Like Edgeworth’s Harrington and Grace Aguilar’s The Vale of Cedars, Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s historical novel, Leila, or the Siege of Granada, throws considerable light on the representations of Jews in the literature of the early decades of the nineteenth century. Elected to Parliament as both a Liberal. (1831-1841) and a Tory (1851), Bulwer-Lytton was also a prolific novelist and a friend of both Isaac D’Israeli and his son Benjamin Disraeli. Since Leila, is now little known, our account of it will be more detailed and descriptive than would otherwise be called for.

Left: Leila’s title-page. Middle: Leila. Right: The Last Battle of the Moors. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Like Aguilar’s Grove of Cedars, Leila takes place in the time of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain. (Aguilar actually wrote her novel several years before Leila appeared, but it was published later.) Leila, which presents Torquemada’s vision of the Jews in all its ugly hatefulness, has a principal Jewish character, the “enchanter” Almamen, side first with the Moors against the Christians, then with the Christians against the Moors, and finally with Moors against the Christians. He devotes his life to a single overriding cause — the preservation of the Jews, even at the cost of his beloved daughter Leila. He has raised her in isolation, keeping her from all outside influence, even that of other, possibly insufficiently pious Jews. He does this so that she can somehow preserve the line of Israel until the appearance of its saviour. In fact, his plan mirrors, even parodies, the way Christians and their Tree of Jesse established a line of descent for Jesus that demonstrated his essential, fundamental royalty.

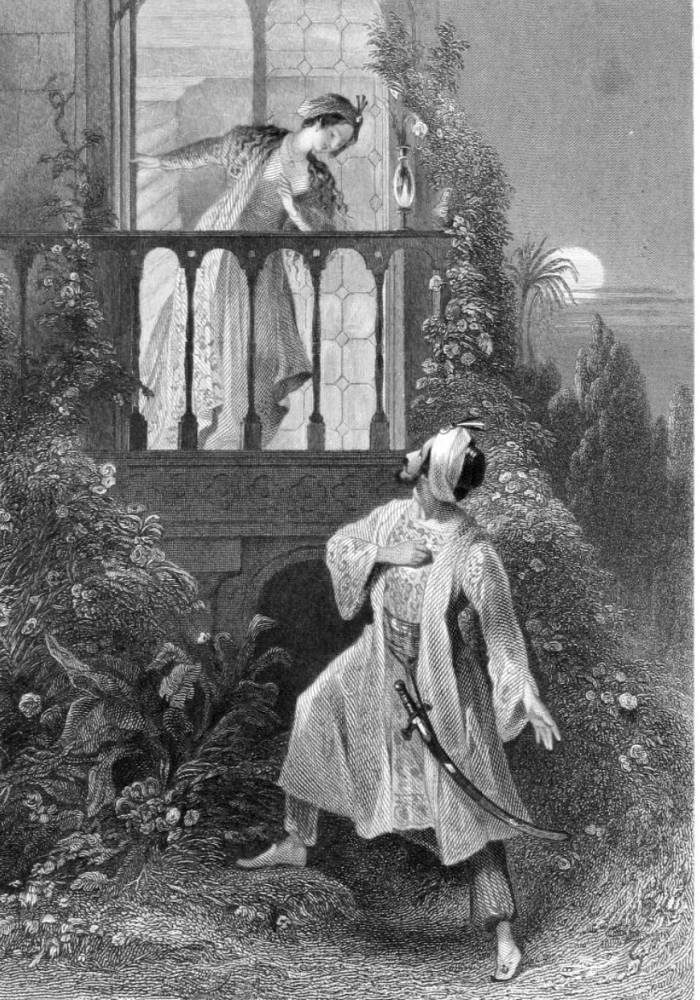

Encountering Bulwer-Lytton’s description of her fairy-tale like isolation, the reader is not surprised when, like Rapunzel, she is found by a King’s son who falls in love with her. Muza, the son of the Moorish king of Granada, scales high walls and falls in love with her. Disregarding his religion, she cannot answer Muza’s repeated inquiries about her identity. “I know nothing of my birth or childish fortunes, save a dim memory of a more distant and burning clime; where, amidst sands and wastes, springs the everlasting cedar, and the camel grazes on stunted herbage withering in the fiery air!’ She dimly remembers her mother whose “soft songs hushed me into sleep” but she has “passed from childhood into youth within these walls. . . and those who have seen both state and poverty, which I have not, tell me that treasures and splendour, that might glad a monarch, are prodigalised around me.” She knows nothing of her family, but, as she tells Muza, “my father, a stern and silent man, visits me but rarely—sometimes months pass, and I see him not." In fact, she doesn’t even know his name. Ximen, the “chief of the slaves” who take care of her, has told her that if her father learns of her visitor, “you will have looked your last upon Granada. Learn,' he added, (in a softer voice, as he saw me tremble,) 'that permission were easier given to thee to wed the wild tiger, than to mate with the loftiest noble of Morisca! Beware!” (18-19)

After Almamen’s move to the Christian side, from which he hopes to achieve more for the Jews, Leila finds herself in “one of a long line of tents, that skirted the pavilion of [Queen] Isabel.” Dejected and fearful, she hears “the deep and musical chime of a bell summoning the chiefs of the army to prayer” -- for Ferdinand, the narrator observes, “invested all his worldly schemes with a religious covering, and to his politic war he sought to give the imposing character of a sacred crusade.” In this he was assisted by the Grand Inquisitor Torquemada. Recognizing in the sound of the bell the call to prayer of the “Nazarenes,” Leila sees herself as a “captive by the waters of Babylon,” and “sinking to her knees,” pleads with God to “succour and defend me, Thou who didst look of old upon Ruth standing amidst the corn, and didst watch over thy chosen people in the hungry wilderness, and in the stranger's land."

Left: The Miracle title-page. Middle: The Favourite Slave. Right: Amine at the feet of Boabdil. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

At this point in the story Leila encounters the libertine Don Juan, heir to the Spanish throne, who tries to seduce her, promising, “Be but mine, and no matter, whether heretic or infidel, or whatever the priests style thee, neither church nor king shall tear thee from the bosom of thy lover." Still faithful to Muza, Leila is terrified, but matters become even worse when Torquemada, the villain of the novel, overhears the prince and intervenes, reminding him that a good Christian hates and distrusts all infidel Jews. The Dominican Tomas de Torquemada assures the libertine that his attempts to seduce the young girl are not his fault: ‘Prince,’ said the friar, after a pause, ‘not to thee will our holy church attribute this crime; thy pious heart hath been betrayed by sorcery. Retire.’" In other words, according to the priest, the Jew Almamen has used his sorcery to create, for his own nefarious purposes, the Christian prince’s attraction to the Jewish girl. Torquemada then turns his attention to Leila, inquiring about her religion and that of her father. The ignorant girl knows only that “he disowns, he scorns, he abhors, the Moorish faith” believing in “the one God, who protects his chosen, and shall avenge their wrongs — the God who made earth and heaven; and who, in an idolatrous and benighted world, transmitted the knowledge of Himself and his holy laws, from age to age, through the channel of one solitary people, in the plains of Palestine, and by the waters of the Hebron."

With that information in hand, Torquemada leaves her with a smile — “a smile in which glazing eyes and agonising hearts had often beheld the ghastly omen of the torture and the stake.” He seeks King Ferdinand to whom he offers a source of desperately needed funds to finance a war that will drive the Moors from Spain. Other Christian kings, “avaricious and envious,” have refused to finance such a religious war, but the friar points out that the royal couple can simply take money from Jews, “men of enormous wealth” which “they have plundered from Christian hands, and consume in the furtherance of their iniquity. Sire, I speak of the race that crucified the Lord.” When King Ferdinand demurs, “The Jews — ay, but the excuse?” Torquemada responds by pointing to Almamen’s siding with the Moors.

And has he not left with thee, upon false pretences, a harlot of his faith, who, by sorcery and the help of the Evil One, hath seduced into frantic passion the heart of the heir of the most Christian king? . . . The arts that seduced Solomon are employed against thy son . . . so that, through the future sovereign of Spain, the counsels of Jewish craft may establish the domination of Jewish ambition. How knowest thou . . . but what the next step might have been thy secret assassination, so that the victim of witchcraft, the minion of the Jewess, might reign in the stead of the mighty and unconquerable Ferdinand?"

Like Aguilar, Bulwer-Lytton makes Torquemada and the Catholic Church entirely responsible for the persecution of the Jews rather than the reigning sovereigns, Ferdinand and Isabella, both of whom are shown to have misgivings. Having acceded in principle to the Inquisitor’s demands, the king is uneasy and seeks “the solace of confession.” What he confesses to, however, are minor omissions in his religious practice. He cannot bring himself to acknowledge that “he persecuted from policy,” but instead “believed, in his own heart, that he punished but from piety.” Neither the prince nor the monk, as the narrator takes care to point out, could imagine that there was “an error to confess in, or a penance to be adjudged to the cruelty that tortured a fellow-being, or the avarice that sought pretences for the extortion of a whole people” (81-83).

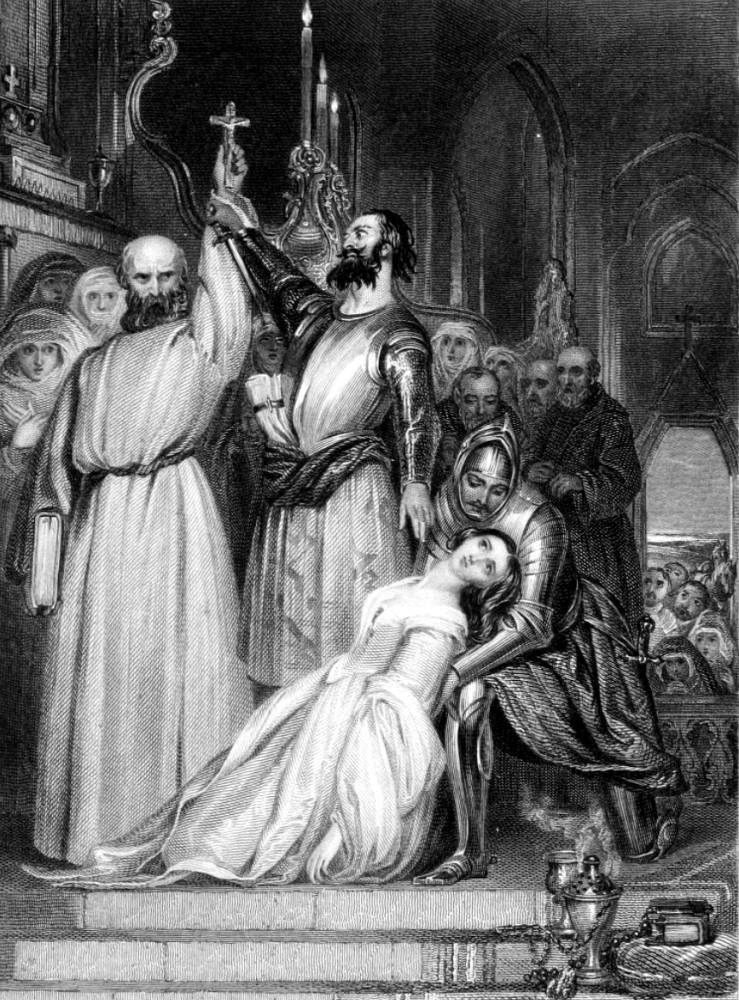

Left: Muza at the Lattice of Leila title-page. Right: The Death of Leila.

Again like Aguilar, Bulwer-Lytton imagines the development of a mutual affection, a loving mother-daughter relationship, between Queen Isabella and the young Jewish girl left behind in the Christian camp after her father defected to the Moors. Isabella’s kindness and compassion, seconded by that of the motherly woman to whom the queen entrusts her, lead Leila to form a more positive view of Christianity and to recognize that her own feelings are not in any way un-Christian. Quite the contrary. The Jewess will be redeemed, the reader can anticipate, by converting of her own free will, as Isabella had hoped and planned, to the true religion.

Transferred, at Isabella’s command, to a large fortress, Leila finds herself in the company of a kind and thoughtful older woman, the Donna Inez de Quexada, “the only lady in Spain, of pure and Christian blood, who did not despise or execrate the name of Leila's tribe. Donna Inez had herself contracted to a Jew a debt of gratitude which she had sought to return to the whole race.” As she herself explains to Leila, her son had been twice saved from dangerous robbers by a Jew, with whom the young man became a close friend. On her son’s deathbed, he had made his mother swear that she would not share the general prejudice against Jews but help them as best she could. Later the narrative reveals that her son’s Jewish saviour was none other than the youthful Almamen — still “dignified and stately” at the time, according to Donna Inez, and bearing “no likeness to the cringing servility of his brethren” (96, 119-20) — in other words, not like other Jews! This episode convinces the reader that Leila’s father was generous and humanitarian before Spanish Christians’ hatred of Jews transformed him into a scheming fanatic.

The novel progresses through episode after lively episode in the political and military struggle for Granada between Christians under Ferdinand and Isabella, and Moors under Boabdil (Muhammed XII). Leila’s father, who has somehow managed to slip behind the Christian lines to visit her, warns her never to abandon her commitment to her fellow Jews. She is nonetheless drawn to Christianity, having come to see it as the fulfilment of Judaism: “Often she . . . startled the worthy Inez, by exclaiming, ‘This, your belief, is the same as mine, . . . — Christianity is but the Revelation of Judaism” (100). In this conviction, she converts and resolves to end her days as a nun in a convent, but before she can take her vows a trio of men try to dissuade her: Learning of her conversion, Almamen reaches the convent where his daughter is to take vows accompanied by Muza, the Moorish prince. They are preceded by Don Juan, now magically transformed from a libertine into a true lover, who pleads passionately with Leila not to cut herself off from the joys of the world but to join him in a loving and protective union. Touched by his appeal, which reminds her of her love for Muza, Leila confesses that another had already won her heart.

"Prince, I trust I have done with the world, and bitter the pang I feel when you call me back to it. But you merit my candour: I have loved another; and in that thought, as in an urn, lie the ashes of all affection. That other is of a different faith. We may never — never meet again below, but it is a solace to pray that we may meet above. That solace, and these cloisters, are dearer to me than all the pomp, all the pleasures, of the world. Go, then, Prince of Spain, son of the noble Isabel, Leila is not unworthy of her cares. Go, and pursue the great destinies that await you. And if you forgive — if you still cherish a thought of — the poor Jewish maiden, soften, alleviate, mitigate the wretched and desperate doom that awaits the fallen race she has abandoned for thy creed." Invoking a blessing on her, the prince withdraws in sadness. “‘I thank thee, Heaven, that it was not Muza!’" Leila mutters, “breaking from a reverie, in which she seemed to be communing with her own soul; ‘I feel that I could not have resisted him.’ With that thought she knelt down, in humble and penitent self-reproach, and prayed for strength. Her warmest wish now, was to abridge the period of her noviciate, which, at her desire, the church had already rendered merely a nominal probation.”

Soon after, Almamen appears on the scene, mounted behind Muza on the latter’s horse after an exhausting and dangerous ride behind the Christian lines. About an hour into their journey, Almamen had paused.

“I am wearied,” said he, faintly; “and, though time presses, I fear that my strength will fail me.” “Mount, then, behind me,” returned the Moor, after some natural hesitation: “Jew though thou art, I will brave the contamination for the sake of Leila.” “Moor!” cried the Hebrew, fiercely, “the contamination would be mine. Things of the yesterday, as thy prophet and thy creed are, thou canst not sound the unfathomable loathing, which each heart, faithful to the Ancient of Days, feels for such as thou and thine" (174).

The relations of Jews and Moslems are clearly hardly any better than those of Jews and Christians.

The scene of the arrival of Almamen at the convent, the highpoint of the novel, deserves to be quoted at some length. The men first catch sight of the convent from a distance.

On a gentle eminence, above this plain or garden, rose the spires of a convent; and, though it was still clear daylight, the long and pointed lattices were illumined within; and, as the horsemen cast their eyes upon the pile, the sound of the holy chorus — made more sweet and solemn from its own indistinctness, from the quiet of the hour, from the sudden and sequestered loveliness of that spot, suiting so well the ideal calm of the conventual life — rolled its music through the odorous and lucent air.

The Christian music, which the Muslim prince and Jewish plotter hear from a distance, rouses Almamen “into agony and passion” upon which “he smote his breast with his clenched hand; and, shrieking, rather than exclaiming, ‘God of my fathers! have I come too late?’ buried his spurs up to the rowels in the sides of his panting steed. Along the sward, through the fragrant shrubs, athwart the pebbly and shallow torrent, up the ascent to the convent, sped the Israelite.” Muza, “wondering and half reluctant, followed at a little distance,” and encountering a “small group of the peasants,” he learns, "A nun is about to take the vows." Rushing into the chapel, he sees tragedy about to unfold.

Round the consecrated rail flocked the spectators, breathless and amazed. Conspicuous above the rest, on the elevation of the holy place, stood Almamen, with his drawn dagger in his right hand, his left arm clasped around the form of a novice, whose dress, not yet replaced by the serge, bespoke her the sister fated to the veil: and, on the opposite side of that sister, one hand on her shoulder, the other rearing on high the sacred crucifix, stood a stern, calm, commanding form, in the white robes of the Dominican order: it was Tomas de Torquemada. "Avaunt, Abaddon [Prince of Darkness]!" were the first words which reached Muza's ear, as he stood, unnoticed, in the middle of the aisle: "here thy sorcery and thine arts cannot avail thee. Release the devoted one of God!" "She is mine! she is my daughter! I claim her from thee as a father, in the name of the great Sire of Man!"

Torquemada cries, “‘Seize the sorcerer! seize him!’ . . .But not a foot stirred — not a hand was raised. The epithet bestowed on the intruder had only breathed a supernatural terror into the audience; and they would have sooner rushed upon a tiger in his lair, than on the lifted dagger and savage aspect of that grim stranger.” At this point Leila seals her fate when she declares that she has become a Christian: “‘Oh, my father!’ then said a low and faltering voice, that startled Muza as a voice from the grave — ‘wrestle not against the decrees of Heaven. Thy daughter is not compelled to her solemn choice. Humbly, but devotedly, a convert to the Christian creed, her only wish on earth is to take the consecrated and eternal vow.’" Almamen, realizing his plan to save Jews has failed, cries out, “The veil is rent — the spirit hath left the temple. Thy beauty is desecrated; thy form is but unhallowed clay” and stabs his daughter three times and then escapes. (177-80).

Leila’s fate confirms the generally held view among Bulwer-Lytton’s Christian readers, that Jewish women were more sensitive and more susceptible to the appeal of Christianity, more open to conversion, than Jewish men. Unlike Scott’s Rebecca or Aguilar’s Marie, both of whom, without being fanatically committed, remain deeply loyal to their Jewish faith, Leila willingly converts to Christianity. Indeed, her martyrdom at the hands of her own father transforms her into a Christ-figure, rejected and crucified by her own people: At the same time, the novel implies that as long as persecution and extortion of the Jews continue, so too, on their side, will disloyalty, dissimulation, and fanaticism, extending to violence and even, in an extreme case, to infanticide.

Bulwer-Lytton nevertheless cautiously and uncertainly evokes the possibility of some form of coexistence and mutual respect. As a young man, Almamen, as we saw, was not a fanatic but a generous human being eager to help out an endangered fellow human being, who happened to be a Christian. He happily became the young man’s friend. More guardedly, at the end of their bloody conflict Bulwer-Lytton depicts the enemies, Ferdinand, Isabella, and Boabdil -- the victorious Christians and the defeated Moor – parting on a note of limited mutual respect. The victorious Spaniards impose relatively moderate peace conditions on their defeated enemy, even though they have not overcome their profound religious and political estrangement. When Ferdinard graciously refuses to allow Boabdil to dismount and offer obeisance of the conquered to the conqueror, he tells him, "Brother and prince . . . forget thy sorrows; and may our friendship hereafter console thee for reverses, against which thou hast contended as a hero and a king—resisting man, but resigned at length to God!" The prince thereupon has his men present the keys of the city to Ferdinand. "O king!" he says. "Accept the keys of the last hold which has resisted the arms of Spain! The empire of the Moslem is no more. Thine are the city and the people of Granada: yielding to thy prowess, they yet confide in thy mercy." With the Spaniard’s response, the novel closes:

“Since we know the gallantry of Moorish cavaliers, not to us, but to gentler hands, shall the keys of Granada be surrendered.” Thus saying, Ferdinand gave the keys to Isabel, who would have addressed some soothing flatteries to Boabdil: but the emotion and excitement were too much for her compassionate heart, heroine and queen though she was; and, when she lifted her eyes upon the calm and pale features of the fallen monarch, the tears gushed from them irresistibly, and her voice died in murmurs. . . .There was a momentary pause of embarrassment, which the Moor was the first to break. "Fair queen," said he, with mournful and pathetic dignity, "thou canst read the heart that thy generous sympathy touches and subdues: this is thy last, not least, glorious conquest. But I detain ye: let not my aspect cloud your triumph. Suffer me to say farewell.” (194-96)

Related material

- The History of Jews in Great Britain

- The Acculturation of British Jews and Their Participation in English Literary Culture

- The Depiction of Jews in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century English Literature

Bibliography

Bulwer-Lytton, Edward. Leila, or the Siege of Granada. Paris: A. and W. Galignani, 1838. Original edition, London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1838.

Crome, Andrew. Christian Zionism and English National Identity, 1600-1850. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Darby, Michael R. The Emergence of the Hebrew Christian Movement in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

Edgeworth, Maria. Harrington in Tales and Novels. Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1969), IX: 1-208 (rprt. of The Longford Edition, 1893)..

Goldsmid, Francis Henry. Remarks on the Civil Disabilities of British Jews. Postcript, April 1833. London: Henry Colburn and Richard Francis Bentley, 1830.

Harrison J.F.C. The Second Coming: Popular Millenarianism 1780-1850. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979.

Ragussis, Michael. Figures of Conversion: “The Jewish Question” & English National Identity. Durham: Duke University Press, 1995.

Scult, Mel. “English Missions to the Jews: Conversion in the Age of Emancipation,” Jewish Social Studies, 35 (1973):. 3-17.

Wilson, A.N. Introduction to Ivanhoe. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1986.

Last modified 9 July 2020