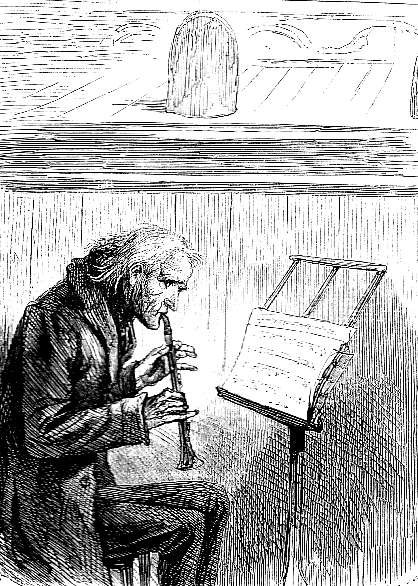

When they arrived there, they found the old man practising his clarionet. (See page 125.) — Book I, chap. 20, "Moving in Society," p. 121. Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's eighteenth illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 9.4 cm high x 13.7 cm wide.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

They spoke no more all the way back to the lodging where Fanny and her uncle lived. When they arrived there, they found the old man practising his clarionet in the dolefullest manner in a corner of the room. Fanny had a composite meal to make, of chops, and porter, and tea; and indignantly pretended to prepare it for herself, though her sister did all that in quiet reality. When at last Fanny sat down to eat and drink, she threw the table implements about and was angry with her bread, much as her father had been last night.

"If you despise me," she said, bursting into vehement tears, "because I am a dancer, why did you put me in the way of being one? It was your doing. You would have me stoop as low as the ground before this Mrs. Merdle, and let her say what she liked and do what she liked, and hold us all in contempt, and tell me so to my face. Because I am a dancer!"

"O Fanny!" — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 20, "Moving in Society," p. 125.

Commentary

The Chapman and Hall (British) Household Edition composite wood-engraving is identical to that in the New York (Harper and Brothers) edition; however, the American volume, in spite of its positioning the plate much closer to the text realized, has a much longer caption: They spoke no more, all the way back to the lodging where Fanny and her uncle lived. When they arrived there they found the old man practising his clarionet in the dolefullest manner in a corner of the room — Book 1, chap. xx.

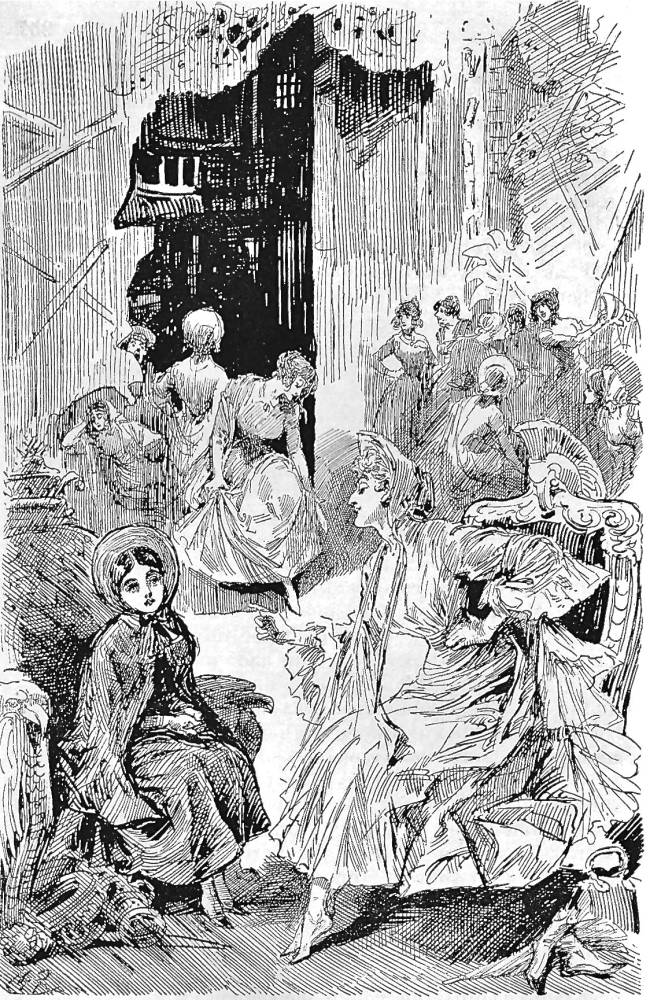

In the original serial illustrations, in the sixth monthly number (May 1856), Phiz depicts Little Dorrit and her older sister, Fanny, backstage at the theatre where Amy's sister is a professional dancer, a scene that is the basis for Harry Furniss's much later illustration, Little Dorrit among the Professionals. In avoiding these crowd scenes to focus on the three Dorrits in the little room which Fanny shares with her uncle, Mahoney has selected a subject lacking visual appeal, but has accurately characterized William Dorrit as a social isolate, unlike his gregarious brother, Frederick, the self-styled "Father of the Marshalsea."

Middle-class Attitudes towards "Theatre People"

Although Amy is the sister of a dancer, she is untainted by the early Victorian theatre and its tawdry denizens. This illustration, although realizing the moment when the sisters discover their uncle in his lodging, practising his instrument, the illustration is situated in an earlier part of the chapter, where Dickens describes William Dorrit as a musical drudge, eking out a living by playing six nights a week in the theatre, suggesting that the action of the early part of the book is set in the days before matinees:

The old man looked as if the remote high gallery windows, with their little strip of sky, might have been the point of his better fortunes, from which he had descended, until he had gradually sunk down below there to the bottom. He had been in that place six nights a week for many years, but had never been observed to raise his eyes above his music-book, and was confidently believed to have never seen a play. There were legends in the place that he did not so much as know the popular heroes and heroines by sight, and that the low comedian had 'mugged' at him in his richest manner fifty nights for a wager, and he had shown no trace of consciousness. The carpenters had a joke to the effect that he was dead without being aware of it; and the frequenters of the pit supposed him to pass his whole life, night and day, and Sunday and all, in the orchestra. They had tried him a few times with pinches of snuff offered over the rails, and he had always responded to this attention with a momentary waking up of manner that had the pale phantom of a gentleman in it: beyond this he never, on any occasion, had any other part in what was going on than the part written out for the clarionet; in private life, where there was no part for the clarionet, he had no part at all. — Book One, Chapter 20, p. 121.

In his portrait of William the clarionet player, Mahoney conveys the old musician's becoming so engrossed in his art that he is oblivious to the presence of his nieces, who have just arrived for dinner. A more pertinent and interesting scene would have been that of the other stratum of society in which Fanny moves, that of the newly-rich Merdles of Harley Street, Cavendish Square. The issue with which Phiz and Furniss engage themselves is the jewelry and clothing that Fanny is extorting from Mrs. Merdle in exchange for not becoming romantically involved with her dull-witted, socialite son Edmund Sparkler. Amy is particularly concerned about a bracelet that Fanny now wears, and Fanny is equally concerned about the unsavoury reputation that theatrical people have acquired in respectable, upper-middle-class society — and about Amy's behaving as if they are paupers. Mrs. Merdle has objected to a match between her dissolute son and the daughter of an insolvent debtor (indeed, in chapter 20 of the first book she had actually bribed the young dancer to discourage her son's attentions), but subsequently withdraws her objection once the Dorrit family has come into a fortune. The Dorrit sisters discuss the issue of the bracelet when Amy is seated in a stage throne at the theatre in the Phiz original — the gilded chair in both the Phiz and Furniss illustrations suggesting moral authority and superior judgment. That Amy has not been sullied by the tawdry world of the Victorian stage will render her a suitable wife to Arthur Clennam at the end of the novel. Although the Furniss re-interpretation and the Phiz original have superficial similarities, including the backstage setting and the young dancers about to perform, significantly Furniss has shifted who is sitting on the throne, so that, in his pen-and-ink drawing, Fanny condescendingly treats Amy as if she were a senior, out of touch with reality. Amy is entranced (perhaps by this strange situation) rather than, as in Phiz, attentive and timid as she struggles to raise the issue of the bracelet. In the Mahoney illustration, we cannot see Amy's face, but her diminutive stature, in contrast to her sister's height, certainly suggests why she bears the nickname "Little Dorrit."

Relevant Illustrations of Amy and Fanny Dorrit from Other Editions, 1856-1910

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's iluustration of the timid William playing his clarionet below the footlights, in the pit, William Dorri (1867). Right: Harry Furniss's updating of Phiz's May 1856 backstage scene, Little Dorrit among the Professionals (Book 1, Ch. 20). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: Phiz's original serial illustration of the Dorrit sisters backstage at the theatre where Fanny dances and William plays in the orchestra, Miss Dorrit and Little Dorrit (Book I, Ch. 20; May 1856). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.