George Augustus Sala (1828-1895) is best known as a man of letters. Primarily a journalist, he wrote extensively for the Illustrated London News and The Daily Telegraph; he also contributed articles to Dickens’s magazines, Household Words and All the Year Round, as well as being the founding editor of Temple Bar. Regarded as one of the flamboyant characters of the age, who covered everything from the Crimean War to the art of Hogarth, he became well-known for his prolixity and self-indulgence. Less familiar is the fact that Sala had a parallel, albeit limited, career as a painter and graphic artist.

Sala had a very rudimentary training in art. Aged 14, he was apprenticed as a miniature painter under the direction of a Mr Schiller, a course of learning that was never completed, and thereafter he was self-educated (Sala, The Life and Adventures, 1: 142). He did drawings at home, sketching actors from the Princess’s theatre where his mother worked as an actress, and went on to sell watercolours ‘for a few shillings’ (1:150). He was later employed at the same theatre where he became a scene painter while undertaking a number of routine jobs. Other work as a visual artist included the production of lithographic labels for bottles (1: 148) and a painted scene on cloth for a local inn; his draughtsmanship was also developed by copying technical plans for railway companies. This informal, impromptu training was always enacted under economic pressure as Sala went in pursuit of employment, and his visual apprenticeship, as Peter Blake describes it (1), was anything but systematic.

Not surprisingly, he never acquired any advanced skills and was limited to working in the humorous cartoon style that was popular in the period from the 1830s until the middle of the century. His primary publications were three sets of ‘panoramas’ — satirical picture-books, issued in colour and black and white, that ridiculed the Great Exhibition by depicting a series of caricatures of foreign visitors and their national artefacts. Foremost among these is The Great Exhibition: ‘Wot is to Be’, which was issued in 1850 in anticipation of the event in 1851. Writing in 1895, Sala describes his work in detail:

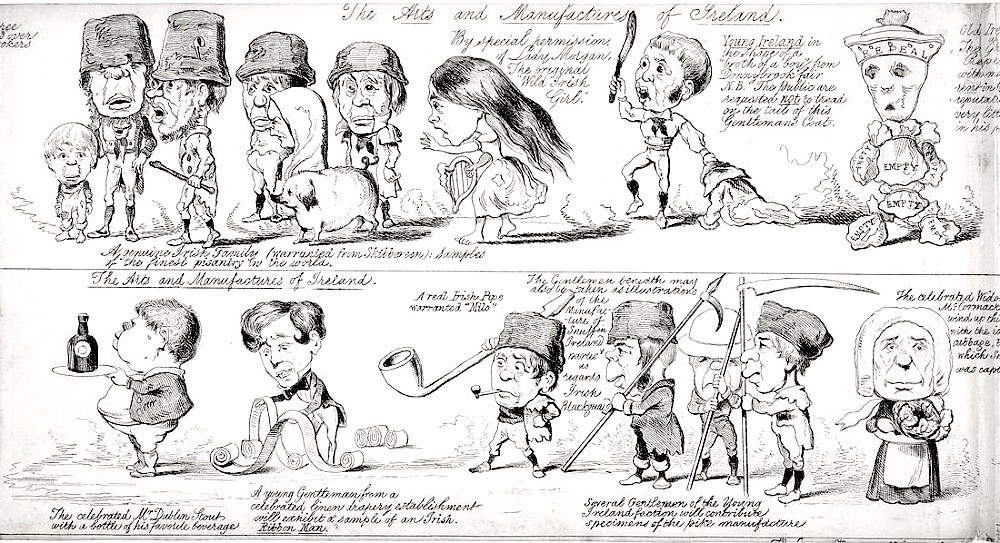

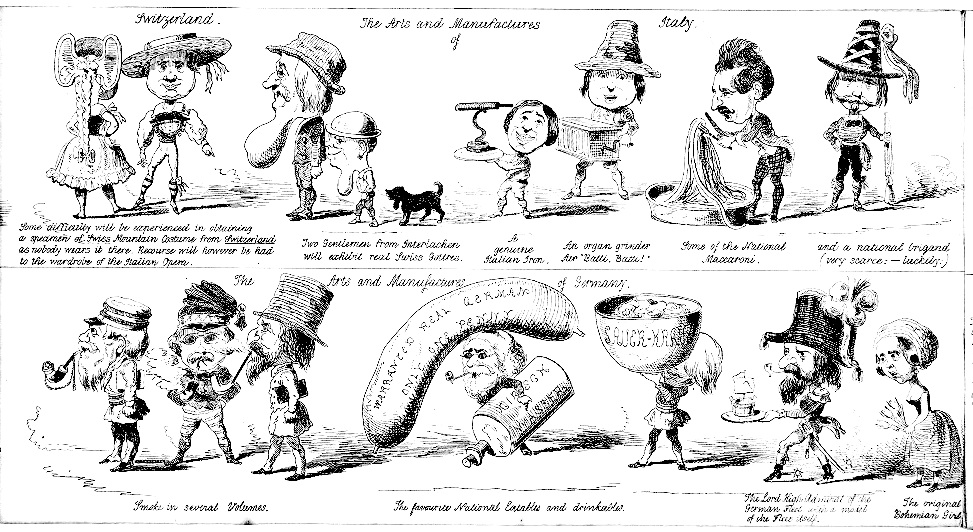

My book comprised many hundreds of farcical figures, all with very large heads and very diminutive bodies [including] Spanish Figaros and cachucha dancers; Americans revelling in sherry-cobblers, reposing in rocking-chairs, thrashing their slaves, and brandishing six-chambered pistols; Turks, Jews, and African savages; Scotch bagpipes and Irish boys and colleens. [Sala, 1: 216-17]

Conceived as a comic-strip of comedic faces and situations accompanied by ironic captions, The Great Exhibition exemplifies the humour and attitudes of the time and recalls the satirical style of Punch. To modern eyes it seems decidedly xenophobic or racist in tone, reducing each nationality to a racial type.

Sala’s take on Turkey and the Turks.

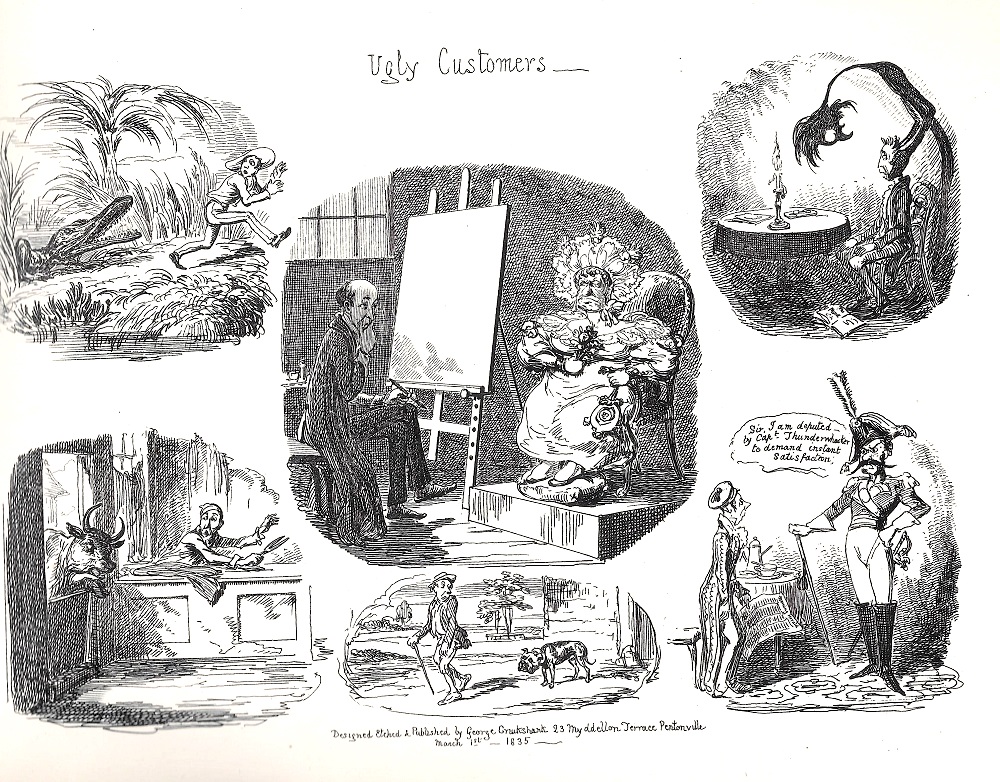

Sala's style is closely linked to George Cruikshank’s burlesque, and reproduces the combination of multiple figures arranged in vignettes that is found, for example, in Cruikshank’s Sketch Book [1834]. Following this example, Sala designed his picture-book as a rich field of amusing jests, and although he exaggerates the number of drawings — there are certainly not ‘many hundreds’ — the overall effect is one of intense inventiveness, combining sharp satirical hits with many close observations of social mores, both foreign and home-grown. To drive his points home, Sala divides each page into two tiers, a device that doubles the space available to his comic population, while referring to the arrangement of galleries in the Crystal Palace.

A typical page of comic vignettes by Cruikshank.

Sala’s racist representation of the Irish.

Sala’s commentary on the poor quality of contemporary domestic items.

Sala’s observations on the Italians, Swiss and Germans.

He followed The Great Exhibition: ‘Wot is to Be', with two others, The Great Glass House Opened and The House that Paxton Built. These were published in 1851 as souvenirs and, as Peter Edwards points out, had to compete with many similar titles, notably Richard Doyle’s An Overland Journey to the Great Exhibition (1851) and the anonymous Comic Game of the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Richard Doyle’s satirical view of Scots, Arabs, Germans and Italians.

Working within a distinct genre of books which offered a mocking topicality, Sala's contributions might thus be read as interesting examples of their type. He did a few other pieces of graphic satire, but quickly turned to writing rather than illustrating. It is a pity that he did not develop this aspect of his work: a talented if limited artist, his comic publications have largely slipped into obscurity. Worthy of reassessment, and always of interest as a historical record of mid-Victorian attitudes, they fit neatly into the comedic tradition that includes Cruikshank, Doyle, John Leech, Alfred Crowquill and Kenny Meadows.

Bibliography

Blake, Peter. George Augustus Sala: The Personal Style of a Public Writer. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Sussex, 2010.

The Comic Game of the Great Exhibition. London: Spooner, 1851.

Cruikshank, George. My Sketch Book. London: Tilt, 1835.

Doyle, Richard. An Overland Journey to the Great Exhibition. London: Chapman & Hall, 1851.

Edwards, Peter. "George Augustus Sala and his Panorama: The Great Exhibition: ‘Wot is to be'." Fryer Folios 1 (2006): 13-15.

Sala, G. A. The Great Exhibition: ‘Wot is to Be’. London: The Committee for Keeping Things in Their Places [Ackermann], 1850

Sala, G. A. The Great Glass House Opened. London: The Company of Painters and Glaziers [Ackermann], 1851.

Sala, G. A. The House that Paxton Built. London: Ironbrace, Woodenheard [Ackermann], 1851.

Sala, G. A. The Life and Adventures of George Augustus Sala. 2 Vols. New York: Scribner’s, 1895.

Created 1 September 2021