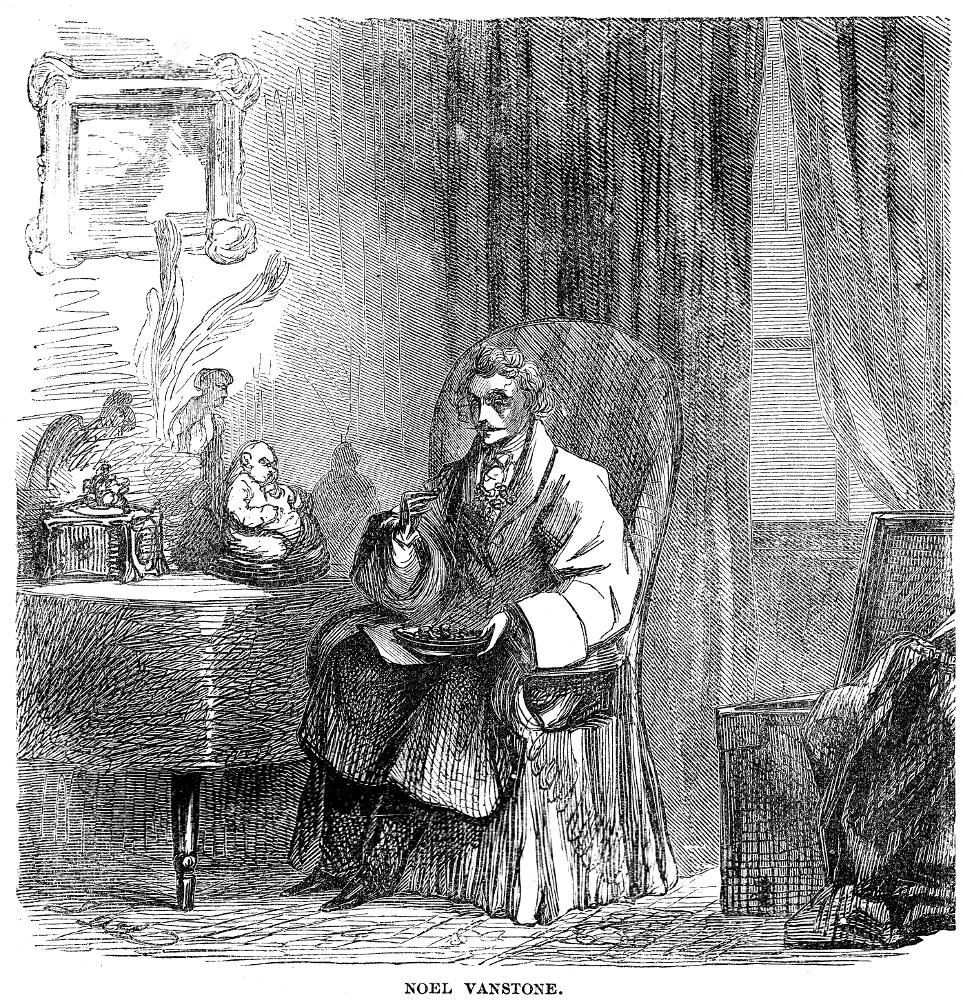

Noel Vanstone. Wood-engraving 11.6 cm high by 11.5 cm wide, or 4 ½ inches square, framed, for instalment eighteen in the American serialisation of Wilkie Collins’s No Name in Harper’s Weekly [Vol. VI. — No. 289] Number 18, “The Third Scene — Vauxhall Walk, Lambeth.” Chapter III (page 445; p. 114 in volume), plus an uncaptioned vignette of Magdalen, in disguise (veiled), and Mrs. Lecount (p. 118 in volume): 10.1 cm high by 5.6 cm wide, or 3 ⅞ inches high by 2 ¼ inches wide, vignetted. [Instalment No. 18 ends in the American serialisation on page 446, at the end of Chapter III. Precisely the same number without illustration ran on 12 July 1862 in All the Year Round.]

Passage Illustrated in the Main Plate: Noel Vanstone interviews Magdalen Disguised

Magdalen found herself in a long, narrow room, consisting of a back parlor and a front parlor, which had been thrown into one by opening the folding-doors between them. Seated not far from the front window, with his back to the light, she saw a frail, flaxen-haired, self-satisfied little man, clothed in a fair white dressing-gown many sizes too large for him, with a nosegay of violets drawn neatly through the button-hole over his breast. He looked from thirty to five-and-thirty years old. His complexion was as delicate as a young girl’s, his eyes were of the lightest blue, his upper lip was adorned by a weak little white mustache, waxed and twisted at either end into a thin spiral curl. When any object specially attracted his attention he half closed his eyelids to look at it. When he smiled, the skin at his temples crumpled itself up into a nest of wicked little wrinkles. He had a plate of strawberries on his lap, with a napkin under them to preserve the purity of his white dressing-gown. At his right hand stood a large round table, covered with a collection of foreign curiosities, which seemed to have been brought together from the four quarters of the globe. Stuffed birds from Africa, porcelain monsters from China, silver ornaments and utensils from India and Peru, mosaic work from Italy, and bronzes from France, were all heaped together pell-mell with the coarse deal boxes and dingy leather cases which served to pack them for traveling. The little man apologized, with a cheerful and simpering conceit, for his litter of curiosities, his dressing-gown, and his delicate health; and, waving his hand toward a chair, placed his attention, with pragmatical politeness, at the visitor’s disposal. Magdalen looked at him with a momentary doubt whether Mrs. Lecount had not deceived her. Was this the man who mercilessly followed the path on which his merciless father had walked before him? She could hardly believe it. “Take a seat, Miss Garth,” he repeated, observing her hesitation, and announcing his own name in a high, thin, fretfully-consequential voice: “I am Mr. Noel Vanstone. You wished to see me — here I am!” [Chapter III: page 445 in serial; pp. 113-114 in volume]

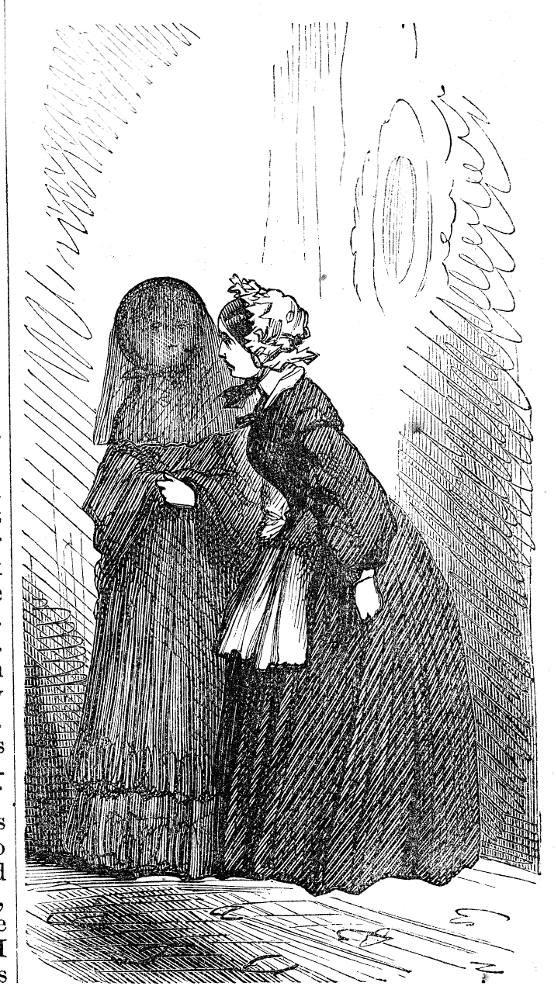

Passage Illustrated in the Vignette: Magdalen Disguised and Mrs. Lecount

She followed Magdalen into the passage, and closed the door of the room after her.

“Are you residing in London, ma’am?” asked Mrs. Lecount.

“No,” replied Magdalen. “I reside in the country.”

“If I want to write to you, where can I address my letter?”

“To the post-office, Birmingham,” said Magdalen, mentioning the place which she had last left, and at which all letters were still addressed to her.

Mrs. Lecount repeated the direction to fix it in her memory, advanced two steps in the passage, and quietly laid her right hand on Magdalen’s arm.

“A word of advice, ma’am,” she said; “one word at parting. You are a bold woman and a clever woman. Don’t be too bold; don’t be too clever. You are risking more than you think for.” She suddenly raised herself on tiptoe and whispered the next words in Magdalen’s ear. “I hold you in the hollow of my hand!” said Mrs. Lecount, with a fierce hissing emphasis on every syllable. Her left hand clinched itself stealthily as she spoke. It was the hand in which she had concealed the fragment of stuff from Magdalen’s gown — the hand which held it fast at that moment.

“What do you mean?” asked Magdalen, pushing her back.

Mrs. Lecount glided away politely to open the house door. [Chapter III: page 446 in serial; pp. 118-119 in volume]

Commentary: Interesting Props and an Inoffensive Image of the Housekeeper

The pair of illustrations serve as bookends for Magdalen’s interview with her greedy cousin. The dominant feature in the portrait of the elegantly attired Noel Vanstone in his dimly lit parlour is the exotic foreign bric-à-brac on his side-table: “Stuffed birds from Africa, porcelain monsters from China, silver ornaments and utensils from India and Peru” (p. 113, in advance of the textual illustration). McLenan renders the devious heir enigmatic by giving him a mask-like face, thrown into the shadows; he is doubly peculiar by virtue of his slender, effeminate hands. For all his cowardliness, Noel Vanstone over the course of the extended interview proves a worthy adversary as his disguised cousin characterizes her charges as victimized orphans. Refusing her request, Vanstone petulantly enunciates the adage “A fool and his money are soon parted” (116). He remains adamant about giving each of the sisters only a hunded pounds out of their father’s estate.

Ironically, although the pasteboard cousin is the focus of the main illustration, his highly capable and suspicious aid, Mrs. Lecount, is the focal character in the accompanying text. The vignette does not do justice to Collins's description of the crafty housekeeper, although McLenan has attempted to incorporate as much of the verbal portrait as possible:

Magdalen turned, and confronted Mrs. Lecount. She had expected — founding her anticipations on the letter which the housekeeper had written to her — to see a hard, wily, ill-favored, insolent old woman. She found herself in the presence of a lady of mild, ingratiating manners, whose dress was the perfection of neatness, taste, and matronly simplicity, whose personal appearance was little less than a triumph of physical resistance to the deteriorating influence of time. If Mrs. Lecount had struck some fifteen or sixteen years off her real age, and had asserted herself to be eight-and-thirty, there would not have been one man in a thousand, or one woman in a hundred, who would have hesitated to believe her. Her dark hair was just turning to gray, and no more. It was plainly parted under a spotless lace cap, sparingly ornamented with mourning ribbons. Not a wrinkle appeared on her smooth white forehead, or her plump white cheeks. Her double chin was dimpled, and her teeth were marvels of whiteness and regularity. Her lips might have been critically considered as too thin, if they had not been accustomed to make the best of their defects by means of a pleading and persuasive smile. Her large black eyes might have looked fierce if they had been set in the face of another woman, they were mild and melting in the face of Mrs. Lecount; they were tenderly interested in everything she looked at — in Magdalen, in the toad on the rock-work, in the back-yard view from the window; in her own plump fair hands, — which she rubbed softly one over the other while she spoke; in her own pretty cambric chemisette, which she had a habit of looking at complacently while she listened to others. The elegant black gown in which she mourned the memory of Michael Vanstone was not a mere dress — it was a well-made compliment paid to Death. Her innocent white muslin apron was a little domestic poem in itself. Her jet earrings were so modest in their pretensions that a Quaker might have looked at them and committed no sin. The comely plumpness of her face was matched by the comely plumpness of her figure; it glided smoothly over the ground; it flowed in sedate undulations when she walked. [Chapter II: page 422 in serial; p. 111 in volume]

Commentary: The Trying Experience of the Enigmatic Master and His Devious Housekeeper

In the vignette, Mrs. Lecount, demurely dressed as a maid, peers into the veil obscuring her visitor’s face, as if she is trying to penetrate Magdalen’s disguise. Maintaining her somewhat theatrical façade is crucial to Magdalen’s obtaining an interview with him, and assessing him as a worthy antagonist as she strategizes as how to recoup her lost inheritance. Is her true adversary not her effeminate cousin, but his shrewd but “comely” middle-aged housekeeper with the “mild and melting . . . face”? Why does her cousin count her “a domestic treasure” (114) rather than a mere underling? And does this fulsome praise really originate with Noel, or has he been instructed beforehand as to what to say? The devious pair certainly tax Magdalen’s (Miss Garth’s) self-control during the interview; McLennan has omitted the true visual curiosity of the house, Noel Vanstone’s Aquarium, a rarity in England at the time.

Related Material

- Frontispiece to Wilkie Collins’s No Name (1864) by John Everett Millais

- Victorian Paratextuality: Pictorial Frontispieces and Pictorial Title-Pages

- Wilkie Collins's No Name (1862): Charles Dickens, Sheridan's The Rivals, and the Lost Franklin Expedition

- "The Law of Abduction": Marriage and Divorce in Victorian Sensation and Mission Novels

- Gordon Thomson's A Poser from Fun (5 April 1862)

- Kate Egan's Playthings to Men: Women, Power, and Money in Gaskell and Trollope

- Philip V. Allingham, The Victorian Sensation Novel, 1860-1880 — "preaching to the nerves instead of the judgment"

Image scans and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Blain, Virginia. “Introduction” and “Explanatory Notes” to Wilkie Collins's No Name. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.