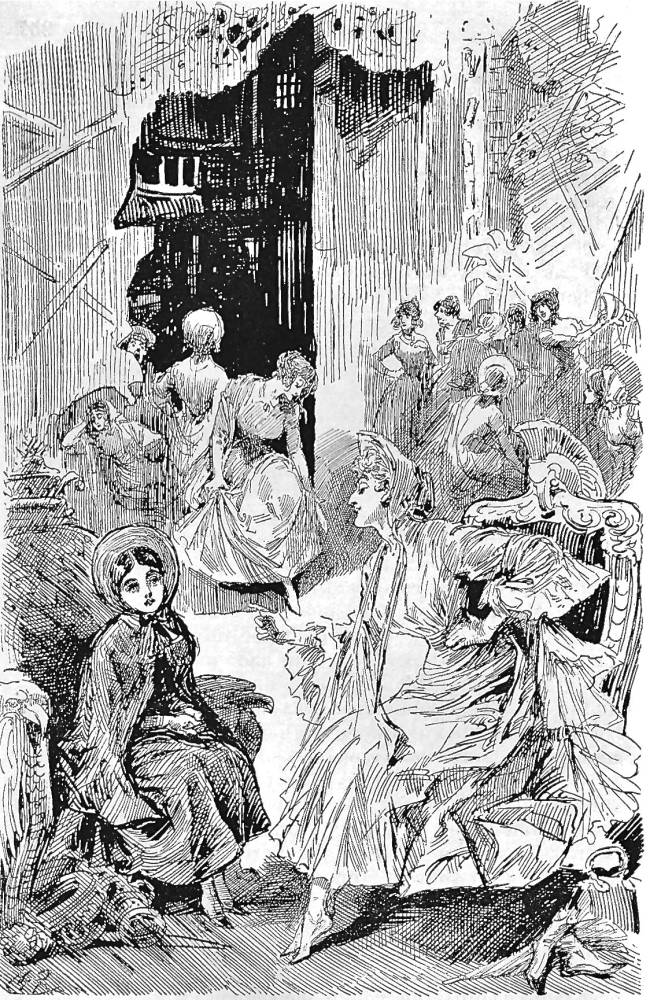

Miss Dorrit and Little Dorrit by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) from Dickens's Little Dorrit, Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 20, "Moving in Society" (May 1856: Part Six), facing p. 200. 10.5 cm high by 15.5 cm wide, vignetted. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

"Well! And what have you got on your mind, Amy? Of course you have got something on your mind about me?" said Fanny. She spoke as if her sister, between two and three years her junior, were her prejudiced grandmother.

"It is not much; but since you told me of the lady who gave you the bracelet, Fanny —"

The monotonous boy put his head round the beam on the left, and said, "Look out there, ladies!" and disappeared. The sprightly gentleman with the black hair as suddenly put his head round the beam on the right, and said, "Look out there, darlings!" and also disappeared. Thereupon all the young ladies rose and began shaking their skirts out behind.

"Well, Amy?" said Fanny, doing as the rest did; "what were you going to say?"

"Since you told me a lady had given you the bracelet you showed me, Fanny, I have not been quite easy on your account, and indeed want to know a little more if you will confide more to me."

"Now, ladies!" said the boy in the Scotch cap. "Now, darlings!" said the gentleman with the black hair. They were every one gone in a moment, and the music and the dancing feet were heard again.

Little Dorrit sat down in a golden chair, made quite giddy by these rapid interruptions. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 20, "Moving in Society," p. 201-202.

Commentary

In the original Phiz illustration for Chapter 20, "Moving in Society," Little Dorrit seems to sit in moral judgment of her actress sister, Fanny, backstage, after their visit to their uncle and to Mrs. Merdle. A more pertinent and interesting scene would have been that of the other stratum of society in which Fanny moves, that of the newly-rich Merdles of Harley Street, Cavendish Square, whom the sisters visit after the theatre. Phiz had to wait until the final double number in June 1857 to provide such illustration of the Dorrit sisters' entering the Harley Street mansion as the frontispiece, Fanny and Little Dorrit call on Mrs. Merdle. The backstage dialogue between the sisters accompanying the Phiz engraving conveys the stark differences between the older "experienced" Fanny, the "professional" dancer, and the somewhat isolated, child-like, virtuous Amy, her father's constant companion in the debtors' prison. Rarely out of the Marshalsea except to attend Mrs. Clennam, Amy is a complete stranger to this world that her sister and uncle inhabit, a world of tawdry realties and entertaining surfaces. Here we see the stage from behind the scenes as the sisters discuss Fanny's exploiting her relationship with Edmund Sparkler, the doltish son of the wealthy Mrs. Merdle.

The issue with which Phiz here and Harry Furniss in the Charles Dickens Library Edition's Little Dorrit among the Professionals (Book 1, Ch. 20) engage themselves is the jewelry and clothing that Fanny is extorting from Mrs. Merdle in exchange for not becoming romantically involved with her dull-witted, socialite son Edmund Sparkler. Amy is particularly concerned about a bracelet that Fanny now wears, and Fanny is equally concerned about the unsavoury reputation that theatrical people have acquired in respectable, upper-middle-class society — and about Amy's behaving as if they are paupers. Mrs. Merdle has objected to a match between her dissolute son and the daughter of an insolvent debtor (indeed, in chapter 20 of the first book she had actually bribed the young dancer to discourage her son's attentions), but subsequently withdraws her objection once the Dorrit family has come into a fortune. The Dorrit sisters discuss the issue of the bracelet when Amy is seated in a stage throne at the theatre in the Phiz original — the gilded chair in both the Phiz and Furniss illustrations suggesting moral authority and superior judgment. That Amy has not been sullied by the tawdry world of the Victorian stage will render her a suitable wife to Arthur Clennam at the end of the novel. Although the Furniss re-interpretation and the Phiz original have superficial similarities, including the backstage setting and the young dancers about to perform, significantly Furniss has shifted who is sitting on the throne, so that, in his pen-and-ink drawing, Fanny condescendingly treats Amy as if she were a senior, out of touch with reality. Amy is entranced (perhaps by this strange situation) rather than, as in Phiz, attentive and timid as she struggles to raise the issue of the bracelet. In the Mahoney illustration, we cannot see Amy's face, but her diminutive stature, in contrast to her sister's height, certainly suggests why she bears the nickname "Little Dorrit."

Relevant Illustrations of Amy and Fanny Dorrit from Other Editions, 1867-1910

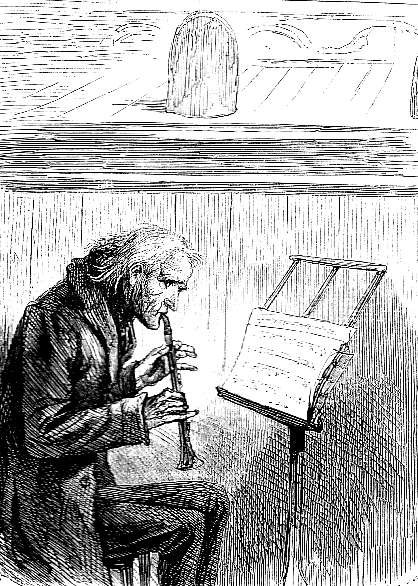

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's iluustration of the timid William playing his clarionet below the footlights, in the pit, William Dorri (1867). Right: Harry Furniss's updating of Phiz's May 1856 backstage scene, Little Dorrit among the Professionals (Book 1, Ch. 20). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: James Mahoney's illustration of another aspect of backstage society, When they arrived there, they found the old man practising his clarionet. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Phiz. The Authentic Edition. London:Chapman and Hall, 1901. (rpt. of the 1868 edition).

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 12 May 2016