George Frederick Watts is principally known as a painter and sculptor, but like many others who were primarily engaged with the exhibition hall and salesroom he also turned his hand to book illustration. In this respect he is most closely linked to Frederic Leighton, another sculptor and painter with a small portfolio of images for the printed page. n the case of Watts the range of work is small indeed. Commissioned by the Dalziel Brothers to produce illustrations for their projected Bible in 1862–63, he completed just three engravings on wood: Noah Building the Ark, Noah’s Sacrifice and Esau Meeting Jacob. These were published in the Dalziels’ Bible Gallery in 1880–81 and again in 1894 in the form of Art Pictures from the Old Testament.

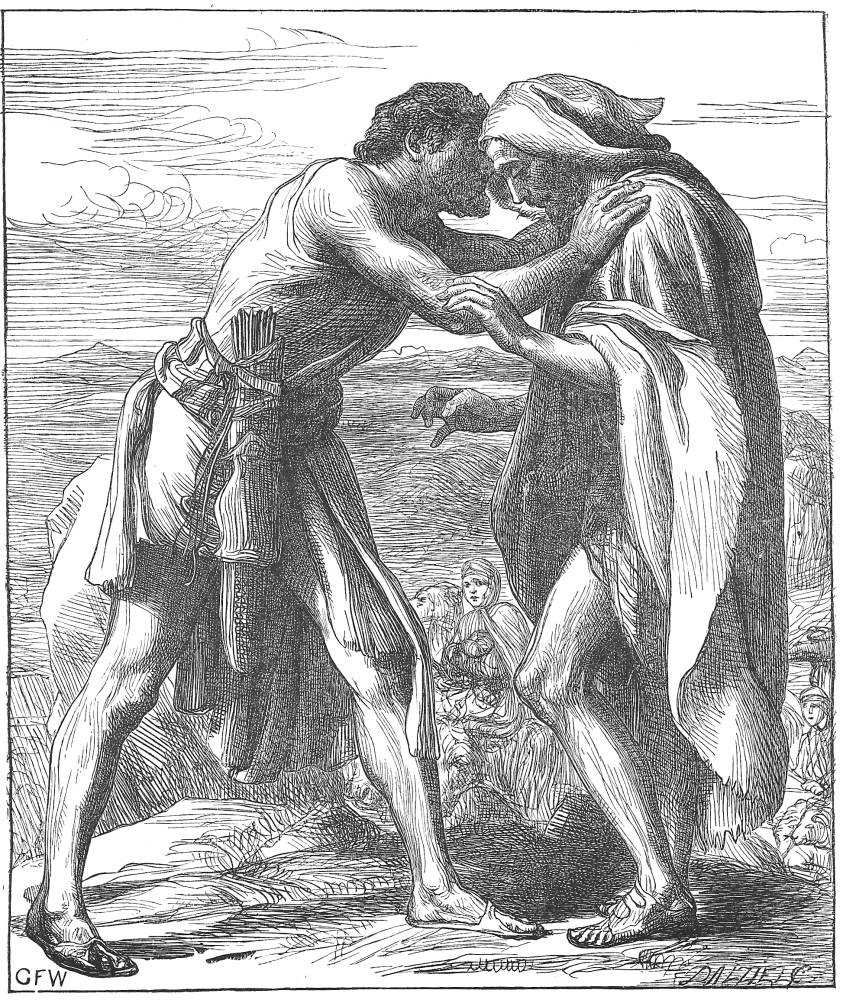

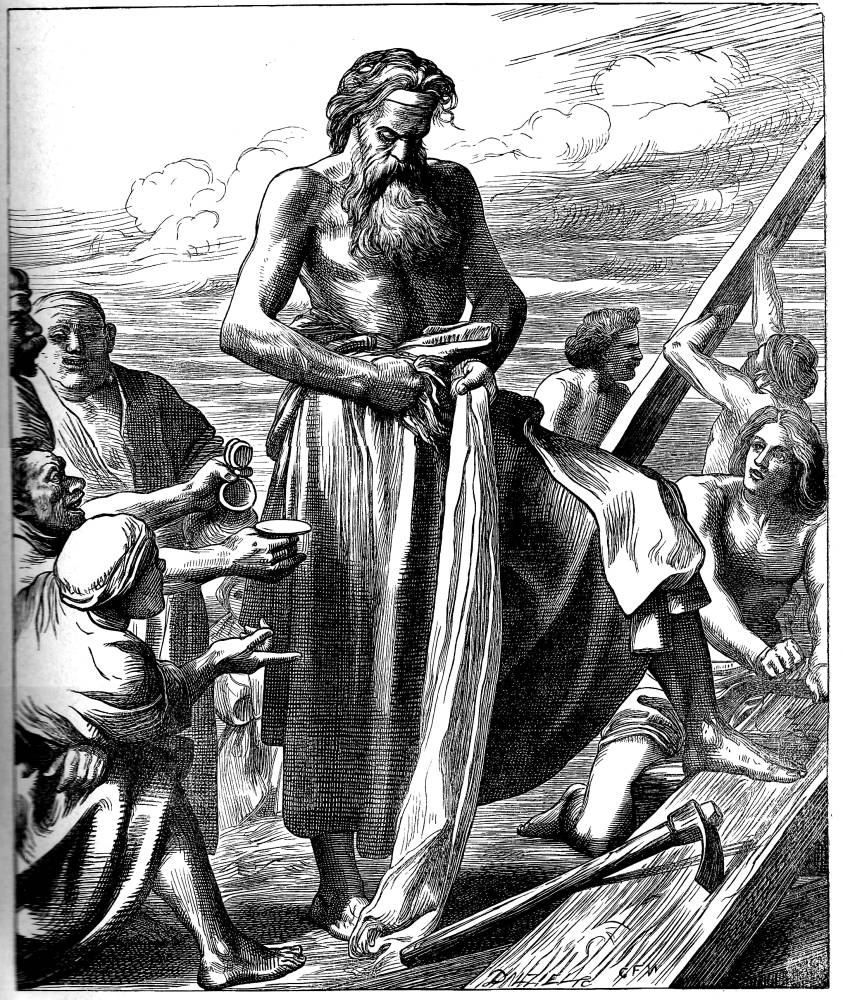

Left: Esau Meeting Jacob. Middle: The Good Samaritan. Right: Orpheus and Eurydice [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Watts’s contribution to the Dalziels’ epic venture was intended to be substantial but, like many of the contributors to this ill-fated book – which appeared almost twenty years after it was planned – he unexpectedly experienced a number of difficulties. He was too busy with his principal work and was significantly inhibited by his failure to master the technique of drawing on wood (Dalziels, Record, p. 244). He was not offered the option of having his work photographed and transferred to the block, and had to acquire a new set of skills – drawing designs from tracing paper or drawing directly with a brush or sharp pencil in reverse onto a whitened surface – which were not easily gained. As Forrest Reid explains, he started well but ‘found the medium baffling and after several attempts was inclined to withdraw from what now seemed to him a thankless task’ (p.207). There were also difficulties in his dealings with his employers. In common with Fred Sandys and Dante Rossetti, he resented the engravers’ intervention in the creation of his imagery, and was reluctant to allow them any aesthetic control. The Brothers’ ‘slight objection’ (Record, p.244) to aspects of the main figure in Noah Building the Ark was met with a reply in which he maintains a sort of frosty civility while conceding some small alterations:

I am always ready to receive and act upon criticism, and have therefore added a little to the size of the head of Noah … but my object is not to represent the phrenological characteristics of a mechanical genius, but the might and style of the inspired Patriarch … I have made drawing my principle study for many years and consider myself at liberty to depart from mere correctness if necessary for my purpose … if I do anything for you, or anybody else, I must carry out my own sentiment [Record, p.246].

Watts’s response typifies the struggle for authorship which is so much a part of the working relationships involved in the collaborative art of wood-engraving. Unfamiliar with the technique and irritated by what he saw as the impertinence of the technicians, it is barely surprising that he declined to produce more than three designs and regarded the whole process too exacting. Yet he might have benefitted from the Dalziels’ advice.

Left: Noah’s Sacrifice. Right: Noah Building the Ark. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In his letter to the engravers he insists that his version of Noah is more a ‘Patriarch’ than a ‘mechanical genius’, but it is unquestionably the case that his figure, who is stripped to the waist and has massive arms, looks more like a labourer than an ancient founder of dynasties. His huge frame dominates the composition and his stance, with one foot placed on a plank of gopher, is the visual embodiment of his determination to create the ark. In a period when the importance of the working classes was increasingly recognized by middle-class observers, who celebrated this discovery in publications such as The British Workman , his Noah seems an only lightly idealized version of the dignity of labour. The same figure appears in Noah’s Sacrifice while in the third, Esau Meeting Jacob, the emphasis is on the tenderness of the brothers’ greeting as Esau steps forward to embrace his sibling.

Realized in terms of monumental figures, contrapuntal designs and epic musculature, Watt’s illustrations closely reflect the style of his paintings. There is clearly a relationship between the patriarch in Noah Building the Ark and the neo-classical treatment of the figures in The Good Samaritan (1852, Manchester City Art Gallery), notably in the emphasis on the colossal forearms. The embrace in Esau Meeting Jacob is likewise a version of his painterly imagery and can be linked to the many canvases in which the artist explores the physical interactions between his characters. Esau’s extended arms are echoed in his two versions of The Good Samaritan, and also in the treatment of the figures in his Orpheus and Eurydice. There is an added dimension in that Watts’s designs are realized in sharp relief: the draughtsmanship is sculptural as much as painterly, and there is always an underlying sense of the influence of his exemplar, Michelangelo.

Deeply emotional and always ‘noble’ (Goldman, p. 211), Watts’s designs help to create the sense of sonorous melancholy that is otherwise registered in the Biblical illustrations of Sandys and Leighton. Grand in effect, they invoke a distinct sense of the heroic ideal. That Watts produced so little is unfortunate, and a loss to the graphic art of the Sixties.

Works Cited and Sources of Information

Art Pictures from the Old Testament and Our Lord’s Parables. With letterpress by Alex Foley. London: SPCK, 1894.

Brothers Dalziel, The. A Record of Work. 1901; rpt. London: Batsford, 1978.

Conroy, Carolyn. ‘Dalziels’ Bible Gallery: 1881’. http://www.simeonsolomon.com Accessed 20 June 2015.

Cooke, Simon. Illustrated Periodicals of the 1860s. Pinner: PLA, London: The British Library & Newcastle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2010. pp. 188–191.

Cooke, Simon. ‘Notable Books: The Dalziels’ Bible Gallery’. The Private Library 5th Series 10:2 (Summer 2007): 59–85.

Dalziel’s Bible Gallery. London: Routledge, 1881 [1880].

Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustration: The Pre-Raphaelites, the Idyllic School and the High Victorians. Aldershot: Scolar, 1996, 2004.

Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Eighteen Sixties. 1928; reprint, New York: Dover, 1975.

References

Dalziels’ Bible Gallery. London: George Routledge, 1881 [1880].

Created 23 July 2015