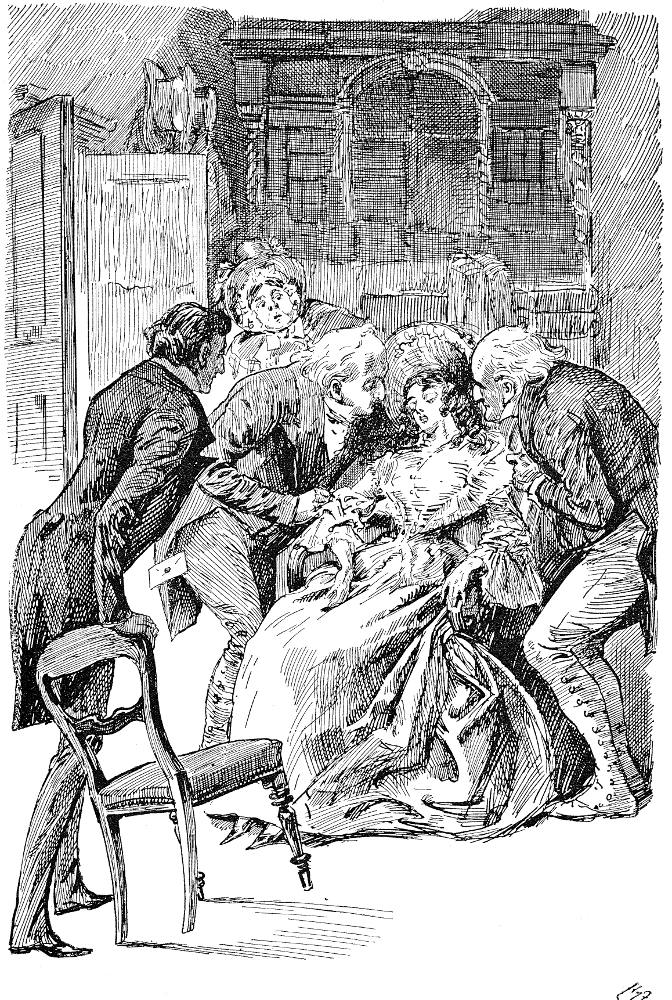

"I must speak to her — I will! I will not leave this house without." [Page 221] by Charles Stanley Reinhart (1875), in Charles Dickens's The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, Harper & Bros. New York Household Edition, for Chapter XL. 8.9 x 13.5 cm (3 ½ by 5 ¼ inches), framed. Running head: "Great Success of Newman Noggs" (221). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Nicholas in love with the mysterious Madeline Bray

Harry Furniss's interpretation of the fainting scene: Nicholas comes in upon an awkward scene (1910).

The young lady shrieked, the attendant wrung her hands, Nicholas gazed from one to the other in apparent stupefaction, and Newman hurried to and fro, thrusting his hands into all his pockets successively, and drawing out the linings of every one in the excess of his irresolution. It was but a moment, but the confusion crowded into that one moment no imagination can exaggerate.

"Leave the house, for Heaven’s sake! We have done wrong, we deserve it all," cried the young lady. "Leave the house, or I am ruined and undone for ever."

"Will you hear me say but one word?" cried Nicholas. "Only one. I will not detain you. Will you hear me say one word, in explanation of this mischance?"

But Nicholas might as well have spoken to the wind, for the young lady, with distracted looks, hurried up the stairs. He would have followed her, but Newman, twisting his hand in his coat collar, dragged him towards the passage by which they had entered.

"Let me go, Newman, in the Devil’s name!" cried Nicholas. "I must speak to her. I will! I will not leave this house without."

"Reputation — character — violence — consider," said Newman, clinging round him with both arms, and hurrying him away. "Let them open the door. We’ll go, as we came, directly it’s shut. Come.This way. Here."

Overpowered by the remonstrances of Newman, and the tears and prayers of the girl, and the tremendous knocking above, which had never ceased, Nicholas allowed himself to be hurried off; and, precisely as Mr. Bobster made his entrance by the street-door, he and Noggs made their exit by the area-gate. [Chapter XL, "In which Nicholas falls in Love. He employs a Mediator, whose Proceedings are crowned with unexpected Success, excepting in one solitary Particular," 222]

Commentary: A Curious Case of Double Mistaken Identity

Reinhart here is responding to Nixcholas's error in thinking that "Cecilia Bobster" is the mate that fate has intended for him. He acknowledges that the name "Cecilia" has music, but is quite certain that "Bobster" strikes a false note. He is, of course, quite correct: Newman Noggs has totally erred in identifying Nicholas's mysterious young lady as "Cecilia Bobster," although her father, too, is a domineering ogre. If only Newman had not been drinking pretty liberally before undertaking his post at the pump! He has identified both the wrong maid and the wrong young lady, as the closing lines of the chapter make clear.

In this illustration, Nicholas has yet to discover that the lady whom Noggs has identified as the mysterious young lady in Mr. Charles Cheeryble’s office is not Cecilia Bobster. Noggs has, through drinking while on the job of surveilling the town pump misidentified the maid, and so has led Nicholas to entirely the wrong place:

They hurried away, through several streets, without stopping or speaking. At last, they halted and confronted each other with blank and rueful faces.

"Never mind," said Newman, gasping for breath. "Don’t be cast down. It’s all right. More fortunate next time. It couldn’t be helped. I did my part."

"Excellently," replied Nicholas, taking his hand. "Excellently, and like the true and zealous friend you are. Only — mind, I am not disappointed, Newman, and feel just as much indebted to you — only it was the wrong lady."

"Eh?" cried Newman Noggs. "Taken in by the servant?"

"Newman, Newman," said Nicholas, laying his hand upon his shoulder: "it was the wrong servant too."

Newman’s under-jaw dropped, and he gazed at Nicholas, with his sound eye fixed fast and motionless in his head.

"Don’t take it to heart," said Nicholas; "it’s of no consequence; you see I don’t care about it; you followed the wrong person, that’s all."

That was all. Whether Newman Noggs had looked round the pump, in a slanting direction, so long, that his sight became impaired; or whether, finding that there was time to spare, he had recruited himself with a few drops of something stronger than the pump could yield — by whatsoever means it had come to pass, this was his mistake. And Nicholas went home to brood upon it, and to meditate upon the charms of the unknown young lady, now as far beyond his reach as ever. [XL, 222]

The "mystery" and "romance" in Reinhart's illustration degenerate into a farcical scene of mistaken identities. Anxious to get his young companion out of the house before Mr. Bobster appears, Newman Noggs restrains Nicholas from advancing to meet Cecilia Bobster. She reaches out for her beau, but is restrained by her maid, who attempts to pull her out of the darkened kitchen of tyhe decidedly middle-class house on the Edgeware Road.

It has not yet dawned on Nicholas that the young woman reaching out to him from across the kitchen is not the mystery lady. The settle, covered with pewter mugs, dies not merely establish the setting; such domestic realia foil the romantic plot and the hyperbolic emotions that Nicholas and the young woman express in passionate gestures, postures, and visages. Chiaroscuro plays dramatically on Nicholas's vest and face, and upon the skirts of the young lady and her maid's apron, as well as at the young lady's feet, intensifying the emotionalism of the scene — and heightening the farce when the discovers Noggs's error on the next page.

Other Editions' Versions of the Mystery of Madeline Bray (1839-1910)

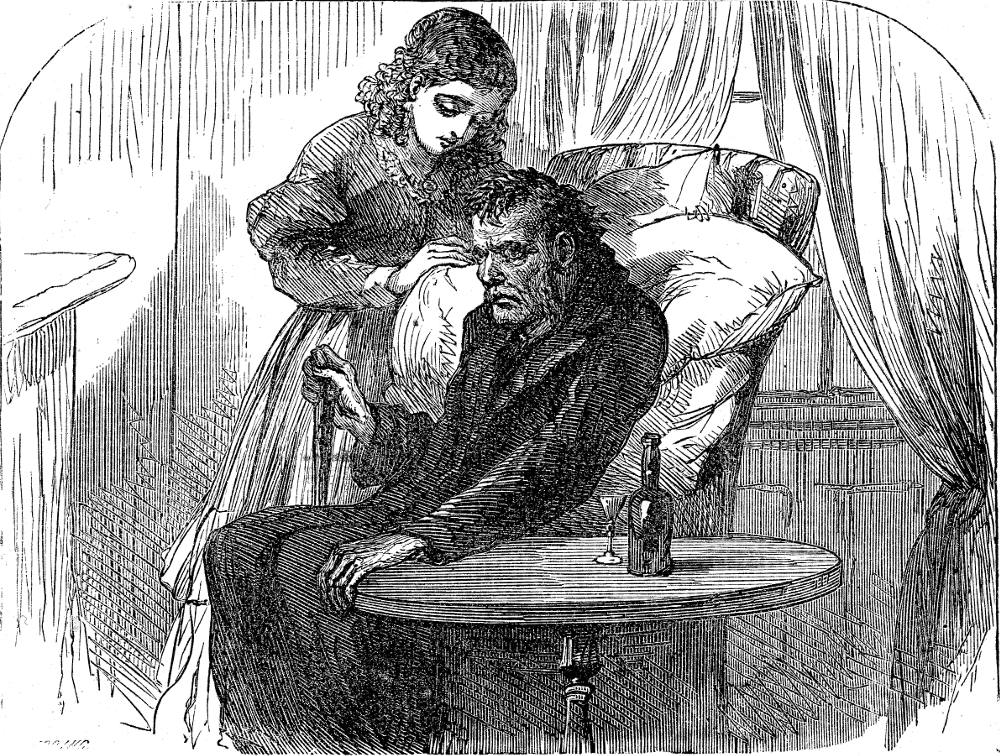

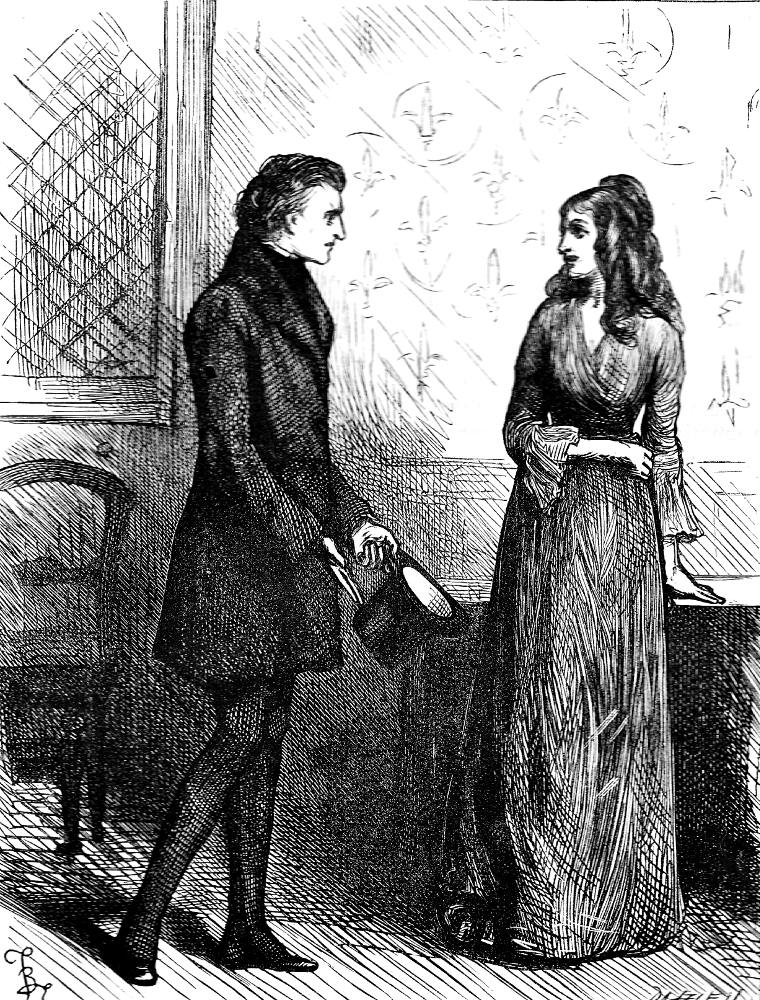

Left: Phiz brings in the romantic interest for the Nicholas plot: Nicholas Recognizes the Young Lady Unknown (April 1839). Right: Fred Barnard's British Household Edition interpretation of Noggs's serving as Nicholas's detective: The Meditative Ogre.

Left: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition study of the novel's belatedly introduced secondary heroine: Walter Bray and Madeline (1867). Right: Fred Barnard's 1875 woodblock engraving of the Nicholas and Madeline: "I must beseech you to contemplate again the fearful curse to which you have been impelled.", in the British Household Edition, Ch. 53.

Related material by other illustrators (1838 through 1910)

- Nicholas Nickleby (homepage)

- Phiz's 38 monthly illustrations for the novel, April 1838-October 1839.

- Cover for monthly parts

- Charles Dickens by Daniel Maclise, engraved by Finden

- "Hush!" said Nicholas, laying his hand upon his shoulder. (Vol. 1, 1861)

- The Rehearsal (Vol. 2, 1861)

- "My son, sir, little Wackford. What do you think of him, sir?" (Vol. 3, 1861)

- Newman had caught up by the nozzle an old pair of bellows . . . (Vol. 4, 1861).

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s 18 Illustrations for the Diamond Edition (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 59 Illustrations for the British Household Edition (1875)

- Harry Furniss's 29 illustrations for Nicholas Nickleby in the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Kyd's four Player's Cigarette Cards (1910).

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Barnard, J. "Fred" (il.). Charles Dickens's Nicholas Nickleby, with fifty-nine illustrations. The Works of Charles Dickens: The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1875. Volume 15. Rpt. 1890.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. With fifty-two illustrations by C. S. Reinhart. The Household Edition. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1875.

__________. "Nicholas Nickleby." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings by Fred Barnard et al.. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1908.

Schweitzer, Maria. "Jean Margaret Davenport." Ambassadors of Empire: Child Performers and Anglo-American Audiences,

1800s-1880s. Accessed 19 April 2021. Posted 7 January 2015.

Created 31 August 2021