In a moment Affery had thrown the stocking down, started up, caught hold of the windowsill with her right hand, lodged herself upon the window-seat with her right knee, and was flourishing her left hand, beating expected assailants off. — Book II, chap. 30. Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's fifty-fourth illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 10.5 cm high x 13.7 cm wide. Although the Chapman and Hall woodcut is identical to that to that in the New York (Harper and Brothers) edition, its caption is somewhat shorter: In a moment Affery had thrown the stocking down, started up, caught hold of the window-sill (See page 392.).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

Rigaud, thrusting Mr. Flintwinch aside, proceeded straight up-stairs. His two attendants followed him, Mr. Flintwinch followed them, and they all came trooping into Mrs. Clennam's quiet room. It was in its usual state; except that one of the windows was wide open, and Affery sat on its old-fashioned window-seat, mending a stocking. The usual articles were on the little table; the usual deadened fire was in the grate; the bed had its usual pall upon it; and the mistress of all sat on her black bier-like sofa, propped up by her black angular bolster that was like the headsman's block. Yet there was a nameless air of preparation in the room, as if it were strung up for an occasion. From what the room derived it — every one of its small variety of objects being in the fixed spot it had occupied for years — no one could have said without looking attentively at its mistress, and that, too, with a previous knowledge of her face. Although her unchanging black dress was in every plait precisely as of old, and her unchanging attitude was rigidly preserved, a very slight additional setting of her features and contraction of her gloomy forehead was so powerfully marked, that it marked everything about her.

"Who are these?" she said, wonderingly, as the two attendants entered. "What do these people want here?"

"Who are these, dear madame, is it?" returned Rigaud. "Faith, they are friends of your son the prisoner. And what do they want here, is it? Death, madame, I don't know. You will do well to ask them."

"You know you told us at the door, not to go yet," said Pancks.

"And you know you told me at the door, you didn't mean to go," retorted Rigaud. "In a word, madame, permit me to present two spies of the prisoner's — madmen, but spies. If you wish them to remain here during our little conversation, say the word. It is nothing to me." — Book Two, "Riches," Chapter 30, "Closing In," p. 391-392.

Commentary

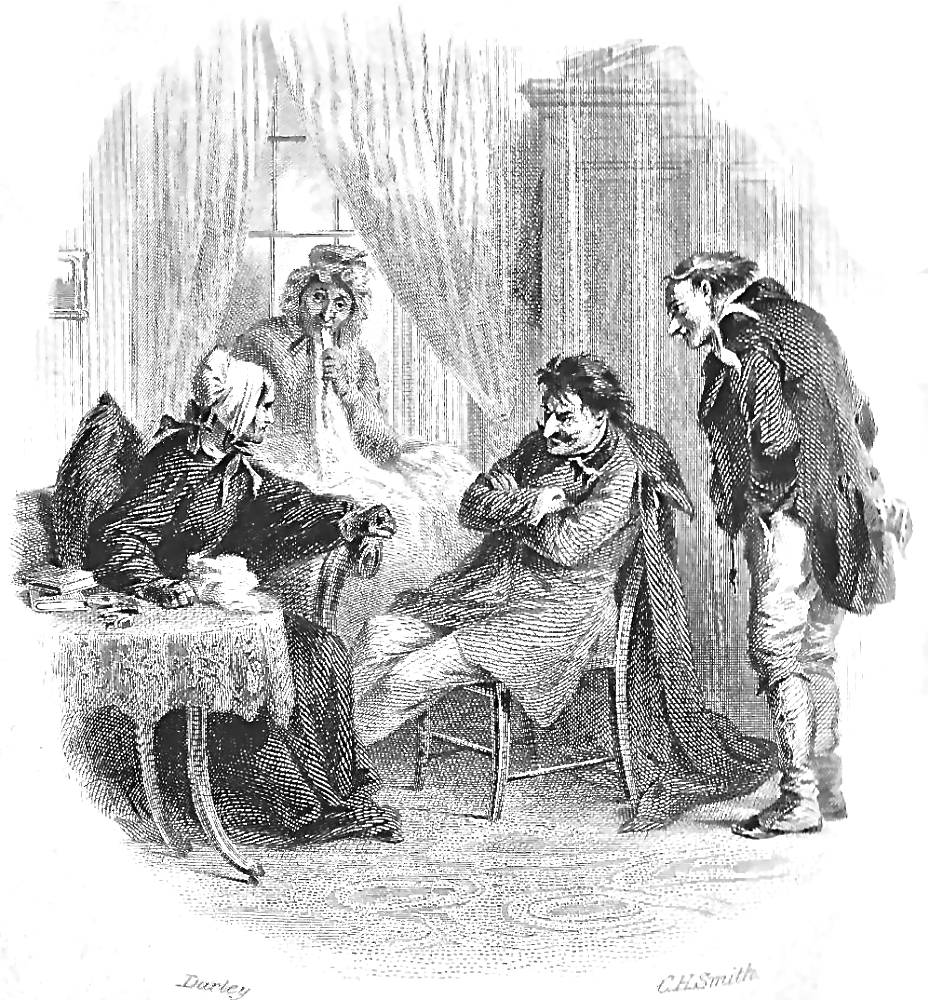

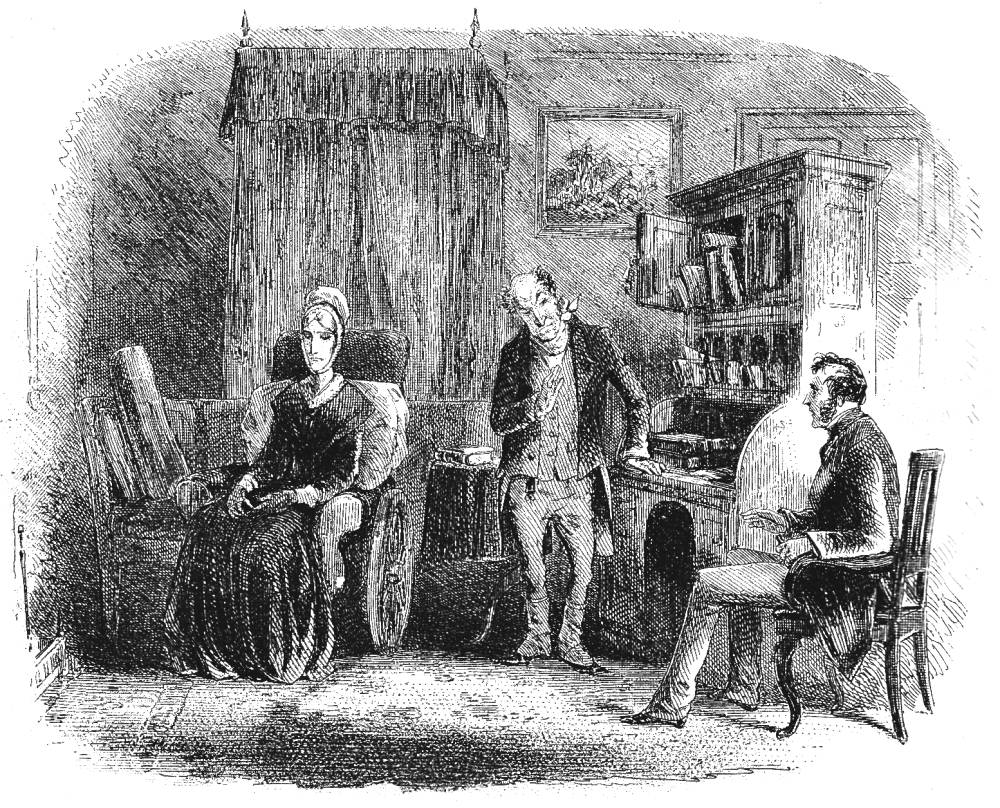

The scene is the matriarch's room in the Clennam townhouse at the culmination of the plot concerning her having suppressed the truth of Arthur's birth and the bequest to the Dorrits. In the original serial, the illustration for this chapter only obliquely alludes to Rigaud's blackmail plot, and does not show the dramatic confrontation between Flintwich, Rigaud (just right of centre here and in the F. O. C. Darley frontispiece,) and Mrs. Clennam. Phiz's June 1857 dark plate Damocles (Book Two, Chapter 30) realises the aftermath of the blackmail scene, when Rigaud, clinking his coins, believes he has Mrs. Clennam in his power, even though she has fled the house. However, Phiz's illustration completely obscures the figure of the cunning Frenchman,who will shortly perish in the collapse of the collapse of the decrepit mansion. Certainly, then, the confrontational scene that Darley and Mahoney elected to illustrate has no precedent in the original serial. James Mahoney's illustration for Book Two, Chapter 30, in the 1873 Household Edition volume shows Rigaud as entirely at his ease, even when Flintwich orders an overwrought Affery out of the room as Rigaud begins his blackmail narrative — and Affery, asserting herself at last, refuses: "I'll hear all I don't know, and say all I know. I will, at last, if I die for it. I will, I will, I will, I will!" In consequence of the dialogue realised, Mahoney has minimized the figure of Mrs. Clennam in the right-hand margin of this group illustration for Book Two, Chapter 30, but her sharpness makes her a match for the cunning Frenchman at this point.

The group scene, as in the earlier Phiz illustration set in that room, Mr. Flintwich mediates as a friend of the family, is Mrs. Clennam's upstairs parlour and bedroom. The characters depicted in the Mahoney wood-engraving are Monsieur Rigaud, the devious Frenchman to whom Dickens introduced us in the opening chapter; behind him, Mrs. Clennam; Flintwich, Mrs. Clennam's confidential servant (centre); and, making as if to climb out the window, Jeremiah Flintwich's wife, the habitually terrified maid Affery. The illustration makes it clear that Affery, like the reader, is about to receive a revellation.

Mrs. Clennam in the original, Diamond, and Household Editions, 1855-1867

Left: Darley's 1863 frontispiece of the same scene, again according Rigaud prominence, Closing In (Volume 4). Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's interpretation of the fanatical Mrs. Clennam and her adopted son, Arthur, Mrs. Clennam and Arthur Clennam (1867). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

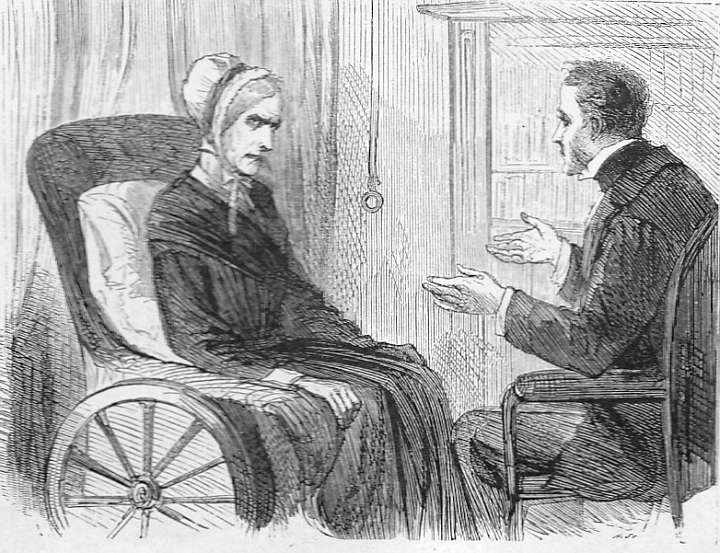

Above: Phiz's original serial illustration of Mrs. Clennam in her wheelchair, Mr. Flintwich mediates as a friend of the family (January 1856). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1863. Vol. 3.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss [29 composite lithographs]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1919. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 17 June 2016