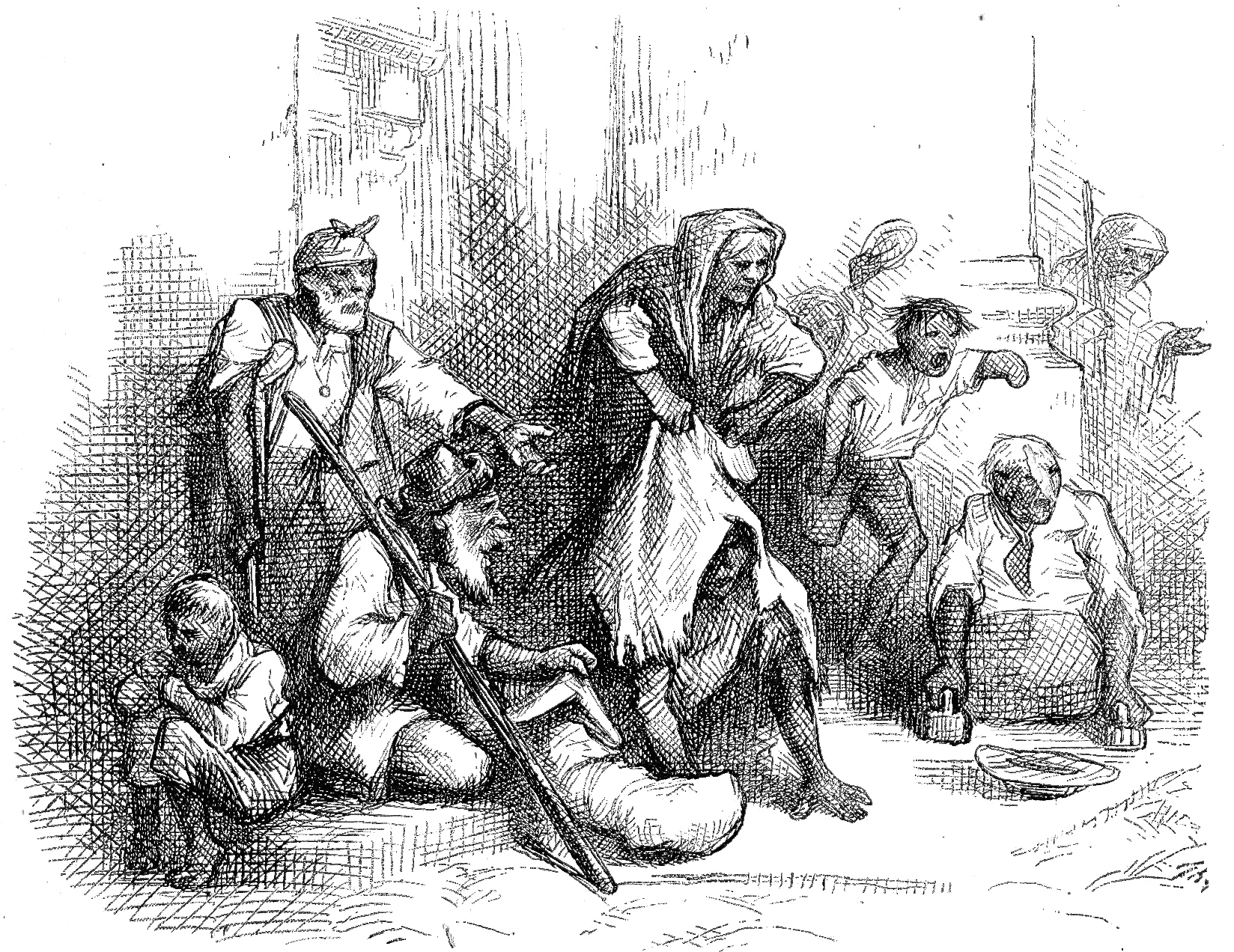

Beggars Everywhere by Thomas Nast, in Charles Dickens's Pictures from Italy, Sketches, and American Notes, tenth chapter, "To Rome by Pisa and Siena," page 50. Wood-engraving, 4 ⅛ by 5 ½ inches (10.2 cm high by 13.3 cm wide), vignetted. Descriptive headline: "Accommodations for Travellers."

Passage Illustrated: Not Picturesque, but Pathetically Backward

If Pisa be the seventh wonder of the world in right of its Tower, it may claim to be, at least, the second or third in right of its beggars. They waylay the unhappy visitor at every turn, escort him to every door he enters at, and lie in wait for him, with strong reinforcements, at every door by which they know he must come out. The grating of the portal on its hinges is the signal for a general shout, and the moment he appears, he is hemmed in, and fallen on, by heaps of rags and personal distortions. The beggars seem to embody all the trade and enterprise of Pisa. Nothing else is stirring, but warm air. Going through the streets, the fronts of the sleepy houses look like backs. They are all so still and quiet, and unlike houses with people in them, that the greater part of the city has the appearance of a city at daybreak, or during a general siesta of the population. Or it is yet more like those backgrounds of houses in common prints, or old engravings, where windows and doors are squarely indicated, and one figure (a beggar of course) is seen walking off by itself into illimitable perspective. [Chapter Ten, "To Rome by Pisa and Sienna," 50]

Commentary: Anti-Picturesque Beggars

Painters of the picturesque sometimes incorporated an impoverished, down-trodden peasantry, in their atmospheric landscapes partly for the sake of scale and partly for the sake of creating human interest — since the eighteenth century, the peasantry had constituted "a visual prop of picturesque scenery occurring in numberless sketches, prints and acquatints" (Orestano, 52). Dickens disapproved of this elitist exploitation of the poor as ornaments to contrast picturesque ruins with sentimental associations: "the term 'picturesque' is never uncritically attached by Dickens to any beggar or cripple or poor woman or ragged child he meets on his way" (Orestano, 53). Nast communicates Dickens's discomfort as an "unhappy visitor" or tourist at Pisa, for these beggars are neither benign, sentimental presences nor silently suffering indigents, but voracious and menacing petitioners.

Dickens's critique of the conventional picturesque associations expresses a cautious attitude towards the so-called aesthetics of poverty which marks his awareness — not unlike Ruskin's — of the aporia ethic/aesthetic already entangled with, and inextricable from, the picturesque agenda. [Orestano, 53]

Relevant Marcus Stone illustrations for Pictures from Italy

Related Material

- Samuel Palmer — Pictures from Italy

- Gordon Thomson — Playing at Mora

- Charles Dickens, the traveler — places he visited

- Genoa and its Neighbourhood

- Charles Dickens's Tours of Italy

- Dickens and Family at the Villa di Bella Vista (The Bagnerello), Albaro: July-September, 1844

- Charles Dickens, 1843 daguerrotype by Unbek in America; the earliest known photographic portrait of the author

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.] Click on the image to enlarge it.

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Chapter 10, "To Rome by Pisa and Sienna." Pictures from Italy, Sketches by Boz, and American Notes. Illustrated by A. B. Frost and Thomas Nast. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1877. 47-53.

_______. Pictures from Italy and American Notes. Illustrated by A. B. Frost and Gordon Thomson. London: Chapman and Hall, 1880. 1-381.

Orestano, Francesca. "Charles Dickens and Italy: The 'New Picturesque'.” Dickens and Italy: Little Dorrit and Pictures from Italy, ed. Michael Hollington and Francesca Orestano. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars, 2009. 49-67.

Created 15 May 2019

Last modified 8 June 2020