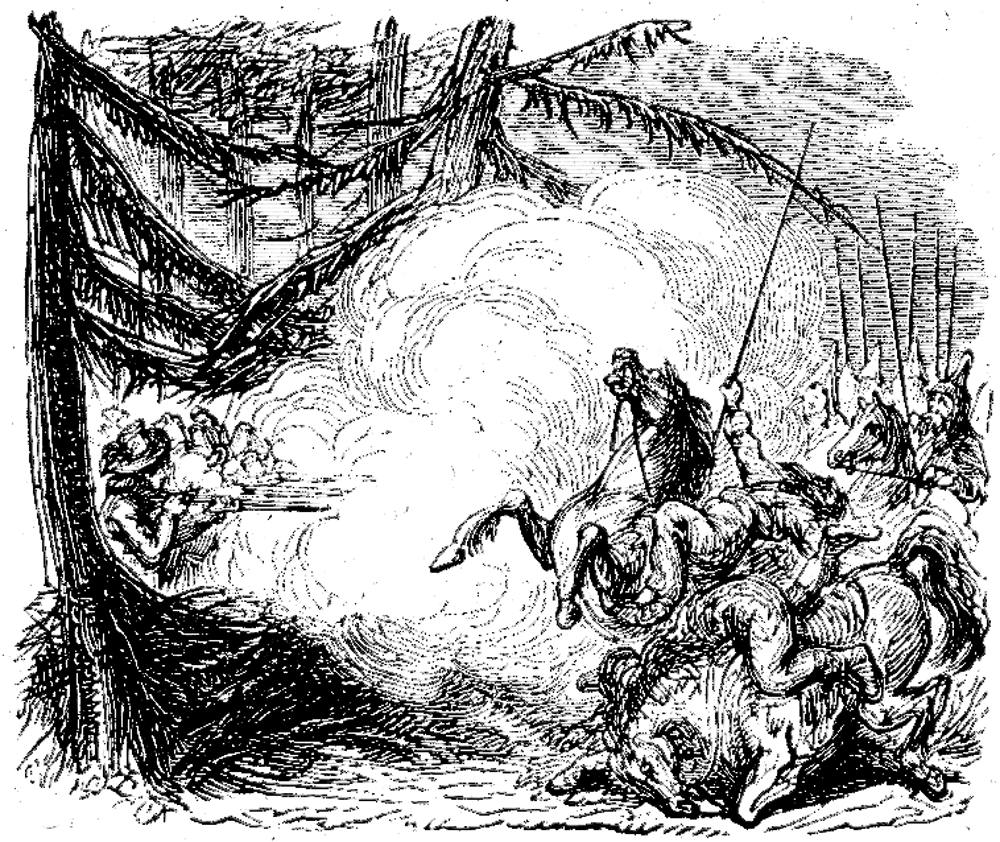

"Sent three messengers to us." (See p. 400), signed "Wal Paget" (lower right). Encamped in the Siberian wilderness, Crusoe's party survive an attack by a huge force of Tartar cavalry, but months later, having wintered in the Russian outpost of Tobolsk, Crusoe's diminished party faces the Tartars a final time after crossing back into Europe. One-third of page 403, centre, vignetted: 7 cm high by 12.2 cm wide. Running head: "In Siberia" (page 403).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: Three Tartars deliver a message under flag of truce

We observed they went away west, as we did, but had supposed we would have taken that side of the lake, whereas we very happily took the south side; and in two days more they disappeared again: for they, believing we were still before them, pushed on till they came to the Udda, a very great river when it passes farther north, but when we came to it we found it narrow and fordable.

The third day they had either found their mistake, or had intelligence of us, and came pouring in upon us towards dusk. We had, to our great satisfaction, just pitched upon a convenient place for our camp; for as we had just entered upon a desert above five hundred miles over, where we had no towns to lodge at, and, indeed, expected none but the city Jarawena, which we had yet two days’ march to; the desert, however, had some few woods in it on this side, and little rivers, which ran all into the great river Udda; it was in a narrow strait, between little but very thick woods, that we pitched our camp that night, expecting to be attacked before morning. As it was usual for the Mogul Tartars to go about in troops in that desert, so the caravans always fortify themselves every night against them, as against armies of robbers; and it was, therefore, no new thing to be pursued. But we had this night a most advantageous camp: for as we lay between two woods, with a little rivulet running just before our front, we could not be surrounded, or attacked any way but in our front or rear. We took care also to make our front as strong as we could, by placing our packs, with the camels and horses, all in a line, on the inside of the river, and felling some trees in our rear.

In this posture we encamped for the night; but the enemy was upon us before we had finished. They did not come on like thieves, as we expected, but sent three messengers to us, to demand the men to be delivered to them that had abused their priests and burned their idol, that they might burn them with fire; and upon this, they said, they would go away, and do us no further harm, otherwise they would destroy us all. Our men looked very blank at this message, and began to stare at one another to see who looked with the most guilt in their faces; but nobody was the word—nobody did it. The leader of the caravan sent word he was well assured that it was not done by any of our camp; that we were peaceful merchants, travelling on our business; that we had done no harm to them or to any one else; and that, therefore, they must look further for the enemies who had injured them, for we were not the people; so they desired them not to disturb us, for if they did we should defend ourselves. [Chapter XV, "Safe Arrival in England," pp. 400-401]

Commentary: Crusoe's Party brace for attack

Having destroyed the Tartars' idol, Crusoe discovers that his caravan is being pursued by ten thousand hostile horsemen who are bent on avenging the destruction of the sacred carving by the Christians (namely Crusoe and his Scots accomplices), but are not sure precisely who committed the sacrilege. At this point, it seems as if Crusoe is doomed as the numbers are not in his favour, even though he has an accompanying guard of two hundred Russian soldiers and the Tartars are armed with bows and spears rather than rifles. Defoe postpones the main battle with the Tartars, however, until June, after Crusoe and his party, now without their Russian troops, cross back into Europe after wintering at Tobolsk. Paget, with the benefit of a century of illustrated editions of the novel to consult, would certainly have seen George Cruikshank's depiction of this culminating episode in Crusoe's flight from the Tartars, The Europeans fire a withering volley at the charging Tartar horde in Russia (1831).

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Cruikshank's Scenes of Combat with the Tartars (1831)

Left: As Crusoe regains consciousness, he discovers that his companions have driven off the robbers in Crusoe, regaining consciousness, sees the dead Tartar. Right: Cruikshank's dramatic tailpiece for Farther Adventures: Crusoe and his partyy deliver a furious volley from behind a stockade of stacked tree trunks in The Europeans fire a withering volley at the charging Tartar horde in Russia. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

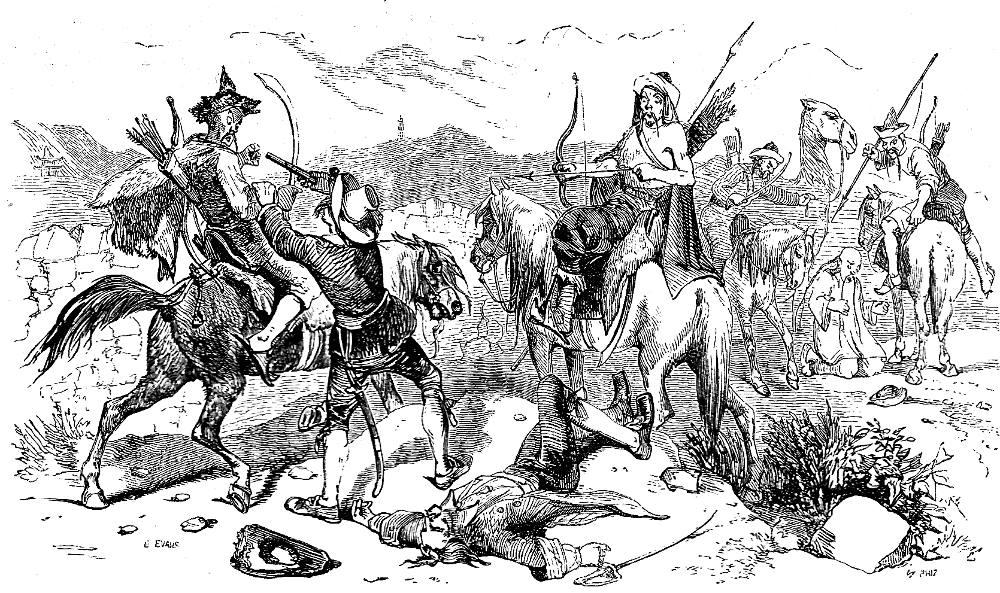

Phiz's Interpretation of the Tartars' Theft of the Camel (1864)

Above: Phiz's highly dramatic, full-page illustration of the Portuguese pilot's grabbing the Tartar, Robinson Crusoe attacked and robbed by Tartars. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

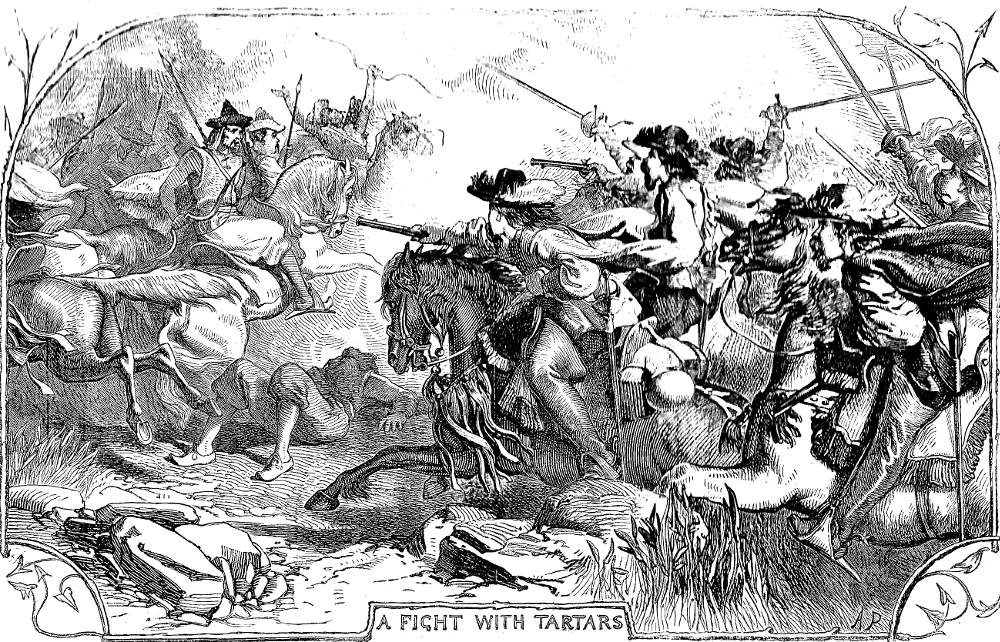

The Cassell's Interpretations of the Tartar Cavalry (1864)

Above: The Cassell's team produced a pair of highly dramatic, full-page illustrations for Crusoe's adventures in Tartary; particularly dynamic is A Fight with Tartars, in which the Europeans stage a daring charge. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Above: The second Cassell's full-page composite woodblock engraving shows the Tartars in full retreat as European weaponry results in casualties and fatalities on their side, but none on the other: Flight of the Tartars. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Stothard's and Cassell's Scenes involving the Tartars (1790, 1820; 1864)

Left: As Crusoe and his party cross Tartar territory, the wily horsemen shadow them in Stothard's Robinson Crusoe travelling in Chinese Tartary. Right: The 1864 Cassell edition's idyllic full-page realisation of the European encampment, about to be visited by the Tartar army, Crusoe and Party in Tartary. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

References

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Exciting Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner, as Related by Himself. With 120 original illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris,and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 17 April 2018