“My other piece of advice, Copperfield," said Mr. Micawber, "you know. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen nineteen six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds nought and six, result misery. The blossom is blighted, the leaf is withered, the god of day goes down upon the dreary scene....” — Mr Micawber in David Copperfield (Ch. 12)

Dickens as a debtor's son

harles Dickens's personal experience of debtors' prisons is well known. His father, John, worked as a clerk in the naval pay offices at Portsmouth, Chatham, and London. Profligate by nature, he never had much of a head for business, and, besides, was maintaining a family of eight on four shillings a week. In 1824 he found himself imprisoned for debt. His wife and all but one of his children joined him in the Marshalsea debtors' prison. The exception was twelve-year-old Charles, who was put to work at Warren's Blacking Factory, some twelve miles away, at Hungerford Stairs by the Thames. All this is familiar to us because biographer John Forster has made available to us Dickens's personal and very painful recollections of his father's arrest and imprisonment in an autobiographical fragment, recollections which are also reflected in "Where We Stopped Growing" (Household Words, 1 January 1853).

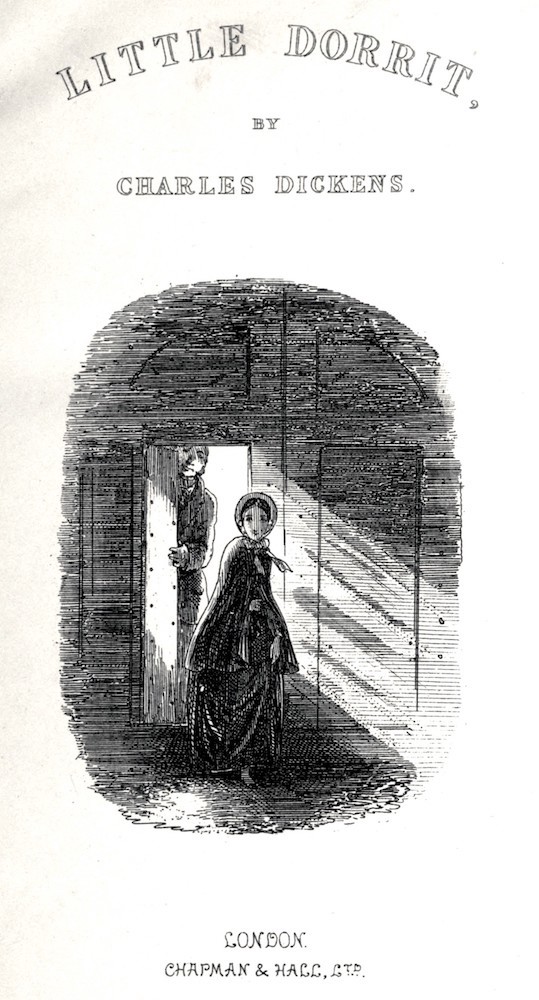

Hablot Knight Browne's depiction of the Marshalsea's

main

entrance in Little Dorrit: Little Dorrit leaving The

Marshalsea, title-page and

vignette (June 1857).

John Dickens was fortunate enough to inherit £450 upon his mother’s death, which he could apply to the settlement of his debts. After a matter of merely fourteen weeks' incarceration in the Marshalsea, and following a hearing before a panel of judges accounting for his debts in Rochester and London, he was released on 28 May 1824. However, that November and again in November 1825 he had to hand over to his debt trustee considerable sums.

The revelations of Dickens's painful childhood experiences, before his rise to international fame in his twenties, gave him a life story that critics have found as riveting as Dickens’s fiction itself. But they were not just the background to a brilliant career. The damage to his psyche was not so easily repaired. He never quite escaped the taint of the debtors' prison. This may well have contributed to his determination from an early age to be a financial success, and not fall into his father's error of spending beyond his means. Moreover, he would return to this experience again in Wackford Squeers (ultimately) in Nicholas Nickleby to Wilkins Micawber (temporarily) in David Copperfield.

Debtors in the early nineteenth century

The experience was not an unusual one. At that time perhaps as many as 10,000 debtors were imprisoned annually. Indeed, in his biography of Dickens, Peter Ackroyd finds a much higher estimate for the year 1837, when there were apparently between 30,000 and 40,000 arrests for debt throughout the United Kingdom (47). These unfortunates were kept in incarceration until they could completely discharge their obligations under the Insolvent Debtors' Act. So a prison term did not erase a person's debt; in fact, the inmate of an establishment such as the Marshalsea was required to repay the creditor in full before he or she would be discharged, paying, in addition to that, the cost of his incarceration. It could be almost impossible to gain release. Ironically, the system dealt for the most part with relatively small debts; in 1827, for example, 414 out of the Marshalsea's 630 inmates were incarcerated for debts under twenty pounds each, often incurred with tradespeople (see Wade 124).

Life in the Marshalsea

From Dickens's novels one can derive a fairly accurate sense of both the layout and the atmosphere of the Marshalsea. Those who entered it from the main Southwark thoroughfare (the Borough High Street) would pass by the turnkey's lodge and, through Angel Court, enter a small yard in front of the main cellblock. Each cell measured eight feet by twelve feet, and contained a fireplace, cupboard, and small, barred window which afforded a glimpse of the sky above the rooftops but not the street. The Marshalsea had a central exercise yard, in which the Dorrit brothers are shown taking the air, and a taproom, a common recreational room in which the inmates (if they could afford to do so) might drink beer and ale. Ackroyd succinctly describes the tightly confined space between high brick walls as "crowded, noisy, squalid and malodorous; a dank and desperate reality" (71). At ten in the evening the ringing of the institutional bell was the signal for the departure of all non-inmates as the gates would be locked for the night. In a notable incident in Little Dorrit, the heroine, Amy, finds herself locked out.

"Within the Rules"

Hablot Knight Browne's depiction of debtor Walter Bray in

his

rented flat in Dickens's Nicholas Nickleby (June 1839).

Not all prisoners were incarcerated, though. In England and Wales, debtors' prisons varied in the amount of personal freedom they would permit their inmates. Some prisons allowed inmates to conduct business and even to receive visitors; moreover, others such as the King's Bench Prison would even permit an inmate (such as Walter Bray in Nicholas Nickleby) to live a short distance beyond the confines of the prison itself – hence, Dickens mentions Nicholas's visiting Walter Bray and Madeline in a private, second-storey apartment "within the 'Rules'" of the King's Bench Prison.

The Marshalsea, the Fleet, and debtors in the novels

Drawing on his considerable and unhappy experience of the Marshalsea, Dickens makes his most telling allusions to debtors' prisons in The Pickwick Papers (1836), David Copperfield (1849), and Little Dorrit (1857).

The first prison that Dickens borrowed as a developed backdrop for the action of his fiction was the Fleet, which occurs in many of Pickwick's most memorable scenes and is captured in the picaresque novel's illustrations (see below). Here, in the central court, the inmates would slink about, lounging and whiling away the day, "with as little spirit or purpose as the beasts in a menagerie" (Ch. 45). Dickens was drawn to comment on the conditions of such places not simply because of his personal experiences, but because, as his interest in orphanages, Ragged Schools and other institutions shows, he took on the role of social crusader. As for prisons in general, he features conventional prisons such as that at Marseilles (Little Dorrit), the Conciergerie (A Tale of Two Cities), the Bastille (A Tale of Two Cities), and the Abbaye (A Tale of Two Cities). But the physical and psychological conditions of convicted debtors were a special preoccupation, and the prisons in which they were confined appear in several novels: the Fleet (in Pickwick Papers, Chapters 41-47) and the King's Bench (David Copperfield, Chapter 11; also in (Nicholas Nickleby, Chapter 46). For example, Dickens confines the ever-optimistic Wilkins Macawber in David Copperfield not to the low-ceilinged, foul-smelling Marshalsea to which John Dickens, his wife Elizabeth and three children were consigned, but to the more commodious King’s Bench Prison.

Dickens and prison reform

Throughout his travels on the Continent and in America Dickens visited prisons, and recorded his impressions with a reformer's eye. He had read extensively about prisons and the necessity for prison reform, and this background is reflected in his handling of the Newgate scenes in Oliver Twist. For example, the illustrator, George Cruikshank, provides a telling visual realisation of Fagin's last night alive in the condemned cell (March 1839). However, again and again Dickens returns to the issue of imprisonment for debt. George Heyling in the inset tale in Pickwick Papers, Chapter 21, and William Dorrit in the second chapter of that later novel onwards, as well as Walter Bray in Nicholas Nickleby, Chapter 46 onwards, are three notable examples of how incarceration for debt in places such as the Marshalsea could break a man's spirit and warp his character. Since only a miraculous inheritance such as came John Dickens's way could effect the debtor's release, such people were likely to wander the corridors and courts of such places as the Marshalsea, the Fleet, and the King's Bench Prison for the remainder of their lives.

The fate of the Marshalsea

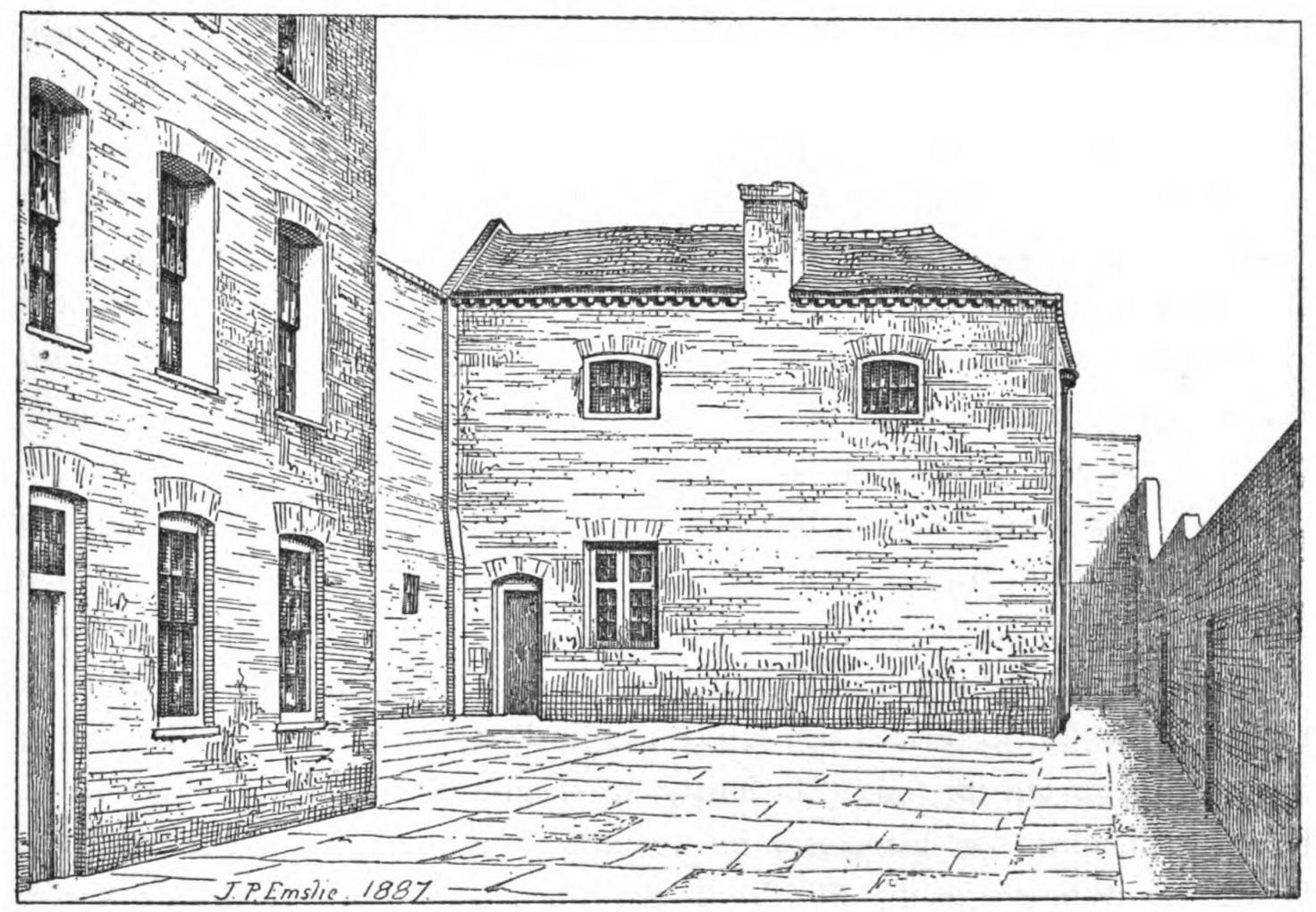

What remained of the Marshalsea in 1887 (Plate IV

of J. P. Emslie's topographical record of London)

The building that Dickens knew as a child was actually the second building on the site, the original fourteenth-century building having been demolished and replaced in 1811 with a building in two sections or wings: one for Admiralty prisoners awaiting court martial, and the other for constrained debtors. This second prison survived intact for just 38 years. On Wednesday, 6 May 1857, after the Marshalsea had been demolished, Dickens, forty-five-years old, visited the site. As Ackroyd notes, "until recent years, there was a plaque upon part of the old wall which read: 'This site was originally the MARSHALSEA PRISON made famous by the late Charles Dickens in his well know work 'Little Dorrit'" (779). After the 1870s little of the for-profit, private prison remained, except for the high wall that had originally surrounded the buildings to the south; a local public library for the Borough of Southwark now stands on the site.

Related Material

Five Plates from Pickwick (by Phiz), 1836-37:

- The Last Visit of Heyling to the Old Man (November 1836)

- Mr. Pickwick sits for his Portrait (May 1837)

- The Warden's Room (July 1837)

- The Discovery of Jingle in the Fleet (August 1837)

- Mrs. Bardell encounters Mr. Pickwick in the Prison (August 1837)

Two plates from Sketches by Boz (Cruikshank), 1836-39:

- The Broker's Man (1836)

- The Lock-up House in "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle" (1839)

One plate from David Copperfield (Phiz), 1849-50:

- I am shewn two interesting penitents (Nov., 1850)

Five plates from Little Dorrit (Phiz), 1855-57:

- Little Dorrit leaving the Marshalsea (June 1857)

- Detail of Little Dorrit leaving the Marshalsea (June 1857)

- The Brothers in the Yard of the Marshalsea (May 1856)

- The Pensioner Entertainment (9 August 1856)

- The Marshalsea becomes an Orphan (October 1856)

- In the Old Room (May 1857)

James Mahoney's Household Edition illustration of Arthur Clennam in the Marshalsea:

Topics:

- Dickens: A Brief Biography

- Nineteenth-Century Britain: A Nation of Debtors

- Prisons in Little Dorrit

- Material Culture as Society Informant: Prisons in Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. Illustrated by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1839.

Illustrated topographical record of London. Changes and demolitions, 1880-[1890] ... [Being drawings by J. P. Emslie, with comments by the artist, and historical notes by Philip Norman], series 2. Plate 4. Hathi Trust. Contributed by the University of Michigan. Web. 9 September 2021.

Litvack, Leon. "Prisons and Penal Transportation." Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Ed. Paul Schlicke. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999. Pp. 465-467.

Wade, John. A Treatise on the Police and Crimes of the Metropolis..... London: Longman, Rees etc., 1829. Google Books. Free Ebook.

Created 9 September 2021