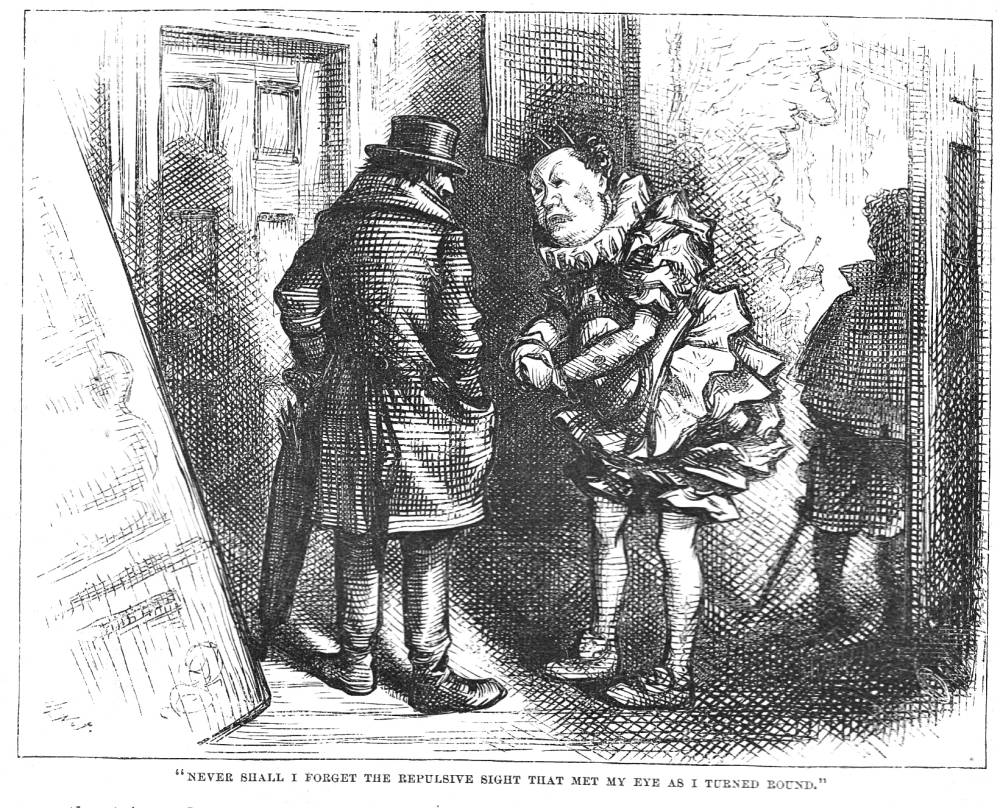

"Never shall I forget the repulsive sight that met my eyes I turned round" by Thomas Nast (1873) for Dickens's "The Stroller's Tale," the first of the interpolated short stories in Dickens's The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club (May 1836).

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliographical Note

The illustration appears in the American Household Edition of Charles Dickens's The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club, Chapter III, "The Stroller's Tale," page 24. Wood-engraving, 4 inches high by 5 ½ inches wide (10.2 cm high by 13.4 cm wide), framed, half-page; referencing text on the previous page; descriptive headline: "The Sick Clown" (p. 25). New York: Harper & Bros., Franklin Square, 1873. The interpolated short story, originally published in the second serial instalment in May 1836, was accompanied by Seymour's piece of social realism, The Dying Clown, a standard death-bed scene. In the other Household Edition volume, published in London the following year by Chapman and Hall, Phiz seems to have avoided the melancholy subject of the professional entertainer's drinking himself to death.

Passage Illustrated: Dismal Jemmy's Inset Narrative

"About this time, and when he had been existing for upwards of a year no one knew how, I had a short engagement at one of the theatres on the Surrey side of the water, and here I saw this man, whom I had lost sight of for some time; for I had been travelling in the provinces, and he had been skulking in the lanes and alleys of London. I was dressed to leave the house, and was crossing the stage on my way out, when he tapped me on the shoulder. Never shall I forget the repulsive sight that met my eye when I turned round. He was dressed for the pantomimes in all the absurdity of a clown's costume. The spectral figures in the Dance of Death, the most frightful shapes that the ablest painter ever portrayed on canvas, never presented an appearance half so ghastly. His bloated body and shrunken legs — their deformity enhanced a hundredfold by the fantastic dress — the glassy eyes, contrasting fearfully with the thick white paint with which the face was besmeared; the grotesquely-ornamented head, trembling with paralysis, and the long skinny hands, rubbed with white chalk—all gave him a hideous and unnatural appearance, of which no description could convey an adequate idea, and which, to this day, I shudder to think of. His voice was hollow and tremulous as he took me aside, and in broken words recounted a long catalogue of sickness and privations, terminating as usual with an urgent request for the loan of a trifling sum of money. I put a few shillings in his hand, and as I turned away I heard the roar of laughter which followed his first tumble on the stage. [Chapter III, "The Stroller's Tale," p. 23]

Commentary: An Interpolated, Cautionary Tale

Even though "The Stroller's Tale" (May 1836) is only Dickens's fourth published short story, it demonstrates a starling maturity in its author's handling of the form of the inset narrative. The distinctive narrative voice in the framed oral tale is not that of the of the "editor" of The Pickwick Papers but a strolling player whom the Pickwickians encounter in the Medway town, an actor nicknamed "Dismal Jemmy." Supposedly based on his relationship with an alcoholic pantomime clown, the story provides a tonal shift from the jolly camaraderie of the members of the Pickwick Club as they begin their sporting and cultural expedition beyond the English metropolis. Working in the picaresque tradition, Dickens seems to have relied extensively on the interpolated tale to vary voices, settings, and issues with which he could deal; the novel contains no less than nine such tales, one of which, "The Drunkard's Death" shares the present tale's tee-total message. In Dickens and the Short Story, Deborah A. Thomas succinctly describes "The Stroller's Tale" as "a grim description of the ravings of an alcoholic clown, who dies in the midst of financial, physical, and marital ruin" (20).

Despite his having the precedent of Robert Seymour's 1836 serial illustration The Dying Clown, Thomas Nast elected to try a novel approach which would underscore the theatrical context of Dismal Jemmy's cautionary tale. Nast shows the narrator ("Dismal Jemmy," otherwise James Hutley) with his back to the viewer, and focuses upon the clown in whiteface, about to resume his role in the pantomime. A second clown also stands ready to make his entrance. One cannot read the signs of paranoia on his mask-like face, but one can see that his legs are emaciated. He will shortly be used up, like the failing piece of stage scenery to the left. The cautionary tale warns readers of the dangers of alcohol abuse, which leads directly, according to Dismal Jemmy, to spousal-abuse, poverty, full-blown dementia, and premature death.

Whereas Seymour's steel-engraving constitutes standard, cautionary fare in which a flawed if not evil protagonist dies a painful death surrounded by his sorrowful family, Nast emphasizes the theatrical vocation of the dying alcoholic whose role (ironically) involves making audiences filled with children laugh at his uproarious gymnastics and pratfalls. Whereas the original illustration references the dying man's vocation only indirectly, through bits of clown costume and theatrical properties, Nast's approach involves demonstrating the Clown's continuing to practise his art, despite signs of an obvious physical and psychological decline. Immediately after he goes on stage, the clown delights the audience: "as I turned away I heard the roar of laughter which followed his first tumble on the stage" suggests that he has retained his ability to play to an audience in the popular persona of the white-faced "Joey," emulating the quintessential pantomime performer Joey Grimaldi. Nast here may also have had in mind Grimaldi's autobiography (edited by Dickens) which George Cruikshank illustrated with such scenes as Live Properties in the 1838 edition to demonstrate Grimaldi's stage persona. Dickens's story takes readers behind the jovial persona, and explores the personal tragedy behind the traditional visage which Nast captures so effectively. The illustrator shows a piece of stage scenery askew to provide the theatrical context, which the reader sees, as it were, from behind Dismal Jemmy.

That Dickens's pathetically addicted protagonist is a pantomime clown is all the more ironic if we consider the centrality of the form of the pantomime in the writer's memories of Christmas as a child:

One of the most popular Christmas treats for the Dickens family was a visit to the pantomime, and the young Dickens was thrilled when he was able to see his hero, the great Clown, Joseph Grimaldi, perform on stage, in 1819 and 1820. Almost twenty years later, Dickens was given the job of editing Grimaldi’s memoirs, ensuring that the memories of those pantomimes remained vivid in his mind. {Hwksley, p. 39]

Plates by other illustrators for "The Stroller's Tale," 1836 and 1910

Left: The May 1836 serial instalment of the novel provided a standard Victorian death-bed scene, Seymour's The Dying Clown. Centre: Harry Furniss's Charles Dickens Library Edition characterisation of the teller of the tale that reduces the dying pantomime clown tio a pair of claw-like hands, The Stroller's Tale (1910). Right: Clayton J. Clarke's Player's Cigarette card shows the moody tale-teller entirely wrapped up in a closed posture: Dismal Jemmy (1910). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Related Material

- Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens (homepage)

- Nast’s Pickwick illustrations

- The complete list of illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the original edition

- The complete list of illustrations by Phiz for the Household Edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

Related Materials: Dickens's Short Fiction, 1833-68

- Interpolated Tales in Dickens's Pickwick Papers

- A Comprehensive List of Dickens's Short Fiction, 1833-1868

- An Overview of Dickens's Short Fiction, 1833-1868

- A Critical Analysis of Dickens's Short Fiction, 1833-68

- Dickens' Aesthetic of the Short Story

- The Victorian Short Story: A Brief History

Related Materials: Victorian Pantomime

- Victorian Pantomimes and Extravaganzas

- The Development of Pantomime, 1692-1761

- Pantomime, 1844

- Nineteenth-Century British Pantomime

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Dickens, Charles. "Pickwick Papers. Illustrated by Robert Seymour and Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman & Hall, 1836-37.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. The Household Edition. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. New York: Harper and Brothers 1873.

Dickens, Charles. Pickwick Papers. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

Dickens Hawksley, Lucinda. "The Dickens Family and Christmas." The Dickens Magazine, Series 7, Issue 1 (2019): 39-40.

Patten, Robert L. "The Art of Pickwick's Interpolated Tales." ELH 34 (1967): 349-66.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and the Short Story. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Last modified 9 August 2019