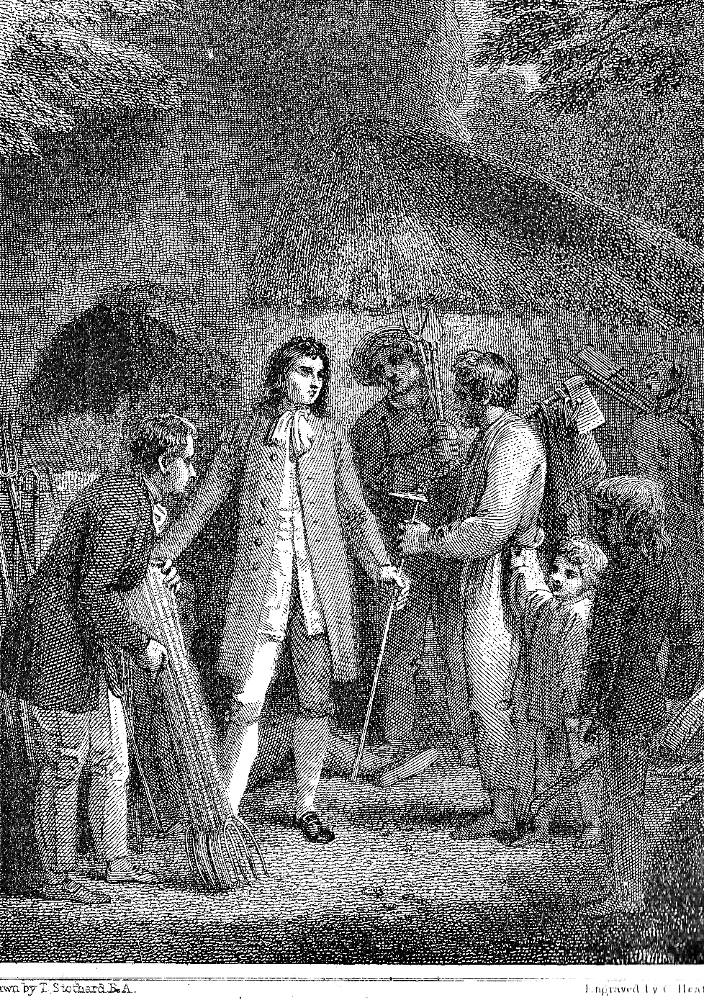

"I have brought you an assistant." (See p. 325), signed by Wal Paget, bottom left. Paget balances the colonist and his family with the figure of the elaborately dressed Crusoe as he presents Will Atkins with a Bible. Half of page 329, vignetted: 9 cm high by 13 cm wide. Running head: "The Young Man's Version" (page 329).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

It came next into my mind, in the morning before I went to them, that amongst all the needful things I had to leave with them I had not left them a Bible, in which I showed myself less considering for them than my good friend the widow was for me when she sent me the cargo of a hundred pounds from Lisbon, where she packed up three Bibles and a Prayer-book. However, the good woman’s charity had a greater extent than ever she imagined, for they were reserved for the comfort and instruction of those that made much better use of them than I had done.

I took one of the Bibles in my pocket, and when I came to Will Atkins's tent, or house, and found the young woman and Atkins’s baptized wife had been discoursing of religion together — for Will Atkins told it me with a great deal of joy — I asked if they were together now, and he said, "Yes"; so I went into the house, and he with me, and we found them together very earnest in discourse. "Oh, sir," says Will Atkins, "when God has sinners to reconcile to Himself, and aliens to bring home, He never wants a messenger; my wife has got a new instructor: I knew I was unworthy, as I was incapable of that work; that young woman has been sent hither from heaven — she is enough to convert a whole island of savages." The young woman blushed, and rose up to go away, but I desired her to sit-still; I told her she had a good work upon her hands, and I hoped God would bless her in it.

We talked a little, and I did not perceive that they had any book among them, though I did not ask; but I put my hand into my pocket, and pulled out my Bible. "Here," said I to Atkins, "I have brought you an assistant that perhaps you had not before." The man was so confounded that he was not able to speak for some time; but, recovering himself, he takes it with both his hands, and turning to his wife, "Here, my dear," says he, "did not I tell you our God, though He lives above, could hear what we have said? Here's the book I prayed for when you and I kneeled down under the bush; now God has heard us and sent it." When he had said so, the man fell into such passionate transports, that between the joy of having it, and giving God thanks for it, the tears ran down his face like a child that was crying. [Chapter VIII, "Sails from the Island for the Brazils," page 325]

Commentary

The scene occurs, as Crusoe explains, in the north-east quadrant of the island assigned to English colonists. The young European woman seated to the right, beside Mrs. Atkins, has been recently married to Crusoe's artisan, a Jack-of-all-Trades, whom Crusoe has brought with him to the island. Her presence in the text is easily overlooked, but Paget, perhaps modelling his lithograph on the wood-engraving correctly includes her, since she was in the house, discoursing with Mrs. Atkins on religious matters, when Crusoe arrived with the Bible — which should, however, be pocket-sized.

The prominence of the Bible in both parts of Robinson Crusoe undoubtedly reflects Defoe's Protestantism. However, a number of nineteenth-century illustrators have underscored the importance of scripture reading to Crusoe's moral life, as in George Cruikshank's "Jesus, . . . give me repentance", and both Cassell's editions show Crusoe delivering religious instruction to his new servant as a fundamental part of civilising the aboriginal.

Moreover, in the second half of the story among the provisions that Crusoe has brought to the island are several Bibles, intended to reinvigorate the Christian convictions of the young colonists. The presence of the printed book as the mechanism or technology of religious instruction, much more prevalent in British Protestant than European Catholic culture, is crucial to understanding Crusoe's motivation for returning to the island in The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. The Cassell's mid-nineteenth-century illustration of Crusoe's conducting religious instruction with Friday, his spiritual discussions with the French priest, and his presentation of the Bible to Atkins and his recently baptised native wife, may be an oblique allusions to British Victorian Bible societies and colonial missionary work in this period. Dickens in Bleak House (1851-53), on the other hand, seems to have found overseas Christian missions by British Bible societies a worthy subject of satire in the ridiculous figure of the philanthropic Mrs. Jellyby, who has devoted so much of her time to the spiritual welfare of the natives of Borrioboola-Gha on the banks of the Niger that she has totally neglected her own children.

Unlike the earlier Cassell illustrator, William Luson Thomas, Paget fails to contextualise the scene of Crusoe's presenting the Bible to Will Atkins as the women look on. This is the vigorous, fashionably dressed Crusoe rather than the elderly visitor seen in some of the 1864 illustrations, and one may well believe that the young planter who receives the gift in both hands was not that long ago a sailor, if one may judge by his clothing and head-covering. The text describes Atkins at this moment as "so confounded, that he was not able to speak" (p. 325), but Paget's young husband does not seem to be speechless — nor is he as surprised as Will Atkins in the 1864 illustration "Crusoe gives Atkins a Bible". Whereas Mrs. Atkins is a tall, long-haired young woman of obviously aboriginal heritage in the earlier illustration, as one might expect, given Crusoe's description of her as "the newly-baptised savage woman" (p. 325), here and elsewhere in Paget's series, although "tawny" (p. 310), her features do not appear to be aboriginal, but are certainly consistent with those of the tribesmen whom Paget has depicted in "Indians just coming on shore", "Came ranging along the shore", and "Despatched these poor creatures", all of which suggest that Paget conceives of the natives of the region as African.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Relevant illustrations from other 19th editions, 1820-1864

Left: The Wehnert engraving of the same scene, Crusoe giving Bible to Will Atkins (1862). Centre: The 1864 Cassell edition's realistic wood-engraving of the same scene, Crusoe gives Atkins a Bible (1864). Right: The original Stothard scene of Crusoe's return, Robinson Crusoe distributing tools of husbandry among the inhabitants (1820). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: Cruikshank's realisation of Crusoe's visiting Will and his wife, Crusoe presents a Bible to Will Atkins and his native wife (1831). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

References

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Exciting Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner, as Related by Himself. With 120 original illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris,and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 2 April 2018