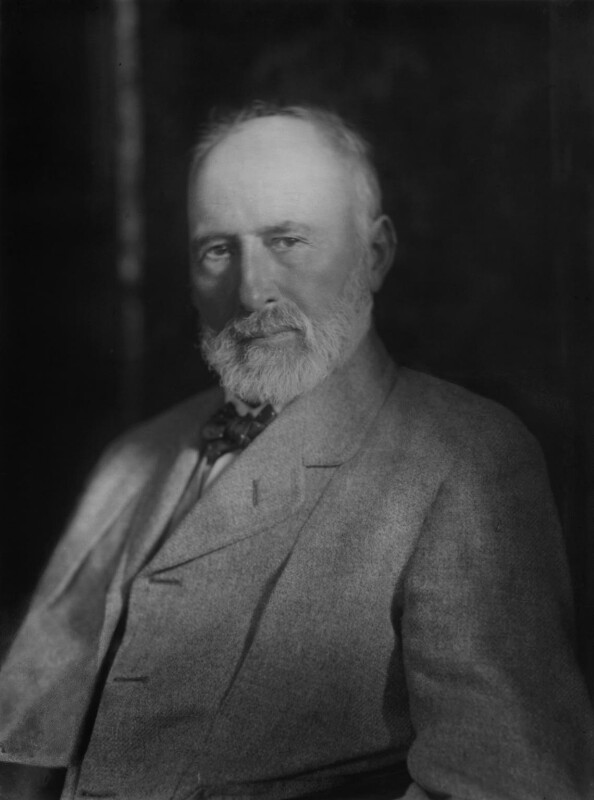

William Robinson, by Vandyk, © National

Portrait Gallery, London.

illiam Robinson (1838–1935) was a garden designer whose publications on horticulture and gardening in general were extremely influential. Beyond the basic facts that he was born in Ireland on 15 July 1838, to William and Catherine Robinson, very little is known for sure about his early life: E. Charles Nelson, author of the current entry on him in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, does not repeat earlier information about his family — for example, that his father was a land agent who absconded with his employer's wife — because there he found no firm basis for it. Robinson's later career as a writer and publisher does suggest that he was well educated, even if he left school fairly early. It is also clear that the first steps on his career were on two of Ireland's big estates: as a garden-boy at Curraghmore, the seat of the Marquess of Waterford, where his work involved carrying water from the river to the glasshouses, then as a gardener at Ballykilcavan, near Stradbally, in Queen's County (now known as County Laois), where he became a foreman gardener.

With this stock of experience, the ambitious young Irishman travelled to London. He must have acquitted himself well so far, because he took with him a letter of introduction from David Moore (1808-1879), a well-known horticulturalist and garden designer. Moore was the director of the Royal Dublin Society's botanic garden at Glasnevin, County Dublin, and his recommendation would have carried much weight. In 1862 Robinson was duly taken on by the Royal Botanic Society at Regent's Park, and put in charge of its "educational and herbaceous department" (Nelson). Here, most of his early work was carried out under the helpful eye another famous landscape gardener, Robert Marnock (1880-1889), who had been in charge there for over twenty years, and was a firm believer in less formal, more natural landscaping and planting.

"Garden improvements in Regent's Park" shown (and discussed at length) in the Illustrated News of 1 August 1863.

A month's tour of other British botanical gardens, and a longer visit to France, again inspecting and reporting back on gardens and plant nurseries, broadened the Robinson's knowledge of available species and design possibilities. In Paris, he also attended the Universal Exhibition of 1862. With his name appearing in gardening periodicals in England, as well as in The Times, he was now becoming known, and he was elected a fellow of the Linnean Society of London on 19 April 1866. His first two books were based on his experiences in France: Gleaning from French Gardens (1868) and The Parks, Promenades and Gardens of Paris (1869). By now he had relinquished his post at Regent's Park and was writing full time. His later travels in other parts of Europe would also give him much new material, Settled in Kensington now, he wrote one of the books that really made his name: The Wild Garden. This was first published in 1870, but "evolved" through seven editions even during Robinson's own lifetime (Darke 7).

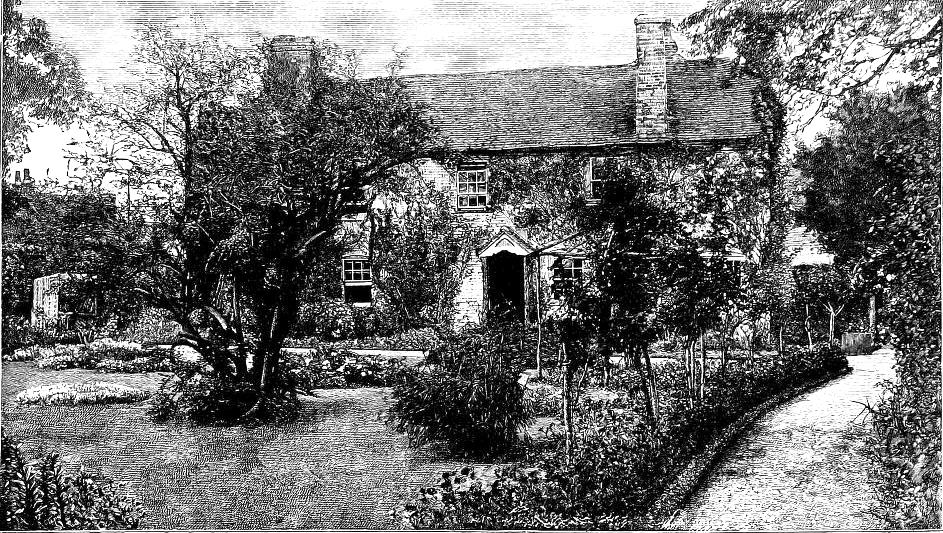

Left to right: (a) Cover of The English Flower Garden (9th ed.), showing a poppy. (b) Illustration of a violet in the same book, p. 33. (c) "Miss Yonge's Cottage at Elderfield," facing p. 74.

A trip to America followed — another episode about which little is known for sure. Next came more books, and then, late in 1871, the first number of his popular weekly magazine, The Garden. Others followed, including Gardening (later rechristened, Gardening Illustrated). But Nelson judges his most important work to be The English Flower Garden of 1883, beatifully illustrated by illustrator and engraver Armand-Emile-Jean-Baptiste Kohl (1845-(?)1928). This used some of his own earlier work, and work by other gardening experts, to make a highly popular compendium. "Fifteen editions, some reprinted several times, appeared during Robinson's lifetime" (Nelson). What appeals so much here is the interest he expresses in even small garden plots, homely spaces in which without any "pretentious 'plan'" the flowers are allowed to "tell their story to the heart" (38). One example he gives is of the novelist Charlotte Yonge's cottage at Otterbourne, Winchester, which inspires his comment, "The true flower garden is one in which there is, as in nature and life, ceaseless change" (70).

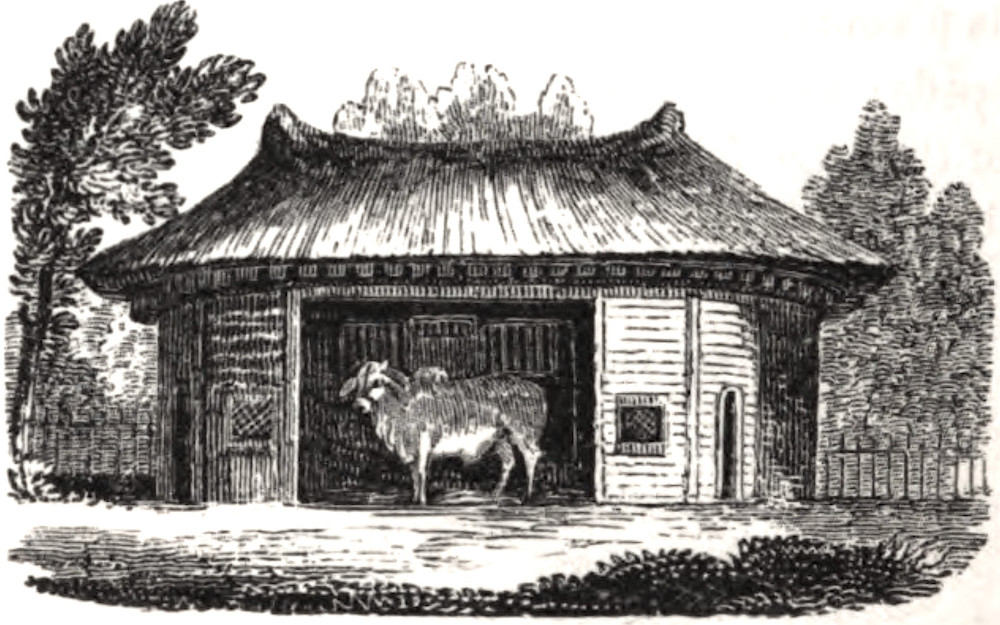

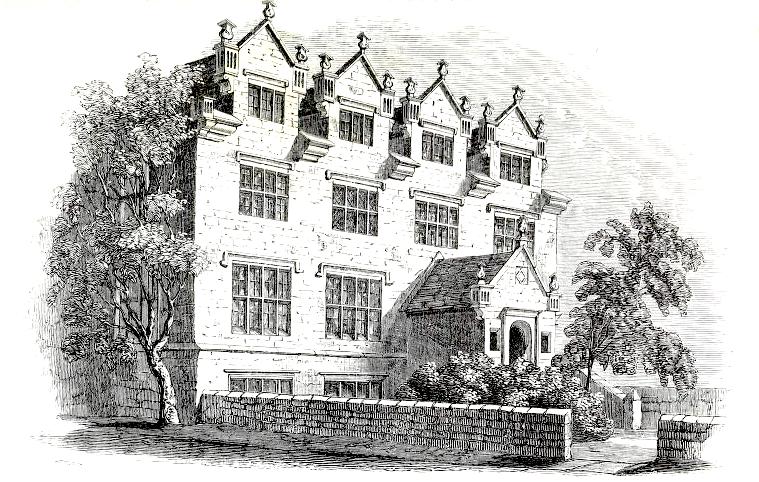

Gravetye Manor. Source: Blauuw, facing p. 166.

Able to live in some style now, Robinson bought something more substantial than a cottage — the sixteenth-century Gravetye Manor estate in Sussex in 1884. Here he lived for the rest of his life, doing a great deal of work on both house and garden, and continuing to write. From 1909 he was wheelchair-bound. Nevertheless, in 1932 he managed to attend the funeral service of his good friend Gertrude Jekyll in December 1932. He had once been a "frequent visitor" to her home at Munstead, and had "more than once lent his experienced hand in the laying out of the garden" (Jekyll 109). He died on 12 May 1935, and was cremated at Golder's Green Crematorium, which, as a long-time advocate of cremation, he himself had laid out.

People who knew Robinson had different views about him, some finding him difficult and opinionated, others admiring him hugely. The same goes for his achievement, that is, his successful dismissal of formal garden design, with its swathes of neatly arranged bedding plants, and his advocacy instead of restful views and mixed borders of hardy native and happily naturalised plants. To some, that makes him a real trail-blazer, while his detractors feel that he was merely a populariser. The truth, as always, must lie somewhere between these opposing views. As for the originality or otherwise of his ideas, the Gravetye Charity, which looks after his estate now, makes a sensible compromise. While his ideas about preserving native species, parks and green spaces, and so on, were ahead of their time, the Charity suggests that they were also "in tune with an increasing taste for simplicity as epitomised by the British Arts and Crafts movement.... and a resurgence of interest in the English Cottage garden."

Finally, was Robinson not so much in tune with current trends, as capitalising on them? His choice of landscape artist and (later) Hardy-illustrator Alfred Parsons for the appealing illustrations in The Wild Garden might confirm that. Both he and Parsons did cater for the Victorians' nostalgia for rural landscapes and ways of life: "The popularity of the wild garden lay in its promise of a richly planted rural landscape that could counteract the destructive effects of urbanization and industrialization and revive Englanders’ supposedly indigenous love of their rural countryside," says Anne Helmreich (111). Yet the end of Robinson's "explanatory" opening chapter in The Wild Garden is not about recreating "Olde England": it is a paean of praise for the exotic plants that might usefully take up residence here. Besides, nobody who reads his work will fail to recognise an authentic, personal conviction behind it. He was a bachelor, whose real passion was gardening. He made it his mission to change the way it was being done in England; and in large measure, he succeeded.

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

"About William Robinson." William Robinson Gravetye Charity. Web. 19 June 2022.

Blauuw, W. H. "Wakehurst, Slaugham and Gravetye." Sussex Archaeological Collections relating to the history and antiquities of the county. London: John Russell Smith, 1858. Internet Archive. From the collection of Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center. Web. 19 June 2022.

Darke, Rick. Introduction. The Wild Garden: Expanded Edition [an expansion of the 5th ed.]. Portland, Oregon and London: Timber Press, Inc., 2009. 7-13.

Helmreich, Anne. "Re-presenting Nature: Ideology, Art and Science in William Robinsonn's 'Wild Garden.' In Nature and Ideology: Natural Garden Design in the Twentieth Century. Edited by Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1977. 81-111.

Jekyll, Francis.

Nelson, E. Charles. "Robinson, William (1838–1935), horticulturist and publisher." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 19 June 2022.

Robinson, William. The English Flower Garden and home grounds.... 9th ed. London: John Murray, 1905. Internet Archive. From the collection of Cornell University Library. Web. 19 June 2022.

Created 20 June 2022