[Remembering with gratitude the late James Heffernan, founder and former editor-in-chief of Review 19, who permitted us to share reviews on the site with readers of the Victorian Web. Links and illustrations have been added to this version, and the in-text citations have been adapted to our own style. Click on the two illustrations (which can be found in our own website) for more information about them, and to see larger pictures. The original review can be seen here. — Jacqueline Banerjee.]

What counts as evidence in a study of Dickens's literary style? If we are Garrett Stewart, the answer might be "private fascinations," for, as he explains, "our cognitive equipment, our linguistic register, differs from reader to reader. . . each of us is poised to be differently smitten" (xiv). For Stewart, the choice of which passage (or sentence or cluster of syllables) in a Dickens novel to close read is necessarily idiosyncratic: a result of an individual's taste, experience, and judgment — in Stewart's case, developed over a professional lifetime of brilliant and immersive reading. By contrast, if we are Michaela Mahlberg, the answer comes from the opposite end of the qualitative-quantitative spectrum: we decide what counts by literally counting. In fact, for Mahlberg who heads the CLiC Dickens Project, corpus research offers a valuable approach for analyzing literary style precisely because it brings system to the selection of passages for study. The virtue of computer-assisted research is that we may start to see something we would never have looked for. As Mahlberg puts it, "The types of patterns retrievable with the help of corpora are often not consciously accessible by our linguistic intuitions" (Corpus Stylistics and Dickens's Fiction (1).

I bring up Stewart and Mahlberg here because their divergent perspectives are foundational to Peter J. Capuano's impressive monograph, Dickens's Idiomatic Imagination: The Inimitable and Victorian Body Language. Capuano is explicitly engaged with the work of both scholars, referencing Stewart more times than any other critic (at least as far as the index suggests) and including Mahlberg and her team at CLiC Dickens in the Acknowledgments. More to the point, Dickens's Idiomatic Imagination

represents a compelling hybrid of two ways of reading that might initially seem incompatible: distant and close, digital and analogue. The book stands as an important contribution to scholarship in the Digital Humanities (broadly conceived) and, for Capuano, represents a more thorough investment in digital research methods than his previous monograph, Changing Hands: Industry, Evolution, and the Reconfiguration of the Victorian Body of 2015. Capuano describes Changing Hands as "a traditional project that has dipped one of its toes into current DH methodologies" (258). The reliance on digital methods in Dickens's Idiomatic Imagination is more robust, even as the subtitle of the book's Introduction, "Victorian Idiom and the Dickensian 'Toe in the Water,'" ironically calls back to the earlier project but with a twist: this time the toe belongs to Dickens who over his career — as Capuano goes on to claim — comes to immerse himself in an ocean of bodily idiomatic expression.Dickens's bodily idioms, figurative expressions related to the body, are at the analytic heart of the monograph; data mining provided the means to discover these idioms. In the course of his research Capuano has made — to my mind — some remarkable discoveries. The starting point is a corpus of 124 nineteenth-century novels by eleven different authors; searching the corpus for bodily idioms, Capuano found that "Victorian authors... do not use idiomatic body expressions all that much" (1). Dickens, however, is the exception (which explains why the book didn't become, for instance, "Brontë's Idiomatic Imagination"). More remarkable is the way in which certain idioms come to dominate a single novel by Dickens and then are never used in his fiction again. Capuano's corpus analytics reveal that "Dickens uses the idiom 'right-hand man' only four times in his career but only in Dombey and Son (1846-48); 'shoulder to the wheel' nineteen times but only in Bleak House (1852-53); 'brought up by hand' more than thirty times but only in Great Expectations (1860-61); 'by the sweat of the brow' and 'nose to the grindstone' a combined forty-three times but only in Our Mutual Friend (1864-65)" (6). As Capuano rightly insists, it seems highly unlikely that an analogue reading of Dickens's works would yield an evidentiary discovery so peculiar and suggestive.

And yet, as Capuano also insists, this evidence represents the starting point for an interpretive project that uses close reading, philological research, examination of manuscripts, and biographical context to give us a new understanding of Dickens's creative process and of the interplay between language and theme in several of Dickens's most sophisticated novels. As Capuano demonstrates, the fact of Dickens's affinity for idioms is much less interesting and important than the way he uses particular idioms as organizing ideas for his novels. Analysis of this sort brings us closer to an understanding and appreciation of Dickens's prose style, which is never ancillary to story and theme; on the contrary, language fuels Dickens's imagination. Capuano is interested in the way in which even a small lexical unit, an overlooked idiom, might help shape a novel's thematic development. Moreover, he wants to make the case that the aspect of Dickens's prose that his early critics were most dismissive of — his use of vulgar language or slang, his easy adoption of the vernacular — is entirely compatible with literary artistry. "[R]eaders really should," Capuano argues, "expect to find abstract thought and sophisticated ideas constellating around Dickens's idiomatic language" (11).

After the introduction, which explains the methodology and lays out the argument in broad strokes, four substantial chapters follow, each of which serves as a test case of sorts, exploring the role a particular body idiom plays in a single novel. Chapter 1, focusing on the figure of the "right-hand man" in Dombey and Son, sets up a pattern that Capuano adheres to in the succeeding chapters. First he establishes the singularity of the idiom. After describing the changing meaning of the idiom over time (from the use of the phrase in its literal sense to its later figurative meanings), Capuano traces the history of the idiom's usage by searching a corpus consisting of the combined databases of British Periodicals and the British Library Newspapers Digital Archive. For "right-hand man," as for Dickens's other signature bodily idioms, what the evidence reveals is a spike in the idiom's appearance just before or right around the time of the novel's composition. As Capuano notes, such coincidences are perhaps less surprising when we recall Dickens's reliance on colloquial language when crafting his fictional prose, his preternatural ability to hear and adapt the idioms of his time (8-9; 132).

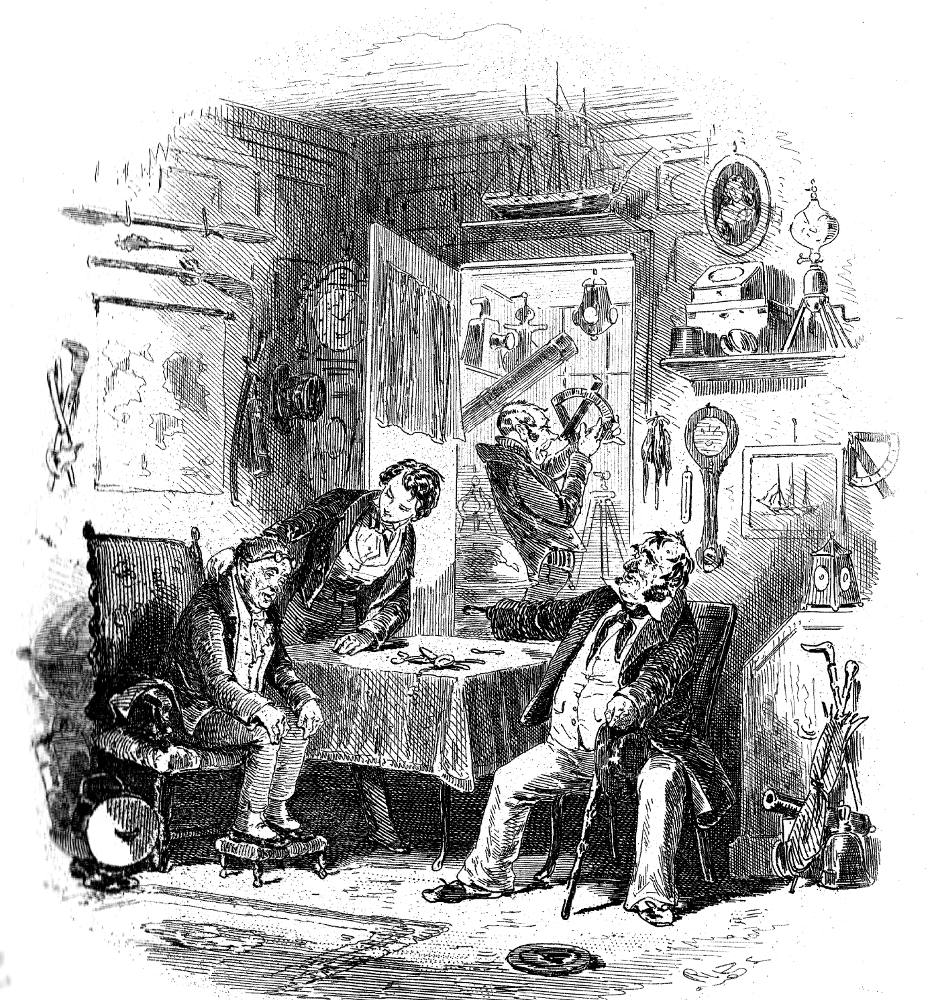

But again, the fact of any one idiom's appearance is less important than the work the idiom does in the novel. Among the achievements of the monograph is Capuano's careful analysis of the thematic implications of each idiom and of what Capuano calls "idiom absorption" in the novel. "Idiom absorption" isthe process whereby the idiom "once articulated and repeated, becomes absorbed into the text whole cloth in such a way that its literalization, abstraction, or even its explicit violation emerges as new agents for thematic innovation" (49). As a result, each idiom "operates as . . . [a] unifying force" that influences how Dickens "imagines characterization, narrative voice, plotting, and most importantly thematic schema" (37). In the case of Dombey, surrogacy or substitution is the thematic concern that the figure of the right-hand man allows Dickens to reflect on and probe. While the idiom is used explicitly in reference to Carker, Dombey's indispensable manager, the application is ultimately ironic since Carker fails to uphold his principal: his surrogacy ends in betrayal. At the same time, the novel features another character who fulfills the duties of the right-hand man in multiple relationships but who, in a reversal of the idiom's bodily dimensions, is literally missing his right hand: the character is of course Captain Cuttle, the emotional center of the novel. For Capuano, such a reversal is more than an uncomfortable joke; rather, by situating Cuttle as the handless but nurturing father-figure to Florence — in contrast to her able-bodied but emotionally stunted father — Dickens reconfigures the locus of success and achievement in this novel, challenging conventional ideas of (commercial) success. The ethic of care, so ably embodied in Cuttle, facilitates the happy resolution of the narrative. The "right-hand man" idiom is the clue which Capuano uses to guide us through the novel's investment in a whole nexus of interrelated ideas: "substitution and service, pride and impairment, kindheartedness and competence" (73).

Catain Cuttle consoles his friend [Phiz's illustration, fig. 5 in the book, shows the hook at the end of the Captain's extended arm].

In addition to analyzing the generative work of Dickens's idioms, the first chapter takes up two related arguments that are developed and extended in subsequent chapters. These two arguments have to do with Dickens's planning of his novels and with the question of authorial intention. Dombey was the first novel for which Dickens prepared number plans in advance (37), a practice that he was to adhere to for the rest of his career (with the notable exception of Great Expectations). For Capuano, this fact, in conjunction with Dickens's adoption of the right-hand man idiom in Dombey, suggests that the use of bodily idioms in his fiction is closely connected with the growing imaginative coherence of the later novels. Further, Capuano posits, the reliance on bodily idioms and their function as an imaginative scaffold for Dickens's novels becomes more pronounced after Dombey, culminating in the twinned idioms of Our Mutual Friend: "sweat of his brow" and "nose to the grindstone." Studying Dickens's idiom usage, then, becomes a way to think about both his development as an artist and also his creative process in any given novel--the way Dickens imagines his fictional worlds. For, according to Capuano, Dickens's use of a signature idiom in Dombey inaugurates a "standard imaginative procedure for much of his later and more sophisticated work" (37). Such an argument naturally leads us close to the idea that Dickens knew exactly what he was doing. What Dickens knew and when he knew it is not exactly the point of Capuano's idiomatic analysis, however. In certain cases, manuscripts and number plans reveal plainly what was on Dickens's mind. Capuano highlights evidence, for instance, in the manuscript of Dombey that shows Dickens testing out different modifiers to describe Carker before settling on "right-hand man" (41). Capuano also points to Dickens's adoption of the "sweat of his brow" idiom in the number plans for Our Mutual Friend (179). But the claim that Dickens was in full conscious control of his idiomatic expressions and their thematic reverberations across a given novel is very much open to question. In any case, Capuano wisely determines to leave the matter unresolved.

The remaining chapters on Bleak House, Great Expectations, and Our Mutual Friend continue to offer compelling readings of the novels starting from the signature bodily idiom and expanding out to the novel's thematic preoccupations. Capuano's analysis consistently reveals how language and theme interpenetrate, each influencing and shaping the other. The method enables us to move from Bleak House's memorable "shouldering the wheel" idiom to reflections on the work ethic (or lack thereof) that defines the trajectory of most of the novel's characters. Finally, Capuano turns to engage with the novel's ideology: the conflict between the need for personal responsibility and the desire for state action "that lies at the heart of mid-Victorian debates about liberalism" (92). In this way, the monograph shifts deftly "between the whole human horizon and the horizon of an object-glass," to borrow a phrase from a rival nineteenth-century novelist (George Eliot, Middlemarch, 640). One limitation of the method is that it can only be applied to those works with a controlling, or signature, bodily idiom; this means that Capuano is not able to include Little Dorrit (1855-57), which contains thirty unique bodily idioms (according to the corpus search data provided), but apparently not an interpretively meaningful bodily idiom. The novel's absence from the monograph undercuts the developmental dimension of Capuano's argument — the idea that in his later novels Dickens "relied more heavily (and often) on his idiomatic imagination" (175).

The Haunted Lady, or "The Ghost' in the Looking-Glass [John Tenniel's cartoon, fig. 19 in the book, reflecting on the suffering of hard-workinng seamstresses serving the idle rich].

This qualification aside, Capuano has put together a compelling analysis of the four novels he does include. The monograph represents an important contribution to discussions of Dickens's prose style, especially his ingenious and generative use of figurative language. At the same time, those interested in corpus stylistics and the novel will find here a method that effectively balances quantitative research and literary interpretation, drawing us closer to an appreciation of Dickens's linguistic imagination. While its foundation lies in digital methods, the book takes us right to the human heart of Dickens's work.

Links to Related Material

- Review of Victorian Hands: The Manual Turn in Nineteenth-Century Body Studies, ed. Peter J. Capuano & Sue Zemka

- "Shouldering the Wheel" in Dickens's Bleak House

- Sweat Work and Nose Grinding in Our Mutual Friend

Bibliography

[Book under Review] Capuano, Peter J. Dickens's Idiomatic Imagination: The Inimitable and Victorian Body Language. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2023. 281 pp. Hardback £80.39. ISBN: 9 781501 772856.

_____. Changing Hands: Industry, Evolution, and the Reconfiguration of the Victorian Body. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. London: Penguin, 1994.

Mahlberg, Michaela. Corpus Stylistics and Dickens's Fiction. New York and London: Routledge, 2013.

Stewart, Garrett. The One, Other, and Only Dickens. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018.

Created 16 February 2025