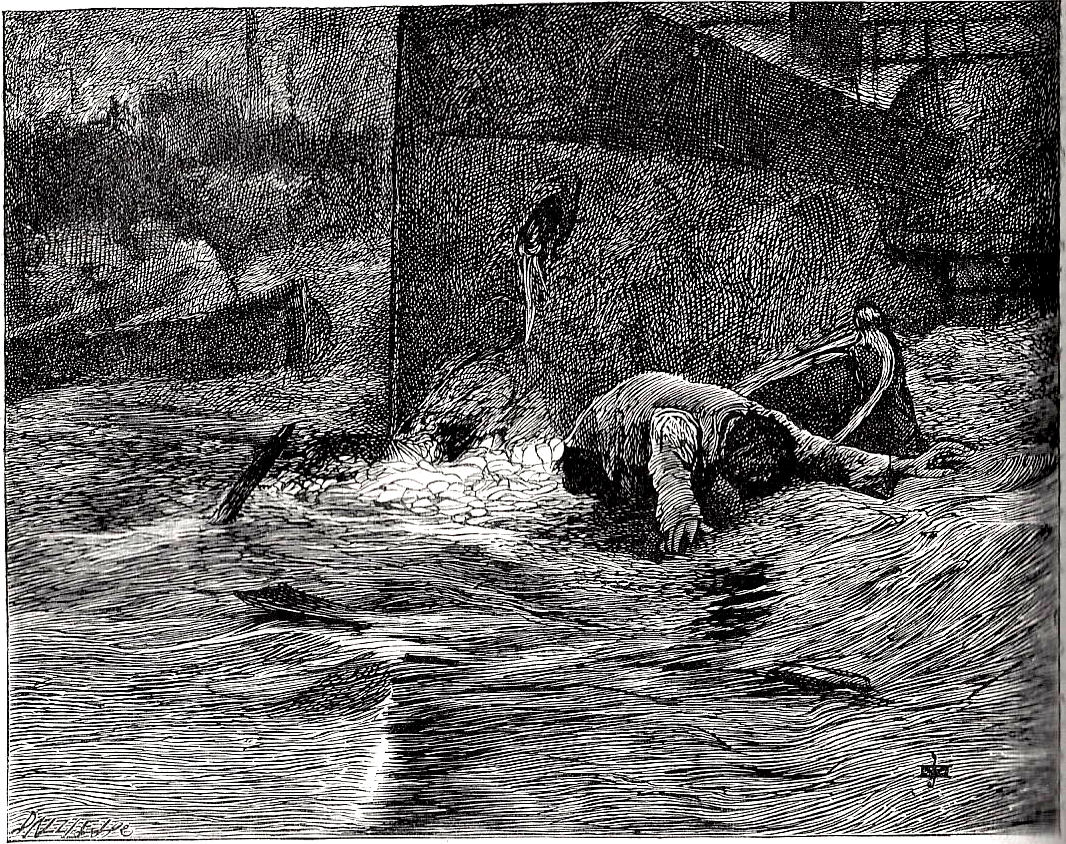

"It's summut run down in the fog." (p. 189) — James Mahoney's thirty-third illustration for Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, Household Edition (New York), 1875. Wood engraving by the Dalziels, 10.5 cm high x 13.5 cm wide. The Harper & Brothers second woodcut for secondd chapter, "A Respected Friend in a New Aspect," in the third book, "A Long Lane," realizes the scene in the bar of the Six Jolly Fellowship Porters, just after Jenny Wren has delivered Lizzie Hexam's evidence against Rogue Riderhood (and exonerating Gaffer Hexam in the murder of John Harmon) to Miss Abbey, the proprietor of the Thames-side bar. Their conversation is interrupted by the news that a steamer has just run down another waterman. The body, more dead than alive that Miss Abbey's customers pull from the river (as seen in the Mahoney illustration), proves to be none other than that of — Rogue Riderhood himself, a revelation that coincides precisely with the end of the chapter: "Why, good God! . . . that's the very man who made the declaration we have just had in our hands. That's Riderhood!" (190), the victim's identity suggested by the fur cap drifting in the water, down right, in the Mahoney illustration.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

As he stood there, doing his methodical penmanship, his ancient scribelike figure intent upon the work, and the little dolls' dressmaker sitting in her golden bower before the fire, Miss Abbey had her doubts whether she had not dreamed those two rare figures into the bar of the Six Jolly Fellowships, and might not wake with a nod next moment and find them gone.

Miss Abbey had twice made the experiment of shutting her eyes and opening them again, still finding the figures there, when, dreamlike, a confused hubbub arose in the public room. As she started up, and they all three looked at one another, it became a noise of clamouring voices and of the stir of feet; then all the windows were heard to be hastily thrown up, and shouts and cries came floating into the house from the river. A moment more, and Bob Gliddery came clattering along the passage, with the noise of all the nails in his boots condensed into every separate nail.

"What is it?" asked Miss Abbey.

"It's summut run down in the fog, ma'am," answered Bob. "There's ever so many people in the river."

"Tell 'em to put on all the kettles!" cried Miss Abbey. "See that the boiler's full. Get a bath out. Hang some blankets to the fire. Heat some stone bottles. Have your senses about you, you girls down stairs, and use 'em."

While Miss Abbey partly delivered these directions to Bob — whom she seized by the hair, and whose head she knocked against the wall, as a general injunction to vigilance and presence of mind — and partly hailed the kitchen with them — the company in the public room, jostling one another, rushed out to the causeway, and the outer noise increased.

"Come and look," said Miss Abbey to her visitors. They all three hurried to the vacated public room, and passed by one of the windows into the wooden verandah overhanging the river.

"Does anybody down there know what has happened?" demanded Miss Abbey, in her voice of authority.

"It's a steamer, Miss Abbey," cried one blurred figure in the fog.

"It always is a steamer, Miss Abbey," cried another.

"Them's her lights, Miss Abbey, wot you see a-blinking yonder," cried another.

"She's a-blowing off her steam, Miss Abbey, and that's what makes the fog and the noise worse, don't you see?" explained another.

Boats were putting off, torches were lighting up, people were rushing tumultuously to the water's edge. &mdash, Book 3, Chapter 2: "A Respected Friend in a New Aspect," p. 189-190.

Commentary

Despite the fact that it was his visual antecedent, Mahoney ten years later deviated from the choices for illustration made by Dickens and his original illustrator, Marcus Stone, so that, for the eleventh instalment in the British serialisation (March, 1865), there is no exact counterpart to this illustration of the river accident. Stone's second plate for the eleventh monthly number (Book 3, Chapters 1 — 4), Rogue Riderhood's Recovery, unfortunately let the cat out of the bag, so to speak, as it revealed to the serial reader at the very beginning of the instalment that Riderhood would, like John Harmon himself, rise again and return to life the same old reprobate, who nevertheless will experience significant changes in his life, as signalled by the loss of his fur hat. Shortly, he will abandon his vocation as a waterman to become keeper of the lock at Plashwatewr Weir. As Jane Rabb Cohen suggests,

Dickens was soon prevented by the demands on his time and dwindling energies from continuing to exercise such close supervision [of Stone as he exercised in the execution of the wrapper and the early illustrations]; yet the kind of latitude he allowed Stone in the course of Our Mutual Friend reflects neither negligence nor indifference, but rather understandable trust, partly necessitated by unavoidable absences. [205]

Readers of the Household Edition in 1875 might therefore have enjoyed a moment of suspense denied their serial counterparts in March 1865, although Mahoney's dark plate, like Stone's stage set of Miss Potterson's first-floor bedroom and his focus on the irascible Riderhood and his distressed daughter (centre), leaves something to be desired.

Although Percy Muir contends that dark plates, whether on copper, steel, or boxwood, are never wholly successful because they are striving to attain an effect that only a mezzotint can achieve, both Stone and Mahoneyuse such an illustration toconveying a sense of the horrible, near-death experience that Harmonre-lives after exiting the Riderhoods' leaving-shop.

A great deal has been made of the so-called dark plates in these books [i. e., Bleak House, Little Dorrit, and A Tale of Two Cities]. The fact is that they were neither entirely new nor entirely successful. What Browne ['Phiz'] tried to do with the dark plates was to produce the effect of mezzotinting on an etched plate. It is usually a mistake to attempt to imitate one medium in a different technique and this was no exception to the rule. The effect was produced by having a background of fine, closely spaced lines mechanically ruled all over the plates, and then, by elaborate methods of burnishing the high-lights and stopping out the shadows, to increase the contrasts. The result when seen at its best, as in 'On The Dark Road' in Dombey, is not ineffective, but at its worst, as in 'The Mourning' [sic] in Bleak House, is a rather nasty mess. [96]

Mahoney's dark plate of the resurrection of John Harmon, "Yet the cold was merciful, for it was the cold night air and the rain that restored me from a swoon" is more successful that this description of the river accident because it contains more detail and elicits the reader's sympathy for the victim of the conspiracy. Although it ertainly generates some suspense as the reader wonders who the victim is and weather he has survived the collision, the bow of the steamer, which dominates the composition, is whooly out of proportion to the drowning man and his boat, severed in two.

Rogue Riderhood in the original and later editions, 1865-1867

Left: Marcus Stone's November 1865 serial illustration of the scene at Miss Potterson's, Rogue Riderhood's Recovery. Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's dual character study of thesurly waterman and his daughter, Rogue Riderhood and Miss Pleasant at Home (1867). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

The Characters of Charles Dickens pourtrayed in a series of original watercolours by "Kyd." London, Paris, and New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, n. d.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "The Illustrators of Our Mutual Friend, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Marcus Stone, Charles Collins, Luke Fildes." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Canton: Ohio U. P., 1980. Pp. 203-228.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone [40 composite wood-block engravings]. Volume 14 of the Authentic Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901 [based on the original nineteen-month serial and the two-volume edition of 1865].

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1866. Vol. 1.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Illustrated Household Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Field; Lee and Shepard; New York: Charles T. Dillingham, 1870 [first published in The Diamond Edition, 1867].

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall' New York: Harper & Bros., 1875.

Grass, Sean. Charles Dickens's 'Our Mutual Friend': A Publishing History. Burlington, VT, and Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2014.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 21: The Other Novels." The Dickens Picture-Book. The CharlesDickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp.441-442.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. (1899). Rpt. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2004.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

Muir, Percy. Victorian Illustrated Books. London: B. T. Batsford, 1971.

"Our Mutual Friend — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Queen's University, Belfast. "Charles Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, Clarendon Edition. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, June 1864-December 1865." Accessed 12 November 2105. http://www.qub.ac.uk/our-mutual-friend/witnesses/Harpers/Harpers.htm

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 27December 2015