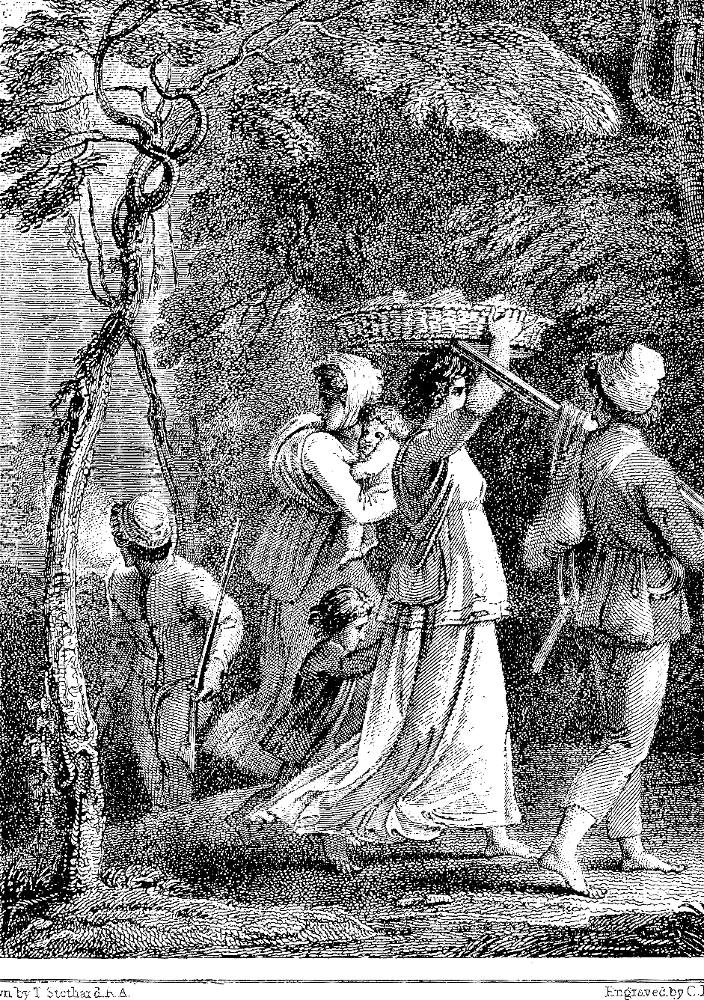

All their huts and household stuff flaming up together. (See p. 273), signed by Wal Paget, bottom right. Paget has described the destruction of the plantation from the perspective of the two colonists in the foreground. The dramatic escape of the settlers and their wives in Thomas Stothard's elegant series of illustrations, The two Englishmen retreating with their wives and children, may have flagged the moment for Paget, who had probably seen the earlier narrative-pictorial sequence. One-half of page 277, framed: 9 cm high by 12.5 cm wide. Running head: "Ruin" (page 277).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated: The Plantation of the Two Honest Englishmen Destroyed

In the next place, seeing the savages were all come on shore, and that they had bent their course directly that way, they opened the fences where the milch cows were kept, and drove them all out; leaving their goats to straggle in the woods, whither they pleased, that the savages might think they were all bred wild; but the rogue who came with them was too cunning for that, and gave them an account of it all, for they went directly to the place.

When the two poor frightened men had secured their wives and goods, they sent the other slave they had of the three who came with the women, and who was at their place by accident, away to the Spaniards with all speed, to give them the alarm, and desire speedy help, and, in the meantime, they took their arms and what ammunition they had, and retreated towards the place in the wood where their wives were sent; keeping at a distance, yet so that they might see, if possible, which way the savages took. They had not gone far but that from a rising ground they could see the little army of their enemies come on directly to their habitation, and, in a moment more, could see all their huts and household stuff flaming up together, to their great grief and mortification; for this was a great loss to them, irretrievable, indeed, for some time. They kept their station for a while, till they found the savages, like wild beasts, spread themselves all over the place, rummaging every way, and every place they could think of, in search of prey; and in particular for the people, of whom now it plainly appeared they had intelligence. [Chapter IV, "Renewed Invasion of the Savages,"page 273]

Commentary

Paget suggests by the feathered hat that Will Atkins is the colonist to the right, readily identifiable by his feathered hat; however, this is the plantation of the English colonists that the invaders (led by the escaped native whom the Spanish spared) have torched, and not the Atkins plantation. The destruction of the settlers' property prompts Crusoe to commiserate with them over their "being now twice ruined, and all their improvements destroyed" (p. 277: the same page on which the illustration of the actual destruction occurs). The cannibals' immolation of the European settlement sets them up for annihilation in the subsequent action, and the illustration certainly functions to engage the readers' sympathies for the two men who watch the products of their labour go up in flames. The alternative perspective, namely that the Europeans are encroaching upon traditional aboriginal territory, is never presented since, as Defoe had said on a number of occasions in Part One, this is a "deserted" or deserted island which the cannibals from the mainland opposite use only for the occasional feast.

In the earlier copperplate illustration, The two Englishmen retreating with their wives and children (1790), the group of survivors (not just the two colonists, but also the women and children) move forward, left to right, in a dignified silence, aware that they are being pursued, but not showing evidence of panic or undue haste. If we compare Paget's treatment of the theme to Stothard's, we find that the 1891 lithograph is focussing not on the escape of the planters and their families, but on the wanton destruction of property, which, both distraught and fascinated, they watch from the edge of the meadow.

In Part One, Crusoe originally had no intention of interfering in the cannibals' second grisly feast as long as they would leave him alone. However, when Crusoe realizes that one of the victims is bearded, he concludes that he must intervene to preserve the life of a "Christian." However, such intervention may expose him to considerable danger, both in the actual battle to liberate the Spanish captive, in which he and Friday are badly outnumbered, and afterwards, should any of the cannibals escape to return later to take revenge on Crusoe. That same pattern of instability of Crusoe's situation in Part One repeats itself in Part Two when one of the captured natives escapes from the plantation of the two "honest" Englishmen and reports to his fellows on the mainland that a small contingent of Europeans has colonized the island. The result, once again, is an invasion, followed by the Europeans' defeating the aboriginals.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Related Plate from the 1864 Cassell Edition

Above: The earlier Cassell edition's realistic wood-engraving of the Englishmen returning to their families after binding one of the native captives to a tree, The Englishmen bind the Savage to a Tree. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 6 April 2018