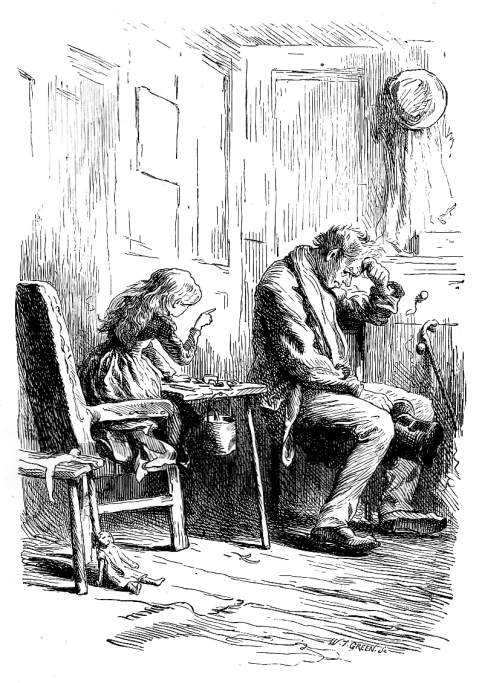

"There, there, there!" said Miss Wren. "For goodness' sake, stop, giant, or I shall be swallowed up alive before I know it." (p. 416, Chapman and Hall) — James Mahoney's fifty-eighth illustration for Charles Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, Household Edition (London), 1875. Wood engraving by the Dalziels, 9.3 cm high x 13.3 cm wide. The Harper and Brothers caption for the same woodcut for the fourth book's sixteenth chapter, "Persons and Things in General," is different: "Don't open your mouth as wide as that, young man, or it'll catch so, and not shut again some day." (p. 342). This final composite wood-engraving concerns the comic meeting between the "giant," the orphan Sloppy, adopted by Betty Higden from the local workhouse and employed by the Boffins, and the diminutive cripple, the sharp-tongued, perceptive Jenny Wren, the dolls' dressmaker.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passages Illustrated in Book Four, Chapter 16

The dolls' dressmaker, being at work for the Inexhaustible upon a full-dressed doll some two sizes larger than that young person, Mr Sloppy undertook to call for it, and did so. "Come in, sir," said Miss Wren, who was working at her bench. "And who may you be?"

Mr. Sloppy introduced himself by name and buttons.

"Oh indeed!" cried Jenny. "Ah! I have been looking forward to knowing you. I heard of your distinguishing yourself."

"Did you, Miss?" grinned Sloppy. "I am sure I am glad to hear it, but I don't know how."

"Pitching somebody into a mud-cart," said Miss Wren.

"Oh! That way!" cried Sloppy. "Yes, Miss." And threw back his head and laughed.

"Bless us!" exclaimed Miss Wren, with a start. "Don't open your mouth as wide as that, young man, or it'll catch so, and not shut again some day."

Mr. Sloppy opened it, if possible, wider, and kept it open until his laugh was out.

"Why, you're like the giant," said Miss Wren, "when he came home in the land of Beanstalk, and wanted Jack for supper."

"Was he good-looking, Miss?" asked Sloppy.

"No," said Miss Wren. "Ugly." — Book Four, Chapter 16, "Persons and Things in General," p. 256-257 (Chapman & Hall); p. 341-342 (Harper & Bros.)

"Where is he coming from, Miss?"

"Why, good gracious, how can I tell! He is coming from somewhere or other, I suppose, and he is coming some day or other, I suppose. I don't know any more about him, at present."

This tickled Mr. Sloppy as an extraordinarily good joke, and he threw back his head and laughed with measureless enjoyment. At the sight of him laughing in that absurd way, the dolls' dressmaker laughed very heartily indeed. So they both laughed, till they were tired.

"There, there, there!" said Miss Wren. "For goodness' sake, stop, Giant, or I shall be swallowed up alive, before I know it. And to this minute you haven't said what you've come for."

"I have come for little Miss Harmonses doll," said Sloppy. — Book Four, Chapter 16, "Persons and Things in General," p. 256-257 (Chapman & Hall); p. 343 (Harper & Bros.)

Commentary

Since it was his visual antecedent, Mahoney's 1875 treatment of the textual material is often his response to the original series of forty illustrations by young Marcus Stone, Dickens's 1860s serial and volume illustrator after Dickens's dropping Hablot Knight Browne, his principal illustrator for twenty-fiveyears. Although Mahoney sometimes accepts Stone's notions, with a greater number of illustrations to complete, Mahoney was quite free to innovate, adding scenes that Stone had not attempted. Whereas the final Stone illustration, Not to be Shaken off (November 1865) anticipates the climactic confrontation of Bradley Headstone and his blackmailer that leads to their melodramatic mutual destruction, the Household Edition illustrator had the opportunity to end the novel on a comic note by bringing together the ever-optimistic "natural," Sloppy, a child in an adult body, and the pessimistic "knowing child," Jenny Wren.

Whereas Mahoney has already dealt fairly extensively with these decidedly odd outsiders, Stone has essentially neglected them, depicting "Jenny" (Fanny Cleaver) significantly in just two illustrations — The Person of the House and the Bad Child (October 1864) and Miss Wren fixes her Idea (October 1865) — and not depicting Sloppy even once. Mahoney, therefore, fills in the blanks by depicting these comic figures, especially Sloppy, to enhance the "streaky bacon" effect of the novel by accentuating both comedic, romantic, and melodramatic strands, seen from the first in Dickens's works in such scenes as Nancy in hysterics in Oliver Twist and in Pickwick's stay in debtors' prison in such scenes as Phiz's The Warden's Room. Mahoney's conception of Sloppy is consistent with that of Sol Eytinge, Junior, in Mrs. Higden, Sloppy, and the Innocents (1867). Although he is not likely to have seen this illustration by his transAtlantic colleague, he responded to the same descriptive passages and likewise realised the significance of Sloppy's comic contribution to the texture of the sprawling novel:

Of an ungainly make was Sloppy. Too much of him longwise, too little of him broadwise, and too many sharp angles of him angle-wise. One of those shambling male human creatures, born to be indiscreetly candid in the revelation of buttons; every button he had about him glaring at the public to a quite preternatural extent. A considerable capital of knee and elbow and wrist and ankle, had Sloppy, and he didn't know how to dispose of it to the best advantage, but was always investing it in wrong s ecurities, and so getting himself into embarrassed circumstances. Full-Private Number One in the Awkward Squad of the rank and file of life, was Sloppy, and yet had his glimmering notions of standing true to the Colours. — Book One, Ch. 16, "Minders and Reminders," p. 102 in the Chapman and Hall Edition.

Thus, Mahoney depicts "the long boy" (100) when he introduces Betty Higden in "Come here, Toddles and Poddles" in Chapter 16, when Mrs. Boffin and the Secretary pay her a call in quest of an orphan to adopt. In this final illustration, which ends the narrative on both a humorous and speculative note, Mahoney underscores Dickens's tantalizingly raising the prospect of a romance between good-natured but learning disabled cabinet-maker Sloppy and the dolls' dressmaker Jenny Wren. Mahoney, then, would likely have disagreed with those critics who take issue with this possible closure, believing that Dickens only paired the two together because of their complementary physical and mental disabilities — and personalities. Interestingly, Dickens describes both of them as readers, and therefore as models for construing prose, even though Jenny was quite wrong for some time in her reading of Fledgeby and Riah. In a chapter whose function is "to set all matters right" (411), it does not seem likely that this meeting of Jenny and Sloppy is a red herring; rather, in a relationship with Sloppy Jenny will get to be a doting rather than a reprimanding parent while Sloppy will continue to be of service, for this is a narrative, in the final analysis, governed by the principles of poetic justice — and this is but "the first interview between Mr. Sloppy and Miss Wren" (413), and, as the picture implies, he is very taken with her hair, which she has just shaken loose: she "is not displeased by the effect it had made."

Sloppy and Jenny Wren in the various editions, 1864-1867

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's 1867 group character study of Betty Higden's atypical family, Mrs. Higden, Sloppy, and the Innocents. Right: Marcus Stone's depiction of Jenny Wren's chastising her alcoholic father, The Person of the House and the Bad Child (October 1864). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: Marcus Stone's interpretation of the scene in which Jenny finally understands Riah's true character, Miss Wren fixes her Idea (Part 18, October 1865). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

The Characters of Charles Dickens pourtrayed in a series of original watercolours by "Kyd." London, Paris, and New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, n. d.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "The Illustrators of Our Mutual Friend, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Marcus Stone, Charles Collins, Luke Fildes." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Canton: Ohio U. P., 1980. Pp. 203-228.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone [40 composite wood-block engravings]. Volume 14 of the Authentic Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901 [based on the original nineteen-month serial and the two-volume edition of 1865].

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1866. Vol. 1.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Illustrated Household Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Field; Lee and Shepard; New York: Charles T. Dillingham, 1870 [first published in The Diamond Edition, 1867].

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall' New York: Harper & Bros., 1875.

Grass, Sean. Charles Dickens's 'Our Mutual Friend': A Publishing History. Burlington, VT, and Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2014.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 21: The Other Novels." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp.441-442.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. (1899). Rpt. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2004.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

"Our Mutual Friend — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Queen's University, Belfast. "Charles Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, Clarendon Edition. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, June 1864-December 1865." Accessed 12 November 2105. http://www.qub.ac.uk/our-mutual-friend/witnesses/Harpers/Harpers.htm

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 19 January 2016