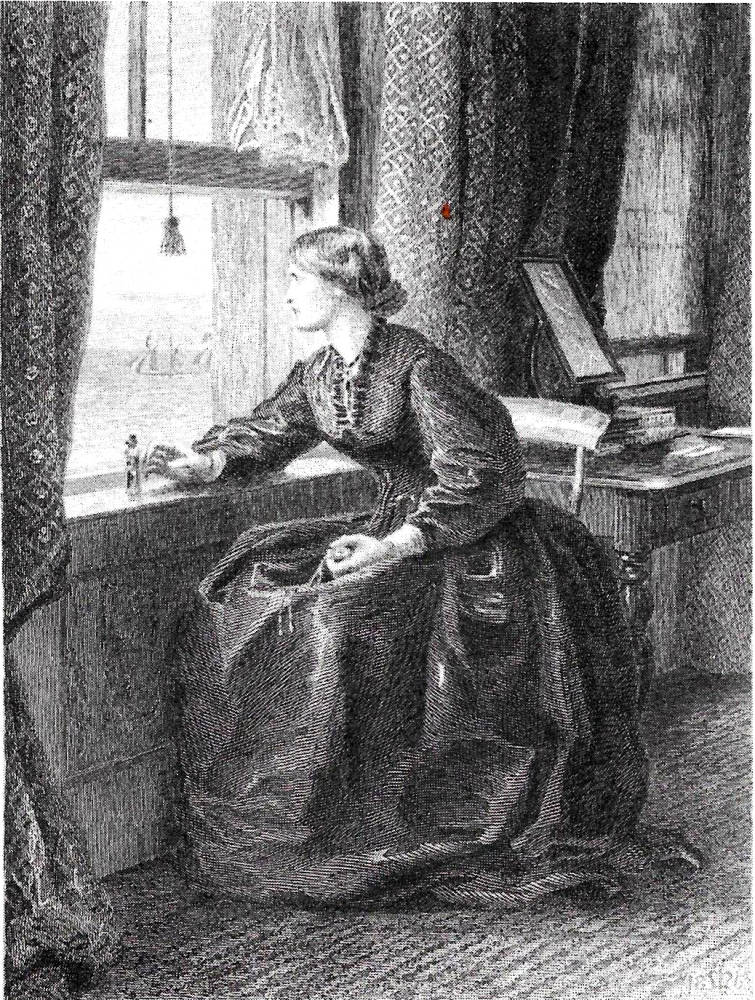

Frontispiece

Artist: John Everett Millais

Engraver: John Saddler

1864

Steel-engraving

4 ¼ x 3 ¼ inches

Wilkie Collins’s No Name

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image, caption material and commentary by Simon Cooke; passage illustrated and final comment added by Phiip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Realised: Magdalen Contemplates Committing Suicide

The new day had risen. The broad gray dawn flowed in on her, over the quiet eastern sea.

She saw the waters heaving, large and silent, in the misty calm; she felt the fresh breath of the morning flutter cool on her face. Her strength returned; her mind cleared a little. At the sight of the sea, her memory recalled the walk in the garden overnight, and the picture which her distempered fancy had painted on the black void. In thought, she saw the picture again — the murderer hurling the Spud of the plow into the air, and setting the life or death of the woman who had deserted him on the hazard of the falling point. The infection of that terrible superstition seized on her mind as suddenly as the new day had burst on her view. The promise of release which she saw in it from the horror of her own hesitation roused the last energies of her despair. She resolved to end the struggle by setting her life or death on the hazard of a chance.

On what chance?

The sea showed it to her. Dimly distinguishable through the mist, she saw a little fleet of coasting-vessels slowly drifting toward the house, all following the same direction with the favoring set of the tide. In half an hour — perhaps in less — the fleet would have passed her window. The hands of her watch pointed to four o’clock. She seated herself close at the side of the window, with her back toward the quarter from which the vessels were drifting down on her — with the poison placed on the window-sill and the watch on her lap. For one half-hour to come she determined to wait there and count the vessels as they went by. If in that time an even number passed her, the sign given should be a sign to live. If the uneven number prevailed, the end should be Death.

With that final resolution, she rested her head against the window and waited for the ships to pass.

The first came, high, dark and near in the mist, gliding silently over the silent sea. An interval — and the second followed, with the third close after it. Another interval, longer and longer drawn out — and nothing passed. She looked at her watch. Twelve minutes, and three ships. Three.

The fourth came, slower than the rest, larger than the rest, further off in the mist than the rest. The interval followed; a long interval once more. Then the next vessel passed, darkest and nearest of all. Five. The next uneven number —

Five.

She looked at her watch again. Nineteen minutes, and five ships. Twenty minutes. Twenty-one, two, three — and no sixth vessel. Twenty-four, and the sixth came by. Twenty-five, twenty-six, twenty-seven, twenty-eight, and the next uneven number — the fatal Seven—glided into view. Two minutes to the end of the half-hour. And seven ships.

Twenty-nine, and nothing followed in the wake of the seventh ship. The minute-hand of the watch moved on half-way to thirty, and still the white heaving sea was a misty blank. Without moving her head from the window, she took the poison in one hand, and raised the watch in the other. As the quick seconds counted each other out, her eyes, as quick as they, looked from the watch to the sea, from the sea to the watch—looked for the last time at the sea — and saw the EIGHTH ship.

She never moved, she never spoke. The death of thought, the death of feeling, seemed to have come to her already. She put back the poison mechanically on the ledge of the window and watched, as in a dream, the ship gliding smoothly on its silent way — gliding till it melted dimly into shadow — gliding till it was lost in the mist.

The strain on her mind relaxed when the Messenger of Life had passed from her sight.

“Providence?” she whispered faintly to herself. “Or chance?” [Chapter XIII, “The Fourth Scene. Aldborough, Suffolk.” pp. 417-418 in the Dover edition; p. 647 in Harper's Weekly, 11 October 1862]

Commentary: The Frontispiece as a Significant Paratextual Element

In sensational narratives the frontispiece almost always prepares the reader for the tale’s febrile tone by showing a dynamic moment of emotional crisis, revelation, a shocking encounter or some other melodramatic moment. John Everett Millais’s frontispiece for the illustrated edition of Wilkie Collins’s No Name (1864) exemplifies this approach. Digging deep into the novel, Millais shows the moment when Magdalen Vanstone considers suicide, about to clutch the vial of poison as she looks out of the window at the sea; if a certain ship goes by she will take it, if not, she will live. Millais depicts the figure in a tense pose, intently looking outward, the embodiment of anxious stress. In so doing he projects the character’s situation and suggests her psychological resilience. Acting as a crystallized epitome of the book’s theme – should she face up to the shame of illegitimacy or despair and kill herself? – It is a powerful means of immersing the reader in situations that are yet to unfold. — Simon Cooke, “Victorian Paratextuality: Pictorial Frontispieces and Pictorial Title-Pages”

Magdalen Vanstone Contemplates Suicide in Millais' Steel-engraving (1864)

As the complementary passage suggests, Magdalen has come to such an emotional pass that she decides to let Fate or Providence determine whether she lives or dies this night. Millais captures the image of Collins's protagonist at a moment of crisis: she looks out on the peaceful English Channel as she contemplates suicide as a logical way out of her predicament. At the head of the scene, Collins has admirably established the mood and the setting: “It was past two o’clock when she shut herself up alone in her room. Her chair stood in its customary place by the toilet-table” (415). Magdalen now finds herself in a fatalistic mood, torn between feelings of shame at her illegitimacy and her past misdemeanours and her desire for happiness. The sombre steel-engraving complements the sitter's pensive mood as the illustrator captures his subject's anxiety and internal conflict. The liminal positions of the sitter — between ocean and land, and night and day — suggest the girl's ambiguous social position, as well as her desire for both stability in her life and the chance to revolt against an unjust social order.

Related Material

- Victorian Paratextuality: Pictorial Frontispieces and Pictorial Title-Pages

- "I can twist any man alive around my finger!"

- Wilkie Collins's No Name (1862): Charles Dickens, Sheridan's The Rivals, and the Lost Franklin Expedition

Bibliography

Collins, Wilkie. No Name [cheap edition]. London: Sampson & Low, 1864.

Collins, William Wilkie. No Name . Illustrated by John Mclenan. New York: Dover Publications, 1978.

Collins, William Wilkie. No Name . Illustrated by John Mclenan. New York: Harper & Bros., 1864.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illus-

tration

J. E.

Millais

Next

Created 19 October 2012

last modified 5 September 2025