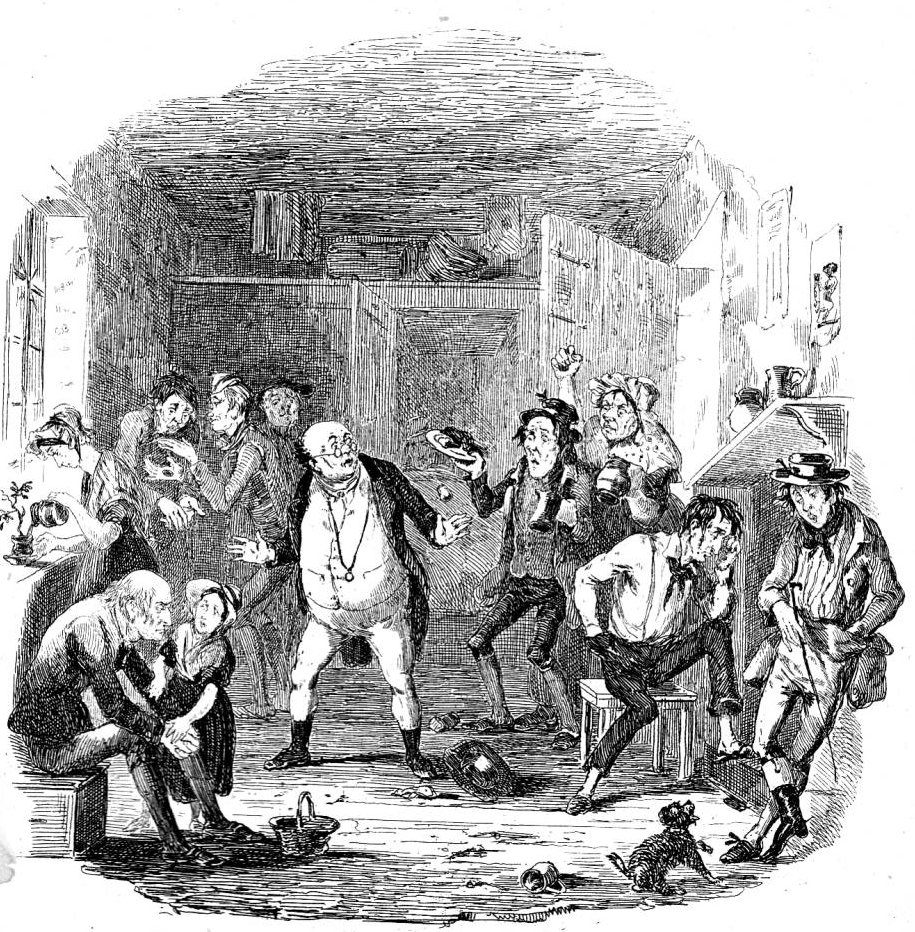

Letting his hat hat fall on the floor, he stood perfectly fixed and immovable with astonishmen by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne). Household Edition (1874) of Dickens's Pickwick Papers, opposite p. 298; scene realised, p. 298. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

As in the original illustration for July 1837, "The Discovery of Jingle in the Fleet," in Phiz's full-page redrafting for the woodcut medium used exclusively in the Household Edition (see plate at right), Pickwick is startled to discover an uncharacteristically despondent Alfred Jingle in the common room of the Fleet Prison. The 1873 woodcut is a reasonably faithful translation of the 1837 engraving, except, of course, that whereas "The Discovery of Jingle in the Fleet" is vertical in its orientation, "Letting his hat hat fall on the floor, he stood perfectly fixed and immovable with astonishment" is horizontal, and, as a full-page (framed) illustration measuring 12.4 by16.9 cm, it is reproduced on a much larger scale than the original vignetted engraving that is roughly 11 cm. square. The "Tom Rakewell" moment of degradation for Alfred Jingle and the simultaneous moment of recognition for Pickwick realised by both illustrations occurs opposite each picture, in chapter 42:

The general aspect of the room recalled him to himself at once; but he had no sooner cast his eye on the figure of a man who was brooding over the dusty fire, than, letting his hat fall on the floor, he stood perfectly fixed and immovable with astonishment.

Yes; in tattered garments, and without a coat; his common calico shirt, yellow and in rags; his hair hanging over his face; his features changed with suffering, and pinched with famine — there sat Mr. Alfred Jingle; his head resting on his hands, his eyes fixed upon the fire, and his whole appearance denoting misery and dejection!

Near him, leaning listlessly against the wall, stood a strong-built countryman, flicking with a worn — out hunting — whip the top-boot that adorned his right foot; his left being thrust into an old slipper. Horses, dogs, and drink had brought him there, pell-mell. There was a rusty spur on the solitary boot, which he occasionally jerked into the empty air, at the same time giving the boot a smart blow, and muttering some of the sounds by which a sportsman encourages his horse. He was riding, in imagination, some desperate steeplechase at that moment. Poor wretch! He never rode a match on the swiftest animal in his costly stud, with half the speed at which he had torn along the course that ended in the Fleet.

On the opposite side of the room an old man was seated on a small wooden box, with his eyes riveted on the floor, and his face settled into an expression of the deepest and most hopeless despair. A young girl — his little grand — daughter — was hanging about him, endeavouring, with a thousand childish devices, to engage his attention; but the old man neither saw nor heard her. The voice that had been music to him, and the eyes that had been light, fell coldly on his senses. His limbs were shaking with disease, and the palsy had fastened on his mind.

There were two or three other men in the room, congregated in a little knot, and noiselessly talking among themselves. There was a lean and haggard woman, too — a prisoner's wife — who was watering, with great solicitude, the wretched stump of a dried-up, withered plant, which, it was plain to see, could never send forth a green leaf again — too true an emblem, perhaps, of the office she had come there to discharge.

Such were the objects which presented themselves to Mr. Pickwick's view, as he looked round him in amazement. The noise of some one stumbling hastily into the room, roused him. Turning his eyes towards the door, they encountered the new-comer; and in him, through his rags and dirt, he recognised the familiar features of Mr. Job Trotter.

"Mr. Pickwick!" exclaimed Job aloud.

"Eh?" said Jingle, starting from his seat. "Mr. — ! So it is — queer place — strange things — serves me right — very." Mr. Jingle thrust his hands into the place where his trousers pockets used to be, and, dropping his chin upon his breast, sank back into his chair.

Mr. Pickwick was affected; the two men looked so very miserable. The sharp, involuntary glance Jingle had cast at a small piece of raw loin of mutton, which Job had brought in with him, said more of their reduced state than two hours' explanation could have done. [Chapter 42; in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition, p. 298]

Taking his cues from Dickens's descriptions of the various inmates, Phiz has focussed on two characters in the centre of the composition — Mr. Pickwick in a melodramatic "recognition" pose (toned down somewhat in the 1873 composition), and Jingle sitting on a stool (in 1873, a chair) with a vacant gaze and in a slumping posture suggestive of deep melancholy, one slippered foot on the fender. However, the illustrator also features the mad huntsman prominently (right), leaning beside the diminutive fireplace (rather than the wall, as in the text). In the background, Phiz has incorporated the knot of three (rather than the text's "two or three") men conversing noisily at the window, and the prisoner's wife (certainly "lean," but not "haggard") tending the dessicated plant at the grimy window (left). He has also filled out the scene with a pair of figures whom Dickens does not describe: a Hogarthesque harridan (who is not nearly so unpleasant in the 1873 revision) immediately behind Job Trotter, and — in the original but not in the woodcut — a barking Yorkshire terrier at the huntsman's slippered foot (which becomes a pair of Wellington boots in the 1873 revision).

In the original plate, considerable subtlety of commentary is involved in Phiz's positioning of the attentive little dog, trying in vain to engage his distracted master's attention, for he parallels the granddaughter (left, a mere careworn child in the 1837 engraving, but a respectably dressed young woman in the 1873 woodcut) who fruitlessly tries to rouse her grandfather to an awareness of her and their surroundings. In both of these Phiz illustrations, she expresses tender concern for her grandfather as she attempts to take him by the hand. But the most significant visual interpolation, already noted, is the alcoholic female entering the common room just behind Job Trotter. Her raised fist suggests her impatience with Job's blocking her way, giving her an inner life — Phiz's ironically implied observation is that she is in a hurry, with no place to go. The two illustrations, distinguished primarily by orientation and medium, differ too in a more subtle way in that the earlier engraving is an homage to the "progresses" of eighteenth-century narrative-pictorial satirist William Hogarth (1697-1764) — such as the six engravings that make up the unfortunate trajectory of Moll Hackabout, A Harlot's Progress (1732), and Marriage A-la-Mode (1745), whereas the remodelling of the figures into a more realistic Sixties style seems to have resulted in a loss of Hogarthian vigour, as the 1873 woodcut derives from Phiz's 1837 "Discovery of Jingle in the Fleet" rather than directly from, for example, "Tom Rakewell in Prison" in A Rake's Progress (1735). The slender figures, the social satire, the view of London low-life and the criminal underclass, the satire of social institutions such as the Church and the law, and the embedding of textual and visual symbols that serve as subtle commentaries on the characters and situations depicted — these features are all associated with the engravings and paintings of William Hogarth, the eighteenth-century English artist noted for his satirical narrative paintings and engravings that satirise contemporary vices and affectations. In his old age, Hablot Knight Browne seems to have lost his taste for social satire, as, for example, his depicting the "mad huntsman" in boots in the 1873 woodcut rather than a boot and a slipper. Although the Household Edition illustration is sharper, its space and figures more clearly defined, it lacks the exuberance of the original, as if it has lost its moral "inner life" because it no longer graphs the decay of the modern European city as Hogarth had done repeatedly.

Related Material

- The original May 1837 of this scene by Phiz: “Mr. Pickwick sits for his Portrait”

- The complete list of illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the original edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

References

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Dickens, Charles. The Pickwick Papers (1836-37). Il. Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman & Hall.

Dickens, Charles. "The Pickwick Papers. Il. Hablot Knight Browne. The Household Edition. London: Chapman & Hall, 1874.

Fort, Bernadette, and Angela Rosenthal. The Other Hogarth: Aesthetics of Difference. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U. P., 2001.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens. Vol. 1. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting by George P. Landow. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Pickwick Papers. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874; New York: Harpers, 1874.

Last modified 20 April 2012