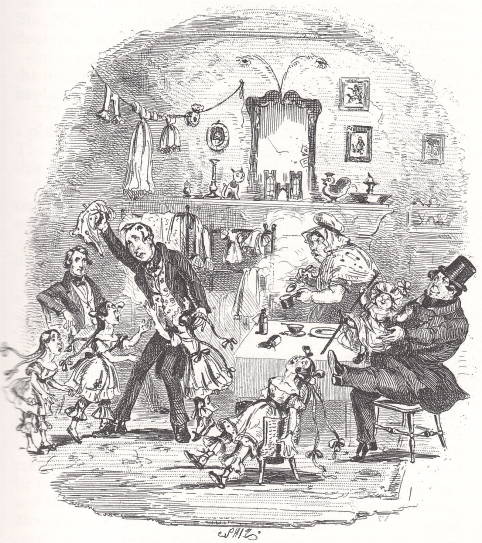

"I should say," said Mr. Kenwigs, abruptly, and raising his voice as he spoke, "that my children might come into a matter of a hundred pounds apiece, perhaps." [Page 196] by Charles Stanley Reinhart (1875), in Charles Dickens's The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, Harper & Bros. New York Household Edition, for Chapter XXXVI. 9 x 13.7 cm (3 ½ by 5 ⅜ inches), framed. Running head: "Petrifying Intelligence" (197). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Nicholas Announces the Marriage of Mr. Lillyvick to Kenwigs

Well, Mr. Kenwigs," said Dr. Lumbey, "this makes six. You’ll have a fine family in time, sir."

"I think six is almost enough, sir," returned Mr. Kenwigs.

"Pooh! pooh!" said the doctor. "Nonsense! not half enough."

With this, the doctor laughed; but he didn’t laugh half as much as a married friend of Mrs. Kenwigs’s, who had just come in from the sick chamber to report progress, and take a small sip of brandy-and-water: and who seemed to consider it one of the best jokes ever launched upon society.

"They’re not altogether dependent upon good fortune, neither," said Mr Kenwigs, taking his second daughter on his knee; "they have expectations."

"Oh, indeed!" said Mr. Lumbey, the doctor.

"And very good ones too, I believe, haven’t they?" asked the married lady.

"Why, ma’am," said Mr. Kenwigs, "it’s not exactly for me to say what they may be, or what they may not be. It’s not for me to boast of any family with which I have the honour to be connected; at the same time, Mrs Kenwigs’s is — I should say," said Mr. Kenwigs, abruptly, and raising his voice as he spoke, "that my children might come into a matter of a hundred pound apiece, perhaps. Perhaps more, but certainly that."

"And a very pretty little fortune," said the married lady.

"There are some relations of Mrs. Kenwigs’s," said Mr. Kenwigs, taking a pinch of snuff from the doctor’s box, and then sneezing very hard, for he wasn’t used to it, "that might leave their hundred pound apiece to ten people, and yet not go begging when they had done it." [Chapter XXXVI, "Private and confidential; relating to Family Matters. Showing how Mr Kenwigs underwent violent Agitation, and how Mrs. Kenwigs was as well as could be expected," 196-197]

Commentary: Kenwigs Counts His Chickens

Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition study of the growing family in need of inheritances: The Kenwigs Family and Mr. Lillyvick (Chapter 52) (1867).

Despite the arrival of sixth child and his wife's continuing "confinement," Kenwigs is in a sanguine mood. After all, the latest arrival is boy (whose birth he contemplates proudly announcing in the newspaper) and his children may well come into substantial inheritances when Mrs. Kenwigs's uncle, the miserly London rate-collector, dies. As the attending physician, Dr. Lumley, dandles last-year's infant before the doting father, the neighbour drinks brandy-and-water, but leaves the supervision of the other children to the eldest, the dictatorial Morleena. Shortly, however, Nicholas will disrupt the domestic idyll with the latest news from Portsmouth: Lillyvick has just married the Drury Lane actress Henrietta Petowker. Suddenly Kenwigs's hopes for his children's fortunes are dashed as the new wife will inherit all.

Reinhart's treatment seems distinctly more theatrical and less strictly realistic than Fred Barnard's (although markedly more realistic than the Phiz original) as the sixties illustrator renders the controlling Morleena Kenwigs and her father, as well as the attending physician, with caricatural visages. The scene in the parlour is crowded, to suggest the tight quarters in the growing family lives, although the mirror above the mantelpiece and the framed print on the wall suggest Kenwigs's middle-class pretentions. The single, vacant, tiny chair implies a shortage of such chairs among a menage of six young children. Physically as well as financially, suggests Reinhart, the family live in constrained circumstances. And Lillyvick's inheritance, which might have secured the futures of these children, is about to vanish.

Other Editions' Versions of the The Kenwigses (1839-1910)

Left: Phiz treats the same subject with considerably more caricature and more than a dash of farce as Nicholas delivers the bad news: Emotion of Mr. Kenwigs on Hearing the Family News from Nicholas (February 1839), Chapter 36. Right: Fred Barnard's 1875 woodblock engraving of the same comic scene: With this the doctor laughed; but he didn't laugh half as much as a married friend of Mrs. Kenwig's, who had just come in from the sick chamber — Chap. XXXVI in the British Household Edition.

Related material by other illustrators (1838 through 1910)

- Nicholas Nickleby (homepage)

- Phiz's 38 monthly illustrations for the novel, April 1838-October 1839.

- Cover for monthly parts

- Charles Dickens by Daniel Maclise, engraved by Finden

- "Hush!" said Nicholas, laying his hand upon his shoulder. (Vol. 1, 1861)

- The Rehearsal (Vol. 2, 1861)

- "My son, sir, little Wackford. What do you think of him, sir?" (Vol. 3, 1861)

- Newman had caught up by the nozzle an old pair of bellows . . . (Vol. 4, 1861).

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s 18 Illustrations for the Diamond Edition (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 59 Illustrations for the British Household Edition (1875)

- Harry Furniss's 29 illustrations for Nicholas Nickleby in the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Kyd's four Player's Cigarette Cards (1910).

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Barnard, J. "Fred" (il.). Charles Dickens's Nicholas Nickleby, with fifty-nine illustrations. The Works of Charles Dickens: The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1875. Volume 15. Rpt. 1890.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. With fifty-two illustrations by C. S. Reinhart. The Household Edition. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1875.

__________. "Nicholas Nickleby." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings by Fred Barnard et al.. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1908.

Schweitzer, Maria. "Jean Margaret Davenport." Ambassadors of Empire: Child Performers and Anglo-American Audiences,

1800s-1880s. Accessed 19 April 2021. Posted 7 January 2015.

Created 23 August 2021