The author, with the permission of his publishers, has kindly shared with our readers the following extracts from Chapter 4 of his 2023 book, Dickens's Idiomatic Imagination: The Inimitable and Victorian Body Language. The charts appear in the book, on pp.198 and 199, and are also reproduced by kind permission; note that the references have been reformatted here. — Jacqueline Banerjee]

nlike most of his other novels, Our Mutual Friend is set in the contemporary present — as the very first words of the novel announce: "In these times of ours . . ." (13). Mary Poovey, among others, has shown how the narrator's vitriolic criticism of "these times" is connected to the ways limited liability legislation let loose "a mania for profit" where seemingly everyone inhabited "a giddy world beyond moral restraint" (51, 67). Long a proponent of the secular Victorian "Gospel of Work," Dickens began to heighten his disdain for a culture wherein financial success and social position could be achieved without ever really "working" — as the narrator says in Our Mutual Friend — but by speculating in the "mysterious business [of "Shares"] between London and Paris" that "never originated anything, never produced anything" (118). Paradoxically but pertinently, while financial speculators were enriching themselves without actually working or producing anything, Dickens was "having to buckle-to and work [his] hardest" to keep up with the incessant regimes of punishing labor on multiple fronts that he had established for himself by this point in his career (House ix: 322). Henry James was probably not far off as he famously observed that Dickens was working to "exhaustion" in Our Mutual Friend, laboring (ineffectively in James's opinion) to "d[i]g out" the novel "with a spade and pickaxe" (786).

Considering all of these juxtapositions between London's financially speculating nouveau riche and Dickens's laborious contemporary circumstances, it should be unsurprising (though no critic has yet pointed it out) that Dickens invokes different variants of the idiomatic expression derived from the primeval curse pronounced on the labor of mankind — "by the sweat of the brow shalt thou eat bread" — twenty-four times in Our Mutual Friend — and as we have seen with Dickens's other imaginatively governing body idioms, only in Our Mutual Friend among all of his other fictional works. This would seemingly confirm Robert Douglas-Fairhurst's belief that Dickens reserved his strongest mockery for the ideas to which he was most strongly attached (315). A lack of sincerity in and dedication to work was always anathema to Dickens, but it was especially so at this juncture in his life when he was pushing himself to labor on through significant pain and exhaustion. Thus, we will now consider the ways that Dickens brings what could be called idiomatic mockery to new heights in hisfinal novel — how he cultivates, hones, and nearly perfects his growing penchant for exploiting an idiom's malleability by way of its direct applications and violations. I agree, in this sense, with Garrett Stewart who has recently seen Our Mutual Friend, contra Henry James and other contemporary reviewers, less as "a depletion of genius than its [genius's] compendium" wherein Dickens's career-long "phrasal habits [become] etched into a sharper new outline." (277). For Stewart Our Mutual Friend is the novel where Dickens's "ingrained verbal flourishes" solidify into a "stylistic summa" as the Inimitable's "lexicon gets emphatically repackaged, [and] labelled with the rhetorical equivalent of 'registered trademark'" (227, 240). The "stylistic summa" of his career-long phrasal habits, the ultimate "registered trademark" we encounter in Dickens's final novel, in my view, though, is distinctly — and doubly — idiomatic.

I say this because the idiomatic intensification Dickens achieves in his last novel involves his imaginative orchestration of not just one but two principal body idioms. We will see how nineteen variants of a second idiom used only in Our Mutual Friend and in no other novel — "nose to the grindstone" — links up with the former, first as an expression describing one hard at work and then eventually in terms of the idiom's wider association with coercion, deception, and social mastery. As we have seen, this use and misuse' of idiomatic body language has been an accretive and an imaginatively embodied process for Dickens in his mature fiction: the right-hand men and women in Dombey, the characters with and without actual shoulders to put to the wheel in Bleak House, the nurturing and neglecting ways of being brought up by hand in Great Expectations (Bodenheimer 36; Bodenheimer contends that Dickens's "central subject was the use and misuse of language." I agree but argue that his central subject is more precisely a use and misuse of idiomatic body language.). Now we encounter at the end of Dickens's career a showcase of characters who do and do not work "by the sweat of their brows," who do and do not put theirs and others' "noses to the grindstone." Tracing how these unique idioms* emerge — and eventually merge — will allow us a new and privileged glimpse into how Dickens imagined the novel that many, such as [U.C.] Knoepflmacher (137), and [Adrian] Poole (xxii) consider his most self-consciously constructed work. We will see Dickens fulfilling Mikhail Bakhtin's hypothetical case where "parodic stylizations" of social dialects may "be drawn in by the novelist for the orchestration of his themes and for the refracted (indirect) expression of his intentions and values" (292).

The evaluation of the ways in which these two idioms come to structure Our Mutual Friend rhetorically and thematically, however, involves a careful analysis of their appearances over the course of the first five numbers (May through September 1864 installments) as well as an examination of what is known about the novel's provenance once Great Expectations drew to a close. I mention the first five numbers for a specific reason. Dickens's composition of Our Mutual Friend involved a planned return to the monthly number format after almost a decade of writing fiction for weekly publication (Hard Times, A Tale of Two Cities, Great Expectations). As Sean Grass has shown (45), this return to an elongated publication setup, combined with failing health, the mishandled (and very public) dissolution of his marriage, a concealed new relationship with Ellen Ternan, and declining reputation among contemporary critics, prompted Dickens to make a resolution to Forster that he would not to begin publishing his new long novel with fewer than five numbers completed in advance. Earlier in his career, Dickens had written overlapping novels (Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge) without any sizable written backlog. However, with his final few novels, he had increasingly wanted a substantial reserve in place before publication began. Partly owing to the complexity of his later art and the difficulty of proceeding rapidly with it while juggling so many other demands on his time but also because a comfortable reserve of writing was now a necessary hedge against illness, distress, and unforeseen interruptions, Dickens conceded to Forster that he was "forced to take more care than [he] once took" (Stone 331). My overarching argument is that as Dickens took more care in composing his later novels, he also relied more heavily (and often) on his idiomatic imagination to help him organize and execute his novels' plot formulations, characterizations, and themes. Based on what we know about Great Expectations' success, the content of early planning documents for Our Mutual Friend, and speed and assurance with which he eventually wrote the novel's early sections in late 1863 and early 1864, it is entirely possible that Dickens — after struggling mightily to organize what he called the leading "notions" of his new book — returned from his fortnight in France with relatively definitive ideas of how these two idiomatic phrases, "by the sweat of the brow" and "nose to the grindstone," could productively inform Our Mutual Friend's twenty numbers. [173-75]

_____________

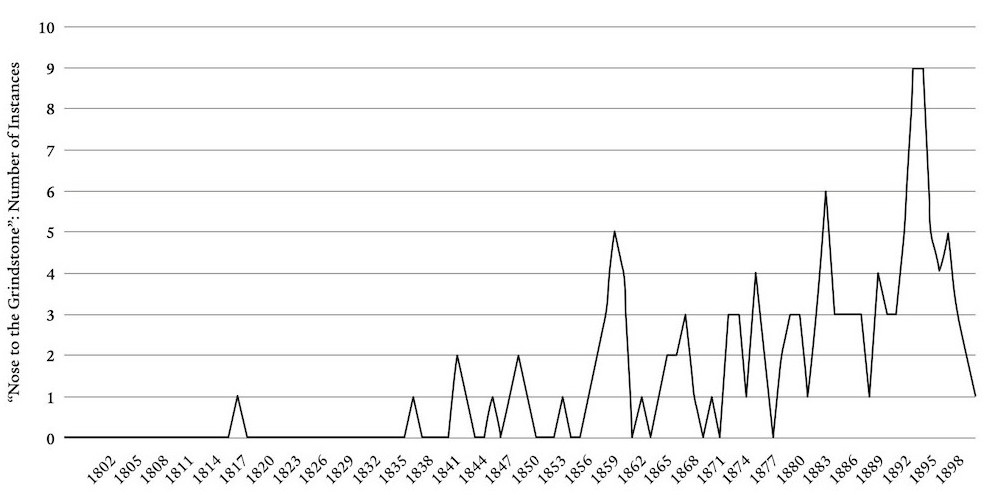

*These body idioms were not just unique in Dickens's oeuvre; they were extremely rare in nineteenth-century novels more generally: the "sweat of the/my brow" idiom is used three times in one novel, twice in four novels, and a single time in forty-five other novels in my corpus of more than 3,700 nineteenth-century novels. The "nose to the grindstone" idiom is even more rare. [See instances in two archives:]

>

>

Chart showing number of instances of "nose to the grindstone"in the British Library Newspapers Digital Archive

Chart showing the number of instances of "nose to the grindstone" in the British Periodicals archive.

Dickens invokes it or its variants nineteen times in Our Mutual Friend while it appears only thirteen times (all single instances) in the 3,700-novel corpus. [174, n. 3]

Links to Related Material

- The Story of Dickens's Last Complete Novel — a review of Sean Grass's Charles Dickens's "Our Mutual Friend": A Publishing History (2014)

- "Shouldering the Wheel" in Dickens's Bleak House

Bibliography

[Source of extracts] Capuano, Peter J. Dickens's Idiomatic Imagination: The Inimitable and Victorian Body Language . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2023 [Review].

Bakhtin, Mikhail. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981.

Bodenheimer, Rosemarie. Knowing Dickens. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univeristy Press, 2007.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. 1864-65. New York: Penguin, 1997.

Douglas-Fairhurst, Robert. Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Grass, Sean. Charles Dickens's "Our Mutual Friend": A Publishing Hisotry. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014 [Review].

James, Henry. "Our Mutual Friend." The Nation. 21 December 1865. 786-87.

House, Madeline, Grahma Storey, Kathleen Tillotson, and Margaret Brown, eds. The Letters of Charles Dickens. 12 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965-2002.

Knoepflmacher, U.C. Laughter and Despair: Readings in Ten Novels of the Victorian Era. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971.

Poole, Adrian. Introduction to Our Mutual Friend. New York: Penguin, 1997: ix-xxiv.

Poovey, Mary. "Reading History in Literature: Speculation and Virtue in Our Mutual Frioend." In Historical Criticism and the Challenge of Theory. Edited by Janet Levarie-Smarr. Urbana -Champaign: Unoversity of Illinois Press, 1993. 42-80.

Stewart, Garrett. "The Late Great Dickens: Style Distilled." In On Style in Victorian Fiction, edited by Daniel Tyler. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. 227-43.

Stone, Harry. Dickens' Working Notes for His Novels. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Created 13 February 2025