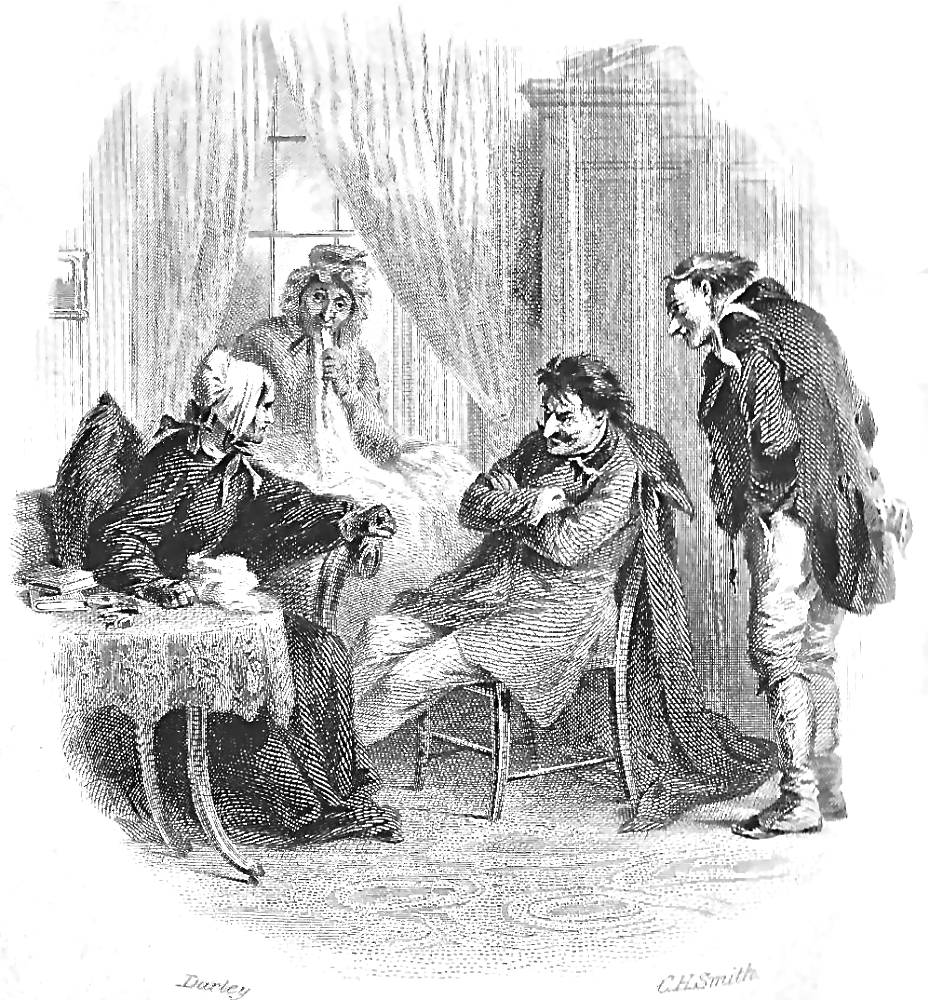

Damocles

Phiz (Hablot K. Browne)

June 1857

Illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Little Dorrit, Parts XIX-XX (Book 2, Chapter 30).

Source: Authentic Edition (1901), facing p. 676.

Passage Illustrated: “Less remarkable, now that she was not alone and it was darker, Mrs. Clennam hurried on at Little Dorrit's side, unmolested. They left the great thoroughfare at the turning by which she had entered it, and wound their way down among the silent, empty, cross-streets. Their feet were at the gateway, when there was a sudden noise like thunder.”

"What was that! Let us make haste in," cried Mrs. Clennam.

They were in the gateway. Little Dorrit, with a piercing cry, held her back. [Continued below]

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

[Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated

In one swift instant the old house was before them, with the man lying smoking in the window; another thundering sound, and it heaved, surged outward, opened asunder in fifty places, collapsed, and fell. Deafened by the noise, stifled, choked, and blinded by the dust, they hid their faces and stood rooted to the spot. The dust storm, driving between them and the placid sky, parted for a moment and showed them the stars. As they looked up, wildly crying for help, the great pile of chimneys, which was then alone left standing like a tower in a whirlwind, rocked, broke, and hailed itself down upon the heap of ruin, as if every tumbling fragment were intent on burying the crushed wretch deeper.

So blackened by the flying particles of rubbish as to be unrecognisable, they ran back from the gateway into the street, crying and shrieking. There, Mrs. Clennam dropped upon the stones; and she never from that hour moved so much as a finger again, or had the power to speak one word. For upwards of three years she reclined in a wheeled chair, looking attentively at those about her and appearing to understand what they said; but the rigid silence she had so long held was evermore enforced upon her, and except that she could move her eyes and faintly express a negative and affirmative with her head, she lived and died a statue.

Affery had been looking for them at the prison, and had caught sight of them at a distance on the bridge. She came up to receive her old mistress in her arms, to help to carry her into a neighbouring house, and to be faithful to her. The mystery of the noises was out now; Affery, like greater people, had always been right in her facts, and always wrong in the theories she deduced from them.

When the storm of dust had cleared away and the summer night was calm again, numbers of people choked up every avenue of access, and parties of diggers were formed to relieve one another in digging among the ruins. There had been a hundred people in the house at the time of its fall, there had been fifty, there had been fifteen, there had been two. Rumour finally settled the number at two; the foreigner and Mr. Flintwinch. — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 31, "Closed," p. 684-685.

Commentary

Damocles, as Michael Steig elaborates in Dickens and Phiz, Chapter 6, suggests the decaying atmosphere and moral collapse of the society Dickens describes, as well as Blandois-Rigaud's conception of himself as a cunning blackmailer and confidence man about to lower the blade of his victims, the guilt-ridden Mrs. Clennam, her confidential clerk, and her guileless son. However, the true meaning of the classical allusion here is its foreshadowing the collapse of the physical house of Clennam, a collapse which will engulf the would-be blackmailer himself, casually smoking in a window on the second storey:

In juxtaposition with its original companions, even the weakest of these four final Dorrit plates is effective. The first of the four, "Damocles" (Bk. 2, ch. 30; Illus. 113), is the last of the dark plates in any Dickens novel, and one of the strongest. The caption (presumably by Dickens) has an obvious irony: while Blandois thinks of himself as holding the Damoclean sword of blackmail over Jeremiah Flintwinch and Mrs. Clennam, in fact a Damoclean sword (in the form of the collapsing building in whose window he nonchalantly perches) is about to descend upon him.

It is of special interest that Phiz includes such indications of the imminent collapse as the stone falling from the eaves and the mangy cat apparently fleeing the house, because the text contains no direct suggestion of what is about to happen (it is left until near the end of the next chapter) — although there has been much previous fuss by Affery about the strange noises in the house. It is thus one of those cases where the novelist left an important fact to be dealt with in the illustration, which thereafter will become an integral part of the novel. Here, the artist has also added details which link the scene and the Clennam house with themes in Bleak House: the crude supports holding up the house remind one of "Tom all alone's," and hint at a connection between the middle-class acquisitive work-ethic of Mrs. Clennam and the disease-ridden slum which is "in" Chancery. [Steig, 171]

The story which begins in the prison at Marseilles "thirty years ago" (i.e., c. 1826) ends near the present, with Clennam's fortune engulfed in the collapse of Merdle's financial empire, a house of cards akin to the dilapidated Clennam mansion. Here, at the bottom of the picture, we see the portico with its rounded arch supported by pensive caryatids, as in Mr. Flintwinch has a mild Attack of Irritability in Part IX (Book 1, Chapter 30).

Although the illustration may pressage the collapse of Rigaud's plans along with the old house in Chapter 31, "Closed," it may also be a realisation of the moment at the very end of Chapter 30, "Closing In," when Rigaud believes that he has triumphed:

In the hour of his triumph, his moustache went up and his nose came down, as he ogled a great beam over his head with particular satisfaction. [678]

Rigaud-Blandois in the original, Diamond and two Household Editions, 1855-1910

Left: Phiz's realization of the scene between the Flintwinches and Blandois in the portico of the old house, Mr. Flintwinch has a mild Attack of Irritability (August 1856). Centre: Darley's 1863 frontispiece of the scene in which Blandois seems to be shutting confidence trap on his dupes, Closing Inn (Volume 4). Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's initial interpretation of the satanic Rigaud in prison, Rigaud and Cavalletto (1867). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: James Mahoney's Household Edition illustration of Affery, Jeremiah F lintwinch, the supremely self-confident Blandois, smoking a cigarette, and the dour Mrs. Clennam, In a moment Affery had thrown the stocking down, started up, caught hold of the windowsill with her right hand, lodged herself upon the window-seat with her right knee, and was flourishing her left hand, beating expected assailants off (Book II, Chapter 30). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

The Characters of Charles Dickens pourtrayed in a series of original watercolours by "Kyd." London, Paris, and New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, n. d.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1863. Vol. 4.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss [29 composite lithographs]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1919. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Victorian

Web

Little

Dorrit

Illus-

tration

Phiz

Next

Last modified 8 May 2016