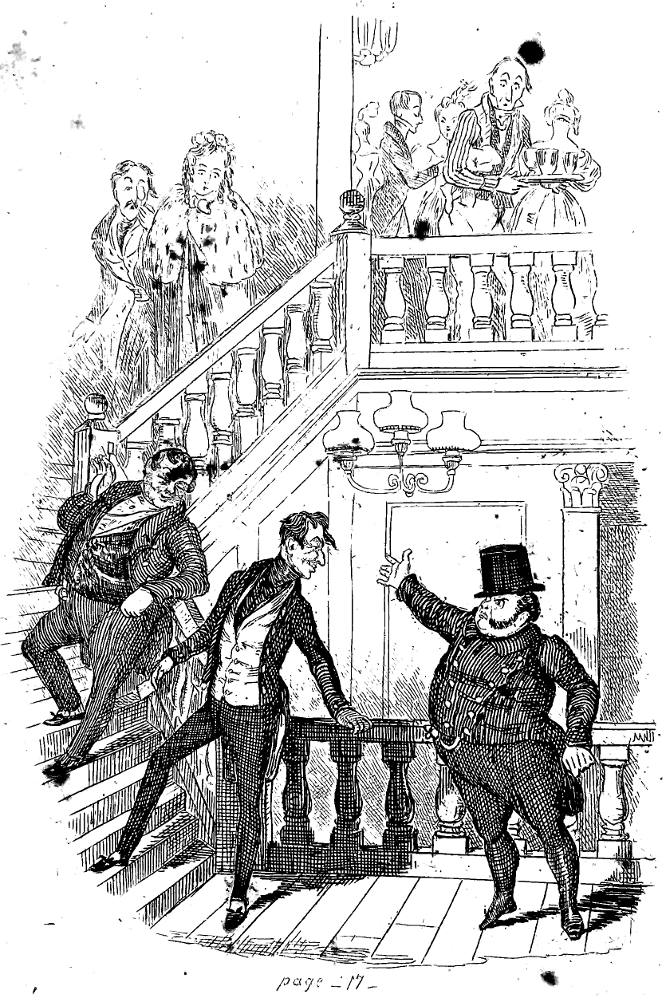

"Have you got everything?" said Mr. Winkle, in an agitated tone by Thomas Nast, in Charles Dickens's The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club, Chapter II, "The First Day's Journey, and the First Evening's Adventures; with their Consequences," page 20. Wood-engraving, 3 ½ inches high by 5 ½ inches wide (8.9 cm high by 13.4 cm wide), framed, half-page; referencing text on the present and facing page; descriptive headline: "On the Ground" (p. 21).

.Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: A Satire on Duelling

The state of the case having been formally explained to Mr. Snodgrass, and a case of satisfactory pistols, with the satisfactory accompaniments of powder, ball, and caps, having been hired from a manufacturer in Rochester, the two friends returned to their inn; Mr. Winkle to ruminate on the approaching struggle, and Mr. Snodgrass to arrange the weapons of war, and put them into proper order for immediate use.

It was a dull and heavy evening when they again sallied forth on their awkward errand. Mr. Winkle was muffled up in a huge cloak to escape observation, and Mr. Snodgrass bore under his the instruments of destruction.

"Have you got everything?" said Mr. Winkle, in an agitated tone.

"Everything," replied Mr. Snodgrass; "plenty of ammunition, in case the shots don’t take effect. There’s a quarter of a pound of powder in the case, and I have got two newspapers in my pocket for the loadings."

These were instances of friendship for which any man might reasonably feel most grateful. The presumption is, that the gratitude of Mr. Winkle was too powerful for utterance, as he said nothing, but continued to walk on — rather slowly.

"We are in excellent time," said Mr. Snodgrass, as they climbed the fence of the first field; "the sun is just going down." Mr. Winkle looked up at the declining orb and painfully thought of the probability of his ‘going down’ himself, before long.

"There’s the officer," exclaimed Mr. Winkle, after a few minutes walking. [Chapter II, "The First Day's Journey, and the First Evening's Adventures; with their Consequences," pp. 20-21]

Commentary: Different Approaches in the American and British Household Editions

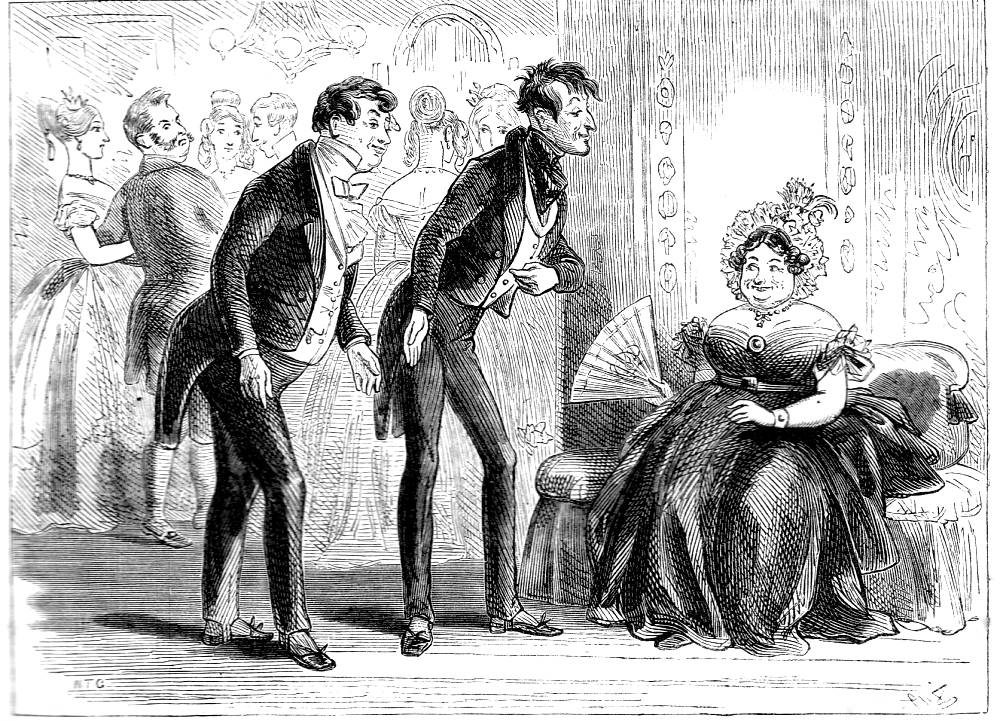

With the precedent of Seymour's illustration of the standard Victorian angry man, Dr. Slammer, before him, Nast shifted his subject entirely for his third regular illustration. Robert Seymour had focussed on the comic possibilities of mistaken identities arising from Dr. Slammer's challenging Alfred Jingle (dressed in Winkle's distinctive blue club suit) to a duel, in Dr. Slammer's Defiance (April 1836). Phiz's Household Edition illustration of Tupman and the "Stranger" (i. e., Alfred Jingle) being introduced to Mrs. Budger at the charity ball serves to introduce the slippery Jingle and the antipathy of Dr. Slammer, surgeon to the Ninety-seventh regiment, the angry man ("with a ring of upright black hair") looking indignantly at the outsiders and at the rich widow upon whom he has had designs for some time. (Although Dickens wrote the satirical chapter in the mid-1830s, he has set it in the 1820s, when military men in particular would call out those who who had besmirched their honour.)

Nast dispenses with these preliminaries entirely, and takes readers immediately to the hapless Winkle's having to prepare himself for duel — the causes of which he cannot remember because, of course, it was Jingle, wearing Winkle's coat, who had insulted the splenetic physician. Unfortunately, Nast's innovative handling produces a mediocre illustration with unrecognizable figures, little overt conflict, and a generalised country backdrop.

As various European countries in the nineteenth century sought to outlaw duelling with the conventional rapiers or the advanced weaponry of pistols, British authors began to ridicule the practice of defending one's honour in a pre-arranged duel as something of a joke — and certainly an archaic means of settling personal disputes. In Davenport Dunn (1857-58), illustrator Phiz and novelist Charles Lever demonstrate how European authorities by the 1850s had come to regard causing another's death in a duel as a form of homicide. Although the dueling culture of Great Britain had largely perished after the Napoleonic Wars, it survived in France, Italy, and Latin America well into the twentieth century. The practice had come to an end in Great Britain in 1852, when the last recorded duel was fought there. Moreover, in nineteenth-century France even participating in a duel could be a capital offense.

Relevant illustrations for Pickwick Papers (1836 & 1874)

Left: The original Robert Seymour steel-engraving which accompanied the initial monthly number: Dr. Slammer's Defiance/span> (April 1836). Right: Phiz's Household Edition illustration for the same chapter, What! Introducing his friend? (1874). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Duelling Scenes from Other Victorian Novels

- Phiz's The Country Manager Rehearses a Combat in Nicholas Nickleby (October 1838)

- Cruikshank's The Duel in Tothill Fields in The Miser's Daughter (July 1842)

- Cruikshank's After meditating desperate deeds of Duelling, Prussic Acid, Pistols, and Plunges in the River in The Progress of Mr. Lambkin (1844)

- Phiz's The Duel on Crabtree Green in Ainsworth's Mervyn Clitheroe (Part 5, 1857 Dec.)

- Phiz's The Duel in Davenport Dunn (February 1858)

- Fred Walker's Last Moments of the Count of Saverne in The Cornhill (April 1864)

Related Material

- Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens (homepage)

- Nast’s Pickwick illustrations

- The complete list of illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the original edition

- The complete list of illustrations by Phiz for the Household Edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. The Household Edition. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. New York: Harper and Brothers 1873.

Dickens, Charles. Pickwick Papers. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

Last modified 13 July 2019