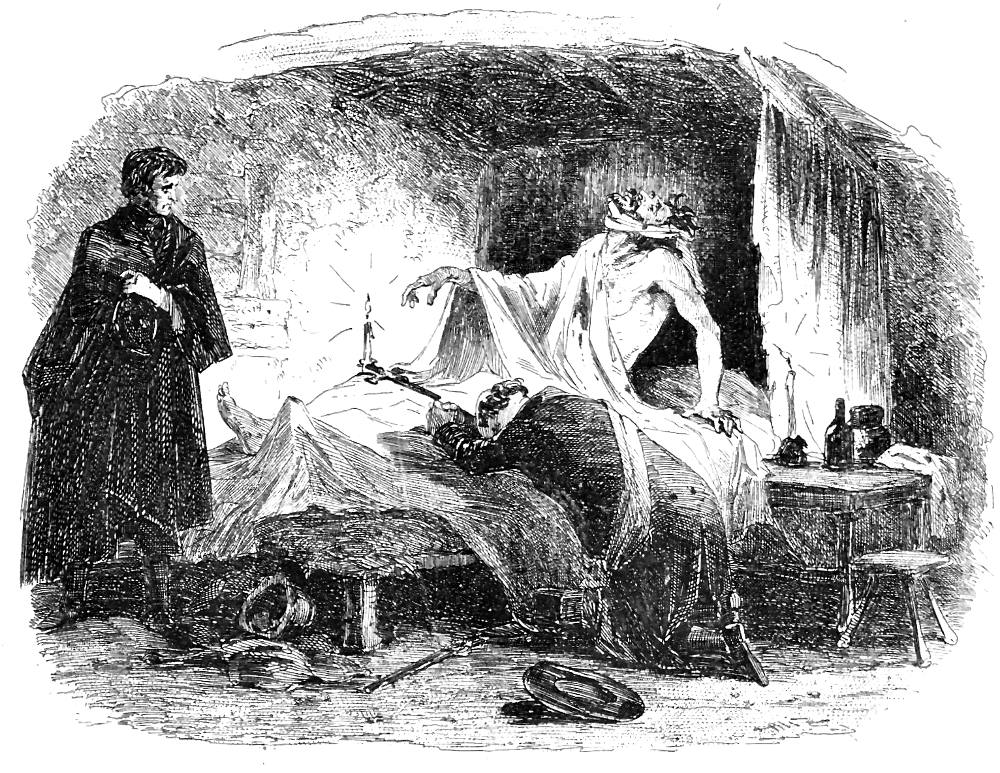

Death of Shaun, fifteenth steel-engraving and twenty-fourth serial illustration for Charles Lever's Jack Hinton, The Guardsman, Part 8 (August 1842), Chapter XXXIV, "The Mountain Pass." 9.6 by 12.6 cm (3 ¾ by 4 ⅞ inches), vignetted, facing p. 229. [Click on the illustration to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: A Gothic Tale set in the Forbidding Mountains

As I looked in horror at the frightful spectacle before me, my foot struck at something beneath the bed. I stooped down to examine, and found it was a carbine, such as dragoons usually carry. It was broken at the stock and bruised in many places, but still seemed not unserviceable. Part of the butt-end was also stained with blood. The clothes of the dead man, clotted and matted with gore, were also there, adding by their terrible testimony to the dreadful fear that haunted me. Yes, everything confirmed it — murder had been there.

A low, muttering sound near made me turn my head, and I saw the priest kneeling beside the bed, engaged in prayer. His head was bare, and he wore a kind of scarf of blue silk, and the small case that contained the last rites of his Church was placed at his feet. Apparently lost to all around, save the figure of the man that lay dead before him, he muttered with ceaseless rapidity prayer after prayer — stopping ever and anon to place his hand on the cold heart, or to listen with his ear upon the livid lips; and then resuming with greater eagerness, while the big drops rolled from his forehead, and the agonising torture he felt convulsed his entire frame.

'O God!' he exclaimed, after a prayer of some minutes, in which his features worked like one in a fit of epilepsy — 'O God, is it then too late?'

He started to his feet as he spoke, and bending over the corpse, with hands clasped above his head, he poured forth a whole torrent of words in Irish, swaying his body backwards and forwards, as his voice, becoming broken by emotion, now sank into a whisper, or broke into a discordant shout. 'Shaun, Shaun!' cried he, as, stooping down to the ground; he snatched up the little crucifix and held it before the dead man's face; at the same time he shook him violently by the shoulder, and cried, in accents I can never forget, some words aloud, among which alone I could recognise one word, 'Thea' — the Irish word for God. He shook the man till his head rocked heavily from side to side, and the blood oozed from the opening wound, and stained the ragged covering of the bed.

At this instant the priest stopped suddenly, and fell upon his knees, while with a low, faint sigh he who seemed dead lifted his eyes and looked around him; his hands grasped the sides of the bed, and, with a strength that seemed supernatural, he raised himself to a sitting posture. His lips were parted and moved, but without a sound, and his filmy eyes turned slowly in their sockets from one object to another, till at length they fell upon the little crucifix that had dropped from the priest's hand upon the bed. In an instant the corpse-like features seemed inspired with life; a gleam of brightness shot from his eyes; the head nodded forward a couple of times, and I thought I heard a discordant, broken sound issue from the open mouth; but a moment after the head dropped upon the chest, and the hands relaxed, and he fell back with a crash, never to move more. [Chapter XXXIV, "The Mountain Pass," pp. 228-229]

Commentary: An Atmospheric Setting

In dealing with his publisher regarding his new editorial post at The Dublin University Magazine Charles Lever was determined to rival Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine — Maga — in sales. And one of the ways in which he intended to do so was to render Hibernian versions of the Blackwood's tale of terror, a Gothic short story with weird, supernatural overtones and an emotionally charged, atmospheric setting. Thus, with the mysterious figure of a woman in the road and a "heartrending cry" does Lever introduce his version of a Blackwood's tale of the type that Dickens had attempted in "The Black Veil" (8 February 1836), collected in Sketches by Boz. To intensify the sense of the uncanny Lever never reveals what happened to Shaun and his wife. Phiz takes as his cue for depicting Shaun Lever's description of him:

In one corner of the hovel, stretched upon a bed whose poverty might have made it unworthy of a dog to lie in, lay the figure of a large and powerfully-built man, stone dead. His eyes were dosed, his chin bound up with a white cloth, and a sheet, torn and ragged, was stretched above his cold limbs, while on either side of him two candles were burning. His features, though rigid and stiffened, were manly and even handsome — the bold character of the face heightened in effect by his beard and moustache, which appeared to have been let grow for some time previous, and whose black and waving curl looked darker from the pallor around it. [228]

This is not, like so many of the reminiscences in the picaresque novel, an interpolated tale. Rather, the narrator is Hinton himself, represented by the young man in black to the left who observes the priest, Father Tom Loftus (right), prostrate on the deathbed, and the murdered young man, Shaun. The uncanny part of the tale is that Shaun, apparently dead from a knife attack and a bullet wound, rises up in the bed, as Phiz shows him, and then falls back, now certainly dead. Thus, Hinton can with a clear conscience tell those who arrive in a wagon with a coffin the next morning that the priest has administered the last rites to the dying man. It is not clear what their relationship is to young husband whose wife, Mary, Jack and Father Tom had encountered in the road outside the mud hut the evening before. Mickey and old Hugh bury Shaun in a shallow grave, and the priest promises not to set the police on them.

Related Material

- "The Blackwood's Tale": An Enduring Legacy

- "Phiz" — artist, wood-engraver, etcher, and printer — and the new reproductive processes

- The Novels of Charles Lever, 1839-72

- Phiz's Forty-four Illustrations for Lever's Charles O'Malley, The Irish Dragoon (1840-41)

- Phiz's Forty Illustrations for Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-44)

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Lever, Charles. Jack Hinton, The Guardsman. Illustrated by Hablột Knight Browne (Phiz). London: Downey & Co., 1901. [First published serially in The Dublin University Magazine January through December 1842; and subsequently in a single volume, Dublin: William Curry, Jun. December 1842, pp. 396. Illustrated with wood and steel engravings by H. K. Browne: 27 full-page plates. 8vo, 396pp. Boston: Little, Brown, 1894; New York: Croscup, 1894. 2 vols.

Stevenson, Lionel. Chapter VI, "Editor, 1841-1843." Dr. Quicksilver: The Life of Charles Lever. London: Chapman and Hall, 1939. 92-107.

Sutherland, John A. "The Dublin University Magazine." The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford U. P., 1989, rpt. 1990, 200.

Thomson, David Croal. Life and Labours of Hablột Knight Browne, "Phiz". London: Chapman and Hall, 1884.

Created 29 May 2023