"I entered into a long discourse" (See p. 155), signed "Wal Paget" just below Friday's knee, lower left. The centrally positioned illustration offers little context for the action (presumably Crusoe's fortress or cave), but establishes through Friday's posture, rapt facial expression, and gesture an engaging intimacy that Crusoe and Friday already enjoy. Friday's pointing upward complements the running head on page 155, "Rudiments of Religion," as it implies that he is enquiring about "the great Maker of all things" whom Crusoe describes as dwelling "beyond the sun" (155). Although Matt Somerville Morgan in the earlier Cassell's edition depicts Crusoe's spiritual enlightenment of his new servant in Crusoe instructing Friday, the earlier illustrator seems to have been is much more concerned with giving Crusoe a position of authority rather than graphing the growth of a friendship. One-third of page, vignetted: 7.5 cm high by 10.1 cm wide. Running head: "An Inquiring Pupil" (page 157).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated: The Education of the Noble Savage

From these things, I began to instruct him in the knowledge of the true God; I told him that the great Maker of all things lived up there, pointing up towards heaven; that He governed the world by the same power and providence by which He made it; that He was omnipotent, and could do everything for us, give everything to us, take everything from us; and thus, by degrees, I opened his eyes. He listened with great attention, and received with pleasure the notion of Jesus Christ being sent to redeem us; and of the manner of making our prayers to God, and His being able to hear us, even in heaven. He told me one day, that if our God could hear us, up beyond the sun, he must needs be a greater God than their Benamuckee, who lived but a little way off, and yet could not hear till they went up to the great mountains where he dwelt to speak to them. I asked him if ever he went thither to speak to him. He said, “No; they never went that were young men; none went thither but the old men,” whom he called their Oowokakee; that is, as I made him explain to me, their religious, or clergy; and that they went to say O (so he called saying prayers), and then came back and told them what Benamuckee said. By this I observed, that there is priestcraft even among the most blinded, ignorant pagans in the world; and the policy of making a secret of religion, in order to preserve the veneration of the people to the clergy, not only to be found in the Roman, but, perhaps, among all religions in the world, even among the most brutish and barbarous savages. [Chapter XV, "Friday's Education," p. 155]

Commentary

Paget establishes the precise textual passage realised through a caption that is a direct quotation from page 155, a source he has noted in his caption. Paget implies that the process of Europeanizing is in progress through the cloth breeches that Crusoe has given Friday, but that, as his nude torso suggests, the civilising is yet incomplete. In his hands Crusoe holds open a large seventeenth-century Bible salvaged from the original wreck. However, apparently Crusoe is not pointing to the story of creation in Genesis, but to Jesus Christ's sacrifice as "the Saviour of the world" (p. 157) in the Gospels. Friday seems genuinely interested in Crusoe's Presbyterian teaching, a scene which Paget embues with a delightful informality.

Since the reader encounters the illustration analeptically, he or she must mediate the passage illustrated two pages earlier with the present text, in which the "discourse" (157) with Crusoe as schoolmaster and the "poor savage" as pupil now turns towards the central tenets of Christianity, dispelling the native auditor's "ignorance" with "the light of the knowledge of God in Christ" in order to effect his spiritual salvation. For polytheist, Friday in Paget's illustration seems remarkably attentive to such monotheistic concepts as Crusoe references while reading from an enormous Bible.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Relevant illustrations from other nineteenth-century editions, 1790-1864

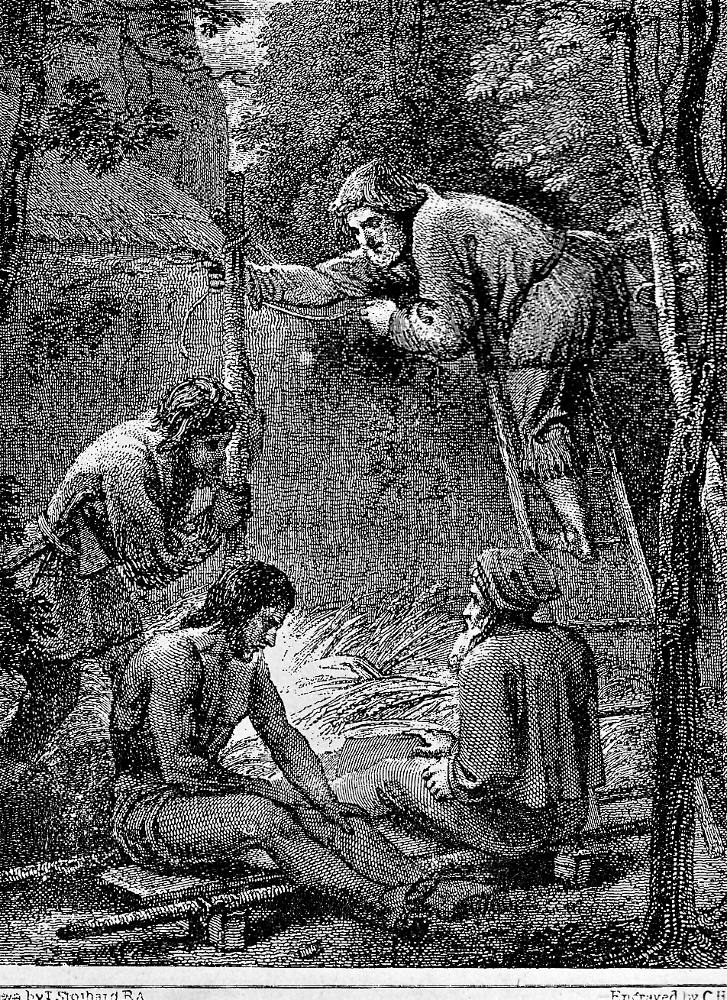

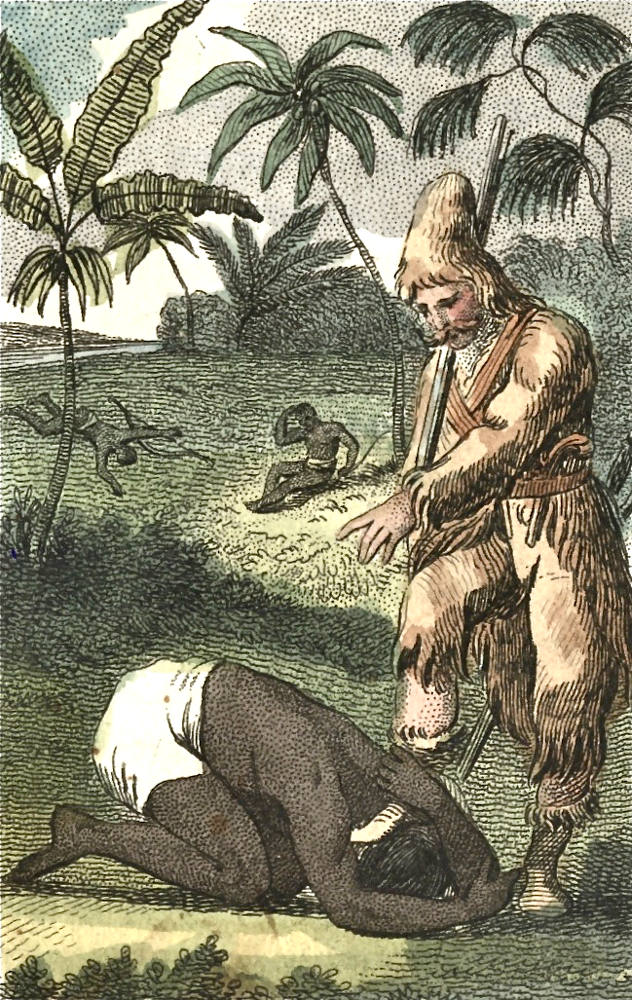

Left: The original Stothard copper-plate engraving in which Crusoe welcomes both former captives, the Spaniard and Friday's father (1790), Robinson Crusoe builds a tent for Friday's father and the Spaniard. Centre: Colourful realisation of the same scene, with a decidedly subservient and Negroid Friday contrasting the Caucasian Crusoe: Friday's first interview with Robinson Crusoe. (1818). Right: Matt Somerville Morgan's earlier realisation of Crusoe's conducting a catechism class for his new servant, Crusoe instructing Friday (1863-64). [Click on the illustrations to enlarge them.]

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 18 March 2018