens had lived there since 1834 — it seems logical that they should meet there in June 1836. However, Jarvis does not reveal much about that momentous meeting, except that Phiz has drafted an illustration from Pickwick material already published, and wants the author to examine it:

From a portfolio he brought out a drawing showing Mr. Winkle with a gun, while Tupman lay on the ground injured, having received an armful of the gun's shot. The fat boy stood behind a tree, peeking on.

Boz gave another approving smile.

'I have carefully studied Seymour's works,' said Browne, 'but I know I could not replace Seymour. I read the notice in Pickwick about his death — and I agreed with its sentiments. Seymour's death has left a blank, and a void. No one could replace him.'

'A strict interpretation of that would mean that Pickwick could not continue with Seymour.'

'I did not mean that.'

'No, I understand. Which other artists have exerted an influence on you?'

'Cruikshank. Gillray. Blake. Holbein —.'

'Holbein?'

'The Dance of Death made a strong impression on me. (576-577)

Subsequently, Phiz and his assistant from Finden's, Robert Young, work through the night to produce the plate that will change the fortunes of the Pickwick project, the etching of bootblack Sam Weller in the courtyard of the White Hart Inn, Southwark.

The bootblack was shown twisting his head around towards the lawyer, with his body turned away from the man's authority. There too was Browne's portrayal of Mr. Pickwick, with spectacles and a fine bulging stomach, in the best traditions of Seymour, but with a happier face than previously shown [...] Browne added further details to entertain the viewer, details not mentioned in Boz's words: a curious little dog at Mr. Pickwick's ankles; a haywain in the yard with a mountain of fodder topped by two boys, who had climbed up as a jape; a maid on the balcony carrying platter from which steam rose; and on a higher balcony, a line of clothes drying in the breeze. (577-578)

This will exemplify the complementary nature of the art of Dickens and Phiz, even though at this point Browne signs himself "N.E.M.O.," a pseudonym of which Dickens disapproves as "[r]ather convoluted" (578). What matters, however, is Phiz's realisation of the Sancho figure, a streetwise Cockney who will save his employer from many a scrape and even accompany him into the Fleet Debtors' Prison after his landlady, widow of an excise officer who rents rooms, sues him for breach of promise of marriage.

Left: Detail from Phiz's celebrated initial plate, First Appearance of Mr. Samuel Weller (Ch. 10, Instalment No. 5, July 1836). Center: The Pickwick Papers in its characteristic green wrapper. Right: Phiz's twenty-seventh steel engraving, The Trial (Ch. 34, Instalment No. 12, March 1837), featured the voluble Sergeant Buzfuz (right) holding forth against the defendant as Justice Starleigh presides.

Pickwickmania Seizes the Metropolis and the Popular Imagination

After Sam Weller's arrival the whole of literate London, from the lowest maid and potboy to the upper echelons of government, became obsessed with laughing over the latest green-covered Pickwick instalment and retailing the latest Wellerism. Sales jumped dramatically, with the nineteenth "double-number" achieving the unheard of figure of forty thousand copies in November 1837. Jarvis spends pages detailing the Pickwick craze:

Pickwick was a benign plague. As each new part arrived, it was a though there had been news of a victory at Waterloo, with the green-wrappered pamphlet as a banner, flourished in sheer elation that Pickwick had happened. People forgot who they were and their station in life — they simply wanted to talk to each other about Pickwick, and rejoice in its triumph. The word 'Pickwickian' was heard everywhere — and whilst this word was flexible in meaning, all understood.

Even when not talking about Pickwick, or reading it, you could tell the people who had read the latest number. They had a look in the eye. And as the publication day or the new number advanced, you saw that look more and more. (601)

Real people appear transformed by the godlike Boz as months of Pickwick go by: Justice Starleigh (based on Gaselee) and Sergeant Bompass (“Buzfuz” in "The Trial of Pickwick") being but two examples.

On 6 May 1837, Boz made a triumphant appearance at the staging of his farce Is She His Wife? or, Something Singular! at the St. James’s Theatre. The following afternoon, Mary Hogarth, Dickens’s seventeen-year-old sister-in-law, died of heart failure in her bedroom at Doughty Street. So great was twenty-five-year-old Dickens's grief that he penned no issue for June, to the general dismay of his readers:

The public came to the bookshops with their shillings in their fingers, and heard, to their astonishment, there was no Pickwick. In the thoroughfares, the street hawkers did not hold the latest green wrapper above heir caps, and met questions with a shrug, or an exasperated shaking of the head. Within an hour of the start of the working day, half the population of London knew Pickwick was not on sale. It was as though the sun had not risen. No one knew why. In the absence of facts, the world was not slow in inventing them: stories circulated in the workplaces, shops and public houses, and were elaborated upon.

It was said that the strain of producing so much laughter every month had driven the author mad. In one version of this rumour, Boz sat in a Windsor chair in a Hoxton madhouse, staring blankly ahead with a pile of unused paper in his lap and a quill held limply in his hand. (623)

Making the Monthly Numbers into a Book

Left: Phiz's first November 1837 engraving for the final "double number" of the Dickens novel: Tony Weller ejects Mr. Stiggins (Ch. 53). Left of centre: Mary and the fat boy (second plate, Nov. 1836). Right of centre: Mr. Weller and his friends drinking to Mr. Pell, or, The Coachmen Drinking the Toast (Chapter 55). Right: Pickwick and Sam Weller as Editors (Frontispiece for Part Twenty, November 1837), presenting Sam as Sancho to Pickwick's Don Quixote. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

In issuing the final, nineteenth part of Pickwick, complete with advertiser, table of illustrations, and title-page, Chapman and Hall enabled the faithful collector of monthly parts to assemble them as a book. In addition to the customary illustrations, the customer received a frontispiece, a formal title-page (of which, more later), the half-title, the dedication (to Thomas Noon Talfourd, who had advised the author on copyright), a table of contents, a list of illustrations (with the original Seymours, but minus the two by Buss), and an errata sheet "which was itself of a decidedly Pickwickian quality, as some errors had already been corrected by the compositors, and therefore the errata sheet was in error — and directions to the binder regarding the placing of illustrations" (638). The whole bundle "could be taken by a customer to a bookbinder, to be transformed into a one-volume novel." Except for two details:

[A]nyone looking at the title page issued with that final number would see that the work was no longer called The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. In a final break with Seymour, the work simply became known as The Pickwick Papers, the short version of the title which many had been using for some time. The bookbinder would throw away the full title, along with the wrappers.

There was one other change announced by that title page.

No longer were the papers merely 'Edited by Boz.'

Under the title, it said: 'by Charles Dickens.' (639)

Long after Seymour's suicide, rumours persisted of his being the originator of the concept of Pickwick, undoubtedly in part owing to his widow's efforts to be compensated by Chapman and Hall with copyright revenue. As late as the 1847 "Preface," Dickens addressed these persistent rumours obliquely by asserting his authorship:

In the course of the last dozen years, I have seen various accounts of the origin of these Pickwick Papers; which have, at all events, possessed — for me — the charm of perfect novelty. As I may infer, from the occasional appearance of such histories, that my readers have an interest in the matter, I will relate how they came into existence.

In quoting thirty-five-year-old Dickens's "recollection" of the original circumstances that gave rise to the serialised novel, Jarvis's makes much of his use of the indefinite article before 'Nimrod Club.' "The idea propounded to me was that the monthly something should be a vehicle for certain plates to be executed by Mr. Seymour, and there was a notion, either on the part of that admirable humorist, or of my visitor [...]" (655). Significantly, Jarvis has abbreviated "that admirable humorous artist" in the published version of the "Preface" to "that admirable humorist." Jarvis additionally propounds a formula for dealing with these imputations that Seymour and not Boz was the originator: the formula is not Dickens's but that of his legal advisor, John Forster (1812-76). "He looked at the word 'humourist.' That could give the public ideas about Seymour's contribution to Pickwick. He changed 'humorist' to 'humorous artist'" (655).

The material in the last part of the book is indeed diverse, including a plot by Dickens, Forster, and Chapman to buttress Boz's case against Seymour as the originator of the first two instalments of the novel by inventing an actual, Pickwick-like person from Richmond. Jarvis additionally invents a highly plausible literary detective in the person of the first artist's son, also a Robert, author of the suppositious inset autobiography "The Life of Robert Seymour, Son of Robert Seymour" (663-687). Jarvis additionally dwells on the death, in Melbourne, Australia, of Charles Whitehead, the alcoholic poet who turned down the job of providing Chapman and Hall with copy for the Seymour plates. Whitehead died of hepatitis and bronchitis on 5 July 1862 in the Melbourne Hospital, and was buried anonymously in a pauper's grave, reinforcing the significance of Jarvis's title. In November 1867 that great survivor of the coaching age, elderly Moses Pickwick, has a final drink with his superannuated drivers in the parlour of The White Hart, Bath, before it falls to the wreckers' sledgehammers. That same month, Forster saw Dickens shortly before he set off on his second American Reading Tour. In Forster's safe-keeping he leaves the eighteen-year-old letter about the mythical Pickwick original, the anachronistically attired "John Foster" of Richmond. "'It has to be ready to use, in case it is needed when I am away,' said Dickens. 'When I think of this matter, Forster, I am sick with worry'" (727). Even in the last three years of his life, contends Jarvis, Dickens remained haunted by the spirit of the actual innovator of the Pickwick Papers, Robert Seymour.

The Times [upon Dickens's death in 1870] said of Pickwick: 'We are inclined to think that this, the first considerable work of the author, is his masterpiece.' The true story of that masterpiece, the story of the greatest literary phenomenon in history, has yet to be told. (768)

In 802 pages, Stephen Jarvis has told it.

It was, even at the century mark, one of the world's famous and most printed books: "Pickwick is the most beloved book in our language. It is part of us. Part of our minds. It is no mere novel" (792) concludes Mr. Inbelicate. Indeed, only after his narrator's death does Jarvis reveal his real name: "Robert Barton," descended from Seymour's artistic chum, Wonk. Thus, Jarvis achieves some resolution and closure in a highly disparate work, that, asserts Jarvis, was Alan Turing's favourite novel. Oh, but Jarvis has not done yet: he now offers us as a kind of anti-masque, "Dismal Jemmy's lost tale," told rather than written for Pickwick, Winkle, Snodgrass, Tupan, and Sam Weller at the Leather Bottle public house in Cobham.

Related Material

- Pickwick Papers and the Development of Serial Fiction

- Dickens, Illustration, and Pickwick

- Phiz: "A Good Hand at a Horse" — Phiz's Illustrations of Horses, 1836-64

- The Complete List of Illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the Original Edition

- Clayton J. Clarke (Kyd) — Player's Cigarette Card No. 16: Mr. Pickwick (From the series of fifty, 1910)

- The Forty Cruikshank Illustrations and Half-title Vignette for Sketches by Boz

- An Introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

- A Selection of Harry Furniss's lithographs for the 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition

- Darley's 1861 Frontispieces

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition illustrations (1867)

Bibliography

[Book under review]. Jarvis, Stephen. Death and Mr. Pickwick. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015. vii + 802 pp.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1980.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Robert Seymour, R. W. Buss, and Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Chapman & Hall: April 1836 through November 1837, with a "Preface" (1847).

Dickens, Charles. Pickwick Papers. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman & Hall. Part No. Twenty (November 1837).

Kaplan, Fred. Dickens. A Biography New York: William Morrow, 1988.

Created 14 December 2024

Last modified 23 October 2025