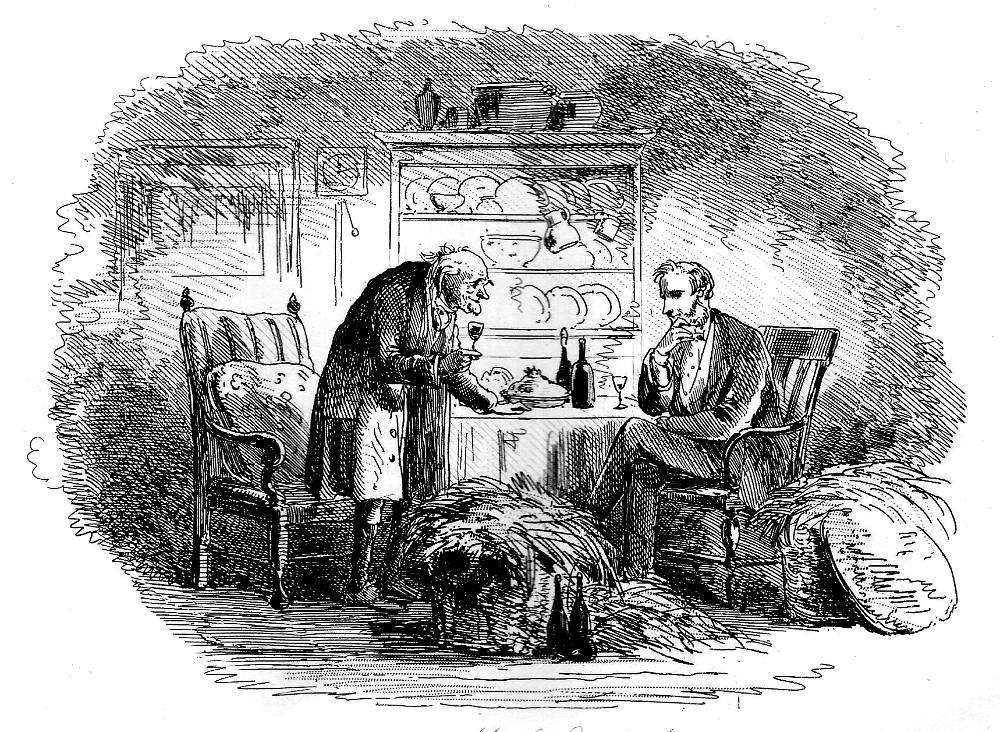

My Lord (November 1858) by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne), thirty-fourth serial illustration for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Time, Part 17 (November 1858), Chapter LXIII, "A Supper," facing 538.

Bibliographical Note

This appeared as the thirty-fourth serial illustration for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Time, steel-plate etching; 4 by 6 ½ inches (10 cm high by 16.3 cm wide), vignetted. The story was originally serialised by Chapman and Hall in monthly parts, from July 1857 through April 1859. The thirty-forth and thirty-fifth illustrations in the volume initially appeared in the reverse order at the very beginning of the seventeenth monthly instalment, which went on sale on 1 November 1858. This number included Chapters LXI through LXIV, and ran from page 513 through 544 to make up the 32-page instalment.

Passage Illustrated: Davenport Dunn at Home once again

“And what name do they give this, Davy?” said he, as he held up his glass to the light.

“Burgundy, father, — the king of wines. The wine-merchant names this Chambertin, which was the favourite drinking of the great Napoleon.”

“I wonder at that, now,” said the old man, sententiously.

“Wonder at it! And why so, father? — is it not admirable wine?”

“It's just for that reason, Davy; every sup I swallow sets me a-dreaming of wonderful notions, — things I know the next minute is quite impossible, — but I feel when the wine is on my lips as if they were all easy and practicable.”

“After all, father, just remember that you cannot imagine anything one half so strange as the change in our own actual condition. There you sit, with your own clear head, to remind you of when and how you began life, and here am I! — for I am, as sure as if I held my patent in my hand, the Right Honourable Lord Castledunn.”

“To your Lordship's good health and long life,” said the old man, fervently.

“And now to a worthier toast, father, — Lady Castledunn that is to be.”

“With all my heart. Lady Castledunn, whoever she is.”

“I said, 'that is to be,' father; and I have given you her name, — the Lady Augusta Arden.”

“I never heard of her,” muttered the old man, dreamily.

“An Earl's daughter, sir; the ninth Earl of Glengariff,” said Dunn, pompously. [Chapter LXIII, "A Supper," p. 538]

Commentary: Dunn Momentarily Triumphant

"In one word, if I leave this room without your distinct pledge on the subject, you will no longer reckon me amongst the followers of your party.” [525] — Davenport Dunn in conversation with the Prime Minister, Lord Jedburgh, threatens to withdraw his influence in Ireland unless the governing party supports the Glengariff allotments. Just as Dunn is preparing to leave Downing Street, the Prime Minister concedes the point, and thereby seems to assure Dunn's financial survival at the close of Chapter LXI, "Downing Street." However, since the political leader with whom Dunn negotiates is not John Henry Temple, Viscount Lord Palmerston, readers would have recognised that these chapters constitute a purely fictional account of the crisis of popular confidence in the British government in 1855.

Readers familiar with the tragic figure of John Sadleir would have viewed Dunn's savior faire as ill-founded, given the very real financial danger in which he finds subsequently himself. However, at this point in the narrative Lever implies that Davenport Dunn's future plans to marry Lady Augusta and join the peerage of Great Britain will meet with no check or impediment.

It is now a late evening in the autumn of 1855, concluding a summer of political and financial turmoil, and echoes of the military actions in the Crimea. Lever has shown readers this room and its principal occupant, old Matthew Dunn, before, in Chapter XV, "A Home Scene," in the cottage on the lonely shore of Baldoyle, well outside Dublin. However, this is the crusty old Irish peasant's first appearance in the narrative pictorial sequence. Despite his difficult and vigorous nature, Phiz shows the senior Dunn as bent-backed, balding, and skeletal. Phiz presents him as a binary opposite to his thoughtful son; whereas the old man with the nutcracker face stands as he studies his glass of wine, the seated son, much more elegantly dressed, smiles as he considers his future roles as "the Right Honourable Lord Castledunn" (538) and the husband of the clever, beautiful Lady Augusta. The clock on the wall suggests the lateness of the hour, but there will be no leisurely visit back to his boyhood roots for Davenport Dunn, who must be on the train for Belfast the next morning. Charles Lever has supplied the wine over which they toast Davy's future, but Phiz has furnished the room in homely style with no paintings, an unpretentious settle, and a well padded, cushioned chair for an elderly man with back and knee problems, and a fur throw in the centre. The objects beside the junior Dunn appear to be his luggage, but Phiz has the following description in mind: "Several baskets and hampers, carefully corded and sealed, were ranged beside the dresser, in which Dunn recognized presents of wine, choice cordials and liqueurs, that he had himself addressed to the old man" (537). Although Phiz makes the pair look congenial in each other's company, old Matthew Dunn voices discontent with his son's choice of bride (who the son had mentioned earlier, and whom the old man has almost immediately forgotten), momentarily casting a pall on their relationship.

Dunn confides to his father that his elevation to the British aristocracy will occur immediately after forthcoming parliamentary elections, in which as the leading Irish politico he will play a leading part: "Parliament will assemble after the elections, and then be prorogued; immediately afterwards there will be four elevations to the peerage, — mine one of them." Writing this instalment of the novel in 1858, Lever would have expected his readers to know that no general election occurred in 1855; rather, when the Aberdeen Whig-Peelite coalition government collapsed at the end of January 1855, Viscount Palmerston succeeded Aberdeen as Prime Minister and remained in power until after the close of the Crimean War. Effectively, the end of the war must have seemed imminent as early as the spring of 1855, but the collapse of the Vienna peace talks led to another round of fighting, which concluded with the fall of Sebastopol and the Battle of Inkerman (5 November 1854). The victorious Allies forced Russia to sue for peace, and sign the Treaty of Paris in March 1856. The plot of the novel in the summer of 1855 hinges on financial uncertainty attendant upon the collapse of peace talks in Vienna on 4 June 1855. Thus, Dunn thinks that the government and several significant private investors are supporting his western Ireland real estate development scheme:

“Well, sir, last week was a very threatening one for us. No money to be had on any terms, discounts all suspended, shares failing everywhere, good houses crashing on all sides, nothing but disasters with every post; but we 've worked through it, sir. Glumthal behaved well, though at the very last minute; and Lord Glengariff, too, deposited all his title-deeds at Hanbridge's for a loan of thirty-six thousand; and then, as Downing Street also stood to us, we weathered the gale; but it was close work, father, — so close at one moment I telegraphed to Liverpool to secure a berth in the Arctic.'” [537]

Dunn mistakenly assumes that the government will fall and rise again with his assistance. However, Lever's readers would have known not only that no elections ensued, but also that John Sadleir (the historical counterpart of Davenport Dunn) committed suicide on 17 February 1856 when his financial empire unravelled. The illustration misleads readers as to he outcome of Dunn's machinations; moreover, just before the scene realised, father and son argue over Davy's forgetting how badly the Glengariff family treated him as a youth, and subsequently argue over Davenport's plans to marry Lady Augusta.

“What 's her fortune, Davy? She ought to bring you a good fortune.”

“Say rather, sir, it is I that should make a splendid settlement, — so proud a connection should meet its suitable acknowledgment.”

“I understand little about them things, Davy; but there's one thing I do know, there never was the woman born I'd make independent of me if she was my wife. It isn't in nature, and it isn't in reason.”

“I can only say, sir, that with your principles you would not marry into the peerage.”

“Maybe I 'd find one would suit me as well elsewhere.”

“That is very possible, sir,” was the dry reply.

“And if she cost less, maybe she'd wear as well,” said the old man, peevishly; “but I suppose your Lordship knows best what suits your Lordship's station.”

“That also is possible, sir,” said Dunn, coldly.

The old man's brow darkened, he pushed his glass from him, and looked offended and displeased. [pp. 538-39]

Even as Dunn muses by his father's fireplace in Phiz's illustration that he will achieve a much-desired apotheosis by marrying Lady Augusta Arden and assuming a peerage as Lord Castledunn in exchange for political favours, his schemnes must suddenly unravel. However, he never breathes a word of unease to his adoring but crotchety father, who regards his son as a modern Irish Napoleon, a patriot of genius and daring.

Related Material: The Crimean War

- The Crimean War: "Britain in Blunderland"

- The Crimean War: Visual Materials

- Frontispiece (April 1859)

- "A Friend of Jack's" (October 1857)

- The Pony Race (October 1857)

- Catching a Colonel (September 1858)

- Charley the Smasher (March 1859)

- The Vision (April 1859)

Related Material: Financial Scandals

Scanned image by Simon Cooke; colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.] Click on the image to enlarge it.

Bibliography

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: The Man of The Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, November 1858 (Part XVII).

Last modified 3 August 2019