[•• = link to material outside this site. Thanks to James Heffernan, founder and editor-in-chief of Review 19 for sharing this review with readers of the Victorian Web. — George P. Landow.]

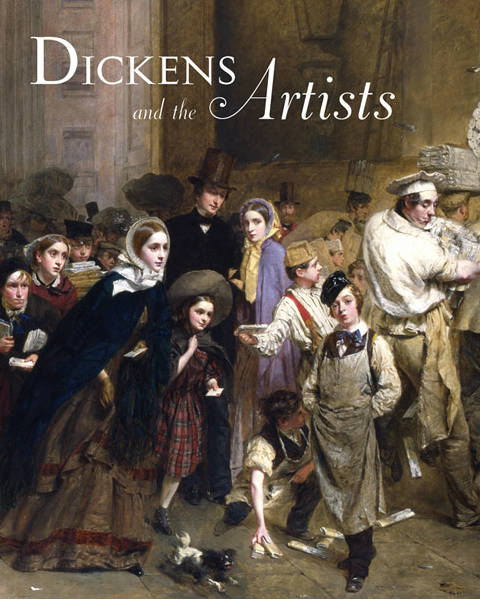

Elegantly produced and replete with appealing reproductions of many familiar Victorian paintings, this book could well grace any upmarket coffee-table. But unlike the sheen that serves to disguise the parvenu origins of the Veneerings in Our Mutual Friend, the sleekness of this volume encloses five substantial essays that were commissioned to accompany a Dickens bicentenary exhibition held at Watts Gallery in Surrey 2012. These essays celebrate and explore Dickens's views of contemporary art, the portrayal of his subjects in Victorian paintings, his influence upon nineteenth-century depictions of modern life, and his commitment to social realism, whether in his novels or in his writings about visual art.

As Nicholas Penny demonstrates in "Dickens and Philistinism," the "Inimitable" numbered among his close friends painters such as Daniel Maclise, William Powell Frith, Augustus Egg, and Clarkson Stanfield, and he exercised firm control over the illustrators who created plates for his novels. In his friendships and in his oversight of illustrations, he articulated his own firmly held views about the visual arts. As Penny argues, he also expressed those views through setting and characterization in his novels, such as in the detailed inventory of the objects with which James Carker in Dombey and Son and Sir Leicester Dedlock in Bleak House surround themselves.

Carker's Norwood villa, set in leafy countryside, its floors carpeted with rich rugs, its walls covered with choice pictures, its tables covered with richly-bound books, is, Penny argues, "emphatically a work of art" (27). Yet its luxury confirms the voluptuousness that Carker has already revealed by his lascivious looks at Edith Dombey. Just as Carker's taste in art expresses his character, so does the taste of Sir Leicester Dedlock, who cherishes pictures mostly ancient rather than modern; blinded by antiquated ideals, blind like Othello (the subject of one of his most treasured paintings), he fails to see that a subordinate is working to destroy his marriage. By contrast, very little visual art is to be found in Bleak House, home of the decent, kind-hearted Mr. Jarndyce. While Esther Summerson delightedly enumerates its abundant paintings of unusual birds, oval engravings of the months, and half-length portraits in crayons, Penny makes the important observation that the art at Bleak House "has no strong aesthetic appeal, only charming, quaint, curious things, acquired by others and retained out of family sentiment or genial indifference" (32).

Charles Dickens (1839) by Daniel Maclise. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Leonée Ormond's essay on Dickens and contemporary art focuses principally on his friendship with Daniel Maclise, who contributed illustrations to the Christmas Books and in 1839 painted arguably the finest portrait of Dickens, the "Nickleby" painting shown at left, now in the National Portrait Gallery.

In accounting for what she terms Dickens's "belief that the truth of Maclise's painting appealed to both the educated and the uneducated" (49), Ormond argues that his view was happily consistent with his distaste for pretension and dishonesty in art: for the qualities we see in the works that adorn Carker's villa or might well decorate the Veneerings' drawing room. In the eyes of Dickens, the annual exhibitions of the Royal Academy offered prime examples of such pretension and dishonesty, although in later life he spoke at the Academy's annual banquet on at least five occasions.

In the June 1850 issue of Household Words, Dickens published his most famous (or infamous) piece of art criticism: a commentary on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. He loathed John Everett Millais's Christ in the House of His Parents, aka The Carpenter's Shop (1849-50):

John Everett Millais. Christ in the House of His Parents. 1849-50. Oil on canvas, 34 x 55 in. Tate Gallery, London.

Quoting from Dickens's review of this painting, Ormond highlights his diatribe against the "hideous wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy . . . a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness, that . . . she would stand out from the rest of the company as a Monster, in the vilest cabaret in France, or the lowest gin-shop in England" (54). In quoting this description of Maclise's painting, Ormond identifies a provocative contradiction between Dickens's indelible commitment to social realism in his novels and his distaste for ugly images in the visual arts. Though he wanted the terrible, verbally graphic suffering of Jo in Bleak House to stir the reader to pity and anger, he wished to see the boy Jesus depicted on canvas as a sentimentalized, pretty-looking child. "[L]ike so much about him," Ormond concludes, his taste in art "was frequently unpredictable and idiosyncratic" (61). In the apt words of Kate Perugini (Dickens's daughter), which Ormond quotes, his love of art was surpassed by his "still greater love of nature, against which he thought that many arts ... often very gravely offended" (64).

The longest essay in this volume is Hilary Underwood's on the depiction of Dickens's subjects in Victorian art. Sensibly, Underwood observes that such depictions changed along with Victorian social values and artistic conventions. After Walter Scott, Dickens was the contemporary novelist whose works were most often depicted in painting, and for Victorians the pictorial favorites were Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop and Dolly Varden in Barnaby Rudge (interestingly, the first a vapid angel and the second a lively coquette). Underwood shows that as we move from William Holman Hunt's Little Nell and her Grandfather (1845) at left below to John Watkins Chapman's The Old Curiosity Shop (1888) at right, a late Romantic preference for landscape gives way to a later nineteenth-century taste for crowded interiors - - here a claustrophobic shop crammed with objects.

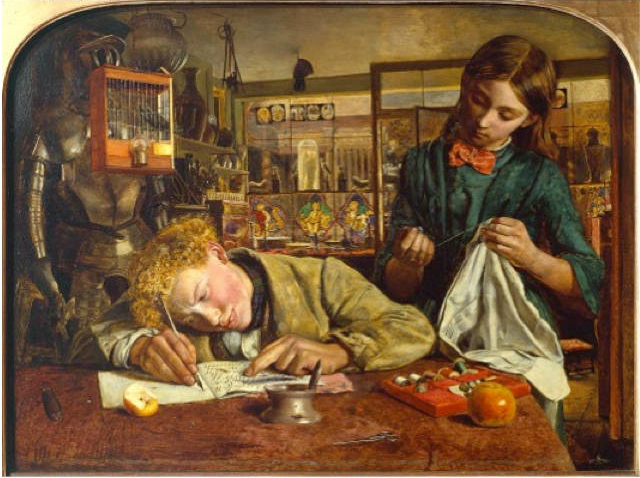

Equally crowded is the canvas of Robert Braithwaite Martineau's Kit's Writing Lesson (1852) below, which fully represents Kit's pose and gestures as he begins to write (tucked up sleeves, squared elbows, face close to the copybook, and squinting). Glossing this picture, Underwood argues that the addition of Nell doing her needlework (which she actually does not do in the text) adds "a greater depth of reference to the novel and reinforces messages about little Nell's idealized and doubly nurturing femininity" (88).

Robert Braithwaite Martineau. Kit's Writing Lesson (1852).

An elaboration of this point might have shown more fully how Little Nell, as emblem of idealized femininity, had fully entered Victorian culture by the time of Martineau's painting, and also how the sentimental adoration of Nell was eventually replaced in Victorian culture by less cloying images if not by Oscar Wilde's witty demolition of Dickens's moralizing ("One must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without laughing").

In his own essay, Mark Bills argues that Dickens's novels inspired a pictorial style of representing modern life that is most fully exemplified by the work of William Powell Frith. Of all the artists discussed in this volume, Frith probably resembled Dickens most. As Bills notes, both came from a popular British tradition of social realism, both were influenced by Hogarth, albeit in different forms and expressions, and both were artistically committed to depicting large groups of people. Epitomizing the affinity between writers and artists, their friendship expresses the modern-life school of painting. But given the cultural and social changes of a century, it was not easy for a Victorian painter or Victorian novelist to follow Hogarth's model. For later viewers and readers Hogarth's social satire needed softening, and in re-working Hogarth's themes, Dickens elided his depictions of sexuality and drunkenness except when — as in Carker's lustful thoughts about Edith — they might serve a moral purpose. Also, Dickens and Frith both defied the snobbery of those whose addiction to "high art" made them disdain vulgarly raw depictions of modern life.

Bills cogently demonstrates the affiliation of these two Victorians in discussing Frith's The Streets of London (1852), which took its inspiration from Sketches by Boz, particularly its descriptions of Covent Garden in the morning. Like Dickens, Frith depicts drunken men staggering home before sunlight, flower-girls setting up their posies for the day, and men and women striding through the Garden with heavy baskets of fruit on their heads. Without Dickens, Bills concludes, Frith could not have developed modern-life painting from its origins in Hogarthian illustrations. Just as Dickens's illustrators reflected and enhanced his own brilliant descriptions, the works of art created by painters of modern life reflected his wide-ranging vision. In sum, as Bills nicely puts it, modern-life artists saw their art as Dickens in paint.

In the final essay in the volume, "Dickens and the Social Realists," Pat Hardy examines a group of artists whose work emerged in the new illustrated journal, The Graphic, launched in 1869. Aiming to delineate poverty and social injustice, they absorbed much from Dickens's accounts of social problems in his novels: the operation of the Poor Laws, the fate of fallen women, the role of the police, and the judicial system all became subjects for these artists as they sought to visualize in a new distinctive way the miseries of modern life. If Frith and other artists of the modern-life movement chiefly aimed to depict middle-class life (Derby Day, a visit to the Post Office, and so on), these social realists were eye-witnesses to prisons, workhouses, and foundling hospitals. This essay is enhanced with superb reproductions of Samuel Luke Fildes's "Applicants to a Casual Ward" (1874), shown here in black and white:

Applicants to a Casual Ward by Sir Samuel. Luke Fildes, R. A. (1844-1927). 1874.

Pictures such as this one constitute a visual rebuke to Mr. Podsnap's comically heartless declaration in Our Mutual Friend that no one dies on the streets, and that if anyone happened to do so it would be their own fault. Wonderfully dissecting the Fildes painting, Hardy shows how its chiaroscuro challenges the viewer. With a laborer's family suffused by the light of a police lamp, it not only drapes in black the central figure, who is perhaps a widow, but also keeps her half in shadow so as to suggest her inscrutability as a homeless cipher seeking lodging on a snowy night. Like all the works reproduced in this book, Fildes's Applicants to a Casual Ward compels us to look once again — and more closely — at a familiar painting, and to see its rich affiliation with Dickens's writings.

Bibliography

Bills, Mark. Dickens and the Artists. Yale, 2012. xi + 188 pp.

Last modified 20 June 2014