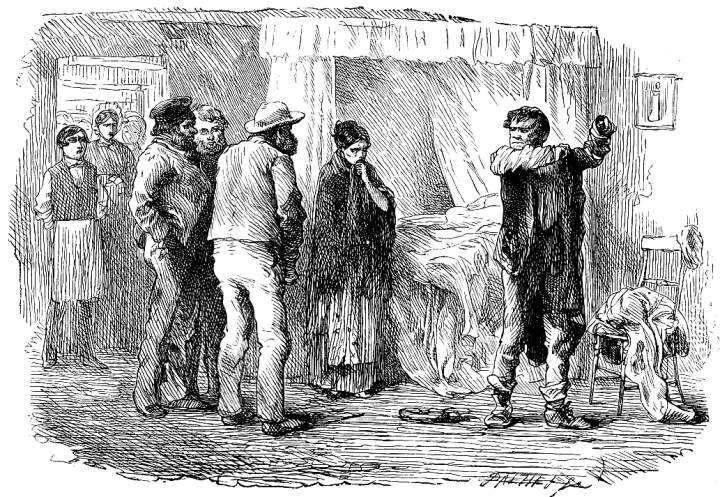

Rogue Riderhood's Recovery by Marcus Stone. Wood engraving by Dalziel. 8.8 cm high x 13 cm wide. Second illustration for the eleventh monthly number of Our Mutual Friend, Chapter Three, "The Same Respected Friend in More Aspects than One" in the third book, "A Long Lane." The Authentic edition, facing p. 388. [This part of the novel originally appeared in periodical form in March 1865.] Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. ]

The setting is Miss Abbey Potterson's riverside public-house, The Six Fellowship Porters, where the apparently lifeless body of the waterman Rogue Riderhood has been taken after a collision between his boat and steamer in the Thames. Having miraculouly been recalled to life, the surly Rogue Riderhood, just finishing dressing, is right; his daughter, Pleasant, is standing centre; and the three figures between her and Miss Potter, standing in the doorway, are Wiiliam Williams, Jonathan, and Bob Glamour. Tom Tootle, in all probability, is the other figure (the aproned waiter) standing in the doorway of the first-floor bedroom. The reader will look in vain for the attending physician, "the gentle Jew and Miss Jenny Wren" (386), to say nothing of Captain Joey. Nevertheless, the passage realized is this:

Mr. Riderhood next demands his shirt; and draws it on over his head (with his daughter's help) exactly as if he had just had a Fight.

'Warn't it a steamer?' he pauses to ask her.

'Yes, father.'

'I'll have the law on her, bust her! and make her pay for it.'

He then buttons his linen very moodily, twice or thrice stopping to examine his arms and hands, as if to see what punishment he has received in the Fight. He then doggedly demands his other garments, and slowly gets them on, with an appearance of great malevolence towards his late opponent and all the spectators. He has an impression that his nose is bleeding, and several times draws the back of his hand across it, and looks for the result, in a pugilistic manner, greatly strengthening that incongruous resemblance.

'Where's my fur cap?' he asks in a surly voice, when he has shuffled his clothes on. [389]

Rogue Riderhood, quarrelsome and obstreperous, is back. But, analsying the illustration as a whole, one is tempted to question both the moment chosen for realisation — rather than the highly dramatic passage in which "The low, bad, unimpressible face is coming up from the depths of the river" (388) and the anxious onlookers withdraw in anticipation of Riderhood's resurrection — and the effectiveness of the overall composition, which does not exploit the possibilities for contrast in terms of poses, expressions, and physical types. Surely the focus should be on the hopeful solicitousness of Pleasant and the surliness of her irrepressible parent, but Stone wastes space on describing in the vaguest possible terms Miss Potterson's first-floor bedroom. Accordingly, one is tempted to speculate about the degree of supervision provided by the author and, indeed, whether he was much involved in the process of illustration at this mid-point of composition and publication.

Dickens was soon prevented by the demands on his time and dwindling energies from continuing to exercise such close supervision [of Stone as he exercised in the execution of the wrapper and the early illustrations]; yet the kind of latitude he allowed Stone in the course of Our Mutual Friend reflects neither negligence nor indifference, but rather understandable trust, partly necessitated by unavoidable absences. His young friend was so totally dependent on the author's patronage and so free from the pressures that plagued Seymour, the vanity that tormented Cruikshank, and the competing commissions that sometimes impeded the efforts of Browne and the Christmas book artists, that Dickens must have felt he could give him certain procedural freedoms, knowing they would not be abused. Moreover, this attitude may partly reveal the author's recognition that illustrations were more ornamental than integral to Our Mutual Friend. [Cohen 205]

References

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "Marcus Stone." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1980. Pp. 203-209.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone. Volume 14 of the Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901.

Last modified 20 June 2011