Introduction: North as an illustrator

Like many of his contemporaries, John William North (1841–1924) supported his work as a painter by producing illustrations for books and magazines. These were exclusively published in the form of wood-engravings, appearing in journals such as The Sunday Magazine, Good Words and Once a Week. They also featured in a variety of gift books, notably in A Round of Days(1866) and Wayside Posies (1867).

North specialized in landscape and rural subjects, a type of imagery that appealed to a large and mainly urban audience. However, his treatments of country themes are far from orthodox. In contrast to Birket Foster, whose pastoral scenes are unremittingly idealistic and deploy a limited range of compositions and motifs, North’s drawings on wood are both inventive and challenging.

North, Idyllic imagery and social observation

North is usually classified as a member of the ‘Idyllic School’ (Reid, p.134), sharing this designation with Frederick Walker, Robert Barnes, John Dawson Watson, and George Pinwell. Yet definition of this term is itself problematic, and in order to place this artist it is necessary first of all to consider the principal features of the ‘idyllic’ style. Derived from the title of Idyllic Pictures (1867), and in common usage by the end of the nineteenth century, the terms ‘Idyllic’ or ‘the Idyllic manner’ embraced a number of common features. Goldman argues that artists working in this idiom were not

interested in a ‘remote past’, a dreamy medieval world peopled from knights, swooning mistresses and tales of legend, which the Pre-Raphaelites perfected. Instead they created scenes which were more earthbound but, at their best, were no less poetic or intense. They often depicted a harmonious rural life with decent but poor people apparently leading simple, noble existences far from urban squalor [p.115].

He goes on to note how their work invariably presents ‘a strong moral and religious feeling’ (p.116), although it was not concerned with ‘social issues’ (p.115). Goldman’s comments are useful, and we can define North as an ‘Idyllic artist’ insofar as he was centrally concerned with the lives of the rural poor while reflecting on the narrowness of their lives; this interest is undoubtedly ‘moral and religious’ in tone. Yet it could not be said that he avoided the social questions that are raised, as it were, by the moral ones. On the contrary, his art embraces both idealism and realism: he shows the English landscape with Romantic intensity, but he also depicts some of the privations of those working the soil. This ambivalence resonates throughout his designs.

North is at his most pleasing, as the ‘conscientious’ practitioner of a ‘sincere’ and ‘delicate’ art (Reid, p.163), in illustrations such as The Home Pond in A Round of Days. This focuses on the harmonies of landscapes and figures, constructing a notion of the English idyll that is clearly based on observation.

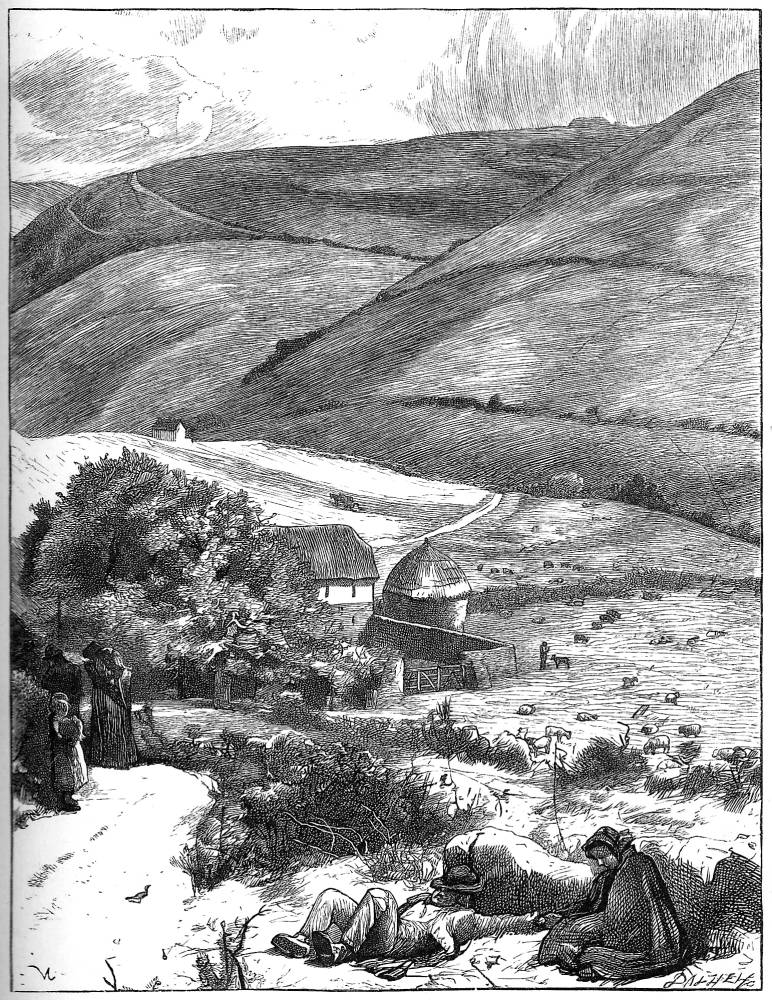

Left to right: (a) Glen Oona. (b) The Visions of a City Tree. (c) Spring [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

The Visions of a City Tree in Wayside Posiesis similarly presented as a vision of the beautiful English landscape which is based on an unconventional view, with a large tree placed as the focus, a high perspective and the figures moved to the absolute foreground. Spring (Wayside Posies) is likewise an unexpected combination of everyday motifs and an unusual viewpoint; the building to the right is half-edited out of the frame, while pollarded trees map the centre-ground.

Indeed, all of his landscapes display a sensitivity to unusual views and compositions. In contrast to Myles Birket Foster, he avoids the stereotypical properties of the Picturesque and presents a fresh vision, essentially moments of insight where the commonplace is rediscovered. These scenes are transformed into a new version of natural beauty where toil imposes itself on the land. The working landscape becomes an Arcadia that is recognisably England, rather than an idea of England.

North's revisionism also embraces views of a wild and wasted landscape, the country that falls outside the practices of agriculture. His illustrations to Jean Ingelow’s ‘Four bridges’ reveal a desolate series of spaces, an interest developed in The Heath and Autumnal Song (Wayside Posies), where emptiness is the subject, and nature returns to a primal state. Though produced in the 1860s, these images anticipate the wrecked landscapes described by Richard Jefferies in his apocalyptic vision of the future, After London (1885); interestingly, North and Jefferies met in 1883 and seem to have shared a sometimes pessimistic view of the natural world.

What is perhaps more unusual is the fact that North published images of an England gone to waste in the setting of conventional gift books, which were never intended to unsettle or challenge. Working in this context, he is even more outspoken in his visualization of country life, showing it in a way which is far from idealised or stereotypical. Of working-class origin, North is sympathetic to the sufferings of the rural labouring class and like George Pinwell – who was an associate – regularly shows the hard facts of poverty. This situation is sometimes depicted in terms of the anonymity of a class of people who are quite literally extensions of nature and absorbed into the process of working the land, just as factory workers are extensions of the machinery. In Reaping, for instance, we see the workmen reduced to types, cutting their way to the foreground where rabbits crouch in terror. This is an image of traditional activity while figuring as an emblematic sign of the anonymous poem’s grim conclusion: everyone is ‘reaped by the hand of a Reaper’ (Wayside Posies, p.31).

The use of visual metaphor is similarly deployed in At the Grindstone, which carries the implication that the grinding of the stone is symbolically grinding the lives of the ordinary people. Surrounded by emblems of decay in the form of a rotten tree dropping branches, an overgrown farm-yard and an ominous crow, the characters shown in this design are again faceless peasants and quite unlike the idealised figures populating the art of Birket Foster.

This imagery constitutes a generic commentary, pointing to the fact that country folk of the mid nineteenth century are still essentially peasants in a culture that is yet to become a democracy in the sense of full suffrage, and whose interests are not represented. North especially explores homelessness and vagrancy, problematizing the viewer’s response by combining the idyll, the emblem of plenty, with privation. In Glen Oona (Wayside Posies), he combines the lush sweep of the glen with a small detail of two figures in the right foreground. These are an exhausted man and wife, looking, in all likelihood, for work. This information is not given in the accompanying poem, and North characteristically extends the range and implication of his literary source. As noted earlier, this approach recalls Pinwell’s designs, and both artists present a social commentary which, although contained in rural imagery, is remarkably direct. ‘Idyllic’ North may have been, but his imagery embodies a social commentary that is both compassionate and angry, prefiguring the observations that appear in The Graphic in the 1870s.

Related material

- Social Commentary and Victorian Illustration: The Representation of Working Class Life, 1837–1880

- Social Commentaries of the 1860s: from Dickens to the Idyllic School of Illustration

Works Cited

Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustration. Aldershot: Scolar, 1996; Lund Humphries, 2004.

Idyllic Pictures. London: Cassell, Petter, & Galpin, 1867.

Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Sixties. London: Faber & Gwyer, 1928; rpt. New York: Dover, 1975.

Round of Days, A. London: Routledge, 1866.

Wayside Posies. Ed. Robert Buchanan. London: Routledge, 1867.

Last modified 26 April 2019