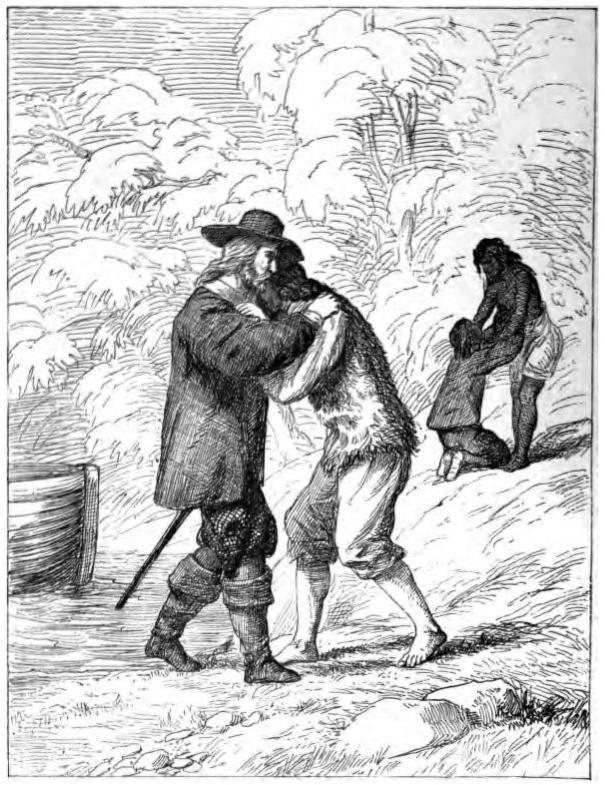

"Do you not know me?"

Wal Paget (1863-1935)

lithograph

18 cm high by 12.9 cm wide, framed.

1891

Robinson Crusoe, facing page 242.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated: Crusoe returns to the Island

But this is a digression: I return to my landing. It would be needless to take notice of all the ceremonies and civilities that the Spaniards received me with. The first Spaniard, whom, as I said, I knew very well, was he whose life I had saved. He came towards the boat, attended by one more, carrying a flag of truce also; and he not only did not know me at first, but he had no thoughts, no notion of its being me that was come, till I spoke to him. “Seignior,” said I, in Portuguese, “do you not know me?” At which he spoke not a word, but giving his musket to the man that was with him, threw his arms abroad, saying something in Spanish that I did not perfectly hear, came forward and embraced me, telling me he was inexcusable not to know that face again that he had once seen, as of an angel from heaven sent to save his life; he said abundance of very handsome things, as a well-bred Spaniard always knows how, and then, beckoning to the person that attended him, bade him go and call out his comrades. He then asked me if I would walk to my old habitation, where he would give me possession of my own house again, and where I should see they had made but mean improvements. I walked along with him, but, alas! I could no more find the place than if I had never been there; for they had planted so many trees, and placed them in such a position, so thick and close to one another, and in ten years’ time they were grown so big, that the place was inaccessible, except by such windings and blind ways as they themselves only, who made them, could find. [Chapter II, "Intervening History of the Island," page 241]

Commentary

In the lengthier programs of illustration across the nineteenth century artists have realised the return of the absent Governor, sixty-one-year-old Robinson Crusoe, to the island south of Trinidad and east of the mouth of the Orinoco — apparently administered jointly by those old enemies, Spain and Britain. George Cruikshank in 1831 realised the joyful reunion of Friday and his father, and Edward Henry Wehnert in 1862 included Friday and his father in the background of Crusoe's Second Landing on the Island. Wehnert's title underscores the very different manner in which the former castaway arrives, now honoured by the thriving European colony. Whereas Cruikshank enjoys an emotional scene that lends itself to lively caricature, Stothard embues the return with dignified solemnity, and Wehnert with the overflowing emotion of male bonding. Paget, too, sees the moment as signifying Crusoe's welcome by a group or community. The Cassell illustrator, Matt Somerville Morgan, however, depicts two contrasting figures: a shaggy, roughly dressed Spaniard, obviously delighted to see his former comrade again, and a tall, well-dressed Crusoe, now representing the power of the Mother Country. In the background, several of Crusoe's crew watch the proceedings from the longboat with interest.

Paget has adapted and altered the 1864 illustration significantly. Here, the returning Governor, dressed in heavy clothing unsuited to the tropics, formally removes his hat, and the leader of the Spanish colonists leans back ever so slightly, as if unsure of the identity and intentions of this well-dressed Englishman (his nationality proclaimed by the flags on his ship in the distance). The moment of recognition has yet to occur on the part of the Spaniard. Although mere colonials in a tropical environment, the two Spaniards are well dressed, too, and do not resemble to rough-clad ragamuffin of the 1864 illustration. Finally, Paget has placed footprints in the sand, not merely as realistic details but as reminders of the emotional events that led to Crusoe's rescuing the Spaniard from the cannibals, in particular "I stood like one thunderstruck.".

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Parallel Scenes from Stothard (1790), Cruikshank (1831), Wehnert (1862), and Cassell (1864)

Left: Thomas Stothard's tranquil study of Crusoe's returning to the island, Robinson Crusoe's first interview with the Spaniards. Centre: E. H. Wehnert's doubly emotional reunion, of the Spaniard and Crusoe and of Friday and his father: Crusoe 's Second Landing on the Island. Right: Matt Somerville Morgan's parallel scene, a large-scale realisation of the heartfelt welcoming that an elegantly dressed Crusoe receives, Crusoe welcomed by the Spaniard (1864). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Cruikshank's small-scale realisation of the meeting on the beach of the long-absent son and the aged parent, Friday and his Father (1831).

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustra-

tion

Walter

Paget

Next

Last modified 26 March 2018