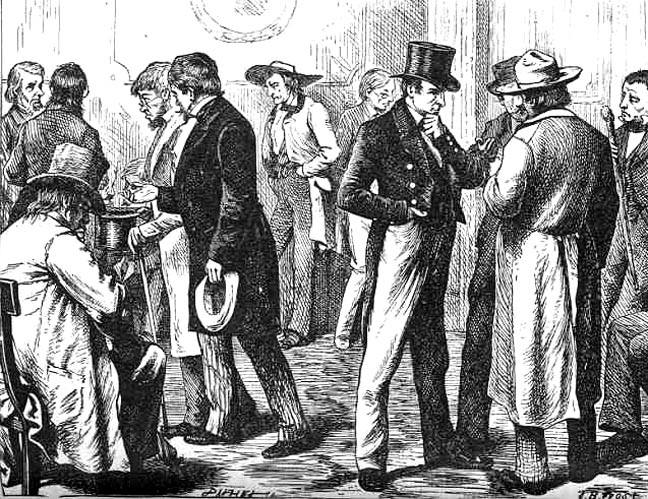

The National Spittoon by Thomas Nast, in Charles Dickens's Pictures from Italy and American Notes (1877), Chapter VIII, "Washington. — The Legislature. — The President's House," p. 329. Wood-engraving, 4 by 5 ⅜ inches (10.3 cm high by 13.5 cm wide), vignetted. Descriptive headline: "The Insolence of Some English Settlers" (329).

Passage Illustrated: Dickens's Disgust at American Chewing and Spitting of Tobacco

As Washington may be called the head-quarters of tobacco-tinctured saliva, the time is come when I must confess, without any disguise, that the prevalence of those two odious practices of chewing and expectorating began about this time to be anything but agreeable, and soon became most offensive and sickening. In all the public places of America, this filthy custom is recognized. In the courts of law, the judge has his spittoon, the crier his, the witness his, and the prisoner his; while the jurymen and spectators are provided for, as so many men who in the course of nature must desire to spit incessantly. In the hospitals, the students of medicine are requested, by notices upon the wall, to eject their tobacco juice into the boxes provided for that purpose, and not to discolour the stairs. In public buildings, visitors are implored, through the same agency, to squirt the essence of their quids, or "plugs," as I have heard them called by gentlemen learned in this kind of sweetmeat, into the national spittoons, and not about the bases of the marble columns. But in some parts, this custom is inseparably mixed up with every meal and morning call, and with all the transactions of social life. The stranger, who follows in the track I took myself, will find it in its full bloom and glory, luxuriant in all its alarming recklessness, at Washington. And let him not persuade himself (as I once did, to my shame) that previous tourists have exaggerated its extent. The thing itself is an exaggeration of nastiness, which cannot be outdone. [Chapter VIII: "Washington. — The Legislature. — The President's House," 329-30]

Commentary: The Ubiquitous Spittoon and The Cigarette-Smoking Mania of the 1860s

The majority of American men Dickens encountered on his initial Reading Tour were given to what the Englishman regarded as a disgusting habit — chewing tobacco and expectorating the resultant juices. Although chewing and smoking of tabacco seem almost to have been indications of patriotism for many Americans prior to the Civil War, Nast agreed with Dickens's aversion to chewing tobacco. The "National Spittoon" in his illustration for Chapter VIII supplants that other symbol of American politics, The White House, which was the subject of A. B. Frost's illustration for this chapter.

Nast, ever the humorist, has a serpent's head rising through the foul smoke emanating from the mouth of the National Spittoon, amounting to characteristic visual hyperbole for the popular New York cartoonist. In what constitutes a subtitle, Nast describes Washington, D. C., as "The Head-Quarters of Tobacco-Tinctured Saliva," as if it rather than The White House or The Capitol is a more fitting symbol for the legislative and executive functions of the American federal government. Since Dickens had reacted to the chewing and expectorating of tobacco as abhorrent social practices common in "the public places of America," Nast's hyperbole in this illustration of the gigantic receptacle for saliva complements Dickens's sentiments precisely. The cartoonist reinforces the connection between the repulsive consumption of tobacco and American politics in the next illustration, the ironically entitled Honorable Member. In contrast, A. B. Frost in the British Household Edition (1880) shows neither a spittoon, nor the chewing or even smoking of tobacco among the dozen visitors to The White House.

Despite the implications of A. B. Frost's frontispiece for American Notes for General Circulation in the British Household Edition, Americans consumed tobacco chiefly in cigars, in pipes, in snuff, and particularly in the form of chewable tobacco until after the American Civil War. In fact, even cigar-smoking was not in vogue when Dickens first visited the United States; only after the 1846 war with Mexico did America become a nation of cigar rather than pipe smokers. The convenience of cigarettes meant that the market grew rapidly, enabling producers outside the Carolinas and Virginia to turn a profit with lighter grades of tobacco suitable for minced tobacco. The bright variety of tobacco was discovered by Union and Confederate troops alike during the Civil War. Ready-made cigarettes using mixtures of bright and burley tobacco allowed American manufacturers to develop cheaper brands. U.S. cigarette production boomed between 1870 and 1880, at just the time when Harper and Brothers and Chapman and Hall were partnering on the Household Edition.

The Spanish and French mania for cigarette-smoking had come to American shores during the war between the North and the South — and just in time. As liberated slaves left the tobacco plantations of the former Confederacy, tobacco farmers would have fallen on hard times with a much reduced labour force, were it not for the popularity of cigarettes. Whereas the rolling of cigars and the chopping of tobacco leaves for pipes were both labour-intensive, Albert Pease of Dayton, Ohio, advanced cigarette production considerably with his steam-powered shredding machine for processing the lighter tobacco leaves into cigarette tobacco. As the machine came into general use in the 1870s, the price of cigarettes fell, so that American males began to consume cigarettes in ever-increasing numbers. Up until the 1880s, cigarettes were still made by hand and were high in price. Overseas, European demand for the minced tobacco necessary to make cigarettes led to a boom in the American tobacco industry in the las two decades of the nineteenth century as widespread use of Pease's machine made high volumes of the product possible.

The Equivalent British Household Edition Illustration (1880)

Above: A. B. Frost's less humorous and more sober scene representing American politics, In The White House (1880). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Related Materials

- Charles Dickens, the traveler — places he visited

- Charles Dickens, 1843 daguerrotype by Unbek in America; the earliest known photographic portrait of the author

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.] Click on the image to enlarge it.

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Chapter VIII: "Washington. — The Legislature. — The President's House." Pictures from Italy, Sketches by Boz and American Notes. Illustrated by Thomas Nast and Arthur B. Frost. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1877 (copyrighted in 1876). 329-36.

Dickens, Charles. Chapter VIII: "Washington. The Legislature. And The President's House." American Notes for General Circulation and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by J. Gordon Thomson and A. B. Frost. London: Chapman and Hall, 1880. 297-312.

Kent, Christopher. "Smoking and Tobacco." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia. Ed. Sally Mitchell. New York: Garland, 1988. 727.

"Tobacco Industry." Dictionary of American History. The Gale Group: 2003. Encyclopedia.com.

Created 23 May 2019

Last modified 17 June 2020